| First Dáil | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Overview | |||||

| Legislative body | Dáil Éireann | ||||

| Jurisdiction | Irish Republic | ||||

| Meeting place | Mansion House, Dublin[1] | ||||

| Term | 21 January 1919 – 16 August 1921[2] | ||||

| Election | 1918 general election | ||||

| Government | Government of the 1st Dáil | ||||

| Members | 73 | ||||

| Ceann Comhairle | Cathal Brugha (1919) George Noble Plunkett (1919) Seán T. O'Kelly (1919–21) | ||||

| President of Dáil Éireann | Cathal Brugha (1919) | ||||

| President of the Irish Republic | Éamon de Valera (1919–21) | ||||

| Sessions | |||||

| |||||

The First Dáil (Irish: An Chéad Dáil) was Dáil Éireann as it convened from 1919 to 1921. It was the first meeting of the unicameral parliament of the revolutionary Irish Republic. In the December 1918 election to the Parliament of the United Kingdom, the Irish republican party Sinn Féin won a landslide victory in Ireland. In line with their manifesto, its MPs refused to take their seats, and on 21 January 1919 they founded a separate parliament in Dublin called Dáil Éireann ("Assembly of Ireland").[3] They declared Irish independence, ratifying the Proclamation of the Irish Republic that had been issued in the 1916 Easter Rising, and adopted a provisional constitution.

Its first meeting happened on the same day as one of the first engagements of what became the Irish War of Independence. Although the Dáil had not authorised any armed action, it became a "symbol of popular resistance and a source of legitimacy for fighting men in the guerrilla war that developed".[4]

The Dáil was outlawed by the British government in September 1919, and thereafter it met in secret. The First Dáil met 21 times and its main business was establishing the Irish Republic.[3] It created the beginnings of an independent Irish government and state apparatus. Following the May 1921 elections, the First Dáil was succeeded by the Second Dáil of 1921–1922.

Background

In the early 20th century Ireland was a part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and was represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom by 105 Members of Parliament (MPs). From 1882, most Irish MPs were members of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) who strove in several Home Rule Bills to achieve self-government for Ireland within the United Kingdom. This resulted in the Government of Ireland Act 1914, but its implementation was postponed with the outbreak of the First World War.[5]

The founder of the small Sinn Féin party, Arthur Griffith, believed Irish nationalists should emulate the Hungarian nationalists who had gained legislative independence from Austria. In 1867, Hungarian representatives had boycotted the Imperial parliament in Vienna and unilaterally established their own legislature in Budapest, resulting in the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. Griffith argued that Irish nationalists should follow this "policy of passive resistance – with occasional excursions into the domain of active resistance".[6]

In April 1916, during the First World War, Irish republicans launched an uprising against British rule in Ireland, the Easter Rising. They proclaimed an Irish Republic. After a week of heavy fighting, mostly in Dublin, the rising was put down by British forces. About 3,500 people were taken prisoner by the British, many of whom had played no part in the Rising. Most of the Rising's leaders were executed. The rising, the British response, and the British attempt to introduce conscription in Ireland, led to greater public support for Sinn Féin and Irish independence.[7]

In the 1918 general election, Sinn Féin won 73 out of the 105 Irish seats in the House of Commons. In 25 constituencies, Sinn Féin won the seats unopposed. Elections were held almost entirely under the 'first-past-the-post voting' system.[8] The recent Representation of the People Act had increased the Irish electorate from around 700,000 to about two million.[9] Unionists (including the Ulster Unionist Labour Association) won 26 seats, all but three of which were in east Ulster, and the IPP won only six (down from 84), all but one in Ulster. The Labour Party did not stand in the election, allowing the electorate to decide between home rule or a republic by having a clear choice between the two nationalist parties. The IPP won a smaller share of seats than votes due to the first-past-the-post system.[10]

Sinn Féin's manifesto had pledged to establish an Irish Republic by founding "a constituent assembly comprising persons chosen by Irish constituencies" which could then "speak and act in the name of the Irish people". Once elected the Sinn Féin MPs chose to follow through with their manifesto.[11]

First meeting

Sinn Féin had held several meetings in early January to plan the first sitting of the Dáil. On 8 January, it publicly announced its intention to convene the assembly. On the night of 11 January, the Dublin Metropolitan Police raided Sinn Féin headquarters and seized drafts of the documents that would be issued at the assembly. As a result, the British administration was fully aware what was being planned.[12]

The first meeting of Dáil Éireann began at 3:30 pm on 21 January in the Round Room of the Mansion House, the residence of the Lord Mayor of Dublin.[13] It lasted about two hours. The packed audience in the Round Room rose in acclaim for the members of the Dáil as they walked into the room, and many waved Irish tricolour flags.[14] A tricolour was also displayed above the lectern.[15] Among the audience were the Lord Mayor Laurence O'Neill and Maud Gonne.[15] Scores of Irish and international journalists were reporting on the proceedings. Outside, Dawson Street was thronged with onlookers. Irish Volunteers controlled the crowds, and police were also present.[15] Precautions had been taken in case the assembly was raided by the British authorities.[16] A reception for British soldiers of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, who had been prisoners of war in Germany, had ended shortly beforehand.[15]

Twenty-seven Sinn Féin MPs attended. Invitations had been sent to all elected MPs in Ireland, but the Unionists and Irish Parliamentary Party MPs declined to attend. The IPP's Thomas Harbison, MP for North East Tyrone, acknowledged the invitation but wrote he should "decline for obvious reasons". He expressed sympathy with the call for Ireland to have a hearing at the Paris Peace Conference.[17] Sir Robert Henry Woods was the only unionist who declined rather than ignored his invitation.[18] Sixty-nine Sinn Féin MPs had been elected (four of whom represented more than one constituency), but thirty-four were in prison, and eight others could not attend for various reasons.[19] Those in prison were described as being "imprisoned by the foreigners" (fé ghlas ag Gallaibh).[20] Michael Collins and Harry Boland were marked in the roll as i láthair (present), but the record was later amended to show that they were as láthair (absent). At the time, they were in England planning the escape of Éamon de Valera from Lincoln Prison, and did not wish to draw attention to their absence.[11]

Being a first and highly symbolic meeting, the proceedings of the Dáil were held wholly in the Irish language, although translations of the documents were also read out in English and French.[15] George Noble Plunkett opened the session and nominated Cathal Brugha as acting Ceann Comhairle (chairman or speaker), which was accepted. Both actions "immediately associated the Dáil with the 1916 Rising, during which Brugha had been seriously wounded, and after which Plunkett’s son had been executed as a signatory to the famed Proclamation".[11] Brugha then called upon Father Michael O'Flanagan to say a prayer.[11][15]

Declarations and constitution

A number of short documents were then read out and adopted. These were the:

- Dáil Constitution

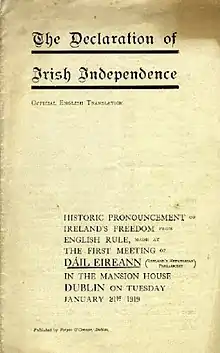

- Declaration of Independence

- Message to the Free Nations of the World – calling for international recognition of Irish independence

- Democratic Programme – a declaration of social and economic policy[19]

These documents asserted that the Dáil was the parliament of a sovereign state called the "Irish Republic". With the Declaration of Independence, the Dáil ratified the Proclamation of the Irish Republic that had been issued in the 1916 Rising,[19] and pledged "to make this declaration effective by every means". It stated that "the elected representatives of the Irish people alone have power to make laws binding on the people of Ireland, and that the Irish Parliament is the only Parliament to which that people will give its allegiance". It also declared "foreign government in Ireland to be an invasion of our national right" and demanded British military withdrawal.[21] Once the Declaration was read, Cathal Brugha said (in Irish): "Deputies, you understand from what is asserted in this Declaration that we are now done with England. Let the world know it and those who are concerned bear it in mind. For come what may now, whether it be death itself, the great deed is done".[22]

The Message to the Free Nations called for international recognition of Irish independence and for Ireland to be allowed to make its case at the Paris Peace Conference.[19] It stated that "the existing state of war between Ireland and England can never be ended until Ireland is definitely evacuated by the armed forces of England". Although this could have been a "rhetorical flourish", it was the nearest the Dáil came to a declaration of war.[23]

The Dáil Constitution was a brief provisional constitution. It stated that the Dáil had "full powers to legislate" and would be composed of representatives "chosen by the people of Ireland from the present constituencies of the country". It established an executive government or Ministry (Aireacht) made up of a president (Príomh-Aire) chosen by the Dáil, and ministers of finance, home affairs, foreign affairs and defence. Cathal Brugha was elected as the first, temporary president.[19] He would be succeeded, in April, by Éamon de Valera.

Reactions

The first meeting of the Dáil and its declaration of independence was headline news in Ireland and abroad.[24] However, the press censorship that began during the First World War was continued by the British administration in Ireland after the war. The Press Censor forbade all Irish newspapers from publishing the Dáil's declarations.[25]

That evening, a British unionist view of events was printed in a newspaper. It said that the British Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, "Lord French, is today the master of Ireland. He alone [...] will decide upon the type of government the country is to have, and it is he rather than any member of the House of Commons, who will be the judge of political and industrial reforms".[16] Lord French's observer at the meeting, George Moore, was impressed by its orderliness and told French that the Dáil represented "the general feeling in the country".[15] The Irish Times, then the voice of the Unionist status quo, called the events both farcical and dangerous.[24]

Irish republicans, and many nationalist newspapers, saw the meeting as momentous and the beginning of "a new epoch".[24] According to one observer: "It is difficult to convey the intensity of feeling which pervaded the Round Room, the feeling that great things were happening, even greater things impending, and that in looking around the room he saw a glimpse of the Ireland of the future".[15]

One American journalist was more accurate than most when he forecast that "The British government apparently intends to ignore the Sinn Fein republic until it undertakes to enforce laws that are in conflict with those established by the British; then the trouble is likely to begin".[24]

Irish War of Independence

1st row (left to right): L. Ginnell, M. Collins, C. Brugha, A. Griffith, É. de Valera, G. Plunkett, E. MacNeill, W. T. Cosgrave and E. Blythe.

2nd row (l to r): P. J. Moloney, T. MacSwiney, R. Mulcahy, J. O'Doherty, S. O'Mahony, J. Dolan, J. McGuinness, P. O'Keefe, M. Staines, J. McGrath, B. Cusack, L. de Róiste, M. Colivet and M. O'Flanagan[lower-alpha 1]

3rd row (l to r): P. Ward, A. McCabe, D. FitzGerald, J. Sweeny, R. Hayes, C. Collins, P. Ó Máille, J. O'Mara, B. O'Higgins, S. Burke and K. O'Higgins.

4th row (l to r): J. McDonagh and S. MacEntee.

5th row (l to r): P. Béaslaí, R. Barton and P. Galligan.

6th row (l to r): P. Shanahan and S. Etchingham.

Members of the Irish Volunteers, a republican paramilitary organization, "believed that the election of the Dáil and its declaration of independence had given them the right to pursue the republic in the manner they saw fit".[26] It began to refer to itself as the Irish Republican Army (IRA).[27] The First Dáil was "a visible symbol of popular resistance and a source of legitimacy for fighting men in the guerrilla war that developed".[4]

On the same day as the Dáil's first meeting, two officers of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) were killed in an ambush in County Tipperary by members of the Irish Volunteers. The Volunteers seized the explosives the officers had been guarding. This action had not been authorised by the Irish Volunteer leadership nor by the Dáil. Although the Dáil and the Irish Volunteers had some overlapping membership, they were separate and neither controlled the other.[26]

After the founding of the Dáil, steps were taken to make the Volunteers the army of the new self-declared republic. On 31 January 1919 the Volunteers' official journal, An tÓglách ("The Volunteer"), stated that Ireland and England were at war, and that the founding of Dáil Éireann and its declaration of independence justified the Irish Volunteers in treating "the armed forces of the enemy – whether soldiers or policemen – exactly as a national army would treat the members of an invading army".[27] In August 1920, the Dáil adopted a motion that the Irish Volunteers, "as a standing army", would swear allegiance to it and to the Republic.[28]

The Soloheadbeg ambush "and others like it that occurred during 1919 were not […] intended to be the first shots in a general war of independence, though that is what they turned out to be".[29] It is thus seen as one of the first actions of the Irish War of Independence. The Dáil did not debate whether it would "accept a state of war" with, or declare war on, the United Kingdom until 11 March 1921.[30] It was agreed unanimously to give President de Valera the power to accept or declare war at the most opportune time, but he never did so.

In September 1919 the Dáil was declared illegal by the British authorities and thereafter met only intermittently and at various locations.[31] The Dáil also set about attempting to secure de facto authority for the Irish Republic throughout the country. This included the establishment of a parallel judicial system known as the Dáil Courts. The First Dáil held its last meeting on 10 May 1921. After elections on 24 May the Dáil was succeeded by the Second Dáil which sat for the first time on 16 August 1921.[32]

Legacy

The First Dáil and the general election of 1918 came to occupy a central place in Irish republicanism and nationalism. Today the name Dáil Éireann is used for the lower house of the modern Oireachtas (parliament) of the Republic of Ireland. Successive Dála (plural for Dáil) continue to be numbered from the "First Dáil" convened in 1919. The current Dáil, elected in 2020, is accordingly the "33rd Dáil". The 1918 general election was the last time the whole island of Ireland voted as a unit[33] until elections to the European Parliament over sixty years later. The landslide victory for Sinn Féin was seen by Irish republicans as an overwhelming endorsement of the principle of a united independent Ireland.[33] Until recently republican paramilitary groups, such as the Provisional IRA, often claimed that their campaigns derived legitimacy from this 1918 mandate, and some still do.

The First Dáil "created the beginnings of an independent Irish governmental and bureaucratic machine", and was a means by which "a formal constitution for the new state was created".[4] It also "provided the personnel and the authority to conclude the articles of agreement with Britain and bring the war to an end".[4] The Irish state has commemorated the founding of the First Dáil several times, as "the anniversary of when a constitutionally elected majority of MPs declared the right of the Irish people to have their own democratic state".[34]

Seán MacEntee, who died on 10 January 1984 at the age of 94, was the last surviving member of the First Dáil.[35]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ “First Dáil meets in Mansion House". .

- ↑ de Valera, Éamon (16 August 1921). "Prelude –". Dáil Éireann (2nd Dáil) debates. Oireachtas. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

Members of the Dáil, in accordance with the decision arrived at last Session, it is my privilege and my duty to open the new Dáil. Until the moment the Speaker left the Chair, the old Dáil was in session. The new Dáil is in session now.

- 1 2 "Explainer: Establishing the First Dáil". Century Ireland.

- 1 2 3 4 Farrell, Brian. The Founding of Dáil Éireann: Parliament and Nation Building. Gill and Macmillan, 1971. p.81

- ↑ Hennessey, Thomas (1998). Dividing Ireland: World War I and Partition. Routledge. p. 76. ISBN 0-415-17420-1.

- ↑ Laffan, Michael (1999). The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Féin Party, 1916–1923. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3, 18.

- ↑ Coleman, Marie (2013). The Irish Revolution, 1916–1923. Routledge. pp. 33, 39. ISBN 978-1317801474.

- ↑ The exception to the use of this system were the constituencies of Dublin University and Cork City. The two Unionist representatives returned for the Dublin University (Trinity College) were elected under the single transferable vote, and the two Sinn Féin candidates elected for Cork City were returned under the bloc voting system.

- ↑ Jackson, Alvin (2010). Ireland 1798–1998: War, Peace and Beyond. John Wiley & Sons. p. 210.

- ↑ Sovereignty and partition, 1912–1949 pp. 59–62, M. E. Collins, Edco Publishing (2004), ISBN 1-84536-040-0

- 1 2 3 4 "The inaugural public meeting of Dáil Éireann". Oireachtas.

- ↑ Mitchell, Arthur. Revolutionary Government in Ireland. Gill & MacMillan, 1995. p.12

- ↑ Ellis, Peter Berresford. Eyewitness to Irish History. Wiley, 2004. pp.230–231

- ↑ "Dáil Éireann meets in Mansion House". Century Ireland.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mitchell, Revolutionary Government in Ireland, p.17

- 1 2 Comerford, Maire. The First Dáil. J Clarke, 1969. pp.51–54

- ↑ "Roll Call, Wednesday 22 January 2019". Oireachtas.

- ↑ Hayes, Cathy; Byrne, Patricia M. "Woods, Sir Robert Henry". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lyons, Francis. "The war of independence", in A New History of Ireland: Ireland Under the Union. Oxford University Press, 2010. pp.240–241

- ↑ "Roll call of the first sitting of the First Dáil". Dáil Éireann Parliamentary Debates (in Irish). Archived from the original on 19 November 2007.

- ↑ Lynch, Robert. Revolutionary Ireland, 1912–25. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015. pp.140–142

- ↑ Townshend, Charles. Political Violence in Ireland: Government and Resistance Since 1848. Clarendon Press, 1983. p.328

- ↑ Smith, Michael. Fighting for Ireland?: The Military Strategy of the Irish Republican Movement. Routledge, 2002. p.32

- 1 2 3 4 "Press coverage of the First Dáil". Oireachtas.

- ↑ Carty, James. Bibliography of Irish History 1912–1921. Irish Stationery Office, 1936. p.xxiii

- 1 2 Smith, Fighting for Ireland?, pp.56–57

- 1 2 Townshend, Political Violence in Ireland, p.332

- ↑ Lawlor, Sheila. Britain and Ireland, 1914–23. Gill and Macmillan, 1983. p.38

- ↑ Lyons, p.244

- ↑ "Dáil Éireann – Volume 1–11 March 1921 – PRESIDENT'S STATEMENT". Oireachtas. 11 March 1921. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ↑ Mitchell, Revolutionary Government in Ireland, p.245

- ↑ Curran, Joseph. The Birth of the Irish Free State. University of Alabama Press, 1980. p.68

- 1 2 Tonge, Jonathan. Northern Ireland: Conflict and Change. Routledge, 2013. p.12

- ↑ "Controlling History: Commemorating the First Dáil, 1929–1969". The Irish Story. 19 February 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ↑ "Mr. Seán MacEntee". Oireachtas Members Database. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

Notes

- ↑ VP of Sinn Féin, not a TD.

External links

- Oireachtas website:

- Debates by year Archived 31 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Members since 1919

- Records of Dáil Éireann 1919–1922 from Digital Repository of Ireland