Exploration is the process of exploring, an activity which has some expectation of discovery. Organised exploration is largely a human activity, but exploratory activity is common to most organisms capable of directed locomotion and the ability to learn, and has been described in, amongst others, social insects foraging behaviour, where feedback from returning individuals affects the activity of other members of the group.[1]

Exploration has been defined as:

- To travel somewhere in search of discovery.[2]

- To examine or investigate something systematically.[2]

- To examine diagnostically.[2]

- To (seek) experience first hand.[2]

- To wander without any particular aim or purpose.[2]

In all these definitions there is an implication of novelty, or unfamiliarity or the expectation of discovery in the exploration, whereas a survey implies directed examination, but not necessarily discovery of any previously unknown or unexpected information. The activities are not mutually exclusive, and often occur simultaneously to a variable extent. The same field of investigation or region may be explored at different times by different explorers with different motivations, who may make similar or different discoveries.

Intrinsic exploration involves activity that is not directed towards a specific goal other than the activity itself.[3]

Extrinsic exploration has the same meaning as appetitive behavior.[4] It is directed towards a specific goal.

Motivation

Curiosity is a quality related to inquisitive thinking and activities such as exploration, investigation, and learning, evident by observation in humans and other animals.[5][6] Curiosity has been found to be a strong motivation for exploration. When the potential external rewards are uncertain or unclear, an intrinsic drive is more likely to motivate exploration sufficiently to achieve results. Factors suggested to underlie curiosity include gain of information, utility of the information, perceived progress, and novelty.[7] Exploratory behavior is the movements of people and other animals while becoming familiar with new environments, even when there is no obvious biological advantage to it. A lack of exploratory behaviour may be considered an indication of fearfulness or emotionality.[8]

- Inspective exploration or specific exploration is directed towards reducing uncertainty, reducing anxiety, or fear, associated with novel stimuli, and thus decreasing arousal.[9]

- Diversive exploration is exploratory behavior seeking seeking novel or otherwise activating stimuli and thus increasing arousal.[10]

- Affective exploration is behaviour directed towards maintaining a desired hedonic level of stimulation.[11]

Types

Travelling in search of discovery

Travelling with the expectation of discovery is often motivated by a combinion of aspects of inspective and diversive exploration. There are three major subdivisions of this class of exploration, based on the technology involved.

Geographical

Geographical exploration, sometimes considered the default meaning for the more general term exploration, is the practice of discovering lands and regions of the planet Earth remote or relatively inaccessible from the origin of the explorer.[12] The surface of the Earth not covered by water has been relatively comprehensively explored, as access is generally relatively straightforward, but underwater and subterranean areas are far less known, and even at the surface, much is still to be discovered in detail in the more remote and inaccessible wilderness areas.

Two major eras of geographical exploration occurred in human history: The first, covering most of Human history, saw people moving out of Africa, settling in new lands, and developing distinct cultures in relative isolation.[13] Early explorers settled in Europe and Asia; about 14,000 years ago, some crossed the Ice Age land bridge from Siberia to Alaska, and moved southwards to settle in the Americas.[12] For the most part, these cultures were ignorant of each other's existence.[13] The second period of exploration, occurring over the last 10,000 years, saw increased cross-cultural exchange through trade and exploration, and marked a new era of cultural intermingling, and more recently, convergence.[13]

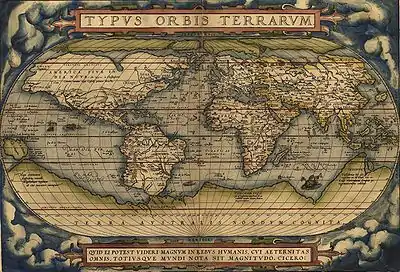

Early writings about exploration date back to the 4th millennium B.C. in ancient Egypt. One of the earliest and most impactful thinkers on exploration was Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD. Between the 5th century and 15th century AD, most exploration was done by Chinese and Arab explorers. This was followed by the Age of Discovery after European scholars rediscovered the works of early Latin and Greek geographers. While the Age of Discovery was partly driven by land routes outside of Europe becoming unsafe,[14] and a desire for conquest, the 17th century also saw exploration driven by nobler motives, including scientific discovery and the expansion of knowledge about the world.[12] This broader knowledge of the world's geography meant that people were able to make world maps, depicting all land known. The first modern atlas was the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, published by Abraham Ortelius, which included a world map that depicted all of Earth's continents.[15]: 32

Underwater

Underwater exploration is the exploration of any underwater environment, either by direct observation by the explorer, or by remote observation and measurement under the direction of the investigators. Systematic, targeted exploration, with simultaneous survey, and recording of data, followed by data processing, interpretation and publication, is the most effective method to increase understanding of the ocean and other underwater regions, so they can be effectively managed, conserved, regulated, and their resources discovered, accessed, and used. Less than 10% of the ocean has been mapped in any detail, even less has been visually observed, and the total diversity of life and distribution of populations is similarly incompletely known.[16]

Space

.jpg.webp)

Space exploration is the use of astronomy and space technology to explore outer space.[17] While the exploration of space is currently carried out mainly by astronomers with telescopes, its physical exploration is conducted both by uncrewed robotic space probes and human spaceflight. Space exploration, like its classical form astronomy, is one of the main sources for space science.

While the observation of objects in space, known as astronomy, predates reliable recorded history, it was the development of large and relatively efficient rockets during the mid-twentieth century that allowed physical extraterrestrial exploration to become a reality. Common rationales for exploring space include advancing scientific research, national prestige, uniting different nations, ensuring the future survival of humanity, and developing military and strategic advantages against other countries.[18]

Systematic examination or investigation

Systematic investigation is done in an orderly and organised manner, generally following a plan, though it should be a flexible plan, which is amenable to rational adaptation to suit circumstances, as the concept of exploration accepts the possibility of the unexpected being encountered, and the plan must survive such encounters to remain useful.

Science is a rigorous, systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the world.[19][20] Modern science is typically divided into three major branches:[21] natural sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, and biology), which study the physical world; the social sciences (e.g., economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and societies;[22][23] and the formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and theoretical computer science), which study formal systems, governed by axioms and rules.[24][25] There is disagreement whether the formal sciences are science disciplines,[26][27][28] because they do not rely on empirical evidence.[29][27] Applied sciences are disciplines that use scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as in engineering and medicine.[30][31][32]

Prospecting for minerals is an example of systematic investigation and of inspective exploration. Traditionally prospecting relied on direct observation of mineralisation in rock outcrops or in sediments, but more recently also includes the use of geologic, geophysical, and geochemical tools to search for anomalies which can narrow the search area. The area to be prospected should be covered sufficiently to minimise the risk of missing something important, but can take into account previous experience that certain geological evidence correlates with a very low probability of finding the desired minerals, and other evidence indicates a high probability, making it efficient to concentrate on the areas of high probability when they are found, and to skip areas of very low probability. Once an anomaly has been identified and interpreted to be a prospect, more detailed exploration of the potential reserve can be done by soil sampling, drilling, seismic surveys, and similar methods to assess the most appropriate method and type of mining and the economic potential.[33]

Diagnostical examination

Diagnosis is the identification of the nature and cause of a given phenomenon. Diagnosis is used in many different disciplines, such as medicine, forensic science and engineering failure analysis, with variations in the use of logic, analytics, and experience, to determine causality.[34] A diagnostic examination explores the available evidence to try to identify likely causes for observed effects, and may also investigate further with the intention to discover additional relevant evidence. This is an instance of inspective and extrinsic exploration.

To seek experience first hand

Exploration as the pursuit of first hand experience and knowledge is often an example of diversive and intrinsic exploration when done for personal satisfaction and entertainment, though it may also be for purposes of learning or verifying the information provided by others, which is an extrinsic motivation, and which is likely to be characterised by a relatively systematic approach. As the personal aspect of the experience is central to this type of exploration, the same region or range of experiences may be explored repeatedly by different people, for each can have a reasonable expectation of personal discovery.

Wandering without any particular aim or purpose

Wandering about in the hope or expectation of serendipitous discovery may also be considered a form of diversive exploration. This form of exploration may be done in a physical or information environment, such as exploring the internet, also known as web surfing.[35]

Other animals

Exploratory behavior has been defined as behavior directed toward getting information about the environment,[36] or to locate things such as food or individuals. Exploration usually follows a sequence, in which four stages can be identified.[37] The first phase is search, in which the subject moves around to contact relevant stimuli, to which the subject pays attention, and may approach and investigate. The sequence may be interrupted by flight if danger is recognised, or a return to search if the stimulus is not interesting or useful.[38][39][40][41]

A tendency to explore a new environment has been recognised in a wide range of free-moving animals from invertebrates to primates. Various forms of exploratory behaviour in animas have been analysed and categorised since 1960.[3]

See also

- Exploration geophysics – Applied branch of geophysics and economic geology

- Exploration problem – Use of a robot to maximize the knowledge over a particular area

- Intrinsic motivation (artificial intelligence) – Mechanism for enabling artificial agents to exhibit curiosity

- Motivation – Inner state causing goal-directed behavior

- Overlanding – Travel to remote places focused on the journey more than destination

- Simultaneous localization and mapping – Computational navigational technique used by robots and autonomous vehicles

- United States Exploring Expedition – An American exploring and surveying expedition, 1838 to 1842

Explorers:

References

- ↑ Biesmeijer, J.; de Vries, H. (2001). "Exploration and exploitation of food sources by social insect colonies: a revision of the scout-recruit concept". Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 49 (2–3): 89–99. doi:10.1007/s002650000289. hdl:1874/1185. S2CID 37901620.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wiktionary contributors (30 November 2022). "explore". Wiktionary, The Free Dictionary. Archived from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- 1 2 Hughes, Robert N (December 1997). "Intrinsic exploration in animals: motives and measurement". Behavioural Processes. 41 (3): 213–226. doi:10.1016/S0376-6357(97)00055-7. PMID 24896854. S2CID 23321360. Archived from the original on 2023-01-24. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ↑ Wood-Gush, D.G.M.; Vestergaard, K. (1989). "Exploratory behavior and the welfare of intensively kept animals". Journal of Agricultural Ethics. 2 (2): 161–169. doi:10.1007/BF01826929. S2CID 144112548.

- ↑ Berlyne DE. (1954). "A theory of human curiosity". Br J Psychol. 45 (3): 180–91. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1954.tb01243.x. PMID 13190171.

- ↑ Berlyne DE. (1955). "The arousal and satiation of perceptual curiosity in the rat". J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 48 (4): 238–246. doi:10.1037/h0042968. PMID 13252149.

- ↑ Poli, F.; Meyer., M.; Mars., R.B.; Hunnius, S. (August 2022). "Contributions of expected learning progress and perceptual novelty to curiosity-driven exploration". Cognition. 225: 105119. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2022.105119. PMC 9194910. PMID 35421742.

- ↑ "exploratory behavior". APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ↑ "inspective exploration". APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

defined by Daniel E. Berlyne

- ↑ "diversive exploration". APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association. Archived from the original on 26 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

defined by Daniel E. Berlyne

- ↑ Piccone, Jason (Spring 1999). "Curiosity and Exploration". www.csun.edu. California State University, Northridge. Archived from the original on 26 January 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

Wohlwill (1981)

- 1 2 3 Royal Geographical Society (2008). Atlas of Exploration. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534318-2. Archived from the original on October 16, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2022 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (October 17, 2007). Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-24247-8. Archived from the original on October 16, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "European exploration - The Age of Discovery | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2022-10-06. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ↑ "Chapter 2 - Brief History of Land Use—" (PDF). Global Land Outlook (Report). United Nations Convention on Desertification. 2017. ISBN 978-92-95110-48-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 15, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ↑ "How much of the ocean have we explored?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ↑ "How Space is Explored". NASA. Archived from the original on 2009-07-02.

- ↑ Roston, Michael (28 August 2015). "NASA's Next Horizon in Space". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 August 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ Wilson, E.O. (1999). "The natural sciences". Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (Reprint ed.). New York: Vintage. pp. 49–71. ISBN 978-0-679-76867-8.

- ↑ Heilbron, J.L.; et al. (2003). "Preface". The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. vii–x. ISBN 978-0-19-511229-0.

...modern science is a discovery as well as an invention. It was a discovery that nature generally acts regularly enough to be described by laws and even by mathematics; and required invention to devise the techniques, abstractions, apparatus, and organization for exhibiting the regularities and securing their law-like descriptions.

- ↑ Cohen, Eliel (2021). "The boundary lens: theorising academic actitity". The University and its Boundaries: Thriving or Surviving in the 21st Century. New York: Routledge. pp. 14–41. ISBN 978-0-367-56298-4. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ↑ Colander, David C.; Hunt, Elgin F. (2019). "Social science and its methods". Social Science: An Introduction to the Study of Society (17th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 1–22.

- ↑ Nisbet, Robert A.; Greenfeld, Liah (October 16, 2020). "Social Science". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on February 2, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ↑ Löwe, Benedikt (2002). "The formal sciences: their scope, their foundations, and their unity". Synthese. 133 (1/2): 5–11. doi:10.1023/A:1020887832028. S2CID 9272212.

- ↑ Rucker, Rudy (2019). "Robots and souls". Infinity and the Mind: The Science and Philosophy of the Infinite (Reprint ed.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 157–188. ISBN 978-0-691-19138-6. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ↑ Bishop, Alan (1991). "Environmental activities and mathematical culture". Mathematical Enculturation: A Cultural Perspective on Mathematics Education. Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 20–59. ISBN 978-0-7923-1270-3. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- 1 2 Nickles, Thomas (2013). "The Problem of Demarcation". Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 104.

- ↑ Bunge, Mario (1998). "The Scientific Approach". Philosophy of Science. Vol. 1, From Problem to Theory (revised ed.). New York: Routledge. pp. 3–50. ISBN 978-0-7658-0413-6.

- ↑ Fetzer, James H. (2013). "Computer reliability and public policy: Limits of knowledge of computer-based systems". Computers and Cognition: Why Minds are not Machines. Newcastle, United Kingdom: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 271–308. ISBN 978-1-4438-1946-6.

- ↑ Fischer, M.R.; Fabry, G (2014). "Thinking and acting scientifically: Indispensable basis of medical education". GMS Zeitschrift für Medizinische Ausbildung. 31 (2): Doc24. doi:10.3205/zma000916. PMC 4027809. PMID 24872859.

- ↑ Sinclair, Marius (1993). "On the Differences between the Engineering and Scientific Methods". The International Journal of Engineering Education. Archived from the original on November 15, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- ↑ Bunge, M (1966). "Technology as Applied Science". In Rapp, F. (ed.). Contributions to a Philosophy of Technology. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. pp. 19–39. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-2182-1_2. ISBN 978-94-010-2184-5. S2CID 110332727.

- ↑ "Mining - Prospecting and exploration". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ↑ "A Guide to Fault Detection and Diagnosis". gregstanleyandassociates.com. Archived from the original on 2019-09-17. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ↑ Muylle, Steve; Moenaert, Rudy; Despontin, Marc (1999). "A grounded theory of World Wide Web search behaviour". Journal of Marketing Communications. 5 (3): 143–155. doi:10.1080/135272699345644.

- ↑ Meyer, Jerrold S. (1998). "22 - Behavioral Assessment in Developmental Neurotoxicology: Approaches Involving Unconditioned Behaviors Pharmacologic Challenges in Rodents". Handbook of Developmental Neurotoxicology. pp. 403–426. doi:10.1016/B978-012648860-9.50029-7.

- ↑ "Exploration". mousebehavior.org. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ↑ "Search". mousebehavior.org. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ↑ "Investigate". mousebehavior.org. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ↑ "Attend". mousebehavior.org. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ↑ "Approach". mousebehavior.org. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

Further reading

General

- Baker, J. N. L. A History of Geographical Discovery and Exploration. Rev. ed. New York: Cooper Square Publishers, 1967.

- Beaglehole, J. C. The Exploration of the Pacific. 3rd ed. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1966.

- Boorstin, Daniel. The Discoverers. New York: Random House, 1983.

- Brown, Lloyd A. The Story of Maps. New York: Dover Publications, 1979.

- Bitterli, Urs. Cultures in Conflict: Encounters Between European and Non-European Cultures, 1492–1800. Translated by Ritchie Robertson. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1989.

- Buisseret, David, ed. The Oxford Companion to World Exploration. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Cannon, Michael. The Exploration of Australia. Sydney: Reader’s Digest Services, 1987.

- Crosby, Alfred W. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Social Consequences of 1492. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1972.

- Crosby, Alfred W. Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe. 1492: The Year the World Began. New York: HarperOne, 2009.

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe. Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. New York: Norton, 2006.

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe, ed. The Times Atlas of World Exploration: 3,000 Years of Exploring, Explorers, and Mapmaking. New York: Times Books, 1991.

- Fernlund, Kevin Jon. A Big History of North America, from Montezuma to Monroe. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2022.

- Goetzmann, William H. New Lands, New Men: America and the Second Great Age of Discovery. New York: Viking Press, 1986.

- Goetzmann, William H. and Glyndwr Williams. The Atlas of North American Exploration: From the Norse Voyages to the Race to the Pole. New York: Prentice Hall, 1992.

- Hall, D. H. History of the Earth Sciences During the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions, with Special Emphasis on the Physical Geosciences. Amsterdam: Elsevier Scientific Publishing, 1976.

- von Hagen, Victor Wolfgang. South America Called Them: Explorations of the Great Naturalists: La Condamine, Humboldt, Darwin, Spruce. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1945.

- Hakluyt Society, Series I and II. Some 290 volumes of original accounts in English translation. See also its periodical, Journal of the Hakluyt Society.

- Mann, Charles C. 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011.

- McNeill, William. Plagues and Peoples. New York: Knopf Doubleday, 1977.

- Mountfield, David. A History of African Exploration. Northbrook, IL: Domus Books, 1976.

- Mountfield, David. A History of Polar Exploration. New York: Dial Press, 1974.

- Oxford University Press. Oxford Atlas of Exploration. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Parry, J. H. The Age of Reconnaissance: Discovery, Exploration and Settlement 1450–1650. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963.

- Parry, J. H. The Discovery of South America. New York: Taplinger, 1979.

- Pyne, Stephen J. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned About a Wider World. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2021.

- Reader’s Digest. Antarctica: Great Stories from the Frozen Continent. Surrey Hills, NSW: Reader’s Digest Services, 1985.

- Richards, John F. The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Pre-Renaissance

- Sauer, Carl O. Northern Mists. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968.

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe. Before Columbus: Exploration and Colonisation from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, 1229–1492. London: Macmillan Education, 1987.

- Jones, Gwyn. The Norse Atlantic Saga. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Scammell, G. V. The World Encompassed: The First European Maritime Empires c. 800–1650. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981.

Exploration and Empire

- Aldrich, Robert. Greater France: A History of French Oversea Expansion. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

- Bleichmar, Daniela, ed., Science in the Spanish and Portuguese Empires, 1500–1800. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009.

- Boxer, C. R. The Dutch Seaborne Empire 1600–1800. New York: Viking Penguin, 1965.

- Boxer, C. R. The Portuguese Seaborne Empire 1415–1825. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975.

- Crowley, Roger. City of Fortune: How Venice Ruled the Seas. New York: Random House, 2013.

- Cuyvers, Luc. Into the Rising Sun: Vasco da Gama and the Search for the Sea Route to the East. New York: TV Books, 1999.

- DeVoto, Bernard. The Course of Empire. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1952.

- Diffie, Bailey W., and George D. Winius. Foundations of the Portuguese Empire 1415–1580. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977.

- Dreyer, Edward L. Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433. New York: Pearson Longman, 2007.

- Elliott, J. H. Imperial Spain 1469–1716. London: Penguin, 1963.

- Engstrand, Iris H. W. Spanish Scientists in the New World: The Eighteenth-Century Expeditions. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981.

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe. The Canary Islands After the Conquest: The Making of a Colonial Society in the Early Sixteenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982.

- Goetzmann, William H. Exploration and Empire: The Explorer and the Scientist in the Winning of the American West. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. (1967).

- Grove, Richard H. Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens, and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600–1860. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Jane, Cecil Jane, trans. and ed., The Four Voyages of Columbus. New York: Dover Publications, 1988.

- Leonard, Irving A. Books of the Brave: Being an Account of Books and of Men in the Spanish Conquest and Settlement of the Sixteenth-Century New World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

- Lloyd, T. O. The British Empire, 1558–1983. New York: Oxford University Press, 1984.

- Lewis, Bernard. The Muslim Discovery of Europe. New York: W. W. Norton, 2001.

- Moorehead, Alan. The Fatal Impact: The Invasion of the South Pacific 1767–1840. New York: Harper and Row, 1987.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages, A.D. 500–1600. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. The European Discovery of America: The Southern Voyages, 1492–1616. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Great Explorers: The European Discovery of America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

- Newitt, Malyn. A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400–1668. New York: Routledge, 2005.

- Parry, J. H. The Establishment of the European Hegemony 1415–1715: Trade and Exploration in the Age of the Renaissance. 3rd ed., rev. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1966.

- Parry, J. H. The Spanish Seaborne Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- Penrose, Boies. Travel and Discovery in the Renaissance 1420–1640. New York: Atheneum, 1975.

- Sauer, Carl O. The Early Spanish Main. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966.

- Sauer, Carl O. Seventeenth Century North America. Berkeley: Turtle Island, 1980.

- Sauer, Carl O. Sixteenth Century North America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971.

The Continents

- Alexander von Humboldt. Netzwerke des Wissens. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 1999.

- Bartlett, Richard W. Great Surveys of the American West. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980.

- Becker, Peter. The Pathfinders: The Saga of Exploration in Southern Africa. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1985.

- Bitterli, Urs. Cultures in Conflict: Encounters Between European and Non-European Cultures, 1492–1800. Translated by Ritchie Robertson. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1989.

- Blainey, Geoffrey. A Land Half Won. South Melbourne: Macmillan Company of Australia, 1980.

- Blunt, Wilfred. Linnaeus: The Compleat Naturalist. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Botting, Douglas. Humboldt and the Cosmos. New York: Harper and Row, 1973.

- Bough, Barry M. First Across the Continent: Sir Alexander Mackenzie. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

- Cannon, Michael. The Exploration of Australia. Sydney: Reader’s Digest Services, 1987.

- de Terra, Helmut. Humboldt: The Life and Times of Alexander von Humboldt, 1769–1859. New York: Octagon Books, 1979.

- DeVoto, Bernard. The Journals of Lewis and Clark. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1953.

- Fernlund, Kevin J. William Henry Holmes and the Rediscovery of the American West. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 2000.

- Ferreiro, Larrie D. Measure of the Earth: The Enlightenment Expedition That Reshaped Our World. New York: Basic Books, 2011.

- Ford, Corey. Where the Sea Breaks its Back: The Epic Story of Early Naturalist Georg Steller and the Russian Exploration of Alaska. Boston: Little, Brown, 1966.

- Goetzmann, William H. Army Exploration in the American West, 1803-1863. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959.

- Goetzmann, William H. "The Role of Discovery in American History," in American Civilization, ed. Daniel J. Boorstin. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1972.

- Jeal, Tim. Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa’s Greatest Explorer. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2007.

- McIntyre, Kenneth Gordon. The Secret Discovery of Australia: Portuguese Ventures 250 Years Before Captain Cook. Sydney: Picador, 1977.

- Pyne, Stephen J. Grove Karl Gilbert: A Great Engine of Research. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2007.

- Pyne, Stephen J. How the Canyon Became Grand: A Short History. New York: Viking, 1998.

- Rayfield, Donald. The Dream of Lhasa: The Life of Nikolay Przhevalsky (1839–88), Explorer of Central Asia. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1976.

- Ronda, James. Finding the West: Explorations with Lewis and Clark. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 2001.

- Ross, John F. The Promise of the Grand Canyon: John Wesley Powell's Perilous Journey and His Vision for the American West. New York: Viking, 2018.

- Schullery, Paul, ed. The Grand Canyon: Early Impressions. Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press, 1981.

- Stegner, Wallace. Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West. Boston: Houghton Mifflin and Company, 1953.

- Vigil, Ralph H. "Spanish Exploration and the Great Plains in the Age of Discovery: Myth and Reality." Great Plains Quarterly 10, no. 1 (1990): 3–17.

- Weber, David J. Richard H. Kern: Expeditionary Artist in the Far Southwest, 1848-1853. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum, 1985.

The Oceans

- Ballard, Robert, with Will Hively. The Eternal Darkness: A Personal History of Deep-Sea Exploration. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Corfield, Richard. The Silent Landscape: The Scientific Voyage of HMS Challenger. Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press, 2003.

- Hamblin, Jacob Darwin. Oceanographers and the Cold War: Disciples of Marine Science. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005.

- Hannigan, John. The Geopolitics of Deep Oceans. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016.

- Hellwarth, Ben. SEALAB: America’s Forgotten Quest to Live and Work on the Ocean Floor. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012.

- Hsü, Kenneth J. The Mediterranean Was a Desert: A Voyage of the Glomar Challenger. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Koslow, Tony. The Silent Deep: The Discovery, Ecology and Conservation of the Deep Sea. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

- Kroll, Gary. America’s Ocean Wilderness: A Cultural History of Twentieth-Century Exploration. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008.

- Linklater, Eric. The Voyage of the Challenger. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1972.

- Menard, H. W. The Ocean of Truth: A Personal History of Plate Tectonics. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986.

- Parry, J. H. The Discovery of the Sea. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974.

- Rozwadowski, Helen M. Fathoming the Ocean: The Discovery and Exploration of the Deep Sea. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005.

- Schlee, Susan. The Edge of an Unfamiliar World: A History of Oceanography. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1973.

The Poles

- Beattie, Owen, and John Geiger. Frozen in Time: The Fate of the Franklin Expedition. Toronto: Greystone Books, 1998.

- Belanger, Dian Olson. Deep Freeze: The United States, the International Geophysical Year, and the Origins of Antarctica’s Age of Science. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2006.

- Joyner, Christopher C. Governing the Frozen Commons: The Antarctic Regime and Environmental Protection. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998.

- Pyne, Stephen J. The Ice: A Journey to Antarctica. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1986

- Peterson, J. J. Managing the Frozen South: The Creation and Evolution of the Antarctic Treaty System. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

- Rose, Lisle E. Assault on Eternity: Richard E. Byrd and the Exploration of Antarctica, 1946–47. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1980.

- Sullivan, Walter. Assault on the Unknown: The International Geophysical Year. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961.

Space

- Burrows, William E. Exploring Space: Voyages in the Solar System and Beyond. New York: Random House, 1990.

- Burrows, William E. This New Ocean: The Story of the First Space Age. New York: Modern Library, 1999.

- Chaikin, Andrew. A Man on the Moon. New York: Penguin, 1994.

- Cooper, Henry S. F., Jr. The Evening Star: Venus Observed. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994.

- Cooper, Henry S. F., Jr. Imaging Saturn: The Voyager Flights to Saturn. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1982.

- Cooper, Henry S. F., Jr. The Search for Life on Mars: Evolution of an Idea. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1981.

- Hartmann, William K., et al, eds. In the Stream of Stars: The Soviet/American Space Art Book. New York: Workman, 1990.

- Harvey, Brian. Russia in Space: The Failed Frontier? Chicheser, UK: Praxis, 2001.

- Harvey, Brian. Russian Planetary Exploration: History, Development, Legacy and Prospects. Chichester, UK: Praxis, 2007.

- Kilgore, De Witt Douglas. Astrofuturism: Science, Race, and Visions of Utopia in Space. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

- Kraemer, Robert S. Beyond the Moon: A Golden Age of Planetary Exploration 1971–1978. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2000.

- Launius, Roger D. Apollo’s Legacy: Perspectives on the Moon Landings. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2019.

- Launius, Roger D., and Howard E. McCurdy. Robots in Space: Technology, Evolution, and Interplanetary Travel. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins Press, 2008.

- McDougall, Walter A. The Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age. New York: Basic Books, 1985.

- Miller, Ron. The Art of Space: The History of Space Art, from the Earliest Visions to the Graphics of the Modern Era. Minneapolis, Minn.: Zenith Press, 2014.

- Murray, Bruce. Journey into Space: The First Thirty Years of Space Exploration. New York: W. W. Norton, 1989.

- Poole, Robert. Earthrise: How Man First Saw the Earth. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2008.

- Pyne, Stephen J. Voyager: Seeking Newer Worlds in the Third Great Age of Discovery. New York: Viking, 2010.

- Roland, Alex. A Spacefaring People: Perspectives on Early Spaceflight. Washington, D.C.: NASA, 1985.

- Sagan, Carl. Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space. New York: Ballantine, 1994.

- Westwick, Peter J. Into the Black: JPL and the American Space Program 1976–2004. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Wilkins, Don E. To a Rocky Moon: A Geologist’s History of Lunar Exploration. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1993.

- Wilson, J. Tuzo. IGY: The Year of the New Moons. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1961.