Child cannibalism or fetal cannibalism is the act of eating a child or fetus. Children who are eaten or at risk of being eaten are a recurrent topic in myths, legends, and folktales from many parts of the world. False accusations of the murder and consumption of children were made repeatedly against minorities and groups considered suspicious, especially against Jews as part of blood libel accusations.

Actual cases are on record especially during severe famines in various parts of the world. Cannibalism sometimes also followed infanticide, the killing of unwanted infants. In several societies that recognized slavery, enslaved children were at risk of being killed for consumption. Some serial killers who murdered children and teenagers are known or suspected to have subsequently eaten parts of their bodies – examples include Albert Fish and Andrei Chikatilo.

In recent decades, rumours and newspaper reports of the consumption of aborted fetuses in China and Hong Kong have attracted attention and inspired controversial artworks. Cannibalism of children is also a motive in some works of fiction and movies, most famously Jonathan Swift's satire A Modest Proposal, which proposed eating the babies of the poor as a supposedly well-intended means of reforming society.

Mythology and folktales

Children who are eaten or at risk of being eaten are a recurrent topic in mythology and folktales from many parts of the world.

Greek mythology

.jpg.webp)

In Greek mythology, several of the major gods were actually eaten as children by their own father or just barely escaped such a fate. Cronus (called Saturn in Roman mythology), once the most powerful of the gods, was dismayed by a prophecy telling him that he would one day be deposed by one of his children, just as he had formerly overthrown his own father. So as not to suffer the same fate, Cronus decided to consume all his children right after birth. But his wife and sister Rhea, unwilling to see all her children suffer such a fate, handed him a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes after the birth of Zeus, their sixth child. Apparently not noticing the difference in taste, he devoured the stone, allowing infant Zeus to grow up at some secret hiding place without his father having any idea that a threat to his power was still alive. Once grown, Zeus tricked his father into drinking an emetic that made him disgorge Zeus' swallowed siblings Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon. Being immortal gods they had survived being eaten and had indeed grown to adulthood within their father's stomach. Understandably annoyed at their father's behaviour, the siblings then rose up against Cronus, overthrowing him and the other Titans in a huge war known as Titanomachy and thus fulfilling the prophecy.

Other Greek myths tell of children killed and served to their clueless parents in an act of revenge. Learning that his brother Thyestes had committed adultery with his wife, Atreus killed and cooked Thyestes's sons, serving their flesh to their father and revealing afterwards the hands and heads of the murdered boys, shocking Thyestes into realizing what he had eaten. Tereus is another mythic father who ate the flesh of his son without knowing it. In his case, his wife Procne killed and cooked her own child to punish her husband for the rape and mutilation of her sister Philomela.

Tantalus, on the hand, is a father who murdered and boiled his son Pelops, serving his flesh to several gods in an arrogant challenge to their omniscience. But they saw through his act and brought the boy back to life, though one of them, Demeter, had absent-mindedly already eaten part of his shoulder.

Lamia was a queen who had an affair with Zeus but became insane when his wife Hera killed or kidnapped her children to punish her for the adultery. To make up for her loss, she started to kidnap any children she could find, killing and devouring them.

Christian legends

Child cannibalism also plays a role in some Christian legends. One of the miracle stories told about the 4th-century bishop Saint Nicholas (who inspired the modern figure of Santa Claus) is that he brought three children back to life who had been killed by a butcher during a terrible famine. The butcher had pickled their flesh in brine in order to sell it as pork. But Nicholas, spotting the barrel, recognized what was really inside and resurrected the butchered children by making the sign of the cross.[1]

European folktales

The (actual or attempted) consumption of children is a topic of many European folk and fairy tales. In the German fairy tale Hansel and Gretel, a witch entraps and tries to eat a pair of abandoned siblings, but Gretel kills her by pushing her into her own preheated oven. The Norwegian tale Buttercup is also about a witch trying to eat a child, but with a darker twist, since here the little boy, Buttercup, manages to save himself by killing the witch's daughter and boiling her body for the mother to eat. The witch eats the soup, thinking it "Buttercup broth", while it is actually "Daughter broth", as he comments triumphantly.[2]

In the French tale Hop-o'-My-Thumb it is an ogre rather than a witch who tries to eat children. In the English fairy tale Jack and the Beanstalk, a giant wants to eat a little boy "for breakfast", since "there's nothing he likes better than boys broiled on toast", but the boy manages to trick and kill the giant and becomes wealthy by stealing his property.[3] Similar tales were recorded in other countries, including Italy (Thirteenth).

The Juniper Tree is a dark German fairy tale in which a young boy is killed and cooked by his own stepmother, who serves his flesh to her clueless husband (his father). Other fairy tales, most famously Little Red Riding Hood, feature anthropomorphized animals eating (or trying to eat) human children, but this is not actually cannibalism, as eater and eaten belong to different species.

Baba Yaga is a supernatural being in Slavic folklore who appears as a deformed or ferocious-looking woman and likes to dine on children.[4]

Ritual practice accusations

Since the 12th century, Jews were repeatedly accused of murdering children in order to use their blood in religious rituals.[5] Often this antisemitic canard included the charge that the blood was used for the baking of matzah eaten during Passover. In Muslim countries, such blood libels are still sometimes repeated in the 21th century.[6][7]

During the witch-hunts in the early modern period, women suspected of witchcraft were repeatedly charged with killing, roasting, and eating babies in Satanic rituals.[8][9] In a Satanic panic starting in the 1980s in the United States, thousands of people have been wrongly accused of abusing children in Satanic rituals, sometimes including claims that the victims were murdered and eaten. No evidence for such acts ever happening in such a context has been found.[10][11]

Historical accounts

Famines

In severe famines, when all other provisions were exhausted, starving people repeatedly turned to cannibalism, eating the corpses of the deceased or deliberately killing others – most often children – for consumption.[12][13] Two factors put children specifically at risk: they could be more "easily snatched" and killed than adults and their flesh was often considered "more palatable" than that of the latter.[14] Famines bad enough to lead to the consumption of human flesh were usually caused either by natural disasters such as droughts or by wars and other social conflicts.[15]

Soviet Union

In the Soviet Union, several severe famines between the 1920s and the 1940s led to cannibalism. Children were particularly at risk. During the Russian famine of 1921–1922, "it was dangerous for children to go out after dark since there were known to be bands of cannibals and traders who killed them to eat or sell their tender flesh." An inhabitant of a village near Pugachyov stated: "There are several cafeterias in the village – and all of them serve up young children."[16] Various gangs specialized in "capturing children, murdering them and selling the human flesh as horse meat or beef", with the buyers happy to have found a source of meat in a situation of extreme shortage and often willing not to "ask too many questions". This led to a situation where, according to the historian Orlando Figes, "a considerable proportion of the meat in Soviet factories in the Volga area ... was human".[17]

Cannibalism was also widespread during the Holodomor, a man-made famine in Soviet Ukraine between 1932 and 1933. While most cases were "necrophagy, the consumption of corpses of people who had died of starvation", the murder of children for food was common as well. Many survivors told of neighbours who had killed and eaten their children. One woman, asked why she had done this, "answered that her children would not survive anyway, but this way she would". Moreover, "stories of children being hunted down as food" circulated in many areas, and indeed the police documented various cases of children being kidnapped and consumed.[12] The Holodomor was part of the Soviet famine of 1930–1933, which also devastated other parts of the Soviet Union. In Kazakhstan, villagers "discovered people among them who ate body parts and killed children" and a survivor remembered how he repeatedly saw "a little foot float[ing] up, or a hand, or a child's heel" in cauldrons boiling over a fire.[18]

During the German siege of Leningrad in 1941–1944, thousands of people were arrested for cannibalism. In most cases, parts of corpses were eaten, but children were also entrapped for consumption. A woman who had been a young girl during the siege had repeatedly been invited to a neighbour's house, but she didn't trust her and refused to come along. "It later turned out that she'd killed and eaten twenty-two children in this way." A couple who lived nearby later accidentally revealed that they had murdered and eaten their own son, avoiding suspicions about his disappearance by claiming that he had gone to the countryside.[19] Another woman later remembered how she had once discovered "the body of a fifteen-year-old girl stowed under the stairwell of an apartment block. Bits of her body had been cut away", making her realize that the girl "had been killed for food." Many children disappeared for good; later only their clothes, and sometimes their bones, were found. The police kept a storeroom full of children's clothes, telling a mother missing a child: "If you find your daughter's underwear ... we can tell you where they killed her – and ate her."[20]

China

In China, a custom known as "exchanging one's children and eating them" was practised over thousands of years during times of hunger. Neighbouring families swapped one of their children, each family then slaughtering and eating the child of the other family, thus "alleviat[ing] their hunger" without having to eat their own family members. The oldest references to this tradition are from a siege in the 6th century BCE; the most recent ones from the Great Chinese Famine triggered by the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962).[21] It has also been recorded from various other famines in Chinese history, including other sieges, the Northern Chinese Famine of 1876–1879, and famines in the 1930s. Most of the victims were girls, since "boys were considered more valuable".[22]

Early accounts of the practice treat it as "a sign of determination rather than desperation", since it made cities "essentially impossible to starve out".[23] In the 1990s, survivors of the Great Chinese Famine told the journalist Jasper Becker that the deadly exchanges had been accepted as "a kind of hunger culture" driven by desperation.[24]

The same famine-induced custom of swapping one's children with those of others and then eating the other child has also been reported from Fiji, French Polynesia, and (with only daughters as victims) from among the Azande people in Central Africa.[25]

In other cases, children were kidnapped and eaten, and desperate parents sometimes killed and consumed their own children, both during the Great Chinese Famine and in various earlier famines.[21][26][27] Children whose parents had died or abandoned them were particularly at risk. A relief worker in the 1870s famine observed that such children "were slaughtered and eaten by other famine victims as though they were sheep or pigs". Since "meat has become more valuable than human life" for the starving, abandoned children could expect no mercy from those who soon discovered that they could be killed as easily as pigs, states another account from the famine.[28]

Accounts from earlier famines indicate that wealthy people sometimes purchased poor children when their starving parents had to sell them, and then used them as a source of meat. During a siege in the 9th century, "parents brought their children to butcher shops to sell them" for immediate processing.[29] Oral accounts from the 1870s famine as well as earlier famines also indicate that human flesh, usually from "young women and children", was served at inns to customers who preferred it to a meatless diet.[30]

Sometimes the flesh of butchered children was sold on markets.[31] During a famine induced by the fighting between the Jin and the Song dynasty in the 12th century, little children were praised for their "superior tastiness" and sold whole to those who wanted to prepare and serve them like suckling pigs or steamed whole lambs. Like the sale of human flesh at inns, such customs indicate that the consumption of such flesh also had a culinary side, even in times of famine.[32][33]

Infanticidal cannibalism

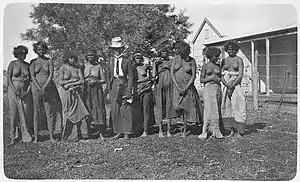

Infanticidal cannibalism or cannibalistic infanticide refers to cases where newborns or infants are killed because they are "considered unwanted or unfit to live" and then "consumed by the mother, father, both parents or close relatives".[34][35] Infanticide followed by cannibalism was practised in various regions, but is particularly well documented among Aboriginal Australians.[35][36][37] Among animals, such behaviour is called filial cannibalism, and it is common in many species, especially among fish.[38][39]

Before colonization, Aboriginal Australians were predominantly nomadic hunter-gatherers at times lacking in protein sources. Infanticide was widely practised as a means of population control and because mothers had trouble carrying two young children not yet able to walk, and various sources indicate that killed infants were often eaten.[40]

In the late 1920s, the anthropologist Géza Róheim heard from Aboriginals that infanticidal cannibalism had been practised especially during droughts. "Years ago it had been custom for every second child to be eaten" – the baby was roasted and consumed not only by the mother, but also by the older siblings, who benefited from this meat during times of food scarcity. One woman told him that her little sister had been roasted, but denied having eaten of her. Another "admitted having killed and eaten her small daughter", and several other people he talked to remembered having "eaten one of their brothers".[41] The consumption of infants took two different forms, depending on where it was practised:

When the Yumu, Pindupi, Ngali, or Nambutji were hungry, they ate small children with neither ceremonial nor animistic motives. Among the southern tribes, the Matuntara, Mularatara, or Pitjentara, every second child was eaten in the belief that the strength of the first child would be doubled by such a procedure.[42]

Usually only babies who had not yet received a name (which happened around the first birthday) were consumed, but in times of severe hunger, older children (up to four years or so) could be killed and eaten too, though people tended to have bad feelings about this. Babies were killed by their mother, while a bigger child "would be killed by the father by being beaten on the head".[43] But cases of women killing older children are on record too. In 1904 a parish priest in Broome, Western Australia, stated that infanticide was very common, including one case where a four-year-old was "killed and eaten by its mother", who later became a Christian.[44]

The journalist and anthropologist Daisy Bates, who spent a long time among Aboriginals and was well acquainted with their customs, knew an Aboriginal woman who one day left her village to give birth a mile away, taking only her daughter with her. She then "killed and ate the baby, sharing the food with the little daughter." After her return, Bates found the place and saw "the ashes of a fire" with the baby's "broken skull, and one or two charred bones" in them.[45] She states that "baby cannibalism was rife among these central-western peoples, as it is west of the border in Central Australia."[46]

The Norwegian ethnographer Carl Sofus Lumholtz confirms that infants were commonly killed and eaten especially in times of food scarcity. He notes that people spoke of such acts "as an everyday occurrence, and not at all as anything remarkable."[47]

In North Queensland in the 1880s, the prospector and explorer Christie Palmerston opened an oven in an abandoned Aboriginal camp, allured by a "fleshy smell", and found "a female child half roasted" inside. "The skull had been stove in, the whole of the inside cleaned out and refilled with red hot stones." He noted that in this area, young girls were most at risk of being killed and eaten, resulting in "female children being so scarce" compared to male ones. A man he talked to assured him that "a piccaninny makes quite a delicious meal – he had assisted in eating many".[48]

Some have interpreted the consumption of infants as a religious practice: "In parts of New South Wales ..., it was customary long ago for the first-born of every lubra [Aboriginal woman] to be eaten by the tribe, as part of a religious ceremony."[49] However, there seems to be no direct evidence that such acts actually had a religious meaning, and the Australian anthropologist Alfred William Howitt rejects the idea that the eaten were human sacrifices as "absolutely without foundation", arguing that religious sacrifices of any kind were unknown in Australia.[50]

Infanticide followed by cannibalism has also been documented for the Azande people in Central Africa, where twins were sometimes killed and eaten.[51]

Among the Wariʼ in the Brazilian rainforest, infanticide was rare, but cases occurred, especially of babies born to young unmarried girls. During the stress and chaos of the contact era, infanticide became more common – young orphans, sometimes already toddlers, were killed if there were no relatives or if the relatives found it impossible to care for them. Killed infants and toddlers were regarded as "nonpersons", and hence "cut up and roasted immediately" and then eaten in the same way as "animals and enemy outsiders" – this treatment signalled that the infant had been rejected as a kin and person.[52]

Consumption of slave children

Sumatra

According to the 14th century traveller Odoric of Pordenone, the inhabitants of Lamuri, a kingdom in northern Sumatra, purchased children from foreign merchants to "slaughter them in the shambles and eat them". Odoric states that the kingdom was wealthy and there was no lack of other food, suggesting that the custom was driven by a preference for human flesh rather than by hunger.[53] He shows excellent knowledge of Sumatra, indicating that he had really been there, and several other sources confirm that cannibalism was practised in northern Sumatra around that time. The merchants, though likely not cannibals themselves, apparently had no scruples selling slave children for the "shambles".[54] Odoric's account was later borrowed by John Mandeville for his Book of Marvels and Travels.[55]

The Congo Basin

Up to the late nineteenth century, cannibalism was practised widely in the some parts of the Congo Basin, with slaves being frequent victims. Many "healthy children" had to die "to provide a feast for their owners".[56] Young slave children were at particular risk since they were in low demand for other purposes and since their flesh was widely praised as especially delicious, "just as many modern meat eaters prefer lamb over mutton and veal over beef".[57] Some people fattened slave children to sell them for consumption; if such a child became ill and lost too much weight, their owner drowned them in the nearest river instead of wasting further food on them, as the French missionary Prosper Philippe Augouard once witnessed.[58]

Various reports from the late 19th century indicate that around the Ubangi River in the north of the Congo Basin, slaves were frequently exchanged against ivory, which was then exported to Europe or the Americas, while the slaves were eaten.[59] The local elephant hunters preferred the flesh especially of young human beings – four to sixteen was the preferred age range, according to one trader – "because it was not only more tender, but also much quicker to cook" than the meat of elephants or other large animals.[60] Sometimes ten or more purchased children were butchered and consumed in a single event in the vicinity of the Catholic mission station erected in today's Bangui.[61]

In order a ensure a regular supply, "the chiefs raise herds of [children], like we do with sheep or geese at home", stated a missionary after a trip along the Ubangi.[62] Several accounts indicate that children were indeed fattened and slaughtered on a regular basis. While one or two victims per village and week seem to have been typical, Augouard also mentions "a village which I know well, [where] a child aged ten to twelve was sacrificed every day to serve as food for the chief and the principals of the area," thus also indicating that the regular enjoyment of such dishes was a privilege of the influential and well-connected.[63] The killing of slave children for culinary purposes is also documented for various other parts of the Congo Basin, including the north and northeast,[64] the eastern Maniema region,[65] and the Kasai region in the south.[66]

Slave raiding and cannibalism often went hand in hand, as those killed in fighting and those who were too young, too old, or otherwise considered less suitable for sale, were often eaten right after a slave raid, or otherwise sold to nearby cannibals for consumption.[67] The German ethnologist Leo Frobenius recorded that young children caught in raids were "skewered on long spears like rats and roasted over a quickly kindled large fire", while older captives were kept alive to be exploited or sold as slaves.[64] In 1863, the English explorer Samuel Baker talked with a member of a Swahili–Arab raiding party, who told him that their local Azande allies routinely killed and ate the children captured in raids:

Their custom was to catch a child by its ankles, and to dash its head against the ground; thus killed, they opened the abdomen, extracted the stomach and intestines, and tying the two ankles to the neck they carried the body by slinging it over the shoulder, and thus returned to camp, where they divided it by quartering, and boiled it in a large pot.[68][69]

Another man told Baker that at Gondokoro, where they were at that time, he had once seen how several slave children were slaughtered and then served at "a great feast" held by the Azande members of a slave raiding party.[70][71]

Children born to enslaved mothers could meet the same fate. The German ethnologist Georg A. Schweinfurth once saw a newborn baby among the ingredients assembled for a meal. He learned that the baby, whose mother was a slave, would soon be "cooked together with the gourds", since capturing slaves was more convenient than raising them from birth. He also heard persistent rumours that little slave children were frequently served at the table of the Azande king.[72]

Generally, slaves and their flesh were not expensive in the Congo region. In some areas, human flesh was up to twice as expensive as that of animals, while elsewhere the prices of both were comparable.[73] Accordingly, a girl of six or ten years could be purchased for the price of a dwarf goat, or sometimes even cheaper,[74] and people do not seem to have regarded the consumption of one as more morally troubling than the consumption of the other, though they generally preferred the taste of the child.[75][76] Missionaries observed that a living slave child was nevertheless "worth less than a quarter of a hippopotamus or of a buffalo", due to the much smaller amount of meat which the child would yield.[77]

Sometimes white men played a role in the death of Congolese slave children. In a case that shocked the European and American press, the Scot James Jameson, a member of Henry Morton Stanley's last expedition, apparently paid the purchase price of a 10-year-old girl and then watched and made drawings while she was stabbed, dismembered, cooked, and eaten in front of him. Jameson defended himself by claiming that he had considered the whole affair a joke and had not thought the child would really die until it was too late.[78][79][80]

Other cases received little or no international attention. At about the same time as the Jameson affair, in the late 1880s, a white trader accidentally caused the death of a slave boy whom he had rented from a Bangala head man. When he complained about the boy's unreliability, the man reacted by killing the boy "with a thrust of his spear", and one day later his teenage son "nonchalantly remarked that – 'That slave boy was very good eating – he was nice and fat.'"[81][82] According to Herbert Ward, who witnessed and documented the incident, "the pot" was the usual destination of any slave who annoyed or disappointed their owner, and "light repast[s] off the limbs of some unfortunate slave, slain for refractory behavior", were served in the area on an fairly regular basis. The relations between the locals and the white men at the trading post were nevertheless, "as a rule, friendly".[83]

While travelling along the Ubangi River, the French explorer Maurice Musy declined an opportunity to purchase a young slave girl, though there was "human meat" cooking in pots around them and he was well aware that the local demand for children her age was largely cannibalistic (indeed she might have been offered to his party as provisions). "Maybe at this hour she is being eaten. That is very likely", he commented in a diary-style letter.[84] His colleague Albert Dolisie was more generous when he met in the same region a young slave boy who, "trembling all over and deeply ashamed", explained that he was destined to be beheaded and eaten soon. Dolisie approached the boy's owner who finally agreed to hand the boy over to him.[85]

Angola and West Africa

There are also reports of the consumption of young slaves and victims of slave raids from other parts of Central and Western Africa. Around the Cuanza River in today's Angola, children caught in raids but too young to be profitably sold as slaves were butchered in public, their fresh flesh then sold to passers-by, according to the Hungarian explorer László Magyar, who states that he repeatedly saw such scenes himself.[86] In regions that today belong to Nigeria, the baked bodies of deliberately fattened slave children were served as delicacies, as young children's flesh was said to be "the best [food] of all".[87] Oral accounts indicate that around the beginning of the 20th century, children playing outside were still at risk of "being kidnapped and either killed and eaten or sold away or sacrificed to one god or the other."[88]

Cannibalistic child murderers

Various cases of adult men – often serial killers – murdering and eating children have been recorded throughout newer history, especially in the 20th century. In the United States in the 1920s, Albert Fish killed at least three children, afterwards roasting and eating their flesh. "How sweet and tender her little ass was roasted in the oven", he wrote about one of his victims, 10-year-old Grace Budd.[89]

In the 1990s, Nathaniel Bar-Jonah seems to have killed and consumed at least one boy, though further child victims are suspected. The body of his 10-year-old victim was never found, but after the boy's disappearance Bar-Jonah apparently did not buy any groceries for a month. At the same time he held a number of cookouts, at which he served burgers and other meat dishes to his guests, several of whom found that the meat "tasted strange". He told one of his guests that it came from a deer which he had personally "hunted, killed, [and] butchered". After his arrest, a number of recipes using children's body parts were found in his apartment, plus notes indicating that he had actually cooked some of these dishes for his neighbours.[90][91]

.jpg.webp)

In Germany, Fritz Haarmann, also called the "Butcher of Hanover", sexually assaulted and murdered at least 24 boys, most of them teenagers, between 1918 and 1924. He regularly sold boneless ground meat on the black market and gave different and contradictory explanations about the origin of this meat. Suspicions that this was his way of getting rid of some of the mortal remains of his victims were never definitively confirmed, nor refuted.[92]

Between the 1950s and 1970s, Joachim Kroll, nicknamed the "Ruhr Cannibal", murdered probably more than a dozen women and girls. Most of his victims were girls from 4 to 16 years of age, and he usually raped them before strangling them. When he was arrested, parts of the body of 4-year-old Marion Ketter, his last victim, were in his freezer, while a small hand was cooking in a pan of boiling water.[93]

In the Soviet Union, Andrei Chikatilo sexually assaulted and murdered more than 50 women and children between 1978 and 1990. His first victim was a 9-year-old girl and most of his victims were boys and girls, some as young as 7. Over time, he "started cutting off boys' genitals and excising the uterus from his female victims, chewing and eating them to attain new heights of sexual pleasure." The police also found evidence suggesting that he had roasted body parts of his victims on campfires. Many of the murdered were runaways or vagrants, and he motivated his acts as due to "his disgust at these kinds of people [who were] always pestering people".[94]

While these and similar cases were generally committed by men and motivated, at least in part, by sexual sadism, an unusual case was committed by a couple and apparently motivated by hunger. During a severe famine in Iraq in 1917, Abboud and Khajawa murdered more than a hundred young children in order to cook and eat or sell their flesh. The couple deliberately targeted children because they found their flesh to be much tastier than of their first victim, an elderly woman.[95]

Recent cases

Fetus eating in China

In the mid-1990s, Hong Kong journalists exposed "an underground market in human foetuses" in both Mainland China and Hong Kong. Traders connected to hospitals sold aborted fetuses for consumption, charging "up to $300 apiece" and promising "all sorts of medical benefits ... from rejuvenation to a cure for asthma".[96] While recovering from an accident, the director Fruit Chan was repeatedly served an "'exceptional' soup" by his doctor, finding out only later that it was "made of fetus". Chan and the screenwriter Lilian Lee believe that they also unknowingly ate such soup while researching in hospitals for their movie Dumplings (2004), which features this custom.[97]

Possibly inspired by reports of this custom, the Chinese performance artist Zhu Yu cooked and ate what he claimed to be a human fetus in a controversial piece of conceptual art. His performance entitled "Eating People" took place at a Shanghai arts festival in 2000. When pictures of it begin to circulate on the Internet one year later, both the FBI and Scotland Yard started investigations into the matter.[98][99][100] Zhu claimed that "no religion forbids cannibalism, nor can I find any law which prevents us from eating people", and said that he "took advantage of the space between morality and the law", publicly performing an act that is widely considered immoral but not actually illegal.[98] The work has been interpreted as "shock art".[100][101][102]

Whether Zhu ate an actual fetus is unclear.[98] Zhu himself claims to have cooked and eaten a six-month-old aborted fetus stolen from a medical school,[99][100] but others maintain that the "fetus" might have been a prop, possibly constructed by placing a doll's head on a duck carcass.[98][103][104] Other images of another art exhibit were circulated along with Zhu Yu's photographs and falsely claimed to be evidence of fetus soup.[105]

In 2011/2012, more than 17,000 capsule pills purported to be filled with the powdered flesh of human fetuses or stillborns and "touted for increasing vitality and sex drive" were seized by South Korean customs officials from ethnic Koreans living in China, who had tried to bring them into South Korea in order to consume the capsules themselves or distribute them to others.[106][107][108] Some experts later suggested that the pills may actually have been made of human placenta, as placentophagy is a legal and relatively widespread practice in China.[109][110]

Critics see the spreading of unverified or mislabelled accounts of fetus eating as a form of blood libel – wrongly accusing one's enemy of killing or eating children – and blame members of the US Congress for using mere rumours as a political lever.[111][104]

Famines in North Korea

Various reports of cannibalism began to emerge from North Korea during a severe famine in the mid-1990s. In 1998, several refugees reported that children in their neighbourhood had fallen victim to this custom. One told that "his neighbors [had eaten] their daughter", another knew a woman who had eaten "her 2-year-old child", and a third said that "her neighbor killed, salted and ate an uncared-for orphan".[112] According to other refugees interviewed by the journalist Jasper Becker, similar acts were by no means rare. A former soldier told him that starving parents "kill and eat their own infants ... in many places". Other parents sold or abandoned their children, and the fate of parentless children was often dire. Becker heard of a "couple ... executed for murdering 50 children" and selling their flesh, "mixed with pork", in the market. Another executed woman was accused of having killed 18 children for food, and a whole "family of five" was executed "for luring small children into their house, drugging them, [and] chopping up their bodies" for consumption.[113]

Episodes of famine that sometimes led to cannibalism continued into the new millennium. In 2012 it became known that three years earlier "a man was executed in Hyesan ... for killing a girl and eating her ... after supplies to the city dwindled" due to unsuccessful government attempts at currency reform.[114] A few months later, reports of "citizen journalists" indicated that "a 'hidden famine' in the farming provinces of North and South Hwanghae has killed 10,000 people" and driven some to cannibal acts. One informant told: "In my village in May, a man who killed his own two children and tried to eat them was executed by a firing squad." Others stated that "some men boiled their children before eating them" – even an official of the ruling Workers' Party confirmed one such case.[115]

Satire

Jonathan Swift's 1729 satiric article "A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People in Ireland from Being a Burden to Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Public" proposed the utilization of an economic system based on poor people selling their children to be eaten, claiming that this would benefit the economy, family values, and general happiness of Ireland. The target of Swift's satire is the rationalism of modern economics, and the growth of rationalistic modes of thinking at the expense of more traditional human values.

In popular culture

Novels and short stories

The main part of Robert A. Heinlein's science fiction novel Farnham's Freehold (1964) is set in a distant future where, long after much of the northern hemisphere was devastated in a full-scale nuclear war, a dark-skinned ruling class (descendants of the Africans, Arabs, and Hindus of today) exploits white-skinned people as slaves, including sexually.[116] White children are bred on ranches for consumption and slaughtered at around 12 to 14 years of age (when their flesh is considered particularly tasty) or sometimes already as babies. Boys are often castrated several years before their death, as that is thought to improve the quality of their meat.[117] Despite being apparently anti-racist in intent (Heinlein had wanted his white readers to think about how belonging to an exploited and despised minority would feel like), the novel was widely criticized for its racial stereotyping.[118][119]

Donald Kingsbury's science fiction novel Courtship Rite (1982) takes place in a society of settlers whose ancestors arrived, centuries ago, on a planet whose own plants and animals have a biochemistry utterly different from that on Earth, rendering them poisonous to the settlers. The humans can therefore eat only the few plant species they brought from Earth, and as they brought no animals, they have turned to cannibalism in order to get meat. Children are taken from their parents immediately after birth and submitted to a highly competitive selection process while being raised in public "crèches". Those who fail any of the multiple tests are "culled" and butchered, their flesh then sold as food. Throughout the novel, the consumption of this human flesh is treated as a normal and uncontroversial act, deeply ingrained into the fabric of life and not a matter of ethical concern.

In Mo Yan's satirical novel The Republic of Wine (1992), roasted baby boys, called "meat boys" or "braised babies", are served whole as gourmet dishes in a fictional Chinese province called Liquorland. The book has been read as criticizing the increasing disparities in wealth and status in Chinese society, where the "pleasure and desire for delicacies" of the wealthy matter more than the lives of the poor, until "the inferior in social rank becomes food" in the novel's satirical exaggeration.[120] It is also a criticism of the increasing commodification after China's turn to capitalism. In the novel, the inventor of the "braised baby" argues that "the babies we are about to slaughter and cook are small animals in human form that are, based upon strict, mutual agreement, produced to meet the special needs of Liquorland's developing economy and prosperity", not essentially different from other animals raised for consumption or other goods produced for sale. If anything can become a commodity based on the mutual consent of buyer and seller, then Liquorland's cannibalism is just the logical consequence.[121]

In Vladimir Sorokin's short story "Nastya" (2000), a girl who has just turned 16 is cooked whole in an oven and eaten by her family and their friends, including an Orthodox priest. According to the story, which is set around the year 1900[122] in an alternative Russian Empire, "a lot of people get cooked". Indeed the celebrating families already plan the death of Nastya's friend Arina, who will be put into the oven in a few months (alive, as usual). The girls, though fearful, generally seem to submit willingly, not wanting to violate family traditions.[123] Ignoring the dark story's satirical character, pro-Kremlin activists accused Sorokin of "promoting cannibalism" and "degrad[ing] people's Russian Orthodox heritage".[124]

In Cormac McCarthy's post-apocalyptic novel The Road (2006), the protagonists find an abandoned campsite with a newborn infant roasted on a spit.

Movies

In the spy comedy Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (1999), the character Fat Bastard boasts of having once eaten a baby and later tries to eat a person with dwarfism because "he kinda looks like a baby".

In Fruit Chan's film Dumplings (2004), aborted fetuses are eaten by wealthy people because they are believed to have rejuvenating properties. The film has been called "one of the most realistic works of 'fiction'", since it deals with a practice that has been repeatedly reported from China's and Hong Kong's recent past.[125] Indeed the director Fruit Chan and the screenwriter Lilian Lee believe that they were served fetus soup while researching for the film in a hospital and that Chan repeatedly consumed such soup while recovering after an accident, finding out only afterwards that "he had eaten soup made from a miscarried five-month fetus".[126] The film has been interpreted as a criticism of China's one-child policy, which caused many parents to have abortions even against their will. It raises the question of who is more to blame: the government whose policy makes sure that the fetuses cannot be born, or those who then exploit their bodies for their own purposes?[127]

See also

- Child sacrifice – the sacrifice (and sometimes consumption) of children in religious contexts

- Filial cannibalism – adult animals consuming young members of their own species

- Human placentophagy – the consumption of the placenta after birth

- Kindlifresserbrunnen – a Swiss fountain which depicts a child eater

- Saturn Devouring His Son – a famous painting by Francisco Goya (along with similar paintings which were made by other artists)

- Traditional Chinese medicines derived from the human body – among them are human flesh and children's bones

References

- ↑ Ferguson, George (1976) [1954]. "St. Nicholas of Myra or Bari". Signs and Symbols in Christian Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 136.

- ↑ Heiner, Heidi Anne (16 April 2008). "Buttercup". SurLaLune Fairy Tales: The Fairy Tales of Asbjørnsen and Moe. Archived from the original on 5 April 2014.

- ↑ Jacobs, Joseph (1890). . – via Wikisource.

- ↑ Barnett, David (21 November 2022). "Baba Yaga: The greatest 'wicked witch' of all?". BBC Culture. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ↑ Kelly, John (2005). The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time. New York: HarperCollins. p. 242.

- ↑ Ben Zion, Ilan (16 August 2012). "Saudi cleric accuses Jewish people of genocide, drinking human blood". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ↑ Benari, Elad (17 June 2013). "Egyptian Politician: Jews Use Blood for Matzos". Israel National News. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ↑ Ellerbe, Helen (1995). The Dark Side of Christian History. Morningstar & Lark.

- ↑ Stone, Lillian (12 March 2021). "A not-so-brief history of witches cooking and eating children". The Takeout. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ↑ Bibby, Peter C (1996). Organised Abuse: The Current Debate. Aldershot, England: Arena. pp. 205–213. ISBN 978-1-85742-284-9.

- ↑ Frankfurter, D (2006). Evil Incarnate: Rumors of Demonic Conspiracy and Ritual Abuse in History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 123, 127. ISBN 978-0-691-11350-0.

- 1 2 Applebaum, Anne (2017). Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine. London: Penguin. chapter 11.

- ↑ Siefkes, Christian (2022). Edible People: The Historical Consumption of Slaves and Foreigners and the Cannibalistic Trade in Human Flesh. New York: Berghahn. pp. 255, 257. ISBN 978-1-80073-613-9.

- ↑ Kindler, Robert (2018). Stalin's Nomads: Power and Famine in Kazakhstan. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-8229-8614-0.

- ↑ Chong, Key Ray (1990). Cannibalism in China. Wakefield, NH: Longwood. p. 55.

- ↑ Figes, Orlando (1997). A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924. London: Pimlico. pp. 777–778.

- ↑ Figes quoted in Korn, Daniel; Radice, Mark; Hawes, Charlie (2001). Cannibal: The History of the People-Eaters. London: Channel 4 Books. p. 81.

- ↑ Kindler 2018, p. 168.

- ↑ Korn, Radice & Hawes 2001, p. 85.

- ↑ Jones, Michael (2008). Leningrad: State of Siege. London: John Murray. chapter 7.

- 1 2 Becker, Jasper (1996). Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine. London: John Murray. chapter 14.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 251–252.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 264.

- ↑ Becker 1996, chapter 9.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 252–253.

- ↑ Edgerton-Tarpley, Kathryn (2008). Tears from Iron. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 212–213, 217, 219, 224.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 253–257.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 254.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 255.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 259.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 257.

- ↑ Chong 1990, p. 137.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 258–260.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 14.

- 1 2 Travis-Henikoff, Carole A. (2008). Dinner with a Cannibal: The Complete History of Mankind's Oldest Taboo. Santa Monica: Santa Monica Press. p. 196.

- ↑ Bates, Daisy (1938). The Passing of the Aborigines. London: John Murray. chs. 10, 17.

- ↑ Róheim, Géza (1976). Children of the Desert: The Western Tribes of Central Australia. Vol. 1. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 69, 71–72.

- ↑ Bose, Aneesh P. H. (2022). "Parent–Offspring Cannibalism throughout the Animal Kingdom: A Review of Adaptive Hypotheses". Biological Reviews. 97 (5): 1868–1885. doi:10.1111/brv.12868. ISSN 1464-7931. PMID 35748275. S2CID 249989939.

- ↑ Forbes, Scott (2005). A Natural History of Families. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-4008-3723-6.

- ↑ Howitt, A. W. [Alfred William] (1904). The Native Tribes of South-East Australia. London: Macmillan. pp. 748–750.

- ↑ Róheim 1976, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Róheim 1976, p. 71.

- ↑ Róheim 1976, pp. 69, 72.

- ↑ Royal Commission on the Conditions of the Natives (1905). Report Presented to Both Houses of Parliament. Perth: Wm. Alfred Watson. pp. 61, 63.

- ↑ Bates 1938, ch. 17.

- ↑ Bates 1938, ch. 10.

- ↑ Lumholtz, Carl (1889). Among Cannibals: An Account of Four Years' Travels in Australia and of Camp Life with the Aborigines of Queensland. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 134, 254, 273.

- ↑ Woolston, F. P.; Colliver, F. S. (1968). "Christie Palmerston: A North Queensland Pioneer, Prospector and Explorer". Queensland Heritage. 1 (8): 29. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ↑ Smith, R. Brough (1878). The Aborigines of Victoria. Vol. 1.

- ↑ Howitt 1904, pp. 754–756.

- ↑ Gero, F. Cannibalism in Zandeland: Truth and Falsehood. Bologna: Editrice Missionaria Italiana. pp. 45–46, 67.

- ↑ Conklin, Beth A. (2001). Consuming Grief: Compassionate Cannibalism in an Amazonian Society. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 128–130. ISBN 0-292-71232-4.

- ↑ Henry Yule, ed. (1866). Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Issue 36. pp. 84–86.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 49.

- ↑ John Mandeville (2012). The Book of Marvels and Travels. Translated by Anthony Bale. Oxford University Press. pp. 78–79, 82. ISBN 978-0-19-960060-1.

- ↑ Edgerton, Robert B. (2002). The Troubled Heart of Africa: A History of the Congo. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 108.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 97.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 113.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 52–58.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 114, 125.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 56.

- ↑ P. Allaire quoted in Witte, Jehan de (1924). Monseigneur Prosper Philippe Augouard, Archevêque titulaire de Cassiopée, Vicaire apostolique du Congo français. Paris: Emile-Paul. pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 95.

- 1 2 Siefkes 2022, p. 64.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 137–138, 152–156.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 99, 115.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 58–66.

- ↑ Baker, Samuel White (1866). The Albert Nyanza, Great Basin of the Nile, and Explorations of the Nile Sources. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott. pp. 278–279.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 71.

- ↑ Baker 1866, pp. 279–280.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 121–124.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 62, 64, 91–93, 96–100, 125, 142.

- ↑ Edgerton 2002, pp. 86–88, 108–109.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 115.

- ↑ Edgerton 2002, pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Jeal, Tim (2007). Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 357–358.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 151–162.

- ↑ Ward, Herbert (1891). Five Years with the Congo Cannibals. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 136.

- ↑ Ward 1891, pp. 132–134.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 119.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, p. 104.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 233–234.

- ↑ Siefkes 2022, pp. 62.

- ↑ Isichei, Elizabeth (1977). Igbo Worlds: An Anthology of Oral Histories and Historical Descriptions. London: Macmillan. p. 111.

- ↑ "Albert Fish, Chapter 9: A Letter From Hell". Crime Library. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ↑ "Cannibalism and the Strange Case of Nathaniel Bar-Jonah". True Crime XL. 10 August 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ↑ Espy, John C. (2014). Eat the Evidence: A Journey Through the Dark Boroughs of a Paedophilic Cannibal's Mind. Karnac. ISBN 978-1-78220-033-8.

- ↑ Theodor, Lessing (1993). Monsters of Weimar. Nemesis. pp. 54, 60, 81. ISBN 1-897743-10-6.

- ↑ Francesconi, Claudio (1 July 2018). "Joachim Kroll, the Cannibal Serial Killer from Germany". Horror Galore. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ↑ Korn, Radice & Hawes 2001, p. 156.

- ↑ Riyad, Hany (20 October 2016). "الموصل قبل قرن .. سفاح ذبح مائة طفل وأكل لحومهم" [Mosul a century ago...A thug who slaughtered 100 children and ate their flesh]. Al-Ain (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 29 May 2023.

- ↑ Korn, Radice & Hawes 2001, p. 93.

- ↑ Tsai, Yun-Chu (2016). You Are Whom You Eat: Cannibalism in Contemporary Chinese Fiction and Film (PhD). UC Irvine. pp. 110, 132.

- 1 2 3 4 Mikkelson, Barbara (19 June 2001). "Fact Check: Are Human Fetuses 'Taiwan's Hottest Dish'?". Snopes. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- 1 2 "Baby-eating photos are part of Chinese artist's performance". Taipei Times. 23 March 2001. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 Rojas, Carlos (2002). "Cannibalism and the Chinese Body Politic: Hermeneutics and Violence in Cross-Cultural Perception". Postmodern Culture. 12 (3). doi:10.1353/pmc.2002.0025. S2CID 143485152. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ↑ Berghuis, Thomas J. (2006). Performance Art in China. Timezone 8 Limited. p. 163. ISBN 978-988-99265-9-5.

- ↑ Davis, Edward Lawrence (2005). Encyclopedia of Contemporary Chinese Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 729. ISBN 978-0-415-77716-2.

- ↑ Damarla, Prashanth (10 July 2014). "Chinese Eat Baby Soup for Sex – Facts Analysis". Hoax or Fact. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ↑ Chino (30 April 2015). "The Truth Behind The Viral Photo Of A Chinese Man Eating Fetus". Wereblog. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ↑ James, Susan Donaldson (7 May 2012). "Chinese-Made Infant Flesh Capsules Seized in S. Korea". ABC News. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ↑ "Pills filled with powdered human baby flesh found by customs officials". The Telegraph. 7 May 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ↑ "S Korea cracks down on 'human flesh capsules'". Al Jazeera. 7 May 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ↑ Savadove, Bill (25 June 2012). "Eating placenta, an age-old practice in China". Inquirer Lifestyle. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ↑ Selander, Jodi (3 July 2012). "Placenta in Demand, Creating a Black Market in China". Placenta Benefits. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ↑ Dixon, Poppy (October 2000). "Eating Fetuses: The lurid Christian fantasy of godless Chinese eating "unborn children."". Archived from the original on 13 March 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ↑ "French aid workers report cannibalism in famine-stricken North Korea". Minnesota Daily. 16 April 1998. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ↑ Becker, Jasper (2005). Rogue Regime: Kim Jong Il and the Looming Threat of North Korea. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-19-803810-8.

- ↑ "North Korea 'executes three people found guilty of cannibalism'". The Telegraph. 11 May 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ↑ "North Korean cannibalism fears amid claims starving people forced to desperate measures". The Independent. 28 January 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ↑ Heinlein, Robert A. (1964). Farnham's Freehold. New York: Putnam. chapters 13–14.

- ↑ Heinlein 1964, chapters 18, 20, 22.

- ↑ Darlage, Dale (2011). "Farnham's Freehold: A review". SF Site. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ↑ Heer, Jeet (9 June 2014). "A Famous Science Fiction Writer's Descent Into Libertarian Madness". The New Republic. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ↑ Tsai 2016, pp. 74, 97.

- ↑ Tsai 2016, p. 72.

- ↑ Nastya's father states that it's "only six months until the beginning of the twentieth century".

- ↑ Sorokin, Vladimir (December 2022). "Nastya". The Baffler (66). Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ↑ "Dissident Author Sorokin Accused of 'Promoting Cannibalism' in Work". The Moscow Times. 23 August 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ↑ Tsai 2016, p. 110.

- ↑ Tsai 2016, p. 132.

- ↑ Tsai 2016, p. 134.

External links

- Photos of Zhu Yu's performance in a South Korean newspaper (accompanied by a letter which claims them to be of an actual practice)

- News article from 2006 reporting that supposedly "cooked" body parts of children had not actually been cooked

- Fact Check: Are Human Fetuses 'Taiwan's Hottest Dish'?