Field Marshal Archibald Percival Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell, GCB, GCSI, GCIE, CMG, MC, PC (5 May 1883 – 24 May 1950) was a senior officer of the British Army. He served in the Second Boer War, the Bazar Valley Campaign and the First World War, during which he was wounded in the Second Battle of Ypres. In the Second World War, he served initially as Commander-in-Chief Middle East, in which role he led British forces to victory over the Italian Army in Eritrea-Abyssinia, western Egypt and eastern Libya during Operation Compass in December 1940, only to be defeated by Erwin Rommel's Panzer Army Africa in the Western Desert in April 1941. He served as Commander-in-Chief, India, from July 1941 until June 1943 (apart from a brief tour as Commander of American-British-Dutch-Australian Command) and then served as Viceroy of India until his retirement in February 1947.

Early life

Born the son of Archibald Graham Wavell (who later became a major-general in the British Army and military commander of Johannesburg after its capture during the Second Boer War[3] and Lillie Wavell (née Percival), Wavell attended Eaton House,[4] followed by the leading preparatory boarding school Summer Fields near Oxford, Winchester College, where he was a scholar, and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst.[5] His headmaster, Dr. Fearon, had advised his father that there was no need to send him into the Army as he had "sufficient ability to make his way in other walks of life".[3]

Early career

After graduating from Sandhurst, Wavell was commissioned into the British Army on 8 May 1901 as a second lieutenant in the Black Watch,[6] and joined the 2nd battalion of his regiment in South Africa to fight in the Second Boer War.[5] The battalion stayed in South Africa throughout the war, which formally ended in June 1902 after the Peace of Vereeniging. Wavell was ill, and did not immediately join the battalion as it transferred to British India in October that year; he instead left Cape Town for England on the SS Simla at the same time.[7] In 1903 he was transferred to join the battalion in India and, having been promoted to lieutenant on 13 August 1904,[8] he fought in the Bazar Valley Campaign of February 1908.[9] In January 1909 he was seconded from his regiment to be a student at the Staff College.[10] He was one of only two in his class to graduate with an A grade.[11] In 1911, he spent a year as a military observer with the Russian Army to learn Russian,[9] returning to his regiment in December of that year.[12] In April 1912 he became a General Staff Officer Grade 3 (GSO3) in the Russian Section of the War Office.[13] In July, he was granted the temporary rank of captain and became GSO3 at the Directorate of Military Training.[14] On 20 March 1913 Wavell was promoted to the substantive rank of captain.[15] After visiting manoeuvres at Kiev in summer 1913, he was arrested at the Russo-Polish border as a suspected spy, following a search of his Moscow hotel room by the secret police, but managed to remove from his papers an incriminating document listing the information wanted by the War Office.[16]

Wavell was working at the War Office when Army officers refused to act against Ulster unionists in March 1914; the government was expecting Unionist paramilitary opposition to introduction of devolved government in Ireland. His letters to his father record his disgust at the government's behaviour in giving an ultimatum to officers – he had little doubt that the government had been planning to crush the Ulster Scots, whatever they later claimed. However, he was also concerned at the Army's effectively intervening in politics, not least as there would be an even greater appearance of bias when the Army was used against industrial unrest.[17]

First World War

Wavell was working as a staff officer when the First World War began.[18] As a captain, he was sent to France to a posting at General HQ of the British Expeditionary Force as General Staff Officer Grade 2 (GSO2), but shortly afterwards, in November 1914, was appointed brigade major of 9th Infantry Brigade.[19] He was wounded in the Second Battle of Ypres of 1915, losing his left eye[20] and winning the Military Cross.[21] In October 1915 he became a GSO2 in the 64th Highland Division.[5]

In December 1915, after he had recovered, Wavell was returned to General HQ in France as a GSO2.[22] He was promoted to the substantive rank of major on 8 May 1916.[23] In October 1916 Wavell was graded General Staff Officer Grade 1 (GSO1) as an acting lieutenant-colonel,[24] and was then assigned as a liaison officer to the Russian Army in the Caucasus.[9] In June 1917, he was promoted to brevet lieutenant-colonel[25] and continued to work as a staff officer (GSO1),[26] as liaison officer with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force headquarters.[9]

In January 1918 Wavell received a further staff appointment as Assistant Adjutant & Quartermaster General (AA&QMG)[27] working at the Supreme War Council in Versailles.[20] In March 1918 Wavell was made a temporary brigadier general and returned to Palestine where he served as the brigadier general of the General Staff (BGGS) with XX Corps, part of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force.[20]

Between the world wars

Wavell was given a number of assignments between the wars, though like many officers he had to accept a reduction in rank. In May 1920 he relinquished the temporary appointment of Brigadier-General, reverting to lieutenant-colonel.[28] In December 1921, he became an Assistant Adjutant General (AAG) at the War Office[29] and, having been promoted to full colonel on 3 June 1921,[30] he became a GSO1 in the Directorate of Military Operations in July 1923.[31]

Apart from a short period unemployed on half pay in 1926,[32][33] Wavell continued to hold GSO1 appointments, latterly in the 3rd Infantry Division, until July 1930 when he was given command of 6th Infantry Brigade with the temporary rank of brigadier.[34] In March 1932, he was appointed aide-de-camp (ADC) to King George V,[35] a position he held until October 1933 when he was promoted to Major-General.[36][37] However, there was a shortage of jobs for Major-Generals at this time and in January 1934, on relinquishing command of his brigade, he found himself unemployed on half pay once again.[38]

By the end of the year, although still on half pay, Wavell had been designated to command 2nd Division and appointed a CB.[39] In March 1935, he took command of his division.[40] In August 1937 he was transferred to Palestine, where there was growing unrest, to be General Officer Commanding (GOC) British Forces in Palestine and Trans-Jordan[41] and was promoted to Lieutenant-General on 21 January 1938.[42]

In April 1938 Wavell became General Officer Commanding-in-Chief (GOC-in-C) Southern Command in the UK.[43] In July 1939, he was named as General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of Middle East Command with the local rank of full general.[44] Subsequently, on 15 February 1940, to reflect the broadening of his oversight responsibilities to include East Africa, Greece and the Balkans, his title was changed to Commander-in-Chief Middle East.[45]

Second World War military commands

Middle East Command (incl. North and East Africa)

The Middle Eastern theatre was quiet for the first few months of the war until Italy's declaration of war in June 1940.[46] The Italian forces in North and East Africa greatly outnumbered the British and Wavell's policy was therefore one of "flexible containment" to buy time to build up adequate forces to take the offensive. Having fallen back in front of Italian advances from their colonies Libya and Eritrea towards (respectively) Egypt and Ethiopia, Wavell mounted successful offensives into Libya (Operation Compass) in December 1940 and Eritrea and Ethiopia in January 1941. By February 1941, his Western Desert Force under Lieutenant-General Richard O'Connor had defeated the Italian Tenth Army at Beda Fomm taking 130,000 prisoners and appeared to be on the verge of overrunning the last Italian forces in Libya, which would have ended all direct Axis control in North Africa.[47] His troops in East Africa also had the Italians under pressure and at the end of March his forces in Eritrea under William Platt won the decisive battle of the campaign at Keren which led to the liberation of Ethiopia and the British occupation of the Italian colonies of Eritrea and Somaliland.[48]

In February Wavell had been ordered to halt his advance into Libya and send troops to Greece intervening in the Battle of Greece. He disagreed with this decision but followed his orders. The result was a disaster. The Germans were given the opportunity to reinforce the Italians in North Africa with the Afrika Korps and by the end of April the weakened Western Desert Force had been pushed all the way back to the Egyptian border, leading to the Siege of Tobruk.[49] In Greece General Henry Wilson's Force W was unable to set up an adequate defence on the Greek mainland and were forced to withdraw to Crete, suffering 15,000 casualties and leaving behind all their heavy equipment and artillery. In the Battle of Crete German airborne forces attacked on 20 May and as in Greece, the British and Commonwealth troops were forced once more to evacuate.[49]

Events in Greece provoked a pro-Axis faction of Iraqis to begin the 1941 Iraqi coup d'état. Wavell, hard pressed on his other fronts, was unwilling to divert precious resources to Iraq and so it fell to Claude Auchinleck's India Command to send troops to Basra. Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, saw Iraq as vital to Britain's strategic interests and in early May, under heavy pressure from London, Wavell agreed to send a division-sized force across the desert from Palestine to relieve RAF Habbaniya and to assume control of troops in Iraq. By the end of May Edward Quinan's Iraqforce had captured Baghdad and the Anglo-Iraqi War had ended with the re-establishment of the pro-British ruler and troops in Iraq once more reverting to the overall control of GHQ in Delhi. However, Churchill had been unimpressed by Wavell's reluctance to act.[49]

In early June Wavell sent a force under General Wilson to invade Syria and Lebanon, responding to the help given by the Vichy France authorities there to the Iraq Government during the Anglo-Iraqi War. Initial hopes of a quick victory faded as the French put up a determined defence. Churchill determined to relieve Wavell and after the failure in mid June of Operation Battleaxe, intended to relieve Tobruk, he told Wavell on 20 June that he was to be replaced by Auchinleck, whose attitude during the Iraq crisis had impressed him.[50] Rommel rated Wavell highly, despite Wavell's lack of success against him.[51]

Of Wavell, Auchinleck wrote: "In no sense do I wish to infer that I found an unsatisfactory situation on my arrival – far from it. Not only was I greatly impressed by the solid foundations laid by my predecessor, but I was also able the better to appreciate the vastness of the problems with which he had been confronted and the greatness of his achievements, in a command in which some 40 different languages are spoken by the British and Allied Forces."[52]

India Command

Wavell in effect swapped jobs with Auchinleck, transferring to India where he became Commander-in-Chief, India and a member of the Governor General's Executive Council.[53] Initially his command covered India and Iraq so that within a month of taking charge he launched Iraqforce to invade Persia in co-operation with the Russians in order to secure the oilfields and the lines of communication to the Soviet Union.[50]

Wavell once again had the misfortune of being placed in charge of an undermanned theatre which became a war zone when the Japanese declared war on the United Kingdom in December 1941. He was made Commander-in-Chief of ABDACOM (American-British-Dutch-Australian Command).[54]

Late at night on 10 February 1942, Wavell prepared to board a flying boat, to fly from Singapore to Java. He stepped out of a staff car, not noticing (because of his blind left eye) that it was parked at the edge of a pier. He broke two bones in his back when he fell, and this injury affected his temperament for some time.[55]

On 23 February 1942, with Malaya lost and the Allied position in Java and Sumatra precarious, ABDACOM was closed down and its headquarters in Java evacuated. Wavell returned to India to resume his position as C-in-C India where his responsibilities now included the defence of Burma.[56]

On 23 February British forces in Burma had suffered a serious setback when Major-General Jackie Smyth's decision to destroy the bridge over the Sittang river to prevent the enemy crossing had resulted in most of his division being trapped on the wrong side of the river. The Viceroy Lord Linlithgow sent a signal criticising the conduct of the field commanders to Churchill who forwarded it to Wavell together with an offer to send Harold Alexander, who had commanded the rearguard at Dunkirk. Alexander took command of Allied land forces in Burma in early March[56] with William Slim arriving shortly afterwards from commanding a division in Iraq to take command of its principal formation, Burma Corps. Nevertheless, the pressure from the Japanese Armies was unstoppable and a withdrawal to India was ordered which was completed by the end of May before the start of the monsoon season which brought Japanese progress to a halt.[57]

In order to wrest some of the initiative from the Japanese, Wavell ordered the Eastern Army in India to mount an offensive in the Arakan, which commenced in September. After some initial success the Japanese counter-attacked, and by March 1943 the position was untenable, and the remnants of the attacking force were withdrawn. Wavell relieved the Eastern Army commander, Noel Irwin, of his command and replaced him with George Giffard.[57]

In January 1943, Wavell was promoted to field marshal[58] and on 22 April he returned to London. On 4 May he had an audience with the King, before departing with Churchill for America, returning on 27 May. He resided with Henry 'Chips' Channon MP in Belgrave Square and was reintroduced by him into London society. Churchill nursed "an uncontrollable and unfortunate disapproval – indeed jealous dislike – of Wavell",[59] and had several spats with him in America.[60]

Viceroy of India

On 15 June 1943, Churchill invited Wavell to dinner and offered him the Viceroyalty of India in succession to Linlithgow. Lady Wavell joined him in London on 14 July, when they took up a suite at The Dorchester. Shortly afterwards it was announced that he had been created a viscount (taking the style Viscount Wavell of Cyrenaica and of Winchester, in the county of Southampton)[61] He addressed an all-party meeting at the House of Commons on 27 July, and on 28 July took his seat in the House of Lords as "the Empire's hero".[62] In September, he was formally named Governor-General and Viceroy of India.[63]

One of Wavell's first actions in office was to address the Bengal famine of 1943 by ordering the army to distribute relief supplies to the starving rural Bengalis. He attempted with mixed success to increase the supplies of rice to reduce the prices.[64] During his reign, Gandhi was leading the Quit India campaign, Mohammad Ali Jinnah was working for an independent state for the Muslims and Subhas Chandra Bose befriended Japan "and were pressing forward along India's Eastern border".[65]

Although Wavell was initially popular with Indian politicians, pressure mounted concerning the likely structure and timing of an independent India. He attempted to move the debate along, with the Wavell Plan and the Simla Conference, but received little support from Churchill (who was against Indian independence), nor from Clement Attlee, Churchill's successor as prime minister. He was also hampered by the differences between the various Indian political factions. At the end of the war, rising Indian expectations continued to be unfulfilled, and inter-communal violence increased. Eventually, in 1947, Attlee lost confidence in Wavell and replaced him with Lord Mountbatten of Burma.[51][66]

Later life

In 1947 Wavell returned to England and was made High Steward of Colchester. The same year, he was created Earl Wavell and given the additional title of Viscount Keren of Eritrea and Winchester.[67]

Wavell was a great lover of literature, and while Viceroy of India he compiled and annotated an anthology of great poetry, Other Men's Flowers, which was published in 1944. He wrote the last poem in the anthology himself and described it as a "...little wayside dandelion of my own".[68] He had a great memory for poetry and often quoted it at length. He is depicted in Evelyn Waugh's novel Officers and Gentlemen, part of the Sword of Honour trilogy, reciting a translation of Callimachus' poetry in public.[69] He was also a member of the Church of England and a deeply religious man.[70]

Wavell died on 24 May 1950 after a relapse following abdominal surgery on 5 May.[71] After his death, his body lay in state at the Tower of London where he had been Constable. A military funeral was held on 7 June 1950 with the funeral procession travelling along the Thames from the Tower to Westminster Pier and then to Westminster Abbey for the funeral service.[72] This was the first military funeral by river since that of Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, in 1806.[73] The funeral was attended by the then Prime Minister Clement Attlee as well as Lord Halifax and fellow officers including Field Marshals Alanbrooke and Montgomery. Winston Churchill did not attend the service.[74]

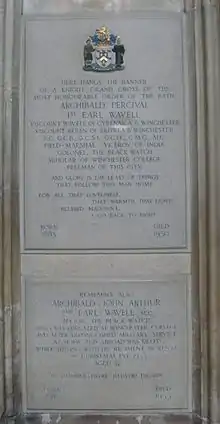

Wavell is buried in the old mediaeval cloister at Winchester College, next to the Chantry Chapel. His tombstone simply bears the inscription "Wavell". A plaque was placed in the north nave aisle of Winchester Cathedral to commemorate both Wavell and his son.[75] St Andrew's Garrison Church, Aldershot, an Army church, contains a large wooden plaque dedicated to Lord Wavell.[76]

Family

Wavell married Eugenie Marie Quirk, only daughter of Col. J. O. Quirk CB DSO, on 22 April 1915.[77] She survived him and died, as Dowager Countess Wavell, on 11 October 1987, aged 100 years.[78]

Children:

- Archibald John Arthur Wavell, later 2nd Earl Wavell, b. 11 May 1916; d. 24 December 1953, killed in Kenya, in an action against Mau Mau rebels. Since he was unmarried and without issue, the titles became extinct on his death.[79]

- Eugenie Pamela Wavell, b. 2 December 1918, married 14 March 1942 Lt.-Col. A. F. W. Humphrys MBE.

- Felicity Ann Wavell, b. 21 July 1921, married at the Cathedral Church of the Redemption, New Delhi, 20 February 1947 Capt. P. M. Longmore MC, son of Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Longmore.[80]

- Joan Patricia Quirk Wavell, b. 23 April 1923, married

- (1) 27 January 1943 Maj. Hon. Simon Nevill Astley (b. 13 August 1919; d. 16 March 1946), 2nd son of Albert Edward Delaval [Astley], 21st Baron Hastings, by his wife Lady Margueritte Helen Nevill, only child by his second wife of Henry Gilbert Ralph [Nevill], 3rd Marquess of Abergavenny.

- (2) 19 June 1948 Maj. Harry Alexander Gordon MC (d. 19 June 1965), 2nd son of Cdr. Alastair Gordon DSO RN.

- (3) Maj. Donald Struan Robertson (d. 1991), son of the Rt. Hon. Sir Malcolm Arnold Robertson GCMG KBE.

Honours and awards

Ribbon bar (as it would look today)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

British

- Military Cross – 3 June 1915[81]

- Mention in Despatches 22 June 1915, 4 January 1917, 22 January 1919[20]

- Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) – 1 January 1919[39]

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB) – 4 March 1941[82] (KCB: 2 January 1939;[83] CB: 1 January 1935[84])

- Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India (GCSI) – 18 September 1943[85]

- Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire (GCIE) – 18 September 1943[85]

- Knight of the Order of St. John – 4 January 1944[86]

Others

- Order of St Stanislaus, 3rd class with Swords (Russia) (12 September 1916)[87]

- Order of St. Vladimir (Russia) 1917[20]

- Croix de Guerre (Commandeur) (France) – 4 May 1920[88]

- Commandeur, Légion d'honneur (France) – 7 May 1920[89]

- Order of El Nahda, 2nd Class (Hejaz) – 30 September 1920[90]

- Grand Cross, Order of George I with Swords (Greece) – 9 May 1941[91]

- Virtuti Militari, 5th Class (Poland) – 23 September 1941[92]

- War Cross, 1st Class (Greece) – 10 April 1942[93]

- Commander, Order of the Seal of Solomon (Ethiopia) – 5 May 1942[94]

- Grand Cross, Order of Orange-Nassau (Netherlands) – 15 January 1943[95]

- War Cross (Czechoslovakia) – 23 July 1943[96]

- Legion of Merit degree of Chief Commander (United States) – 23 July 1948[97]

Quotes

- "I think he (Benito Mussolini) must do something, if he cannot make a graceful dive he will at least have to jump in somehow; he can hardly put on his dressing-gown and walk down the stairs again."[98]

- "After the 'war to end war', they seem to have been pretty successful in Paris at making the 'Peace to end Peace.'"[99] (commenting on the treaties ending the First World War; this quotation was the basis for the title of David Fromkin's A Peace to End All Peace, New York: Henry Holt, (1989) ISBN 0-8050-6884-8)

- "Let us be clear about three facts: First, all battles and all wars are won in the end by the infantryman. Secondly, the infantryman always bears the brunt. His casualties are heavier, he suffers greater extremes of discomfort and fatigue than the other arms. Thirdly, the art of the infantryman is less stereotyped and far harder to acquire in modern war than that of any other arm."[100]

Publications

Books

- Tsar Nicholas II by Andrei Georgievich Elchaninov. Translated from the Russian by Archibald Percival Wavell. Hugh Rees. 1913.

- The Tsar and his People by Andrei Georgievich Elchaninov. Translated from the Russian by Archibald P. Wavell. Hugh Rees. 1914.

- The Palestine Campaigns. London: Constable. 1933. OCLC 221723716.

- Allenby, A Study in Greatness: The Biography of Field-Marshal Viscount Allenby of Megiddo and Felixstowe, G.C.B., G.C.M.G. London: Harrap. 1940–43. OCLC 224016319.

- Generals and Generalship: The Lees Knowles Lectures Delivered at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1939. London. 1941. OCLC 5176549.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Soldiers and Soldiering or Epithets of War. London: J. Cape. 1953. OCLC 123277730.

- Other Men's Flowers: An Anthology of Poetry. London: J. Cape. 1977 [1944]. OCLC 10681637.

- Other Men's Flowers: An Anthology of Poetry (Memorial ed.). London: Pimlico. 1992 [1952].; "this first paperback edition contains not only Lord Wavell's own introduction and annotations, but also the introduction written by his son, to whom the book was originally dedicated".

- Allenby, Soldier and Statesman. London: White Lion. 1974 [1946]. ISBN 0-85617-408-4.

- Speaking Generally: broadcasts, Orders and Addresses in time of war (1939–43). London: Macmillan. 1946. OCLC 2172221.

- The Good Soldier. London: Macmillan. 1948. OCLC 6834669.

- Wavell: The Viceroy's Journal. London: Oxford University Press. 1973. ISBN 0-19-211723-8.

Official despatches

- "Operations In The Western Desert from December 7th, 1940 to February 7th, 1942", sent to Secretary of State for War June 1941 and published in "No. 37628". The London Gazette (Supplement). 25 June 1946. pp. 3261–3269.

- "Operations in The Middle East from 7th February 1941 to 15th July 1941", submitted 5 September 1941 published in "No. 37638". The London Gazette (Supplement). 2 July 1946. pp. 3423–3444.

- "Operations In Iraq, East Syria and Iran from 10th April 1941 to 12th January 1942" published in "No. 37685". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 August 1946. pp. 4093–4101.

- "Operations in Eastern Theatre, Based on India, From March 1942 to December 31, 1942" published in "No. 37728". The London Gazette (Supplement). 17 September 1946. pp. 4663–4671.

See also

Citations

- ↑ "No. 38712". The London Gazette. 13 September 1949. p. 4397.

- ↑ "No. 38241". The London Gazette. 19 March 1948. p. 1933.

- 1 2 Schofield 2006, p. 15.

- ↑ "Mr T. S. Morton". The Times. 23 January 1962.

- 1 2 3 Heathcote 1999, p. 287.

- ↑ "No. 27311". The London Gazette. 7 May 1901. p. 3130.

- ↑ "The Army in South Africa - Troops returning Home". The Times. No. 36899. London. 15 October 1902. p. 8.

- ↑ "No. 27710". The London Gazette. 2 September 1904. p. 5697.

- 1 2 3 4 "Archibald Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell". Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives. Archived from the original on 25 December 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "No. 28221". The London Gazette. 5 February 1909. p. 946.

- ↑ Schofield 2006, p. 33.

- ↑ "No. 28578". The London Gazette. 6 February 1912. p. 881.

- ↑ "No. 28597". The London Gazette. 9 April 1912. p. 2585.

- ↑ "No. 28626". The London Gazette. 12 July 1912. p. 5083.

- ↑ "No. 28720". The London Gazette. 20 May 1913. p. 3592.

- ↑ Schofield 2006, p. 39.

- ↑ Schofield 2006, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Adrian Fort, Archibald Wavell: The Life and Death of the Imperial Servant (2009) ch 3.

- ↑ "No. 28994". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 December 1914. p. 10278.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Archibald Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell". Unit histories. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "No. 29202". The London Gazette (Supplement). 22 June 1915. p. 6118.

- ↑ "No. 29389". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 November 1915. p. 12037.

- ↑ "No. 29605". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 May 1916. p. 5439.

- ↑ "No. 30002". The London Gazette. 27 March 1917. p. 3001.

- ↑ "No. 30111". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 June 1917. p. 5465.

- ↑ "No. 30178". The London Gazette (Supplement). 10 July 1917. p. 6953.

- ↑ "No. 30528". The London Gazette (Supplement). 15 February 1918. p. 2130.

- ↑ "No. 31893". The London Gazette (Supplement). 7 May 1920. p. 5345.

- ↑ "No. 32568". The London Gazette (Supplement). 5 January 1922. p. 143.

- ↑ "No. 32728". The London Gazette. 11 July 1922. p. 5204.

- ↑ "No. 32844". The London Gazette. 13 July 1923. p. 4854.

- ↑ "No. 33123". The London Gazette. 12 January 1926. p. 299.

- ↑ "No. 33219". The London Gazette. 9 November 1926. p. 7255.

- ↑ "No. 33623". The London Gazette. 8 July 1930. p. 4271.

- ↑ "No. 33807". The London Gazette. 11 March 1931. p. 1679.

- ↑ "No. 33992". The London Gazette. 3 November 1933. p. 7107.

- ↑ "No. 33987". The London Gazette. 17 October 1933. p. 6692.

- ↑ "No. 34015". The London Gazette. 16 January 1934. p. 390.

- 1 2 "No. 31093". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 1918. p. 52.

- ↑ "No. 34143". The London Gazette. 19 March 1935. p. 1905.

- ↑ "No. 34430". The London Gazette. 27 August 1937. p. 5439.

- ↑ "No. 34482". The London Gazette. 15 February 1938. p. 968.

- ↑ "No. 34506". The London Gazette. 28 April 1938. p. 2781.

- ↑ "No. 34650". The London Gazette. 1 August 1939. p. 5311.

- ↑ Playfair, Vol. I, page 63.

- ↑ Raugh (2013), pp. 96–131.

- ↑ Mead 2007, p. 473.

- ↑ Mead 2007, pp. 473–475.

- 1 2 3 Mead 2007, p. 475.

- 1 2 Mead 2007, p. 476.

- 1 2 Mead 2007, p. 480.

- ↑ Auchinleck, p. 4215

- ↑ "No. 35222". The London Gazette. 18 July 1941. p. 4152.

- ↑ Klemen, L (1999–2000). "General Sir Archibald Percival Wavell". Dutch East Indies Campaign website. Archived from the original on 3 April 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ Allen 1984, pp. 644–645.

- 1 2 Mead 2007, p. 478.

- 1 2 Mead 2007, p. 479.

- ↑ "No. 35841". The London Gazette. 29 December 1942. p. 33.

- ↑ Channon 1987, p. 355.

- ↑ Channon 1987, pp. 358, 362.

- ↑ "No. 36105". The London Gazette. 23 July 1943. p. 3340.

- ↑ Channon 1987, p. 373.

- ↑ "No. 36208". The London Gazette. 12 October 1943. p. 4513.

- ↑ Heathcote 1999, p. 290.

- ↑ "Wavell". Lively Stories. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ↑ Glynn, p. 639-663

- ↑ "No. 37956". The London Gazette. 16 May 1947. p. 2190.

- ↑ Mead 2007, p. 481.

- ↑ Frame 2008, p. 90.

- ↑ "Our War Leaders in Peacetime – Wavell in The War Illustrated, Volume 10, No. 237". 19 July 1946. p. 213. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "Lord Wavell, British War Leader, Dies". Oxnard Press-Courier. 24 May 1950. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "A Great Soldier Passes". British Pathé. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "Lord Wavell Given Hero's Funeral in Heat Wave Like Africa Desert". The Montreal Gazette. 8 June 1950. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ Schofield 2006, pp. 394–395.

- ↑ "Field Marshal Earl Wavell and Major Earl Wavell MC". Imperial War Museum. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ↑ "History of St. Andrew's Garrison Church". St Andrew's Garrison Church, Aldershot. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ H.J.J. Sargint (11 July 1943). "Lady Wavell". The Palm Beach Post. p. 20.

- ↑ "Dowager Countess Wavell". Online dictionary of distinguished women, Index W. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "Earl Wavell Dies in 10-Hour Fight With Terrorists". The Calgary Herald. 26 December 1953. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ↑ "Wavell's daughter weds". Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ↑ "No. 29202". The London Gazette (Supplement). 22 June 1915. p. 6118.

- ↑ "No. 35094". The London Gazette. 4 March 1941. p. 1303.

- ↑ "No. 34585". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 December 1938. p. 3.

- ↑ "No. 34119". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 December 1934. p. 4.

- 1 2 "No. 36208". The London Gazette. 12 October 1943. p. 4513.

- ↑ "No. 36315". The London Gazette. 4 January 1944. p. 114.

- ↑ "No. 29945". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 August 1917. p. 1601.

- ↑ "No. 31890". The London Gazette (Supplement). 4 May 1920. p. 5228.

- ↑ "No. 31890". The London Gazette (Supplement). 7 May 1920. p. 5228.

- ↑ "No. 32069". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 September 1920. p. 9606.

- ↑ "No. 35157". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 May 1941. p. 2648.

- ↑ "No. 35282". The London Gazette (Supplement). 23 September 1941. p. 5501.

- ↑ "No. 35519". The London Gazette (Supplement). 7 April 1942. p. 1595.

- ↑ "No. 35546". The London Gazette (Supplement). 5 May 1942. p. 1961.

- ↑ "No. 35863". The London Gazette (Supplement). 12 January 1943. p. 323.

- ↑ "No. 36103". The London Gazette (Supplement). 20 July 1943. p. 3319.

- ↑ "No. 38359". The London Gazette (Supplement). 23 July 1948. p. 4189.

- ↑ Quoted in Axelrod, p. 180

- ↑ Pagden, p. 407

- ↑ In Praise of Infantry, Field-Marshal Earl Wavell, "The Times", Thursday, 19 April 1945

General sources

- Allen, Louis (1984). Burma: The Longest War. J. M. Dent and Sons. ISBN 0-460-02474-4.

- Auchinleck, Claude (1946). Despatch on Operations in the Middle East from 5 July 1941 to 31 October 1941. London: War Office. "No. 37695". The London Gazette (Supplement). 20 August 1946. pp. 4215–4230.

- Axelrod, Alan (2008). The Real History of World War II. Sterling Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4027-4090-9.

- Channon, Henry (1987). Rhodes James, R. (ed.). Chips: The Diaries of Sir Henry Channon. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Close, H. M. (1997). Attlee, Wavell, Mountbatten, and the Transfer of Power. National Book Foundation.

- Connell, John (1 January 1964). Wavell: Scholar and Soldier. Collins.

- Connell, John (1 April 1969). Wavell, Supreme Commander. Collins. ISBN 978-0002119207.

- Fort, Adrian. Archibald Wavell: The Life and Death of the Imperial Servant (2009)

- Frame, Alex (2008). Flying Boats: My Father's War in the Mediterranean. Victoria University Press. ISBN 978-0864735621.

- Heathcote, Tony (1999). The British Field Marshals 1736–1997. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 0-85052-696-5.

- Glynn, Irial (2007). "An Untouchable in the Presence of Brahmins: Lord Wavell's Disastrous Relationship with Whitehall During His Time as Viceroy to India, 1943–7". Modern Asian Studies. 41 (3): 639–663. doi:10.1017/S0026749X06002460. S2CID 143934881.

- Houterman, Hans; Koppes, Jeroen. "World War II Unit Histories and Officers". Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- Mead, Richard (2007). Churchill's Lions: A Biographical guide to the Key British Generals of World War II. Stroud: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-431-0.

- Pagden, Anthony (2008). Worlds at War: The 2,500-year Struggle between East and West. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-923743-2.

- Playfair, Major-General I. S. O.; with Flynn, Captain F. C. (RN); Molony, Brigadier C. J. C. & Gleave, Group Captain T. P. (2009) [1st. pub. HMSO: 1954]. Butler, Sir James (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Early Successes Against Italy, to May 1941. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. I. Uckfield, UK: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-065-8.

- Raugh, Harold E. Jr. (2013). Wavell in the Middle East, 1939–1941: A Study in Generalship. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806143057.

- Schofield, Victoria (2006). Wavell: Soldier and Statesman. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-71956-320-1.

- Wavell, Archibald Percival Wavell (1973). Wavell: The Viceroy's Journal. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192117236.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)