| Chalcolithic Eneolithic, Aeneolithic, or Copper Age |

|---|

|

↑ Stone Age ↑ Neolithic |

|

↓ Bronze Age ↓ Iron Age |

The European Chalcolithic, the Chalcolithic (also Eneolithic, Copper Age) period of Prehistoric Europe, lasted roughly from 5000 to 2000 BC, developing from the preceding Neolithic period and followed by the Bronze Age.

It was a period of Megalithic culture, the appearance of the first significant economic stratification, and probably the earliest presence of Indo-European speakers.

The economy of the Chalcolithic, even in the regions where copper was not yet used, was no longer that of peasant communities and tribes: some materials began to be produced in specific locations and distributed to wide regions. Mining of metal and stone was particularly developed in some areas, along with the processing of those materials into valuable goods.

Ancient Chalcolithic

From c. 5000 BC to 3000 BC, copper started being used first in Southeast Europe, then in Eastern Europe, and Central Europe. From c. 3500 onwards, there was an influx of people into Eastern Europe from the Pontic-Caspian steppe (Yamnaya culture), creating a plural complex known as Sredny Stog culture. This culture replaced the Dnieper-Donets culture, and migrated northwest to the Baltic and Denmark, where they mixed with natives (TRBK A and C). This may be correlated with the spread of Indo-European languages, known as the Kurgan hypothesis. Near the end of the period, another branch left many traces in the lower Danube area (culture of Cernavodă culture I), in what seems to have been another invasion.

Meanwhile, the Danubian Lengyel culture absorbed its northern neighbours of the Czech Republic and Poland over a number of centuries, only to recede in the second half of the period. In Bulgaria and Wallachia (Southern Romania), the Boian-Marica culture evolved into a monarchy with a clearly royal cemetery near the coast of the Black Sea. This model seems to have been copied later in the Tiszan region with the culture of Bodrogkeresztur. Labour specialization, economic stratification and possibly the risk of invasion may have been the reasons behind this development. The influx of early Troy (Troy I) is clear in both the expansion of metallurgy and social organization.

In the western Danubian region (the Rhine and Seine basins) the culture of Michelsberg displaced its predecessor, Rössen. Meanwhile, in the Mediterranean basin, several cultures (most notably Chassey in SE France and La Lagozza in northern Italy) converged into a functional union, of which the most significant characteristic was the distribution network of honey-coloured flint. Despite this unity, the signs of conflicts are clear, as many skeletons show violent injuries. This was the time and area where Ötzi, a man whose well-preserved body was found in the Alps, lived. Another significant development of this period was the Megalithic phenomenon spreading to most places of the Atlantic region, bringing with it agriculture to some underdeveloped regions existing there.

Varna culture artefacts, 4500 BC

Varna culture artefacts, 4500 BC Bodrogkeresztúr gold idol, 4000-3500 BC BC

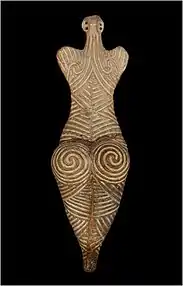

Bodrogkeresztúr gold idol, 4000-3500 BC BC Cucuteni-Trypillia figurine, 4000 BC

Cucuteni-Trypillia figurine, 4000 BC Cucuteni–Trypillia pottery

Cucuteni–Trypillia pottery Maidanetske, Ukraine, c. 3800 BC

Maidanetske, Ukraine, c. 3800 BC Copper tools, Old Europe, c. 4000 BC

Copper tools, Old Europe, c. 4000 BC Ljubljana Wheel, Slovenia, 3150 BC

Ljubljana Wheel, Slovenia, 3150 BC

Middle Chalcolithic

This period extends along the first half of the 3rd millennium BC. Most significant is the reorganization of the Danubians into the powerful Baden culture, which extended more or less to what would be the Austro-Hungarian Empire in recent times. The rest of the Balkans was profoundly restructured after the invasions of the previous period but, with the exception of the Coțofeni culture in a mountainous region, none of them show any eastern (or presumably Indo-European) traits. The new Ezero culture, in Bulgaria, had the first traits of pseudo-bronze (an alloy of copper with arsenic); as did the first significant Aegean group: the Cycladic culture after c. 2800 BC.

In the North, the supposedly Indo-European groups seemed to recede temporarily, suffering a strong cultural danubianization. In the East, the peoples of beyond the Volga (Yamnaya culture), surely eastern Indo-Europeans, ancestors of Iranians, took over southern Russia and Ukraine. In the West the only sign of unity comes from the Megalithic super-culture, which extended from southern Sweden to southern Spain, including large parts of southern Germany. But the Mediterranean and Danubian groupings of the previous period appear to have been fragmented into many smaller pieces, some of them apparently backward in technological matters.

After c. 2600 several phenomena prefigured the changes of the upcoming period. Large towns with stone walls appeared in two different areas of the Iberian Peninsula: one in the Portuguese region of Estremadura (culture of Vila Nova de São Pedro), strongly embedded in the Atlantic Megalithic culture; the other near Almería (SE Spain), centred on the large town of Los Millares, of Mediterranean character, probably affected by eastern cultural influxes (tholoi). Despite the many differences the two civilizations seemed to be in friendly contact and to have productive exchanges. According to radiocarbon dating, the Pre-Bell Beaker Chalcolithic began on the Northern Iberian Plateau in 3000 cal. BC and the Bell Beaker Chalcolithic appeared around 2500 cal. BC.[6][7][8] In the area of Dordogne (Aquitaine, France), a new unexpected culture of bowmen appeared, the culture of Artenac, which would soon take control of western and even northern France and Belgium. In Poland and nearby regions, the putative Indo-Europeans reorganized and consolidated again with the culture of the Globular Amphoras. Nevertheless, the influence of many centuries in direct contact with the still-powerful Danubian peoples had greatly modified their culture.

In the southwestern Iberian peninsula, owl-like plaques made of sandstone were discovered and dated to be crafted from 5500 to 4750 BP (Before Present). These are some of the most unique objects discovered in the Chalcolithic (copper age) cultural period. They have generally a head, two rounded eyes, and a body. Theses species were modeled after two owl species, the little owl (Athene Noctua) and the long-eared owl (Asio otux).[9]

Late Chalcolithic

This period extended from c. 2500 BC to c. 1800 or 1700 BC (depending on the region). The dates are general for the whole of Europe, and the Aegean area was already fully in the Bronze Age. c. 2500 BC the new Catacomb culture, which originated from the Yamnaya peoples in the regions north and east of the Black Sea. Some of these infiltrated Poland and may have played a significant but unclear role in the transformation of the culture of the Globular Amphorae into the new Corded Ware culture. In Britain, copper was used between the 25th and 22nd centuries BC, but some archaeologists do not recognise a British Chalcolithic because production and use was on a small scale.[10]

Around 2400 BC. this people of the Corded Ware replaced their predecessors and expanded to Danubian and Nordic areas of western Germany. One related branch invaded Denmark and southern Sweden (Single Grave culture), while the mid-Danubian basin, though showing more continuity, also displayed clear traits of new Indo-European elites (Vučedol culture). Simultaneously, in the west, the Artenac peoples reached Belgium. With the partial exception of Vučedol, the Danubian cultures, so buoyant just a few centuries ago, were wiped off the map of Europe. The rest of the period was the story of a mysterious phenomenon: the Beaker people. This group seems to have been of mercantile character and preferred being buried according to a very specific, almost invariable, ritual. Nevertheless, out of their original area of western Central Europe, they appeared only inside local cultures, so they never invaded and assimilated but rather went to live among those peoples, keeping their way of life.

The rest of the continent remained mostly unchanged and in apparent peace. From c. 2300 BC the first Beaker Pottery appeared in Bohemia and expanded in many directions, but particularly westward, along the Rhone and the sea shores, reaching the culture of Vila Nova (Portugal) and Catalonia (Spain) as its limit. Simultaneously but unrelatedly, c. 2200 BC in the Aegean region, the Cycladic culture decayed, being substituted by the new palatine phase of the Minoan culture of Crete.

The second phase of Beaker Pottery, from c. 2100 BC onwards, was marked by the displacement of the centre of this phenomenon to Portugal, inside the culture of Vila Nova. This new centre's influence reached to all southern and western France but was absent in southern and western Iberia, with the notable exception of Los Millares. After c. 1900 BC, the centre of the Beaker Pottery returned to Bohemia, while in Iberia there was a decentralization of the phenomenon, with centres in Portugal but also in Los Millares and Ciempozuelos.

See also

References

- ↑ Chapman, John (2012). "Varna". The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-19-973578-5.

- ↑ Jeunesse, Christian (2017). "From Neolithic kings to the Staffordshire hoard. Hoards and aristocratic graves in the European Neolithic: The birth of a 'Barbarian' Europe?". The Neolithic of Europe. Oxbow Books. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-78570-654-7.

- ↑ Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine Gems and Gemstones: Timeless Natural Beauty of the Mineral World, By Lance Grande

- ↑ (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/varna-bulgaria-gold-graves-social-hierarchy-prehistoric-archaelogy-smithsonian-journeys-travel-quarterly-180958733/)

- ↑ (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/oldest-gold-object-unearthed-bulgaria-180960093/)

- ↑ Marcos Saiz (2006), pp. 225–270.

- ↑ Marcos Saiz (2016), pp. 686–696.

- ↑ Marcos Saiz & Díez (2017), pp. 45–67.

- ↑ Negro, Juan J.; Blanco, Guillermo; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Eduardo; Díaz Núñez de Arenas, Víctor M. (2022-12-01). "Owl-like plaques of the Copper Age and the involvement of children". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 19227. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1219227N. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-23530-0. hdl:10272/22200. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 36456596.

- ↑ Miles, The Tale of the Axe, pp. 363, 423, n. 15

Sources

- Marcos Saiz, F. Javier (2006). La Sierra de Atapuerca y el Valle del Arlanzón. Patrones de asentamiento prehistóricos. Editorial Dossoles. Burgos, Spain. ISBN 9788496606289.

- Marcos Saiz, F. Javier (2016). La Prehistoria Reciente del entorno de la Sierra de Atapuerca (Burgos, España). British Archaeological Reports (Oxford, U.K.), BAR International Series 2798. ISBN 9781407315195.

- Marcos Saiz, F.J.; Díez, J.C. (2017). "The Holocene archaeological research around Sierra de Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain) and its projection in a GIS geospatial database". Quaternary International. 433 (A): 45–67. Bibcode:2017QuInt.433...45M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.10.002.

- Miles, David (2016). The Tale of the Axe: How the Neolithic Revolution Transformed Britain. London, UK: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05186-3.

External links

![]() Media related to Copper Age in Europe at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Copper Age in Europe at Wikimedia Commons