| Bittersweet nightshade | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Solanum dulcamara[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Solanaceae |

| Genus: | Solanum |

| Species: | S. dulcamara |

| Binomial name | |

| Solanum dulcamara | |

Solanum dulcamara is a species of vine in the genus Solanum (which also includes the potato and the tomato) of the family Solanaceae. Common names include bittersweet, bittersweet nightshade, bitter nightshade, blue bindweed, Amara Dulcis,[3] climbing nightshade,[4] felonwort, fellenwort, felonwood, poisonberry, poisonflower, scarlet berry, snakeberry,[5][6][7] trailing bittersweet, trailing nightshade, violet bloom, and woody nightshade.

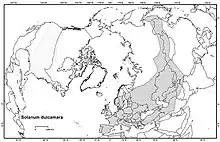

It is native to Europe and Asia, and widely naturalised elsewhere, including North America.

Overview

It occurs in a very wide range of habitats, from woodlands to scrubland, hedges and marshes.

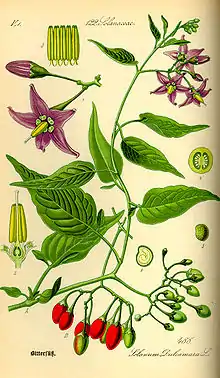

Solanum dulcamara is a very woody herbaceous perennial vine, which scrambles over other plants, capable of reaching a height of 4 m where suitable support is available, but more often 1–2 m high. The leaves are 4–12 cm long, roughly arrowhead-shaped, and often lobed at the base. The flowers are in loose clusters of 3–20, 1–1.5 cm across, star-shaped, with five purple petals and yellow stamens and style pointing forward. The fruit is an ovoid red berry about 1 cm long,[8] soft and juicy, with the aspect and odour of a tiny tomato, and edible for some birds, which disperse the seeds widely. However, the berry is poisonous to humans and livestock,[9][10] and the berry's attractive and familiar look make it dangerous for children.

It is native to northern Africa, Europe, and Asia, but has spread throughout the world. The plant is relatively important in the diet of some species of birds such as European thrushes,[11] which feed on its fruits, being immune to its poisons, and scatter the seeds abroad. It grows in all types of terrain with a preference for wetlands[12] and the understory of riparian forests. Along with other climbers, it creates a dark and impenetrable shelter for varied animals. The plant grows well in dark areas in places where it can receive the light of morning or afternoon. An area receiving bright light for many hours reduces its development.[12] It grows more easily in rich wet soils with plenty of nitrogen. When grown for medicinal purposes, it is best grown in a dry, exposed environment.[13]

It is a nonnative species in the United States.[14]

History

Solanum dulcamara has been valued by herbalists since ancient Greek times. In the Middle Ages the plant was thought to be effective against witchcraft, and was sometimes hung around the neck of cattle to protect them from the "evil eye".[15][16][17] It has been suggested that the plant was used both medicinally and to induce altered states of mind in Anglo-Saxon England.[18]

John Gerard's Herball (1597) states that "the juice is good for those that have fallen from high places, and have been thereby bruised or beaten, for it is thought to dissolve blood congealed or cluttered anywhere in the intrals and to heale the hurt places."[17]

Biological activity

This plant is one of the less poisonous members of the Solanaceae. Instances of poisoning in humans are very rare on account of the fruit's intensely bitter taste. Incidentally, the fruit has been reported to have a sweet aftertaste, hence the vernacular name bittersweet.[19]

The poison in this species is believed to be solanine.[20] The alkaloids, solanine (from unripe fruits), solasodine (from flowers) and beta-solamarine (from roots) have been found to inhibit the growth of E. coli and S. aureus.[21] Solanine and solasodine extracted from Solanum dulcamara showed antidermatophytic activity against Chrysosporium indicum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes and T. simil, thus it may cure ringworm.[22]

The stems are approved by the German Commission E for external use as supportive therapy in chronic eczema.[23]

Medicinal use

Solanum dulcamara has a variety of documented medicinal uses, all of which are advised to be approached with proper caution as the entirety of the plant is considered to be poisonous. Always seek advice from a professional before using a plant medicinally. There have only been records of medicinal use for adults (not children) and it is possible to be allergic to Solanum dulcamara; medicinal use is not advised in these cases.[24]

Use of stem

The stem of Solanum dulcamara is believed to be considerably less poisonous than the rest of the plant, and it has mostly been used in treatment for conditions of the skin. There are records of it being used to treat mild recurrent eczema, psoriasis, scabies, and dermatomycosis.[25][26] Stems are harvested when they do not yet have leaves (or the leaves have already fallen) and are shredded into small pieces. They are mostly known to be applied in the form of liquid onto the skin, but infusing it into a drink is also possible, though not recommended.[27] The stem has also been used in treatment for bronchitis, asthma, and pneumonia.[26]

Use of leaves, fruit, and root

The leaves of Solanum dulcamara have been known to treat warts and tumors, while the fruit can treat conditions of the respiratory tract and joints.[24] It has been documented that Indigenous people of North America used the roots for relief of fever and nausea.[28]

Symbolism

Solanum dulcamara has been used as a symbol of fidelity. This is in reference to its curious property of combining extreme bitterness with surprising sweetness – hence its common name "bittersweet". This symbolism is seen in Christian art from the Middle Ages as well as in bridal wreaths.[29]

Gallery

Flowers

Flowers Fruits

Fruits Solanum dulcamara

Solanum dulcamara Bittersweet Nightshade in Clark County, Ohio.

Bittersweet Nightshade in Clark County, Ohio. Bittersweet after rain in Boston, Massachusetts

Bittersweet after rain in Boston, Massachusetts

References

- ↑ illustration by Kurt Stüber, published in Prof. Dr. Otto Wilhelm Thomé Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz 1885, Gera, Germany

- ↑ Sp. Pl. 1: 185. 1753 [1 May 1753] "Plant Name Details for Solanum dulcamura". IPNI. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ↑ Culpeper Plant Names Database, discussing various editions of Culpeper, for example Culpeper, Nicholas, The English physitian: or an astrologo-physical discourse of the vulgar herbs of this nation, London, Peter Cole, 1652.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS (n.d.). "Solanum dulcamara". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ↑ Blanchan, Neltje (2005). Wild Flowers Worth Knowing. Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation.

- ↑ "Almost any unfamiliar berry is or may be snake-berry, and all snake-berries are poisonous; so a boy dares not eat a berry till some one . . . ". Needs verification but may come from Fannie D. Bergen (November 1892). "Popular American Plant Names". Botanical Gazette. 17 (11): 363–380. doi:10.1086/326860. S2CID 224830265.

- ↑ "Guide to Poisonous and Toxic Plants (Technical Guide #196)". US Army center for health promotion and preventive medicine, Entomological Sciences Program. July 1994. Archived from the original on May 4, 2008.

- ↑ Parnell, John A. N.; Cullen, Elaine L.; Webb, D. A.; Curtis, Tom (2011). Webb's an Irish flora. Cork: Cork University Press. ISBN 978-1-909005-08-2. OCLC 830022856.

- ↑ Victor King Chesnut (1898). "Bittersweet". Thirty Poisonous Plants of the United States. U.S. Department of Agriculture. pp. 31–32. Retrieved 2017-07-22.

- ↑ Umberto Quattrocchi (2016). CRC World Dictionary of Medicinal and Poisonous Plants: Common Names, Scientific Names, Eponyms, Synonyms, and Etymology (5 Volume Set). CRC Press. p. 3481. ISBN 978-1-4822-5064-0. Retrieved 2017-07-22.

- ↑ Jones, Theresa. "Climbing nightshade". Outdoor Learning Lab. Greenfield Community College. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- 1 2 "Solanum dulcamara". www.fs.usda.gov. Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ↑ "Solanum dulcamara Bittersweet. Bittersweet Nightshade, Climbing nightshade, Bittersweet, Deadly Nightshade, Poisonous PFAF Plant Database". pfaf.org. Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ↑ "Solanum dulcamara". US Forest Service. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ↑ Drage, William (1665). Daimonomageia. A small treatise of sicknesses and diseases from witchcraft and supernatural causes, etc. p. 39.

- ↑ Culpeper, Nicholas (October 2006). Culpeper's Complete Herbal & English Physician. Applewood Books. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9781557090805.

- 1 2 Grieve, Maud (1971). A Modern Herbal: The Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-lore of Herbs, Grasses, Fungi, Shrubs, & Trees with All Their Modern Scientific Uses, Volume 1.

- ↑ Alaric Hall, 'Madness, Medication—and Self-Induced Hallucination? Elleborus (and Woody Nightshade) in Anglo-Saxon England, 700–900', Leeds Studies in English, new series, 44 (2013), 43-69 (pp. 60–62).

- ↑ Mabey, Richard; Gibbons, Bob; Jones, Gareth Lovett (1997). Flora Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 1-85619-377-2. OCLC 38725904.

- ↑ R. F. Alexander; G. B. Forbes & E. S. Hawkins (1948-09-11). "A Fatal Case of Solanine Poisoning". Br Med J. 2 (4575): 518. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4575.518. PMC 2091497. PMID 18881287.

- ↑ Kumar, Padma; Sharma, Bindu; Bakshi, Nidhi (2009-05-20). "Biological activity of alkaloids from Solanum dulcamara L.". Natural Product Research. Informa UK Limited. 23 (8): 719–723. doi:10.1080/14786410802267692. ISSN 1478-6419. PMID 19418354. S2CID 25721657.

- ↑ Bakshi, N.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, M. (2008). "Antidermatophytic activity of some alkaloids from Solanum dulcamara". Indian Drugs. 45 (6): 483–484.

- ↑ "Bittersweet Nightshade". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- 1 2 "Community herbal monograph on Solanum dulcamara L., stipites" (PDF). European Medicines Agency Science Medicines Health. 15 January 2013.

- ↑ "Woody nightshade stem" (PDF). European Medicines Agency Science Medicines Health. 12 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Целебные Травы | Паслен сладко-горький - Solanum dulcamara L." www.medherb.ru. Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ↑ "Solanum dulcamara Bittersweet. Bittersweet Nightshade, Climbing nightshade, Bittersweet, Deadly Nightshade, Poisonous PFAF Plant Database". pfaf.org. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- ↑ "BRIT - Native American Ethnobotany Database". naeb.brit.org. Retrieved 2022-10-05.

- ↑ Kandeler, Riklef; Ullrich, Wolfram R. (2009). "Symbolism of plants: examples from European-Mediterranean culture presented with biology and history of art". Journal of Experimental Botany. 60 (11): 2955–2956. doi:10.1093/jxb/erp207. ISSN 0022-0957. JSTOR 24038282. PMID 19549625.