| Euthydemus I | |

|---|---|

| Basileus | |

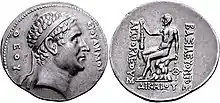

Coin of Euthydemus | |

| King of Bactria | |

| Reign | c. 224–195 BC |

| Predecessor | Diodotus II |

| Successor | Demetrius I |

| Born | c. 260 BC Ionia[1] |

| Died | 195/190 BC Bactria |

| Issue |

|

| Dynasty | Euthydemid |

Euthydemus I (Greek: Εὐθύδημος, Euthydemos) c. 260 BC – 200/195 BC) was a Greco-Bactrian king and founder of the Euthydemid dynasty. He is thought to have originally been a satrap of Sogdia, who usurped power from Diodotus II in 224 BC. Literary sources, notably Polybius, record how he and his son Demetrius resisted an invasion by the Seleucid king Antiochus III from 209 to 206 BC. Euthydemus expanded the Bactrian territory into Sogdia, constructed several fortresses, including the Derbent Wall in the Iron Gate,[2] and issued a very substantial coinage.

Biography

Euthydemus was an Ionian-Greek from one of the Magnesias in Ionia,[3] though it is uncertain from which one (Magnesia on the Maeander or Magnesia ad Sipylum), and was the father of Demetrius I, according to Strabo and Polybius.[4][5][1] William Woodthorpe Tarn proposed that Euthydemus was the son of a Greek general called Antimachus or Apollodotus, born c. 295 BC, whom he considered to be the son of Sophytes, and that he married a sister of the Greco-Bactrian king Diodotus II.[6]

War with the Seleucid Empire

Little is known of his reign until 208 BC when he was attacked by Antiochus III the Great, whom he tried in vain to resist on the shores of the river Arius (Battle of the Arius), the modern Herirud. Although he commanded 10,000 horsemen, Euthydemus initially lost a battle on the Arius [5] and had to retreat. He then successfully resisted a three-year siege in the fortified city of Bactra, before Antiochus finally decided to recognize the new ruler, and to offer one of his daughters to Euthydemus's son Demetrius around 206 BC.[5] As part of the peace treaty, Antiochus was given Indian war elephants by Euthydemus.[7]

For Euthydemus himself was a native of Magnesia, and he now, in defending himself to Teleas, said that Antiochus was not justified in attempting to deprive him of his kingdom, as he himself had never revolted against the king, but after others had revolted he had possessed himself of the throne of Bactria by destroying their descendants. (...) finally Euthydemus sent off his son Demetrius to ratify the agreement. Antiochus, on receiving the young man and judging him from his appearance, conversation, and dignity of bearing to be worthy of royal rank, in the first place promised to give him one of his daughters in marriage and next gave permission to his father to style himself king

Polybius also relates that Euthydemus negotiated peace with Antiochus III by suggesting that he deserved credit for overthrowing the descendants of the original rebel Diodotus, and that he was protecting Central Asia from nomadic invasions thanks to his defensive efforts.

The war lasted altogether three years and after the Seleucid army left, the kingdom seems to have recovered quickly from the assault. The death of Euthydemus has been roughly estimated to 200 BC or perhaps 195 BC. He was succeeded by Demetrius, who went on to invade northwestern regions of South Asia.

Activities on the Central Asian Steppe

Polybius claims that Euthydemus justified his kingship during his peace negotiations with Antiochus III in 206 BC by reference to the threat of attack by nomads on the Central Asian steppe:

- "...[he said that] if [Antiochus] did not yield to this demand, neither of them would be safe: seeing that great hoards of Nomads were close at hand, who were a danger to both; and that if they admitted them into the country, it would certainly be utterly barbarised." (Polybius, 11.34).

Archaeological evidence from coin finds shows that Euthydemus' reign saw extensive activity at fortresses in northwestern Bactria (the modern Surkhan Darya region of Uzbekistan), especially in the Gissar and Köýtendag mountains. The Seleucid fortress at Uzundara was expanded and large numbers of Euthydemus' bronze coins have been found there, as was as hundreds of arrowheads and other remains indicating a violent assault.[8] Coin finds also seem to indicate that Euthydemus was responsible for the first construction of the Derbent Wall, otherwise known as the "Iron Gate", a 1.6-1.7 km long stone wall with towers and a central fortress guarding a key pass.[9] Landislav Stančo tentatively links the archaeological evidence with the nomad threat.[10] However, Stančo also notes that Derbent wall seems to have been designed not to defend against an attack from Sogdia to the northwest, but from Bactria to the southeast. Hundreds of arrowheads also seem to indicate an attack on the wall from the southeast. Stančo proposes that Euthydemus was originally based in Sogdia and built the fortifications to protect himself from Bactria, before seizing control of the latter.[11] Lucas Christopoulos goes further, proposing that he controlled a large area going from Sogdiana to Gansu and the Tarim basin walled cities together with enrolled Hellenized Saka horsemen even before he ascended the throne of Bactria in 250-230 BC.[12]

Kuliab inscription

In an inscription found in the Kuliab area of Tajikistan, northeastern Greco-Bactria, and dated to 200-195 BC,[13] a Greek by the name of Heliodotos, dedicating an altar to Hestia, mentions Euthydemus as the greatest of all kings, and his son Demetrius I.[14]

- This fragrant altar to you, Hestia, most honoured among the gods, Heliodotus established in the grove of Zeus with its fair trees, furnishing it with libations and burnt-offerings, so that you may graciously preserve free from care, together with divine good fortune, Euthydemus, greatest of all kings and his outstanding son Demetrius, renowned for fine victories[15][16]

This is a further indication, alongside the passages from Polybius, that Euthydemus had made his son Demetrius a junior partner in his rule during his lifetime. The reference to Demetrius as a "glorious conqueror" might refer to a specific victory, in the conflict with Antiochus III[17] or in India, or look forward to future victories.[15]

Coinage

Euthydemus minted coins in gold, silver and bronze at two mints, known as 'Mint A' and 'Mint B'. He produced significantly more coins than any of his successors and was the last Greco-Bactrian coinage to include gold denominations until the time of Eucratides I (ca. 170-145 BC). Euthydemus' gold and silver issues are all minted on the Attic weight standard with a tetradrachm of ca. 16.13 g and all have the same basic design. On the obverse, his face is depicted in profile, clean-shaven, with unruly hair, and a diadem - this iconography is typical of Hellenistic kings, ultimately deriving from depictions of Alexander the Great. The reverse shows Heracles, naked, seated on a rock, resting his club on a neighbouring rock or on his knee, with a legend reading ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΕΥΘΥΔΗΜΟΥ ('of King Euthydemos').[18] Heracles was apparently a popular deity in Bactria, associated with Alexander the Great, but this reverse type is very similar to coins minted by the Seleucids in western Asia Minor, near Euthydemus' home city of Magnesia.[17][19] Heracles continues to appear on the coinage of Euthydemus' immediate successors, Demetrius and Euthydemus II.

There are four distinct versions of the obverse portrait, presumably reflecting different models given to the die engravers. The first of these is an 'idealising' portrait, depicting him as a young or middle-aged man, with very large eyes, an arching eyebrow, pointed nose and protruding chin, the diadem is very broad. The overall appearance is very similar to images of Diodotus I on his coinage.[20][21] The second shows him with a tall, large face with heavier jowls; his eye is smaller and the diadem is much narrower.[20][21] The third portrait is similar, but with the hair above his forehead stylised as a series of semicircles. Finally, in the fourth portrait style, Euthydemus is portrayed as a visibly aged man with very large jowls; his hair also interacts with the diadem in a more natural way.[20][21] Portrait type 1 is the earliest and portrait type 4 is the latest and these coins have often been interpreted as showing Euthydemus aging over the course of a long reign. However, Simon Glenn argues that the types instead represent a shift from 'idealising' portraiture to 'naturalising', pointing out that distinctions of age in the first three types are highly subjective.[21] This shift to verism represents a substantial divergence from the usual iconography of Hellenistic kings, whose coinage usually showed them in a youthful, idealised guise, regardless of their age.[18] Portrait type 4 has been compared with a Roman-period bust in the Torlonia Collection, which was accordingly identified by Jan Six (art historian) in 1894 as a bust of Euthydemus, known as the "Torlonia Euthydemus." This identification has been contested by R. R. R. Smith, who identifies the bust as a general of the Roman republic.[22]

Relative chronology

Like the earlier Diodotid coinage and that of Euthydemus' successors, monograms and die links allow the precious metal coinage to be divided into two mints, which produced coins simultaneously. "Mint A" uses two types of monogram: one in the form of vertical line bisecting an equilateral triangle, with two shorter vertical lines hanging down from the corners of the triangle, and another with an Α contained within a Π.[23] Mint B initially used three monograms, of which the most long-lasting was a combination of Ρ and Η; later these were replaced by a monogram combining a Ρ and a Κ.[24] A putative "Mint C" has now been shown to be identical with "Mint B".[25][26] Frank Holt and Brian Kritt identify "Mint B" with Bactra, the kingdom's capital. Holt identifies "Mint A" with Ai Khanoum, while Kritt prefers some other location near Ai Khanoum.[27][28] Simon Glenn emphasises the that "we do not know the location of either mint" and that it is particularly uncertain whether there was a mint at Ai Khanoum at all.[29]

The earliest coins use portrait type 1 and have a 6 o'clock die axis (i.e. the top of the obverse is aligned with the bottom of the reverse). At Mint A, these coins, Group I (A1-A10) consist of silver tetradrachms, drachms, and hemidrachms; they use either of the two monograms, plus the letters ΤΙ, ΑΝ, Α, Ν, or no monogram at all.[30] These additional letters may have referred to the specific batch of bullion used in minting the coins.[31] Partway through this issue, Mint A switches to a 12 o'clock die axis (i.e. the top of the obverse is aligned with the top of the reverse). At Mint A, Group I continues after this change.[30] At Mint B ("Group I"), the coins consist of gold staters (ca. 8.27 g), and small numbers of silver tetradrachms and drachms, and all three monograms are used.[32] Some of the gold staters are die-linked to earlier Diodotid coins minted in the name of "Antiochus," but it is possible that the linked coins are modern forgeries.[33][34] At Mint B, these coins are followed by Group II (CR1-CR3), which consists of gold staters and silver tetradrachms with portrait type 1 (but with some features similar to portrait model 3). Most of these coins use the Η with triangle monogram.[26]

The next period starts with the introduction of the second portrait type. At Mint A, Group II (A11-A14) only tetradrachms were minted in this period, all with the bisected triangle monogram, sometimes accompanied by a Ν or an Α.[35] At Mint B this issue consisted of Group III (CR4), composed of gold staters and silver tetradrachms, with a monogram composed of Ρ, Η, and Α. This is followed by the first issue at Mint B to use a 12 o'clock die axis, Group IV (B13), consisting only of tetradrachms, all with the ΡΚ monogram, and produced in much large numbers than had previously been the case at Mint B.[36] The third portrait type, introduced only at Mint B, characterises Group V (B14-B15), which consists of tetradrachms and drachms.

At Mint A, the introduction of portrait type 4 is marked by the start of Group III (A16-A17) and a gold octodrachm (A15) with a reverse modelled on Mint B's Group V, known from a single example weighing 32.73 g. This issue is generally associated with the end of Antiochus III's siege of Bactra in 206 BC.[37][38][39] Group III is much smaller than previous issues at Mint A and is the last issue produced by the mint in Euthydemus' reign.[40] At Mint B, the introduction of portrait 4 coincides with the large issue of Groups VI and VII (B17).[41]

Bronze coinage

In addition to the precious metal coinage, Euthydemus also produced bronze coins. Almost all have a bearded male head, identified as Heracles, on the obverse and a rearing horse on the reverse with the legend ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΕΥΘΥΔΗΜΟΥ ('of King Euthydemos'). The earlier coins have thick flans with beveled edges (like the bronze of the Diodotids) and no monograms. These coins were issued in four denominations, referred to by modern scholars as a double unit (5.26-11.82 g), a single unit (2.95-5.07 g), a half unit (1.47-2.28 g), and a quarter unit (0.76-0.79 g). Some of the quarter units have a horse's head or a trident on the reverse instead of the usual reverse type.[42] Apparently later issues have thinner, flat flans. These bronzes were minted in the double, single, and half denominations. Most of them have no monograms, but some of them bear the ΡΚ symbol associated with Groups IV-VII at Mint B, and a few have a trident, anchor with ΔΙ, or an Ε.[43] The anchor was one of the main symbols of the Seleucid dynasty and ΔΙ is a monogram used by the Seleucids, so Holt interpreted it as commemorating Euthydemus' treaty with Antiochus III in 206 BC.[27] Simon Glenn is sceptical of this argument, seeing the anchor and other symbols as control marks, but he entertains the possibility that the anchor indicates "a shared production process" between the anchor bronzes and the coinage produced by Antiochus III in Bactria.[43]

Posthumous coinage

Euthydemus is also featured on the 'pedigree' coinage produced by the later kings Agathocles and Antimachus I. On this coinage he bears the royal epithet, Theos ('God'); it is unclear whether he used this title in life or if it was assigned to him by Agathocles.[44] His coins were imitated by the nomadic tribes of Central Asia for decades after his death; these imitations are called "barbaric" because of their crude style. Lyonnet proposes that these coins were produced by refugees fleeing the destruction of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom by the Yuezhi in the mid-second century BC.[45]

Torlonia Euthydemus

_-_51285704332.jpg.webp)

The "Torlonia Euthydemus" or "Albani Euthydemus" bust, now in the Torlonia Collection in Rome but formerly belonging to the Villa Albani collection, has often been suggested as a possible statue of the Bactrian ruler Euthydemus, based on resemblance with his effigy on coinage.[46][47] This is now rejected, as the statue in question is now considered as a 1st century portrait of a Republican commander or a client ruler.[47][48] The style of the statue itself is consistent with the style of the Republican period, rather than the Hellenistic period.[46] The style of the broad-brimmed hat on the statue is also very different from the Hellenistic kausia.[46]

References

- 1 2 Glenn 2020, pp. 6, 41–42.

- ↑ Stančo 2021, p. 262-265.

- ↑ Tarn, William Woodthorpe (2010-06-24). The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-108-00941-6.

- ↑ Strabo, Geography 11.11.1

- 1 2 3 Polybius 11.34 Siege of Bactra

- ↑ Tarn, William Woodthorpe (2010-06-24). The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 9781108009416.

- ↑ Polybius. Histories.

adding to his own the elephants belonging to Euthydemus.

- ↑ Stančo 2021, p. 262-264.

- ↑ Stančo 2021, p. 264-265.

- ↑ Stančo 2021, p. 262.

- ↑ Stančo 2021, p. 265-266.

- ↑ Lucas, Christopoulos; Dionysian rituals and the Golden Zeus of China http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp326_dionysian_rituals_china.pdf pp.75-118

- ↑ Wallace 2016, p. 206.

- ↑ Bopearachchi 2007, p. 48.

- 1 2 Glenn 2020, p. 8.

- ↑ Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum: 54.1569

- 1 2 Bopearachchi 2011, p. 47.

- 1 2 Glenn 2020, pp. 32–34.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, pp. 41–42.

- 1 2 3 Kritt 2001, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 4 Glenn 2020, pp. 32–34, 71–72.

- ↑ Smith 1988, Appendix 4.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, pp. 72–75.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, pp. 76–80.

- ↑ Kritt 2015, p. 56.

- 1 2 Glenn 2020, p. 78.

- 1 2 Holt 1999, p. 132.

- ↑ Kritt 2001, pp. 66, 135.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, pp. 80–81.

- 1 2 Glenn 2020, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, p. 74.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, pp. 76–78.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, p. 76.

- ↑ These may be coins of Diodotus I in the name of the Seleucid king Antiochus II Theos or coins of a putative successor of Diodotus II called Antiochus Nicator Glenn 2020, p. 76.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, p. 79.

- ↑ Holt 1999, p. 131.

- ↑ Kritt 2001.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, p. 75.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, pp. 73 & 75.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, p. 80.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, pp. 81–82.

- 1 2 Glenn 2020, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Glenn 2020, pp. 137 & 156-158.

- ↑ Lyonnet 2021, pp. 324–326.

- 1 2 3 Bopearachchi, Osmund (1998). "A Faience Head of a Graeco-Bactrian King from Ai Khanum". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 12: 27. ISSN 0890-4464. JSTOR 24049090.

- 1 2 Lerner 1999, p. 53.

- ↑ Bivar, A.D.H. "EUTHYDEMUS in the Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org.

Bibliography

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (2007). "Some Observations on the Chronology of the Early Kushans". In Gyselen, R. (ed.). Des Indo-Grecs aux Sassanides: données pour L'histoire et la géographie historique [From the Indo-Greeks to the Sassanids: Data for History and Historical Geography] (in French). Leuven: Peeters. pp. 41–53. ISBN 9782952137614.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (2011). "The Emergence of the Greco-Baktrian and Indo-Greek Kingdoms". In Wright, Nicholas L. (ed.). Coins from Asia Minor and the East: Selections from the Colin E. Pitchfork Collection. Adelaide: Numismatic Association of Australia. pp. 47–51. ISBN 978-0-646-55051-0.

- Bordeaux, Olivier (2021). "Monetary Policies during the early Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom (250-190 BCE)". In Mairs, Rachel (ed.). The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek world. Routledge worlds, vol. 15. Abingdon, Oxon & New York. pp. 510–519. doi:10.4324/9781315108513. ISBN 9781138090699. S2CID 226338994.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Glenn, Simon (2020). Money and Power in Hellenistic Bactria: Euthydemus I to Antimachus I. New York: American Numismatic Society. ISBN 978-0897223614.

- Holt, Frank L. (1981). "The Euthydemid coinage of Bactria: further hoard evidence from Ai-Khanoum". Revue numismatique. 6 (23): 7–44. doi:10.3406/numi.1981.1811.

- Holt, Frank L. (1999). Thundering Zeus: The Making of Hellenistic Bactria. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0520211405.

- Kritt, Brian (2001). Dynastic transitions in the coinage of Bactria: Antiochus-Diodotus-Euthydemus. London: Classical Numismatic Group. ISBN 9780963673879.

- Kritt, Brian (2015). New Discoveries in Bactrian Numismatics. Lancaster, PA: Classical Numismatics Group. ISBN 9780989825481.

- Lerner, Jeffrey D. (1999). The Impact of Seleucid Decline on the Eastern Iranian Plateau: The Foundations of Arsacid Parthia and Graeco-Bactria. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-07417-9.

- Lyonnet, Bertille (2021). "Sogdia". In Mairs, Rachel (ed.). The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek World. Routledge worlds, vol. 15. Abingdon, Oxon & New York: Routledge. pp. 313–327. doi:10.4324/9781315108513. ISBN 978-1138090699. S2CID 226338994.

- Smith, R. R. R. (1988). Hellenistic Royal Portraits. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198132240.

- Stančo, Ladislav (2021). "Southern Uzbekistan". In Mairs, Rachel (ed.). The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek World. Routledge worlds, vol. 15. Abingdon, Oxon & New York: Routledge. pp. 249–285. doi:10.4324/9781315108513. ISBN 978-1138090699. S2CID 226338994.

- Wallace, Shane (2016). "Greek Culture in Afghanistan and India: Old Evidence and New Discoveries". Greece & Rome. 63 (2): 205–226. doi:10.1017/S0017383516000073. S2CID 163916645.

External links

- Coins of Euthydemus

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.