.jpg.webp) | |

| Date | 25 January 2019 |

|---|---|

| Location | Córrego do Feijão iron ore mine, Brumadinho, Minas Gerais, Brazil |

| Coordinates | 20°07′11″S 44°07′17″W / 20.11972°S 44.12139°W |

| Type | Dam failure |

| Participants | Vale |

| Deaths | 270 |

| Missing | 6 (included in reported deaths) |

| Arrests | 13 |

The Brumadinho dam disaster occurred on 25 January 2019 when a tailings dam at the Córrego do Feijão iron ore mine suffered a catastrophic failure.[1] The dam, located 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) east of Brumadinho in Minas Gerais, Brazil, is owned by the mining company Vale, which was also involved in the Mariana dam disaster of 2015.[2] The collapse of the dam released a mudflow that engulfed the mine's headquarters, including a cafeteria during lunchtime, along with houses, farms, inns, and roads downstream.[3][4][5][6] 270 people died as a result of the collapse, of whom 259 were officially confirmed dead, in January 2019, and 11 others were reported as missing. As of January 2022 there were still 6 missing.[7][8][9]

Background

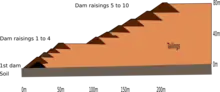

The Córrego do Feijão tailings dam, built in 1976 by Ferteco Mineração and acquired by the iron ore mining corporation Vale S.A. in 2001, was classified as a small structure with a low risk of high potential damage, according to the registry of the National Mining Agency. In a statement, the State Department of Environment and Sustainable Development reported that the venture was duly licensed. In December 2018, Vale obtained a license to reuse waste from the dam (about 11.7 million cubic meters) and to close down activities. The dam had not received tailings since 2014 and, according to the company, underwent bi-weekly field inspections.[10]

Vale SA had knowledge of problems with sensors monitoring the dam's structural integrity.[11]

Mariana dam disaster

The Brumadinho dam failure occurred three years and two months after the Mariana dam disaster of November 2015, which killed 19 people and destroyed the village of Bento Rodrigues. The Mariana disaster is considered the worst environmental disaster in Brazil's history and as of January 2019 was still under investigation.[12] Brazil's weak regulatory structures and regulatory gaps allowed the Mariana dam's failure.[13] Three years after the Mariana dam collapse, the companies involved in that environmental disaster have paid only 3.4% of R$785 million in fines.[14] In November 2015, the department in charge of inspecting mining operations in the state of Minas Gerais, the National Department of Mineral Production (DNPM), was worried about the retirement of another 40% of public employees over the course of the next two years.[15]

Collapse

Córrego do Feijão's Dam I collapsed just after noon, at 12:28 p.m. on 25 January 2019, unleashing a toxic tidal wave of around 12 million cubic metres of tailings. The mudflow quickly engulfed the mine's administrative area, burying hundreds of the mine's employees alive, including scores in the cafeteria during their lunch break. The deluge of mining waste continued downhill towards "Vila Ferteco", a small community about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) from the mine, killing at least seven people at a bed and breakfast and collapsing a railway bridge along the way.[16] By 3:50 p.m., the mud had travelled over 5 kilometres (3.1 mi), reaching the Paraopeba River, the region's main river, which supplies water to one-third of the Greater Belo Horizonte region.[17][18]

The Inhotim Institute, one of largest open-air art centres in Latin America, located in Brumadinho, was evacuated as a precaution, although the mudflow did not reach the sculpture park.[19][20]

On 27 January, around 5:30 a.m., sirens were sounded amid fears for the stability of the mine's adjacent Dam VI, a process water reservoir, where increased water levels were detected. Due to the risk, about 24,000 residents from several districts of Brumadinho were evacuated, including the city's downtown area. Rescue operations were suspended for several hours.[21][18][22]

Aftermath

Victims

On 26 January 2019, Vale president Fabio Schvartsman stated that most of the victims were Vale employees. Three locomotives and 132 wagons were buried and four railway workers were missing. The mud destroyed two sections of a railway bridge and about 100 metres of railway track.[23] As of January 2020, 259 people were confirmed dead, and 11 were considered missing.[7] Figures were later amended to 270 deaths.[24]

Environment

The dam failure released around 12 million cubic metres of tailings. Metals in the tailings were incorporated into the river sediments, with a higher concentration closer to the site of the spill. Analyses of the river sediment were conducted downstream for 27 elements, showing some minor increases in metal concentrations. Severe concentrations of cadmium were found at Retiro Baixo, some 302 km (188 mi) downstream from the mine site.[25]

Vale's president, Fabio Schvartsman, said that the dam had been inactive since 2015 and that the material should not be moving too much. "I believe that the environmental risk, in this case, will be much lower than that of Mariana", he said.[26]

Economic impact

As a result of the disaster, on 28 January the Vale S.A. stock price fell 24%, losing 71.3 billion reais (US$19 billion) in market capitalization, the biggest single-day loss in the history of the Brazilian stock market, surpassing May 2018, when Petrobrás lost more than R$47 billion in market value. By the end of 28 January, Vale's debt was downgraded to a rating of BBB− by Fitch Ratings.[27]

In the city of Brumadinho, many agricultural areas were affected or totally destroyed. The local livestock industry suffered damages, mainly from the loss of animals such as cattle and poultry. The local market was also impacted due to the damages, with some stores and establishments remaining closed for a few days.

Impact on the public water supply

The water supply company Companhia de Saneamento de Minas Gerais (COPASA) stated that the tailings had not compromised public water supply,[28] but as a precaution, suspended collection of the river water in the communities of Brumadinho, Juatuba, and Pará de Minas.[29] Due to the importance of the river for the municipality, the Agência Reguladora dos Serviços de Água e Esgoto de Pará de Minas (ARSAP) reported that operations could go on as normal.[30]

Following assessment by state and federal health, environment, and agriculture agencies, the Minas Gerais Government announced on 31 January that raw water from the Paraopeba River, from its confluence with Ribeirão Ferro-Carvão to Pará de Mina, posed risks to human and animal health and should not be consumed.[31] Tests demonstrated that twenty other municipalities were affected by the dam’s collapse.[32] The effects of the pollution impacted communities at least 120 km (75 mi) beyond Brumadhino.[33]

Reactions

President of Brazil Jair Bolsonaro sent three ministers to follow the rescue efforts.[34] The Governor of Minas Gerais, Romeu Zema, announced the formation of a task force to rescue the victims.[35]

The Israeli government sent a 130-strong group including specialist engineers, doctors, search and rescue teams, firefighters and naval divers to Brumadinho to aid Brazilian specialists in finding possible survivors.[36][37][38]

On 29 January, Brazilian authorities issued arrest warrants for five employees believed to be connected with the dam collapse, leading to two senior managers of the mine and another Vale employee being arrested, alongside two engineers from the German company TÜV Süd who had been contracted to inspect the dam.[39][40][41]

The local mining union's treasurer called the disaster "premeditated" as there were continuous and long-standing complaints and warnings about the structural integrity of the dam. Vale denied these charges and stated the mine was up-to-date with the latest standards.[40]

One day after the failure, the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources announced a R$250 million fine on the Vale company.[42]

Brazilian judicial authorities froze US$3 billion of Vale's assets, saying real estate and vehicles would be seized if the company could not come up with the money.[43]

In April, Vale's safety inspectors refused to guarantee the stability of at least 18 of its dams and dikes in Brazil.[44]

Brazilian prosecutors announced in January 2020 that Vale SA, auditor TÜV Süd, and 16 individuals, including Vale's ex-president Fabio Schvartsman, would be charged with intentional homicide and environmental offences.[45][46][47] In January 2021, a group of Brazilian claimants brought the first civil lawsuit on German soil against TÜV Süd.[48]

In February 2021, the state government reached an agreement with Vale to repair all environmental damage, and to pay the communities affected socio-economic and socio-environmental reparations, initially estimated at US$7 billion.[45]

See also

References

- ↑ Schvartsman, Fabio (25 January 2019). "Announcement about Brumadinho breach dam" (in Portuguese). Vale. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ↑ "Barragem de rejeitos da Vale se rompe e causa destruição em Brumadinho (MG)" [Vale's tailings dam collapses and causes destruction in Brumadinho, Minas Gerais]. Correio Braziliense (in Brazilian Portuguese). 25 January 2019. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ↑ Phillips, Dom (6 February 2019). "'That's going to burst': Brazilian dam workers say they warned of disaster". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ↑ "Clarifications regarding Dam I of the Córrego do Feijão Mine". Vale. Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ↑ "Barragem da Vale se rompe em Brumadinho, na Grande BH" [Vale's tailings dam collapses in Brumadinho, in Belo Horizonte metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte]. G1 (in Portuguese). 26 January 2019. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ↑ "Brumadinho dam collapse in Brazil: Vale mine chief resigns". BBC News. 3 March 2019. Archived from the original on 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- 1 2 Plumb, Christian; Nogueira, Marta (8 January 2020). "Exclusive: Brazil prosecutor aims to charge Vale within days over mining waste dam disaster". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021 – via www.reuters.com.

- ↑ "Brumadinho: mais duas vítimas do rompimento da barragem da Vale são identificadas". G1 Minas (in Brazilian Portuguese). Belo Horizonte, Brazil. 28 December 2019. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ↑ "Brazil: Dam collapse in Brumadinho marks 3 years with families waiting for reparations, six victims still missing and no one held responsible". www.business-humanrights.org. Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. 24 January 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ↑ "Brumadinho: O que se sabe sobre o rompimento de barragem que matou ao menos 58 pessoas em MG". BBC News Brasil (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ↑ "Vale knew about sensor problems at dam before burst – Globo TV". Mining.com. 16 February 2019. Archived from the original on 24 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ↑ "Tragédia em Brumadinho acontece três anos após desastre ambiental em Mariana". Jornal Nacional. Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ↑ dos Santos, Rodrigo Salles Pereira; Milanez, Bruno (2017). "The construction of the disaster and the "privatization" of mining regulation: reflections on the tragedy of the Rio Doce Basin, Brazil". Vibrant: Virtual Brazilian Anthropology. 14 (2). doi:10.1590/1809-43412017v14n2p127.

- ↑ "Empresas envolvidas em desastres ambientais quitaram só 3,4% de R$ 785 milhões em multas". O Globo (in Brazilian Portuguese). 6 May 2018. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ↑ "Minas tem apenas quatro fiscais para vistoriar barragens e não há previsão de concurso". Estado de Minas (in Brazilian Portuguese). 19 November 2015. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ↑ Darlington, Shasta; Glanz, James; Andreoni, Manuela; Bloch, Matthew; Peçanha, Sergio; Singhvi, Anjali; Griggs, Troy (9 February 2019). "Brumadinho Dam Collapse: A Tidal Wave of Mud". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ↑ "Tragédia em Brumadinho: 58 mortes confirmadas, 19 corpos identificados, lista tem 305 pessoas sem contato; SIGA". G1 (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- 1 2 "Brazil dam rescue resumes after second barrier ruled safe", Sky, archived from the original on 7 November 2020, retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ↑ Rebello, Aiuri; Ramalhoso, Wellington. "Barragem se rompe em Brumadinho e atinge casas; vítimas são levadas a BH" [Dam collapses in Brumadinho and hits homes; victims are taken to Belo Horizonte]. UOL (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ↑ Angeleti, Gabriella (4 March 2019). "Inhotim arts centre reopens in wake of deadly Brazilian dam collapse". The Art Newspaper. London. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ↑ "Brazil search resumes after new dam scare". BBC News. 27 January 2019. Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ↑ "Vale updates information on the dam breach in Brumadinho". Vale. 27 January 2019. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ "Tragédia em Brumadinho:Lista da Vale de pessoas não encontradas". G1 (in Portuguese). Belo Horizonte, Brazil. 26 January 2019. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ↑ Pearson, Samantha; Magalhaes, Luciana; Kowsmann, Patricia (31 December 2019). ""Brazil's Vale Vowed 'Never Again.' Then Another Dam Collapsed." by Samantha Pearson, et al, The Wall Street Journal, December 31, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2020". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 21 January 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ↑ dos Santos Vergilio, Cristiane; Lacerda, Diego; Vaz de Oliveira, Braulio Cherene (3 April 2020). "Metal concentrations and biological effects from one of the largest mining disasters in the world (Brumadinho, Minas Gerais, Brazil)". Nature. 10 (5936): 5936. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.5936V. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-62700-w. PMC 7125165. PMID 32246081. S2CID 214783966.

- ↑ "Técnicos avaliam extensão do dano ambiental de rompimento da barragem". Jornal Nacional (in Portuguese). 26 January 2019. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ↑ Laier, Paula (28 January 2019). "Vale stock plunges after Brazil disaster; $19 billion in market value lost". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ↑ "CLARIFICATION NOTE 11 - B1 DAM DISASTER". meioambiente.mg. Instituto Mineiro de Gestão das Águas. Archived from the original on 5 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ↑ "Por precaução a captação de águas do Rio Paraopeba está suspensa no município" (in Portuguese). Prefeitura de Paraopeba. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ↑ Mazzoco, Heitor (29 January 2019). "With mud, Pará de Minas will have a long-term supply problem". Otempo. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ↑ "Paraopeba water is unfit for consumption, warns Government of Minas". Bhaz. 31 January 2019. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ↑ Lopes, Nathan. "Tragedy Brumadinho". uol. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ↑ "Ten towns hit by river pollution from Brazil dam disaster". Phys.org. AFP. 13 February 2019. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ↑ Ernesto, Marcelo (25 January 2019). "Em mensagem, Bolsonaro lamenta rompimento de barragem em Brumadinho" [In a message, Bolsonaro mourned the tailings dam collapse in Brumadinho]. Estado de Minas (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ↑ da Fonseca, Marcelo (25 January 0214). "Governo de Minas cria força-tarefa para acompanhar barragem de Brumadinho" [Minas Gerais government creates task-force to monitor Brumadinho's dam]. Correio Braziliense (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ↑ Oliveira, Eliane (27 January 2019). "Militares de Israel que ajudarão nas buscas em Brumadinho embarcam para o Brasil". O Globo (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ↑ Roberto, Jose. "Israel posta imagens dos militares que ajudarão em Brumadinho". VEJA.com (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ↑ "Israeli rescue team arrives in Brazil as dam collapse toll hits 58". Times of Israel. AP. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ↑ "Brazil dam disaster death toll mounts as arrests warrants issued". CBS News. 29 January 2019. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- 1 2 "3 Brazil mining company employees, 2 contractors arrested in dam disaster". CBC News. Thomson Reuters. 29 January 2019. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ↑ Silva De Sousa, Marcelo; Jeantet, Diane (31 January 2019). "Brazilian environmental group tests water after dam collapse". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ↑ "Ibama multa Vale em R$ 250 milhões por tragédia em Brumadinho". noticias.uol.com.br (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ↑ "New alert as hundreds feared dead in Brazil dam disaster". São Paulo. Agence France-Presse. 27 January 2019. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ↑ Pearson, Samantha; Magalhaes, Luciana (1 April 2019). "Inspectors Fail to Guarantee Safety of 18 Vale Dams, Dikes in Brazil -- 2nd Update". Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- 1 2 "Vale dam disaster: $7bn compensation for disaster victims". BBC News. London. 4 February 2021. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ↑ Costa, Luciano (21 January 2021). "Brazil to file charges on Tuesday against miner Vale for dam disaster". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ↑ Millard, Peter; Valle, Sabrina (22 January 2020). "From Mining Savior to Homicide Charges, the Fall of Vale's Chief". Bloomberg. New York. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ↑ "TÜV SÜD Hit by 'Significant Damages' Claim in Germany Over 2019 Brazil Dam Tragedy". Insurance Journal. 22 January 2021. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

External links

- Burton, Katie (20 March 2019). "Why the Brumadinho dam collapse wasn't surprising". Geographical Magazine. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Carneiro, Julia (1 January 2019). "Brazil dam disaster: Inside the village destroyed by surging sludge". BBC News Brasil. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Nogueira, Elton P. (17 March 2021). "Judicial rulings Minas Gerais State x Vale S. A. Brumadinho Dam judicial procedure". Decisões Judiciais No Processo Entre O Ministério Público e Estado de Minas Gerais Contra a Vale S. A. Pelo Rompimento da Barragem de Brumadinho (Mg) (in Portuguese). Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Nogueira, Elton P. (2021). "Brumadinho Dam Rupture Judicial Class Action Case Study". Academia Letters. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- Pollock, Emily (18 February 2019). "Manufactured Disaster: How Brazil's Dam Collapse Should Have Been Avoided". Engineering.com. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- "The safety business: TÜV SÜD's role in the Brumadinho dam failure in Brazil". ECCHR. Berlin: European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights. 17 October 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

Media related to Brumadinho dam disaster at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Brumadinho dam disaster at Wikimedia Commons