| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

Fiat money is a type of currency that is not backed by a commodity, such as gold or silver. It is typically designated by the issuing government to be legal tender, and is authorized by government regulation. Since the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, the major currencies in the world are fiat money.

Fiat money generally does not have intrinsic value and does not have use value. It has value only because the individuals who use it as a unit of account – or, in the case of currency, a medium of exchange – agree on its value.[1] They trust that it will be accepted by merchants and other people as a means of payment for liabilities.

Fiat money is an alternative to commodity money, which is a currency that has intrinsic value because it contains, for example, a precious metal such as gold or silver which is embedded in the coin. Fiat also differs from representative money, which is money that has intrinsic value because it is backed by and can be converted into a precious metal or another commodity. Fiat money can look similar to representative money (such as paper bills), but the former has no backing, while the latter represents a claim on a commodity (which can be redeemed to a greater or lesser extent).[2][3][lower-alpha 1]

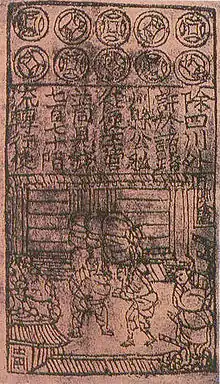

Government-issued fiat money banknotes were used first during the 13th century in China.[4] Fiat money started to predominate during the 20th century. Since President Richard Nixon's decision to suspend US dollar convertibility to gold in 1971, a system of national fiat currencies has been used globally.

Fiat money can be:

- Any money that is not backed by a commodity.

- Money declared by a person, institution or government to be legal tender,[5] meaning that it must be accepted in payment of a debt in specific circumstances.[6]

- State-issued money which is neither convertible through a central bank to anything else nor fixed in value in terms of any objective standard.[7]

- Money used because of government decree.[2]

- An otherwise non-valuable object that serves as a medium of exchange[8] (also known as fiduciary money).[9]

The term fiat derives from the Latin word fiat, meaning "let it be done"[lower-alpha 2] used in the sense of an order, decree[2] or resolution.

Treatment in economics

Most of the money in the economy is created, not by printing presses at the central bank, but by banks when they provide loans. [...] This also means as you pay off the loan, the electronic money your bank created is 'deleted' – it no longer exists. So essentially, banks create money, not wealth.[10]

In monetary economics, fiat money is an intrinsically valueless object or record that is accepted widely as a means of payment.[1] Accordingly, the value of fiat money is greater than the value of its metal or paper content.

One justification for fiat money comes from a micro-founded model. In most economic models, agents are intrinsically happier when they have more money. In a model by Lagos and Wright, fiat money does not have an intrinsic worth but agents get more of the goods they want when they trade assuming fiat money is valuable. Fiat money's value is created internally by the community and, at equilibrium, makes otherwise infeasible trades possible.[11]

In the Grundrisse, Karl Marx was among the first to consider the modern economic ramifications of a historical switch to fiat money from the gold or silver-commodity. Marx writes:

"Suppose that the Bank of France did not rest on a metallic base, and that other countries were willing to accept the French currency or its capital in any form, not only in the specific form of the precious metals. Would the bank not have been equally forced to raise the terms of its discounting precisely at the moment when its "public" clamoured most eagerly for its services? The notes with which it discounts the bills of exchange of this public are at present nothing more than drafts on gold and silver. In our hypothetical case, they would be drafts on the nation’s stock of products and on its directly employable labour force: the former is limited, the latter can be increased only within very positive limits, and in certain amounts of time. The printing press, on the other hand, is inexhaustible and works like a stroke of magic."

Commenting on the passage, economist and geographer David Harvey writes that "[t]he consequence, as Marx saw it, would be that "the directly exchangeable wealth of the nation" would be ‘absolutely diminished’ alongside of ‘an unlimited increase of bank drafts’ (i.e., accelerating indebtedness) with the direct consequence of ‘increase in the price of products, raw materials and labour’ (inflation) alongside a ‘decrease in price of bank drafts’ (ever-falling rates of interest)." Harvey notes the accuracy of the modern economy in this way, save for "…the rising prices of labor and means of production (low inflation except for assets such as stocks and shares, land and property and resources such as water rights)."[12] The latter point can be explained by the private exportation of debt,[13] labour, and figurative and/or literal waste[14] to the global periphery, a concept related to metabolic and carbon rift.

Another mathematical model that explains the value of fiat money comes from game theory. In a game where agents produce and trade objects, there can be multiple Nash equilibria where agents settle on stable behavior. In a model by Kiyotaki and Wright, an object with no intrinsic worth can have value during trade in one (or more) of the Nash Equilibria.[15]

History

China

China has a long history with paper money, beginning in the 7th century CE. During the 11th century, the government established a monopoly on its issuance, and about the end of the 12th century, convertibility was suspended.[16] The use of such money became widespread during the subsequent Yuan and Ming dynasties.[17]

The Song Dynasty in China was the first to issue paper money, jiaozi, about the 10th century CE. Although the notes were valued at a certain exchange rate for gold, silver, or silk, conversion was never allowed in practice. The notes were initially to be redeemed after three years' service, to be replaced by new notes for a 3% service charge, but, as more of them were printed without notes being retired, inflation became evident. The government made several attempts to maintain the value of the paper money by demanding taxes partly in currency and making other laws, but the damage had been done, and the notes became disfavored.[18]

The succeeding Yuan Dynasty was the first dynasty of China to use paper currency as the predominant circulating medium. The founder of the Yuan Dynasty, Kublai Khan, issued paper money known as Jiaochao during his reign. The original notes during the Yuan Dynasty were restricted in area and duration as in the Song Dynasty.

During the 13th century, Marco Polo described the fiat money of the Yuan Dynasty in his book The Travels of Marco Polo:[19][20]

All these pieces of paper are issued with as much solemnity and authority as if they were of pure gold or silver... and indeed everybody takes them readily, for wheresoever a person may go throughout the Great Kaan's dominions he shall find these pieces of paper current, and shall be able to transact all sales and purchases of goods by means of them just as well as if they were coins of pure gold.

— Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo

Europe

Washington Irving records an emergency use of paper money by the Spanish for a siege during the Conquest of Granada (1482–1492). In 1661, Johan Palmstruch issued the first regular paper money in the West, by royal charter from the Kingdom of Sweden, through a new institution, the Bank of Stockholm. While this private paper currency was largely a failure, the Swedish parliament eventually assumed control of the issue of paper money in the country. By 1745, its paper money was inconvertible to specie, but acceptance was mandated by the government.[21] This fiat currency depreciated so rapidly that by 1776 it was returned to a silver standard. Fiat money also has other beginnings in 17th-century Europe, having been introduced by the Bank of Amsterdam in 1683.[22]

New France 1685–1770

In 17th century New France, now part of Canada, the universally accepted medium of exchange was the beaver pelt. As the colony expanded, coins from France came to be used widely, but there was usually a shortage of French coins. In 1685, the colonial authorities in New France found themselves seriously short of money. A military expedition against the Iroquois had gone badly and tax revenues were down, reducing government money reserves. Typically, when short of funds, the government would simply delay paying merchants for purchases, but it was not safe to delay payment to soldiers due to the risk of mutiny.

Jacques de Meulles, the Intendant of Finance, conceived an ingenious ad hoc solution – the temporary issuance of paper money to pay the soldiers, in the form of playing cards. He confiscated all the playing cards in the colony, had them cut into pieces, wrote denominations on the pieces, signed them, and issued them to the soldiers as pay in lieu of gold and silver. Because of the chronic shortages of money of all types in the colonies, these cards were accepted readily by merchants and the public and circulated freely at face value. It was intended to be purely a temporary expedient, and it was not until years later that its role as a medium of exchange was recognized. The first issue of playing card money occurred during June 1685 and was redeemed three months later. However, the shortages of coinage reoccurred and more issues of card money were made during subsequent years. Because of their wide acceptance as money and the general shortage of money in the colony, many of the playing cards were not redeemed but continued to circulate, acting as a useful substitute for scarce gold and silver coins from France. Eventually, the Governor of New France acknowledged their useful role as a circulating medium of exchange.[23]

As the finances of the French government deteriorated because of European wars, it reduced its financial assistance to its colonies, so the colonial authorities in Canada relied more and more on card money. By 1757, the government had discontinued all payments in coin and payments were made in paper instead. In an application of Gresham’s Law – bad money drives out good – people hoarded gold and silver, and used paper money instead. The costs of the Seven Years' War resulted in rapid inflation in New France. After the British conquest in 1760, the paper money became almost worthless, but business did not end because gold and silver that had been hoarded came back into circulation. By the Treaty of Paris (1763), the French government agreed to convert the outstanding card money into debentures, but with the French government essentially bankrupt, these bonds were defaulted and by 1771 they were worthless.

The Royal Canadian Mint still issues Playing Card Money in commemoration of its history, but now in 92.5% silver form with gold plate on the edge. It therefore has an intrinsic value which considerably exceeds its fiat value.[24] The Bank of Canada and Canadian economists often use this early form of paper currency to illustrate the true nature of money for Canadians.[23]

18th and 19th century

| Country | Year |

|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 1821 |

| Germany | 1871 |

| Sweden | 1873 |

| United States (de facto) | 1873 |

| France | 1874 |

| Belgium | 1874 |

| Italy | 1874 |

| Switzerland | 1874 |

| Netherlands | 1875 |

| Austria-Hungary | 1892 |

| Japan | 1897 |

| Russia | 1898 |

| United States (de jure) | 1900 |

An early form of fiat currency in the American Colonies was "bills of credit."[26] Provincial governments produced notes which were fiat currency, with the promise to allow holders to pay taxes with those notes. The notes were issued to pay current obligations and could be used for taxes levied at a later time.[26] Since the notes were denominated in the local unit of account, they were circulated from person to person in non-tax transactions. These types of notes were issued particularly in Pennsylvania, Virginia and Massachusetts. Such money was sold at a discount of silver, which the government would then spend, and would expire at a fixed date later.[26]

Bills of credit have generated some controversy from their inception. Those who have wanted to emphasize the dangers of inflation have emphasized the colonies where the bills of credit depreciated most dramatically: New England and the Carolinas.[26] Those who have wanted to defend the use of bills of credit in the colonies have emphasized the middle colonies, where inflation was practically nonexistent.[26]

Colonial powers consciously introduced fiat currencies backed by taxes (e.g., hut taxes or poll taxes) to mobilise economic resources in their new possessions, at least as a transitional arrangement. The purpose of such taxes was later served by property taxes. The repeated cycle of deflationary hard money, followed by inflationary paper money continued through much of the 18th and 19th centuries. Often nations would have dual currencies, with paper trading at some discount to money which represented specie.

Examples include the "Continental" bills issued by the U.S. Congress before the United States Constitution; paper versus gold ducats in Napoleonic era Vienna, where paper often traded at 100:1 against gold; the South Sea Bubble, which produced bank notes not representing sufficient reserves; and the Mississippi Company scheme of John Law.

During the American Civil War, the Federal Government issued United States Notes, a form of paper fiat currency known popularly as 'greenbacks'. Their issue was limited by Congress at slightly more than $340 million. During the 1870s, withdrawal of the notes from circulation was opposed by the United States Greenback Party. It was termed 'fiat money' in an 1878 party convention.[27]

20th century

After World War I, governments and banks generally still promised to convert notes and coins into their nominal commodity (redemption by specie, typically gold) on demand. However, the costs of the war and the required repairs and economic growth based on government borrowing afterward made governments suspend redemption by specie. Some governments were careful of avoiding sovereign default but not wary of the consequences of paying debts by consigning newly printed cash not associated with a metal standard to their creditors, which resulted in hyperinflation – for example the hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic.

From 1944 to 1971, the Bretton Woods agreement fixed the value of 35 United States dollars to one troy ounce of gold.[28] Other currencies were calibrated with the U.S. dollar at fixed rates. The U.S. promised to redeem dollars with gold transferred to other national banks. Trade imbalances were corrected by gold reserve exchanges or by loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The Bretton Woods system was ended by what became known as the Nixon shock, a series of economic changes by United States President Richard Nixon in 1971. These changes included unilaterally canceling the direct convertibility of the United States dollar to gold. Since then, a system of national fiat monies has been used globally, with variable exchange rates between the major currencies.[29]

Precious metal coinage

During the 1960s, production of silver coins for circulation ceased when the face value of the coin was less than the cost of the precious metal it contained (whereas it had been greater historically). In the United States, the Coinage Act of 1965 eliminated silver from circulating dimes and quarter dollars, and most other countries did the same with their coins.[30] The Canadian penny, which was mostly copper until 1996, was removed from circulation altogether during the autumn of 2012 due to the cost of production relative to face value.[31]

In 2007, the Royal Canadian Mint produced a million dollar gold bullion coin and sold five of them. In 2015, the gold in the coins was worth more than 3.5 times the face value.[32]

Money creation and regulation

A central bank introduces new money into an economy by purchasing financial assets or lending money to financial institutions. Commercial banks then redeploy or repurpose this base money by credit creation through fractional reserve banking, which expands the total supply of "broad money" (cash plus demand deposits).[33]

In modern economies, relatively little of the supply of broad money is physical currency. For example, in December 2010 in the U.S., of the $8,853.4 billion of broad money supply (M2), only $915.7 billion (about 10%) consisted of physical coins and paper money.[34] The manufacturing of new physical money is usually the responsibility of the national bank, or sometimes, the government's treasury.

The Bank for International Settlements published a detailed review of payment system developments in the Group of Ten (G10) countries in 1985, in the first of a series that has become known as "red books". Currently the red books cover the participating countries on Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI).[35] A red book summary of the value of banknotes and coins in circulation is shown in the table below where the local currency is converted to US dollars using the end of the year rates.[36] The value of this physical currency as a percentage of GDP ranges from a maximum of 19.4% in Japan to a minimum of 1.7% in Sweden with the overall average for all countries in the table being 8.9% (7.9% for the US).

| Country | Billions of dollars | Per capita |

|---|---|---|

| United States | $1,425 | $4,433 |

| Eurozone | $1,210 | $3,571 |

| Japan | $857 | $6,739 |

| India | $251 | $195 |

| Russia | $117 | $799 |

| United Kingdom | $103 | $1,583 |

| Switzerland | $76 | $9,213 |

| Korea | $74 | $1,460 |

| Mexico | $72 | $599 |

| Canada | $59 | $1,641 |

| Brazil | $58 | $282 |

| Australia | $55 | $2,320 |

| Saudi Arabia | $53 | $1,708 |

| Hong Kong SAR | $48 | $6,550 |

| Turkey | $36 | $458 |

| Singapore | $27 | $4,911 |

| Sweden | $9 | $872 |

| South Africa | $6 | $113 |

| Total/Average | $4,536 | $1,558 |

The most notable currency not included in this table is the Chinese yuan, for which the statistics are listed as "not available".

Inflation

The adoption of fiat currency by many countries, from the 18th century onwards, made much larger variations in the supply of money possible. Since then, huge increases in the supply of paper money have occurred in a number of countries, producing hyperinflations – episodes of extreme inflation rates much greater than those observed during earlier periods of commodity money.[37][38] The hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic of Germany is a notable example.[39][37]

Economists generally believe that high rates of inflation and hyperinflation are caused by an excessive growth of the money supply.[40] Presently, most economists favor a small and steady rate of inflation.[41] Small (as opposed to zero or negative) inflation reduces the severity of economic recessions by enabling the labor market to adjust more quickly to a recession, and reduces the risk that a liquidity trap (a reluctance to lend money due to low rates of interest) prevents monetary policy from stabilizing the economy.[42] However, money supply growth does not always cause nominal increases of price. Money supply growth may instead result in stable prices at a time in which they would otherwise be decreasing. Some economists maintain that with the conditions of a liquidity trap, large monetary injections are like "pushing on a string".[43][44]

The task of keeping the rate of inflation small and stable is usually given to monetary authorities. Generally, these monetary authorities are the national banks that control monetary policy by the setting of interest rates, by open market operations, and by the setting of banking reserve requirements.[45]

Loss of backing

A fiat-money currency greatly loses its value should the issuing government or central bank either lose the ability to, or refuse to, continue to guarantee its value. The usual consequence is hyperinflation. Some examples of this are the Zimbabwean dollar, China's money during 1945 and the Weimar Republic's mark during 1923. A more recent example is the currency instability in Venezuela that began in 2016 during the country's ongoing socioeconomic and political crisis.

This need not necessarily occur, especially if a currency continues to be the most easily available; for example, the pre-1990 Iraqi dinar continued to retain value in the Kurdistan Regional Government even after its legal tender status was ended by the Iraqi government which issued the notes.[46][47]

See also

Notes

- ↑ See Monetary economics for further discussion.

- ↑ Fīat is the third-person singular present active subjunctive of fiō ("I become", "I am made").

References

- 1 2 Goldberg, Dror (2005). "Famous Myths of "Fiat Money"". Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. 37 (5): 957–967. doi:10.1353/mcb.2005.0052. JSTOR 3839155. S2CID 54713138.

- 1 2 3

N. Gregory Mankiw (2014). Principles of Economics. Cengage Learning. p. 220. ISBN 978-1-285-16592-9.

fiat money: money without intrinsic value that is used as money because of government decree

- ↑ Walsh, Carl E. (2003). Monetary Theory and Policy. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-23231-9.

- ↑ Peter Bernholz (2003). Monetary Regimes and Inflation: History, Economic and Political Relationships. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-84376-155-6.

- ↑ Montgomery Rollins (1917). Money and Investments. George Routledge & Sons. ISBN 9781358416323. Archived from the original on December 27, 2016.

Fiat Money. Money which a government declares shall be accepted as legal tender at its face value;

- ↑ "Legal Tender Guidelines | The Royal Mint". www.royalmint.com.

- ↑ John Maynard Keynes (1965) [1930]. "1. The Classification of Money". A Treatise on Money. Vol. 1. Macmillan & Co Ltd. p. 7.

Fiat Money is Representative (or token) Money (i.e something the intrinsic value of the material substance of which is divorced from its monetary face value) – now generally made of paper except in the case of small denominations – which is created and issued by the State, but is not convertible by law into anything other than itself, and has no fixed value in terms of an objective standard.

- ↑ Blume, Lawrence E; (Firm), Palgrave Macmillan; Durlauf, Steven N (2019). The new Palgrave dictionary of economics. Palgrave Macmillan (Firm) (Living Reference Work ed.). United Kingdom. ISBN 9781349951215. OCLC 968345651.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "The Four Different Types of Money – Quickonomics". Quickonomics. September 17, 2016. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Most of the money in the economy is created by banks when they provide loans". Bank of England. October 1, 2019.

- ↑ Lagos, Ricardo & Wright, Randall (2005). "A Unified Framework for Monetary Theory and Policy Analysis". Journal of Political Economy. 113 (3): 463–84. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.563.3199. doi:10.1086/429804. S2CID 154851073..

- ↑ Harvey, David (2023). A Companion to Marx’s Grundrisse. 388 Atlantic Avenue, Brooklyn, NY, 11217: Verso. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-80429-098-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Smith, Gayle E. "Millions Will Fall Into Extreme Poverty If The U.S. And China Can't Come Together On The African Debt Crisis". Forbes. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ↑ Tabuchi, Hiroko (March 12, 2021). "Countries Tried to Curb Trade in Plastic Waste. The U.S. Is Shipping More". The New York Times.

- ↑ Kiyotaki, Nobuhiro & Wright, Randall (1989). "On Money as a Medium of Exchange". Journal of Political Economy. 97 (4): 927–54. doi:10.1086/261634. S2CID 154872512..

- ↑ Selgin, George (2003), "Adaptive Learning and the Transition to Fiat Money", The Economic Journal, 113 (484): 147–65, doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00094, S2CID 153964856.

- ↑ Von Glahn, Richard (1996), Fountain of Fortune: Money and Monetary Policy in China, 1000–1700, Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ Ramsden, Dave (2004). "A Very Short History of Chinese Paper Money". James J. Puplava Financial Sense. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008.

- ↑ David Miles; Andrew Scott (January 14, 2005). Macroeconomics: Understanding the Wealth of Nations. John Wiley & Sons. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-470-01243-7.

- ↑ Marco Polo (1818). The Travels of Marco Polo, a Venetian, in the Thirteenth Century: Being a Description, by that Early Traveller, of Remarkable Places and Things, in the Eastern Parts of the World. pp. 353–55. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ↑ Foster, Ralph T. (2010). Fiat Paper Money – The History and Evolution of Our Currency. Berkeley, California: Foster Publishing. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0-9643066-1-5.

- ↑ "How Amsterdam Got Fiat Money". www.frbatlanta.org. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- 1 2 Bank of Canada (2010). "New France (ca. 1600–1770)" (PDF). A History of the Canadian Dollar. Bank of Canada. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Playing Card Money Set". Royal Canadian Mint. 2014. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Rise and fall of the Gold Standard". news24.com. May 30, 2014. Archived from the original on May 4, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Michener, Ron (2003). "Money in the American Colonies Archived February 21, 2015, at the Wayback Machine." EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples.

- ↑ "Fiat Money". Chicago Daily Tribune. May 24, 1878.

- ↑ ""Bretton Woods" Federal Research Division Country Studies (Austria)". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010.

- ↑ Jeffrey D. Sachs, Felipe Larrain (1992). Macroeconomics for Global Economies. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0745006086.

The Bretton Woods arrangement collapsed in 1971 when U.S. President Richard Nixon suspended the convertibility of the dollar into gold. Since then, the world has lived in a system of national fiat monies, with flexible exchange rates between the major currencies

- ↑ Dave (August 22, 2014). "Silver as Money: A History of US Silver Coins". Silver Coins. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ↑ Agency, Canada Revenue (June 22, 2017). "ARCHIVED – Eliminating the penny from Canada's coinage system - Canada.ca". www.cra-arc.gc.ca. Archived from the original on May 17, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ↑ "Million Dollar Coin". www.mint.ca. Archived from the original on March 9, 2015. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ↑ Bill (September 12, 2023). "Is the Money in Your Checking Account Yours or the Bank's?". Mises Institute. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ "FRB: H.6 Release--Money Stock and Debt Measures--January 27, 2011". www.federalreserve.gov. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ↑ "About the CPMI". www.bis.org. February 2, 2016. Archived from the original on October 4, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ↑ "CPMI - BIS - Red Book: CPMI countries". www.bis.org. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- 1 2 kanopiadmin (September 21, 2004). "Weimar and Wall Street". Mises Institute. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ kanopiadmin (June 16, 2008). "Commodity Prices and Inflation: What's the Connection?". Mises Institute. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ "Hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic | Description & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ Robert Barro and Vittorio Grilli (1994), European Macroeconomics, Ch. 8, p. 139, Fig. 8.1. Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-57764-7.

- ↑ Hummel, Jeffrey Rogers. "Death and Taxes, Including Inflation: the Public versus Economists" (January 2007). "Death and Taxes, Including Inflation: The Public versus Economists · Econ Journal Watch : Inflation, deadweight loss, deficit, money, national debt, seigniorage, taxation, velocity". Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2014. p. 56

- ↑ "Escaping from a Liquidity Trap and Deflation: The Foolproof Way and Others Archived February 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine" Lars E.O. Svensson, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 17, Issue 4 Fall 2003, pp. 145–66

- ↑ John Makin (November 2010). "Bernanke Battles U.S. Deflation Threat" (PDF). AEI. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 17, 2013.

- ↑ Paul Krugman; Gauti Eggertsson. "Debt, Deleveraging, and the liquidity trap: A Fisher‐Minsky‐Koo approach" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 17, 2013.

- ↑ Taylor, Timothy (2008). Principles of Economics. Freeload Press. ISBN 978-1-930789-05-0.

- ↑ Foote, Christopher; Block, William; Crane, Keith & Gray, Simon (2004). "Economic Policy and Prospects in Iraq" (PDF). The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 18 (3): 47–70. doi:10.1257/0895330042162395..

- ↑ Budget and Finance (2003). "Iraq Currency Exchange". The Coalition Provisional Authority. Archived from the original on May 15, 2007.