| Ferruginous hawk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Buteo |

| Species: | B. regalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Buteo regalis (Gray, 1844) | |

| |

The ferruginous hawk (Buteo regalis) is a large bird of prey and belongs to the broad-winged buteo hawks. An old colloquial name is ferrugineous rough-leg,[2] due to its similarity to the closely related rough-legged hawk (B. lagopus).

The generic name buteo is Latin for 'buzzard'.[3] The specific epithet regalis is Latin for 'royal' (from rex, regis, 'king').[4] The common name 'ferruginous' means 'rust-colored' or 'reddish-brown'.

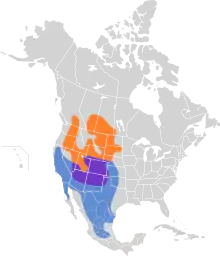

This species is a large, broad-winged hawk of the open, arid grasslands, prairie and shrub steppe country; it is endemic to the interior parts of North America. It is used as a falconry bird in its native ranges.

Description

This is the largest of the North American Buteos and is often mistaken for an eagle due to its size, proportions, and behavior. Among all the nearly thirty species of Buteo in the world, only the upland buzzard (B. hemilasius) of Asia averages larger in length and wingspan. The weight of the upland buzzard and ferruginous broadly overlaps and which of these two species is the heaviest in the genus is debatable.[5] As with all birds of prey, the female ferruginous hawk is larger than the male, but there is some overlap between small females and large males in the range of measurements. Length in this species ranges from 51 to 71 cm (20 to 28 in) with an average of 58 cm (23 in), wingspan from 122 to 158 cm (4 ft 0 in to 5 ft 2 in), with an average of about 139 cm (4 ft 7 in), and weight from 907 to 2,268 g (32.0 to 80.0 oz).[6][7][8][9][10] Weight varies in the species relatively restricted breeding range. In the southern reaches of the species breeding range, i.e. Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, males average 1,050 g (37 oz), in a sample of fifteen, and females average 1,231 g (43.4 oz), in a sample of four.[11][12] In the northern stretches of the breeding range, in southern Canada, Washington, Idaho and North Dakota, the hawks are heavier averaging 1,163 g (41.0 oz) in males (from a sample of 30) and 1,776 g (62.6 oz) in females (from a sample of 37). Upland buzzard average weights were intermediate between those body mass surveys, notably heavier than the first and less heavier than the latter one, particularly the sample of 37 ferruginous hawk females place it as the most massive type of Buteo in northern populations.[13][14]

Adults have long broad wings and a broad gray, rusty, or white tail. The legs are feathered to the talons, like the rough-legged hawk. There are two color forms:

- Light morph birds are rusty brown on the upper parts and pale on the head, neck, and underparts with rust on the legs and some rust marking on the underwing. The upper wings are grey. The "ferruginous" name refers to the rusty color of the light-morph birds.

- Dark-morph birds are dark brown on both upperparts and underparts with light areas on the upper and lower wings.

There are no subspecies.

Voice

The voice is not well-described in literature. Alarm calls consist of kree – a or ke – ah and harsh kaah, kaah calls, the latter resembling some vocalizations of the herring gull. One description referred to the "wavering" alarm call and "breathy" notes, while other authors describe screams similar to those of the red-tailed hawk (B. jamaicensis).

Identification

The male and female have identical markings. The main difference is size, with the female being somewhat larger. Perched birds have a white breast and body with dark legs. The back and wings are a brownish rust color. The head is white with a dark streak extending behind the eye. The wingtips almost reach the tip of the tail.

The underside is primarily light colored with the dark legs forming a "V" shape. The reddish upper-back color extends to the inner wing-coverts or "shoulders." The primary remiges (pinions) are dark gray with conspicuous light "windows" in the inner primaries. Three prominent light areas on the upper surface stand out as two "windows" on the outer wings and a rufous rump mark, perhaps the most significant feature of a flying ferruginous hawk. The underwings are whitish overall with rufous markings, particularly in the patagial area. This gives a smudgy appearance to the wings, but less dark than in a red-tailed hawk. The ferruginous hawk is noticeably longer winged than a red-tailed hawk, although the wings appear slenderer than the latter species the total wing area of the ferruginous is considerably more. However, the Red-tail can be nearly as bulky and heavy. Dark "comma"-shaped markings are prominent at the wrists. The ferruginous hawk is one of the only two hawks that have feathers that cover their legs down to their toes, like the golden eagle. The other is the rough-legged buzzard (Buteo lagopus). The pale morph of the closely related but more slender rough-legged species is best distinguished by its darker coloration, with a broad black tail band and a dark band across the chest. The dark morph Rough-leg is more a slaty coloration than the more brownish dark morph ferruginous. Swainson's hawks and especially rough-legged buzzards can be nearly as long-winged but are less bulky and heavily built than the ferruginous. Among the normal standard measurements, the wing chord measures 415 to 477 mm (16.3 to 18.8 in), the tarsus measures 81 to 92 mm (3.2 to 3.6 in) and the tail measures 224 to 252 mm (8.8 to 9.9 in). Additionally, the grasp is 94 to 125 mm (3.7 to 4.9 in) and the third toe 29.5 to 45 mm (1.16 to 1.77 in), indicating that the ferruginous hawks has the largest and most robust feet of any of the world's Buteos. Compared to other Buteos, the ferruginous has a larger bill, at 37.6 to 49.5 mm (1.48 to 1.95 in), with a much wider gap when the bill is opened, at 42.7 to 57 mm (1.68 to 2.24 in).[5][13]

In-flight, these birds soar with their wings in a dihedral.

Habitat

The preferred habitat for ferruginous hawks are the arid and semiarid grassland regions of North America. The countryside is open, level, or rolling prairies; foothills or middle elevation plateaus largely devoid of trees; and cultivated shelterbelts or riparian corridors. Rock outcrops, shallow canyons, and gullies may characterize some habitats. These hawks avoid high elevations, forest interiors, narrow canyons, and cliff areas.

During the breeding season, the preference is for grasslands, sagebrush, and other arid shrub country. Nesting occurs in the open areas or in trees including cottonwoods, willows, and swamp oaks along waterways. Cultivated fields and modified grasslands are avoided during the breeding period. The density of ferruginous hawks in grasslands declines in an inverse relationship to the degree of cultivation of the grasslands. However, high densities have been reported in areas where nearly 80% of the grassland was under cultivation.

The winter habitat is similar to that used during the summer. However, cultivated areas are not necessarily avoided, particularly when the crops are not plowed under after harvest. The standing stubble provides habitat for the small-mammal prey base needed by ferruginous and other hawks. One requisite of the habitat is perches such as poles, lone trees, fence posts, hills, rocky outcrops or large boulders. Ferruginous hawks nest in trees if they are available, including riparian strips, but the presence of water does not appear to be critical to them.

The ferruginous hawk maintains minimum distances from other nesting raptors but will nest closer when necessary, suggesting that the distance is not fixed. The "nearest neighbor" distance has varied from less than 1.6 km (1 mi) to as much as 6.4 km (4 mi) with an average of 3.2 km (2 mi). Nests facing different hunting territories are tolerated much closer than nests facing the same hunting territory. The minimum distance between nests is probably about one half mile on densely occupied areas. Nesting densities in several studies have varied from one pair per 10 to 6,345 km2 (4 to 2,450 sq mi). In Alberta, on one study site, there was a stable density of one pair per 10 km2 (4 sq mi), on average with little deviation from this mean. In Idaho, the average home range for four pairs of ferruginous hawk in the Snake River area was slightly over 5.2 km2 (2 sq mi).

Behavior

The flight of the ferruginous hawk is active, with slow wing beats much like that of a small eagle. Soaring with the wings held in a strong dihedral has been noted, as well as gliding with the wings held flat, or in a modified dihedral. Hovering and low cruising over the ground are also used as hunting techniques. The wing beat has been described as "fluid" by some observers.

Dietary biology

The ferruginous hawk primarily hunts small to medium-sized mammals but will also take birds, reptiles, and some insects. Mammals generally comprise 80–90% of the prey items or biomass in the diet with birds being the next most common mass component.[11]

Method of predation

These birds search for prey while flying over open country or from a perch. They may also wait in ambush outside the prey's burrow. Hunting may occur at any time of the day depending upon the activity patterns of the major prey species. A bimodal pattern of early morning and late afternoon hunting may be common. The hunting tactics can be grouped into seven basic strategies:[15]

- Perch and Wait – perching is on any elevated natural or man-made site

- Ground Perching – the hawk will stand on the ground at a rodent burrow after initially locating it from the air. As the burrowing animal reaches the surface, the hawk rises into the air and pounces upon it even while it is still underneath the loose earth.

- Low-level Flight – birds will course over the landscape within a few yards of the ground and pursue in direct, low-level chases, or they will hunt from 12 to 18 m (40 to 60 ft) above the ground.

- High-level Flight – birds will hunt while soaring, but the success rate is generally low.

- Hovering – using quickened wing beats, often in times of increased winds, the birds will search the ground and drop on the prey.

- Cooperative Hunting – mates have been known to assist each other.

- Piracy – the ferruginous hawk has been observed gathering around a hunter shooting prairie dogs, and claiming shot "dogs" by flying to them and mantling over them.

In its "strike, kill, and consume" type of predation, the prey is seized with the feet and a series of blows may be meted out, including driving the rear talon into the body to puncture vital organs. Biting with the beak may also take place. Before bringing prey to the nest, the adults will often eat the head. At the nest, birds are plucked and mammals torn into pieces before being fed to the young. Food caching has been noted, but not generally near the nest.

Prey species

The diet varies somewhat geographically, depending upon the distribution of prey species, but where the range of the ferruginous hawk overlaps, rabbits and hares are major food species along with ground squirrels and pocket gophers. In South Dakota, Thirteen-lined ground squirrels (Spermophilus tridecemlin) are dominant prey, while northern pocket gophers (Thomomys talpoides) and Great Basin pocket mouse (Perognathus parvus) was predominantly taken in Washington.[16][17] Similarly, Botta's pocket gophers (Thomomys bottae) was important prey in New Mexico along with Gunnison's prairie dogs (Cynomys gunnisoni) and desert cottontails (Sylvilagus audubonii).[18][19] Larger black-tailed jackrabbits (Lepus californicus) is the main prey in Northern Utah and Southern Idaho, comprising 83% of the total biomass.[20] These jackrabbits can weigh around 2.1 kg (4.6 lb), though young individuals are largely taken along with adults.[21][22] Similarly, they can even regularly hunt young white-tailed jackrabbits (Lepus townsendii), one of the largest Lagomorphs in North America, and adults weighing around 3.2 kg (7.1 lb) can be infrequently taken.[16][23] In one instant, a pair of ferruginous hawks succeeds at killing a large jackrabbit about 3.63 kg (8.0 lb) in weight.[24] Other Lagomorph and rodent prey include various mouse such as Eastern deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus), voles such as montane voles (Microtus montanus), Townsend's ground squirrels (Urocitellus townsendii), muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus), eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus), and giant kangaroo rats (Dipodomys ingens)[17][16][25] Mammalian prey other than Lagomorphs and rodents are uncommon, though they occasionally prey on mustelids, such as stoats (Mustela erminea), Long-tailed weasel (Neogale frenata), and black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes).[17][19][20][26]

Ferruginous hawks can also take a wide range of birds as prey. The most frequently taken avian species are western meadowlark (Sturnella neglecta) and horned larks (Eremophila alpestris) along with other Passerines, and dabbing ducks can be important prey at times.[18][17][27] They can occasionally prey on relatively large gamebirds such as common pheasants ( Phasianus colchicus), Sharp-tailed grouses (Tympanuchus phasianellus), and Sage Grouses (Centrocercus urophasianus).[16][19][27][18] Predation on corvids such as American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos), common raven (Corvus corax), Chihuahuan ravens (C.cryptoleucus) and raptors such as burrowing Owls (Athene cunicularia), barn owls (Tyto alba), and other Buteo hawks have been reported.[16][19][28][18]

Reptiles can be taken as additional prey, mainly snakes but can include lizards such as Texas horned lizards (Phrynosoma cornutum).[29] While yellow-bellied racer (Coluber constrictor) and garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis) was constituted the second most frequent prey item in Washington, other snakes such as western hognose snakes (Heterodon nasicus) and pine snakes (Pituophis melanoleucus) can be taken in other regions.[17][16] Other preys include frogs and large insects such as grasshoppers.[29]

Interspecific interaction

Conflicts over territories, food and nest-defense have been reported with several other large species of raptor and corvid, such as the great horned (Bubo virginianus) and short-eared owl (Asio flammeus), hen harrier (Circus cyaneus), red-tailed and Swainson's hawks (Buteo swainsonii), golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), accipiters (Accipiter), ravens (Corvus), and magpies (Pica). Among native raptorial birds, only larger eagles and similarly sized great horned owls can regularly outmatch this large and powerful hawk. While bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) normally only harass ferruginous hawks to pirate food from them,[30] the golden eagle can be a serious threat (in potential territorial or defensive conflicts) and predator of the ferruginous.[31][32] Although they may be attracted to similar nesting habitat,[33] in a local comparison in northwestern Texas, southwestern Oklahoma and northeastern Arizona, the typical prey taken by Swainson's hawks was quite different, being about half the weight of that of the ferruginous hawk and more focused on insects rather than mammals.[34] However, in the Morley Nelson Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area, the prey taken by red-tailed hawks and ferruginous hawks was almost exactly the same, both in terms of species and body size.[35] The prey species hunted by golden eagles are often similar, but the ferruginous hawk is locally less of lagomorph specialist where it co-exists with eagles and takes typically smaller prey, such as pocket gophers, which are generally ignored by the eagles.[36] It seems to be quite tolerant of conspecifics from adjacent territories.

Reproduction and life history

Copulation occurs during and after nest building. The egg-laying period varies with latitude, weather, and possibly food supply. In the Canadian parts of the range, laying occurs from the latter part of April through late June, whereas farther south laying occurs from about March 20 through mid May. The earliest recorded clutch was in January in Utah and laying could occur as late as July 3 in Canada. Egg-laying occurs at two-day intervals with incubation starting when the first egg is laid. Incubation is shared by both sexes with each taking approximately the same number of shifts during the 32-day average incubation period. Replacement clutches following failure appears to be rare.

Courtship flights seem to be limited in the accepted sense. Both sexes engage in high, circling flight but literature details are sketchy. Soaring activities may primarily be variations on territorial defense flights as opposed to courtship per se. The "flutter-glide" flight consists of a series of shallow, rapid wing beats interspersed with brief glides and may serve to advertise the territory. The "sky-dance" is stimulated by an intruder and consists of slow flight with deep, labored wing beats with irregular yawing and pitching that may terminate in steep dives. In the "follow-soar" maneuver, the male ferruginous hawk will fly below an intruder and escort it out of the territory.

High perching occurs from prominent places around the nest, particularly early in the breeding cycle. Aggressive actions such as attacking, talon-grasping, and pursuit have been noted by some observers. Copulation begins before construction of the new nest, and increases in frequency until the start of egg laying. The passing of food may occur before the activity. The duration of copulation is from four to 18 seconds.

The ferruginous hawk is one of the most adaptable nesters of the raptors, and will use trees, ledges, rock or dirt outcrops, the ground, haystacks, nest platforms, power poles, and other man-made structures. Within some broad categories such as cliffs, the variety includes clay, dirt and rock substrates. Tree nests are typically in isolated trees or isolated clumps of trees in exposed locations. Authors differ as to whether ground nests are more successful than tree nests, but they are more susceptible to mammalian predation. Nest locations are reused frequently, but several nests may be built in an area. Typically, one or two alternate nests may exist but up to eight have been found on some territories.

The nests are made of ground debris such as sticks, branches, and cattails. Old nests will be refurbished, or nests of other species may be taken over and refurbished with sticks being added on top of the old nests. Odd items such as paper, rubbish, barbed wire, cornstalks, plastic, and steel cable have been incorporated into nests. Bark from trees and shrubs will be used for lining along with grasses and cow dung. Bits and pieces of greenery are often added to the nest. Prior to the removal of the bison from this bird's range, nesting material often included bison bones, fur[37] and dung. Both sexes are involved with building the nests and bringing materials, but the male seems to be more involved in retrieving materials while the female arranges them in the structure.

Clutch size varies from one to eight and is likely linked to food supply. The average clutch is three to four eggs, each 64 mm (2.5 in) long and 51 mm (2 in) wide. They are smooth, non-glossy and whitish in color, irregularly spotted or speckled and blotched with reddish-brown markings. There may be a concentration of darker pigments at the small end of the egg. Occasionally, the eggs are almost unmarked or have faint scribblings on them.

The nestling period varies from 38 to 50 days with brooding primarily by the female. Males fledge at 38 to 40 days and the females as late as 50 days after hatching, or 10 days later than their male siblings as they take longer to develop. Nestlings lie or sit for the first two weeks, stand at about three weeks and walk soon after. By 16 or 18 days, they are able to feed on their own. Wing flapping starts about day 23 and by day 33 the young are capable of vigorous flapping and "flap jumps." The nestlings are sensitive to high temperatures and seek shade however possible in the nest.

Initial movement out of the nest is felt to be a response to heat stress as the young quickly move towards shade. The initial flight for the males is taken at 38 to 40 days while the slower-developing females fly about 10 days later. Post-fledging dependency upon the parents may last for several weeks. During the first four weeks after fledging, the young patrol increasingly large areas around the nest as they learn to hunt. Young hawks have killed prey as early as four days after fledging.

The ferruginous hawk is single-brooded, and as in so many raptors, the number of young reared is tied closely to food supply. In areas where jackrabbit populations are the principal food source, the initial clutch sizes and the number of reared young vary closely with variations in the number of jackrabbits. Fifty percent loss of young has been reported in low jackrabbit years. Fledging rates of 2.7 to 3.6 young per nest have been reported during years of abundant food supply. The high potential clutch size allows for a quick response to increases in the prey base.

Ferruginous hawks have been known to live for 20 years in the wild,[38] but most birds probably die within the first five years. The oldest banded birds were recovered at age 20. First-year mortality has been estimated at 66% and the adult mortality at 25%. The reasons for mortality include illegal shooting, loss of a satisfactory food supply, harassment, predation, and starvation of nestlings during times of low food supply. Ground nests are susceptible to predation by coyotes, bobcats and mountain lions while nestlings, fledglings and adults may be preyed upon by great horned owls, red-tailed hawks, bald eagles and golden eagles.

Status and conservation

At times the ferruginous hawk has been considered threatened, endangered, or of concern on various threatened species lists but recent population increases in local areas, coupled with conservation initiatives, have created some optimism about the bird's future. It was formerly classified as a Near Threatened species by the IUCN, but new research has confirmed that the Ferruginous hawk is common and widespread again. Consequently, it was downlisted to Least Concern status in 2008.[1]

Declines are mostly due to loss of quality habitat. Although flexible in choosing a nest site and exhibiting a high reproductive potential, this bird's restriction to natural grasslands on the breeding grounds and specialized predation on mammals persecuted on rangelands may make conservation a continuous concern. Historically, the birds entirely disappeared from areas where agriculture displaced the natural flora and fauna; for example it was noted in 1916 that the species was "practically extinct" in San Mateo County, California.[2] Studies have found that prairie dogs can be a main prey item for ferruginous hawks, linking them to the populations of prairie dog towns in the mid-west and southwestern United States, which have been declining in recent years. This bird may also be sensitive to the use of pesticides on farms; they are also frequently shot. Threats to the overall population include:

- cultivation of native prairie grassland and subsequent habitat loss

- tree invasion of northern grassland habitats

- reductions in food supply due to agricultural pest management programs

- shooting and human interference

The ferruginous hawk was on the National Audubon Society's "Blue List" of species felt to be declining. From 1971 to 1981 it retained its "blue" status, and from 1982 to 1986 it was listed as a species of "Special Concern." The United States Fish and Wildlife Service placed it in a category of "undetermined" in 1973, and various states have placed it in categories of "Threatened" or "Endangered." In Canada, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada considered this species "Threatened" in 1980.

Across the Canadian prairies, the range was diminishing up until 1980, and at that time, birds were felt to be occupying 48% of its original range. Numbers were generally felt to be diminishing and a total Canadian population was estimated at 500 to 1000 pairs. By 1987, population increases were being noted, and the Alberta population alone was estimated at 1,800 pairs. The upswing was likely due to a greater availability of food on the wintering grounds, making the birds more likely to breed when they returned to Canada. In the United States, there has been a history of concern for this species in many states with declines noted, but in 1988, one study suggested that the population in California and locally elsewhere may have increased significantly. The wintering population north of Mexico was estimated at 5,500 birds in 1986. In 1984, the population estimate for North America was between 3,000 and 4,000 pairs, and in 1987, it was 14,000 individuals.

Toxic chemicals have not been suggested as a significant threat to the ferruginous hawk. Management strategies must include the retention or reclamation of native grasslands for breeding as well as on the wintering grounds. Maintenance of high populations of prey species in wintering areas seems critical to the hawks' abilities to move onto the summer range in breeding condition. The integration of agricultural practices and policies into the management strategies is a crucial component of any overall scheme for conservation. The provision of nesting platforms has had positive effects and should be a part of local strategies. Public education and the elimination of persecution and human disturbance must be an important part of the overall conservation program.

Use in falconry

The ferruginous hawk is a well-regarded falconry bird, though not recommended for beginners due to its large size, power, and aggressive personality.[39] For the experienced falconer it offers an opportunity to experience the nearest equivalent to hunting with the golden eagle with much lower risk of injury to the falconer by the hawk. Faster and stronger than the red-tailed hawk, the ferruginous hawk is effective in pursuit of larger hares and jackrabbits that are difficult prey for the red-tailed hawk and Harris's hawk, and with its agility is also more effective on large bird species than is the golden eagle.

References

- Part of this article incorporates text from the Bureau of Land Management, which is in the public domain.

- 1 2 BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo regalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22695970A93535999. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695970A93535999.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- 1 2 Littlejohn, Chase (1916). "Some unusual records for San Mateo County, California. Abstract in the Minutes of Cooper Club Meetings" (PDF). Condor. 18 (1): 38–40. doi:10.2307/1362896. JSTOR 1362896.

- ↑ Jobling, James A. (2010). "Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird-names". p. 81. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ↑ Jobling (2010), p.332

- 1 2 Ferguson-Lees J, Christie D (2001). Raptors of the World. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-8026-1.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-13. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Rogers, Katherine. (2002) Buteo regalis. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

- ↑ Raptor identification Archived 2012-02-13 at the Wayback Machine. blm.gov

- ↑ Ferruginous Hawk, Life History, All About Birds – Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

- ↑ Olendorff, R. R. (1993). Status, biology, and management of ferruginous hawks: a review. US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Raptor Research and Technical Assistance Center.

- 1 2 del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Christie, D.A. eds. Handbook of the Birds of the World, Volume 2: New World Vultures to Guineafowl. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

- ↑ Snyder, N. F., & Wiley, J. W. (1976). Sexual size dimorphism in hawks and owls of North America (No. 20). American Ornithologists' Union.

- 1 2 Gossett, D. N. 1993. Studies of Ferruginous Hawk biology: I. Recoveries of banded Ferruginous Hawks from presumed eastern and western subpopulations. II. Morphological and genetic differences of presumed subpopulations of Ferruginous Hawks. III. Sex determination of nestling Ferruginous Hawks. Master's Thesis. Boise State University, Boise, ID.

- ↑ Dunning, John B. Jr., ed. (2008). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses (2nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-6444-5.

- ↑ Wakeley, James S. "Activity periods, hunting methods, and efficiency of the ferruginous hawk." Raptor Research 8.3/4 (1974): 67-72.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Blair, Charles L., and Frank Schitoskey Jr. "Breeding biology and diet of the Ferruginous Hawk in South Dakota." The Wilson Bulletin (1982): 46-54.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richardson, Scott A., et al. "Prey of ferruginous hawks breeding in Washington." Northwestern Naturalist (2001): 58-64.

- 1 2 3 4 Keeley, William Hanlon. "Diet and behavior of Ferruginous Hawks nesting in two grasslands in New Mexico with differing anthropogenic alteration." (2009).

- 1 2 3 4 Cartron, Jean-Luc E., Paul J. Polechla Jr, and Rosamonde R. Cook. "Prey of nesting ferruginous hawks in New Mexico." The Southwestern Naturalist 49.2 (2004): 270-276.

- 1 2 Howard, Richard P. "Breeding ecology of the ferruginous hawk in northern Utah and southern Idaho." (1975).

- ↑ Woffinden, N. D. and J. R. Murphy. 1977. Population dynamics of the ferruginous hawk during a prey decline. Grt. Basin Nat. 37: 411-425.

- ↑ Platt, Joseph B. "A survey of nesting hawks, eagles, falcons and owls in Curlew Valley, Utah." The Great Basin Naturalist (1971): 51-65.

- ↑ Ensign, John Thomas. Nest site selection, productivity, and food habits of ferruginous hawks in southeastern Montana. Diss. Montana State University-Bozeman, College of Letters & Science, 1983.

- ↑ Bent, A. C. (1937). Life Histories of North American Birds of Prey: Order Falconiformes. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Watson, JAMES W., and D. JOHN Pierce. "Migration and winter ranges of ferruginous hawks from Washington." Final Report. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Olympia, WA (2003).

- ↑ Forrest, Steven C., et al. "Population attributes for the black-footed ferret Mustela nigripes at Meeteetse, Wyoming, 1981–1985." Journal of Mammalogy 69.2 (1988): 261-273.

- 1 2 Gilmer, David S., and Robert E. Stewart. "Ferruginous hawk populations and habitat use in North Dakota." The Journal of Wildlife Management (1983): 146-157.

- ↑ Keeley, William H.; Bechard, Marc J.; Garber, Gail L. (2016). Prey use and productivity of ferruginous hawks in rural and exurban New Mexico. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 80(8), 1479–1487.

- 1 2 Giovanni, Matthew D., Clint W. Boal, and Heather A. Whitlaw. "Prey use and provisioning rates of breeding Ferruginous and Swainson's hawks on the southern Great Plains, USA." The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 119.4 (2007): 558-569.

- ↑ Jorde, D. G.; Lingle, G. R. (1988). "Kleptoparasitism by Bald Eagles Wintering in South-Central Nebraska". Journal of Field Ornithology: 183–188.

- ↑ Plumpton, D. L., & Andersen, D. E. 1997. Habitat use and time budgeting by wintering ferruginous hawks. Condor: 888-893.

- ↑ Editor, (2000), Golden Eagle Pair Kills Ferruginous Hawk, Journal of Raptor Research, 34 (3): 245-246.

- ↑ Restani, M (1991). "Resource partitioning among three Buteo species in the Centennial Valley, Montana". The Condor. 93 (4): 1007–1010. doi:10.2307/3247736. JSTOR 3247736.

- ↑ Giovanni, M. D.; Boal, C. W.; Whitlaw, H. A. (2007). "Prey use and provisioning rates of breeding Ferruginous and Swainson's hawks on the southern Great Plains, USA". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 119 (4): 558–569. doi:10.1676/06-118.1. S2CID 85145059.

- ↑ Steenhof, K.; Kochert, M. N. (1985). "Dietary shifts of sympatric buteos during a prey decline". Oecologia. 66 (1): 6–16. Bibcode:1985Oecol..66....6S. doi:10.1007/bf00378546. PMID 28310806. S2CID 1726706.

- ↑ Olendorff, Richard R. (1976). "The Food Habits of North American Golden Eagles". American Midland Naturalist. The University of Notre Dame. 95 (1): 231–236. doi:10.2307/2424254. JSTOR 2424254.

- ↑ Bechard, Marc J; Schmutz, Josef K (1995). "Ferruginous Hawk". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell University. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ↑ Wasser, D. E.; Sherman, P. W. (2010). "Avian longevities and their interpretation under evolutionary theories of senescence". Journal of Zoology. 280 (2): 103–155. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00671.x.

- ↑ Beebee, Frank (1984) A Falconry Manual, Hancock House Publishers, p. 76, ISBN 0888399782.

Further reading

- Cartron, J.L.E.; Polechla, P.J.; Cook, R.R. (2004). "Prey of nesting Ferruginous Hawks in New Mexico". Southwestern Naturalist. 49 (2): 270–276. doi:10.1894/0038-4909(2004)049<0270:PONFHI>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86218975.

External links

- Ferruginous hawk – Buteo regalis USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Ferruginous hawk Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- ferruginoushawk.org – ferruginoushawk.org

- Several Closeups of the ferruginous hawk

- Ferruginous hawk videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- Ferruginous hawk photo gallery VIREO