| Flamingo Las Vegas | |

|---|---|

| |

Flamingo Las Vegas in 2005 | |

| |

| Location | Paradise, Nevada, U.S. |

| Address | 3555 South Las Vegas Boulevard |

| Opening date | December 26, 1946 |

| Theme | Art Deco Miami |

| No. of rooms | 3,460 |

| Total gaming space | 72,299 sq ft (6,716.8 m2) |

| Permanent shows | Piff the Magic Dragon RuPaul's Drag Race Live! Wayne Newton X Burlesque |

| Signature attractions | Wildlife habitat |

| Notable restaurants | Bugsy & Meyer's Steakhouse Club Cappuccino Jimmy Buffett's Margaritaville Nook Express |

| Casino type | Land-based |

| Owner | Caesars Entertainment |

| Previous names | Flamingo Hilton Las Vegas (1974–2000) |

| Renovated in | 1953, 1967, 1974, 1977, 1982, 1990, 1993, 2004, 2009, 2014, 2018 |

| Coordinates | 36°6′58″N 115°10′14″W / 36.11611°N 115.17056°W |

| Website | caesars |

Flamingo Las Vegas (formerly Flamingo Hilton Las Vegas) is a casino hotel on the Las Vegas Strip in Paradise, Nevada. It is owned and operated by Caesars Entertainment.

The property includes a 72,299-square-foot (6,716.8 m2) casino along with 3,460 hotel rooms. The architectural theme is reminiscent of the Art Deco and Streamline Moderne style of Miami and South Beach. Staying true to its theme and name, the hotel includes a garden courtyard which serves as a wildlife habitat for flamingos. The hotel was the third resort to open on the Strip and remains the oldest resort on the Strip in operation today, and it has been since 2007 with the closure and demolition of The New Frontier. It is also the last remaining casino on the strip that opened before 1950 that is still in operation. The Flamingo has a Las Vegas Monorail station called the Flamingo & Caesars Palace station at the rear of the property. After opening in 1946, it has undergone a number of ownership changes.

History

Land background and hotel design (1945)

The Flamingo site occupies 40 acres (16 ha) originally owned by one of Las Vegas's first settlers, Charles "Pops" Squires. Squires paid $8.75 per acre ($21.6/ha) for the land. In 1944, Margaret Folsom bought the tract for $7,500 from Squires, and she then later sold it to Billy Wilkerson. Wilkerson was the owner of The Hollywood Reporter as well as some very popular nightclubs on the Sunset Strip: Cafe Trocadero, Ciro's and La Rue's (Hollywood).[1]

In 1945, Wilkerson purchased 33 acres (13 ha) on the east side of U.S. Route 91, or about a half mile south of the Hotel Last Frontier, in preparation for his vision. Wilkerson then hired George Vernon Russell to design a hotel influenced by European style. The El Rancho Vegas and The Last Frontier were full service hotel casinos, and already open on what would become known as The Las Vegas Strip. Wilkerson also requested that the new 'Flamingo' hotel be different from the smaller "sawdust joints" on Fremont Street. He planned a hotel with luxurious rooms, a spa, a health club, a showroom, a golf course, a nightclub, an upscale restaurant and a French-style casino. Because of high wartime material costs, Wilkerson ran into financial problems almost at once, finding himself $400,000 short and hunting for new financing.

Development under Bugsy Siegel (1946)

Wilkerson received a $1 million check in February 1946 from G. Harry Rothberg in exchange for a two-thirds interest in the hotel project from for his partners. They included Moe Sedway, Gus Greenbaum, and another individual Wilkerson would meet in March 1946: Benjamin Siegel.[2]

Sometime in Spring 1946 the hotel name became 'Flamingo' but is no verifiable information to say when, or by whom the name was given. An apocryphal tale says Siegel named the resort after his girlfriend, Virginia Hill. According to Billy Wilkerson's son and biographer, 'Flamingo' received its name from Wilkerson, but there is no evidence to support the claim, and no evidence of the project baring the name 'Flamingo' before Siegel's association.[3][4][2]

In summer of 1946, Siegel announced a decision that made him the on-site boss. With off-the-books financier Meyer Lansky's blessing, he created the Nevada Projects Corporation, formalized on June 20, 1946, for the explicit purpose of building a hotel-casino according to Siegel's vision, not Wilkerson's.[2]

The Flamingo Hotel & Casino opens (1946)

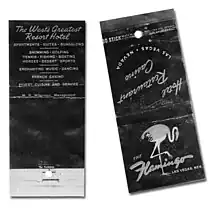

Siegel finally opened The Flamingo Hotel & Casino on December 26, 1946, at a total cost of $6 million.[5] Billed as "The West's Greatest Resort Hotel", the 105-room property—and first luxury hotel on the Strip[6]—was built 4 miles (6.4 km) from Downtown Las Vegas. During construction, a large sign announced the hotel as a William R. Wilkerson project. The sign also read Del Webb Construction as the hotel's primary contractor and Richard R. Stadelman (who later made renovations to the El Rancho Vegas) as the building architect.

Post-Siegel ownerships (1947–1960)

Siegel was killed on June 20, 1947, and after his death, Moe Sedway and Gus Greenbaum, magnates of the nearby El Cortez Hotel, took possession of the hotel. Under their partnership, it became a non-exclusive facility affordable to almost anyone. They made the enterprise extremely successful. In the year 1948 alone, it turned a $4 million profit.[7] The Fabulous Flamingo presented lavish shows and accommodations for its time, becoming well known for comfortable, air-conditioned rooms, gardens, and swimming pools. Often credited for popularizing the "complete experience" as opposed to merely gambling, its staff became known for wearing tuxedos on the job.

In 1953, the hotel's management spent $1 million in renovations and remodeling. The original entrance and signage was destroyed. A new entrance with an upswept roof was built and a pink neon sign was designed by Bill Clark of Ad-Art. A neon-bubbled "Champagne Tower" sign with pink flamingos rimming the top was also installed in front of the hotel.[8] From 1955 to 1960, the property was operated by Albert Parvin of the Parvin-Dohrmann Corporation.[9] Parvin owned 30% of the stock while businessman Harry Goldman owned 7.5%; other investors included singer Tony Martin and actor George Raft.[10]

Recent years (1960–present)

In 1960, it was sold for $10.5 million to a group including Morris Lansburgh and Daniel Lifter, Miami residents with reputed ties to organized crime.[9][11] Lansky allegedly served as middleman for the deal, receiving $200,000.[9][10]

Kirk Kerkorian acquired the property in 1967,[12] making it part of Kerkorian's International Leisure Company, but the Hilton Corporation bought the resort in 1972, renaming it the Flamingo Hilton in 1974. The last of the original Flamingo Hotel structure was torn down on December 14, 1993, and the hotel's garden was built on-site. The Flamingo's four hotel towers were built (or expanded) in 1977, 1980, 1983, 1986, 1990, and 1993. A 200-unit Hilton Grand Vacations timeshare tower was opened in 1993.[13]

In 1998, Hilton's gambling properties, including the Flamingo, were spun off as Park Place Entertainment (later renamed to Caesars Entertainment). The deal included a two-year license to use the Hilton name. Park Place opted not to renew that agreement when it expired in late 2000, and the property was renamed Flamingo Las Vegas.[14]

In 2005, Harrah's Entertainment purchased Caesars Entertainment, Inc. and the property became part of Harrah's Entertainment. The company changed its name to Caesars Entertainment Corporation in 2010.

On September 9, 2012, Port Adelaide Football Club AFL footballer John McCarthy died after falling 30 feet (9 m) from a rooftop of the hotel. The incident occurred at the start of a post-season holiday for McCarthy and other Port Adelaide players. They had arrived in Las Vegas only a few hours before the incident.[15][16][17] After reviewing evidence, police said that McCarthy had attempted to jump off the roof onto a palm tree but fell to the ground.[18]

The hotel underwent a $90-million makeover which was completed in 2018.[19] The designer, Forrest Perkins, used gold and pink in the 3500 upgraded rooms and described them as contemporary retro-chic with a focus on the 70-year history of the hotel.

Facilities and attractions

The 15-acre (6.1 ha) site's architectural theme is reminiscent of the Art Deco and Streamline Moderne style of Miami and South Beach, with a garden courtyard housing a wildlife habitat featuring flamingos. It was the third resort to open on the Strip, and it is the oldest resort on the Strip still in operation today. The Flamingo has a Las Vegas Monorail station, the Flamingo/Caesars Palace station, at the rear of the property.

The garden courtyard houses a wildlife habitat featuring Chilean flamingos, ringed teal ducks and other birds. There are also koi fish and turtles.[20] It was once the home of penguins, but they have since been moved to the Dallas Zoo.[21] Extending the hotel's tropical theme, a Jimmy Buffett's Margaritaville restaurant and gift shop was opened in December 2003.[22] An adjacent Margaritaville "minicasino" opened in October 2011.[23]

Live entertainment

Jimmy Durante and Rose Marie performed on opening night, and the latter became a frequent entertainer there in the years to follow.[24][25] Other notable early performers included Tony Martin,[26] Lena Horne, Louis Armstrong,[27] and Della Reese.[28] Wayne Newton became a headliner at the Flamingo in 1963,[29] and had a residency there during 2006.[30] He began another residency in 2022.[31][32][33] Comedian George Wallace also entertained at the Flamingo during the 2000s.[30]

In 1963, Bobby Darin recorded his live album The Curtain Falls: Live at the Flamingo, which went un-released until 2000.[34] Bill Cosby recorded his third comedy album, titled Why Is There Air?, at the resort in 1965.[35] Singer Tom Jones also recorded a live album there, titled Tom Jones Live in Las Vegas and released in 1969.[36][37]

Main venue

.jpg.webp)

The primary entertainment venue is the 700-seat Flamingo Showroom.[38] City Lites, an ice-skating show, opened there in 1981.[39][40] The initial budget was approximately $1 million. The show proved to be popular,[41] running until 1995.[42] It was replaced by The Great Radio City Spectacular, a dance show starring the Rockettes and Susan Anton, which ran for five years.[42][43][44] Bottoms Up, a long-running local show featuring topless dancers, debuted at the Flamingo Showroom in 2000, and ran for four years.[45]

A show by songwriter Rita Abrams, based on the book Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus, had a 10-month run in the showroom, ending in 2001.[46] Gladys Knight & the Pips played the venue from 2002 to 2005,[47] and singer Toni Braxton had a show there from 2006 to 2008, eventually closing due to health problems.[48][49][50]

Brother-sister musical duo Donny and Marie Osmond opened in the showroom in September 2008,[51][52] helping the Flamingo stay profitable amid the Great Recession.[53] The show was originally intended for a six-week run, but was continually extended due to its popularity.[54][52] After five years, the venue was renamed the Donny & Marie Showroom.[55][56] They ended their residency in November 2019,[56][57] after 1,730 performances.[58]

Following the Osmonds' departure, the venue name was changed back to the Flamingo Showroom. RuPaul's Drag Race Live! debuted there in January 2020, featuring drag queens who once competed on RuPaul's Drag Race and RuPaul's Drag Race All Stars, including Aquaria, Derrick Barry, and Yvie Oddly.[59][60] The show surpassed 500 performances in 2023.[61]

Other residencies in the showroom have included singer Olivia Newton-John, whose show Summer Nights ran from April 2014 through December 2016.[62][63][64] Paula Abdul had a residency from 2019 to 2020, with her Forever Your Girl production.[65]

Secondary venue

A 230-seat venue, Bugsy's Celebrity Theatre, was added as part of an expansion in 1992. It is named after Siegel,[66][67][68] and was later renamed Bugsy's Cabaret.[69] A musical, Forever Plaid, ended its six-year run at the theater in 2001, after more than 3,500 performances.[70][71] It was replaced by The Second City, an improvisational comedy group with a rotating cast of performers. The Second City debuted in 2001,[72][73] and ran for several years.[74][75]

X Burlesque, featuring female dancers, opened at the theater in 2007.[76][77] Piff the Magic Dragon, a comedic entertainer, has performed at the Flamingo since 2015,[78] initially using the same stage as X Burlesque. The venue was renamed after Piff in 2019,[79][80] until he moved to the main showroom a year later.[38][81] Piff's sidekicks include showgirl and spouse Jade Simone, and a chihuahua named Mr. Piffles.[82][81]

In popular culture

Film

The Flamingo made numerous film appearances in its early years, including The Invisible Wall (1947),[83][84] The Lady Gambles (1949),[83] My Friend Irma Goes West (1950),[85] The Las Vegas Story (1952),[83][86] and The Girl Rush (1955).[83]

In Ocean's 11 (1960), the Flamingo is one of five Las Vegas casinos to be robbed by the main characters.[87] The resort also appears in a flashback sequence in the the 2001 remake.[88] Viva Las Vegas (1964) includes prominent footage of the Flamingo's pool area.[89] The resort later appeared in Elvira: Mistress of the Dark (1988).[90]

The 1991 film Bugsy, starring Warren Beatty, depicted Siegel's involvement in the construction of the Flamingo, though many of the details were altered for dramatic effect. For instance, in the film, Siegel originates the idea of the Flamingo, instead of buying ownership from Wilkerson, and is killed after the first opening in 1946, rather than the second opening in 1947.[91] The film helped popularize the myth of Siegel as the Flamingo's true visionary.[92][93] The original Flamingo was recreated for the film through sets, based on research such as historic photographs.[94]

Television

The Flamingo Hilton is featured prominently in the opening montage of the television series Vega$ (1978–1981).[95] The series Lilyhammer (2012–2014) also features a nightclub in Lillehammer, Norway, named the Flamingo. During its construction, character Frank Tagliano references Siegel and the hotel-casino as his inspiration for the nightclub.[96]

Literature

Hunter S. Thompson and Oscar Zeta Acosta stayed at the Flamingo while attending a seminar by the National Conference of District Attorneys on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs held at the Dunes Hotel across the street. Several of their experiences in their room are depicted in Thompson's 1971 novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.[97]

The Flamingo figures prominently in the 1992 novel Last Call by Tim Powers. In the novel, the Flamingo is supposedly founded on Siegel's mythical/mystical paranoia of being pursued and killed for his archetypal position as the "King of the West", known mythologically as "Fisher King". Supposedly the Flamingo itself was meant to be a real-life personification of "The Tower" card of the tarot deck.[98][99]

See also

References

- ↑ Lewis, Jon (2017). Hard-Boiled Hollywood: Crime and Punishment in Postwar Los Angeles. University of California Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780520284326.

- 1 2 3 Shnayerson, Michael. Bugsy Siegel: The Dark Side of the American Dream. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22619-5.

- ↑ "More Las Vegas FAQs". Travel Channel. August 26, 2007. Retrieved October 6, 2007.

- ↑ "The Fabulous Flamingo Hotel History: The Wilkerson-Siegel Years". classiclasvegas.squarespace.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ↑ Koch, Ed; Manning, Mary; Toplikar, Dave (May 15, 2008). "Showtime: How Sin City evolved into 'The Entertainment Capital of the World'". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ↑ Levitan, Corey (September 26, 2008). "Gritty City". The Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ↑ Wilkerson III, W. R. (2000). The Man Who Invented Las Vegas. Ciro's Books. pp. 111, 115.

- ↑ "The Fabulous Flamingo Hotel History in the 1950s". Archived from the original on April 12, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Mobster key man in hotel sale". St. Petersburg Independent. October 22, 1969. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- 1 2 Heller, Jean (October 30, 1969). "Funds For Parvin Foundation Came From Flamingo Hotel Sale". The Evening Sun. Hanover, Pennsylvania. p. 29. Retrieved August 29, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

Harry Goldman, Parvin's partner in Parvin-Dohrmann—a multimillion-a-year hotel supply business in Los Angeles—held 77⁄1 percent. Other stockholders included singer Tony Martin and actor George Raft.

- ↑ Balboni, Alan (2006). Beyond the Mafia: Italian Americans and the development of Las Vegas. University of Nevada Press. p. 62. ISBN 9780874176810.

- ↑ "Nevada Gaming Abstract - MGM MIRAGE Company Profile". Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ Heller, Jean (February 6, 2004). "Hilton adds third Las Vegas time share". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ↑ "Three Nevada casinos dropping 'Hilton' name". Las Vegas Sun. August 15, 2000. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ↑ "Statement: John McCarthy". Port Adelaide Football Club. September 10, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ↑ "AFL footballer John McCarthy dies in Las Vegas". The Sydney Morning Herald. September 10, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ↑ Walsh, Courtney (September 11, 2012). "No suspicious circumstances in John McCarthy's Las Vegas death, says coroner". The Australian. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ↑ Drill, Stephen; Langmaid, Adrian (September 12, 2012). "AFL footballer John McCarthy aimed for palm tree in roof jump as 'deeply shocked' Port Adelaide players arrive home after teammate's tragic death in Las Vegas". Herald Sun. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ↑ "Caesars Launches $90M Makeover at Flamingo Las Vegas". www.cpexecutive.com. May 23, 2017. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ↑ "Las Vegas: The Epic Guide to Drinking, Gambling and Entertainment". Backstreet Nomad. February 5, 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ↑ Wood, Crystal; Koepp, Leah (September 14, 2011). Explorer's Guide Las Vegas: A Great Destination. Countryman Press. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-1-58157-910-9. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ↑ "Margaritaville opens at Flamingo". Las Vegas Sun. December 15, 2003. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ↑ "Margaritaville Casino to hire 250 workers". Las Vegas Sun. August 16, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ↑ "Hotel took root in desert". Golden Rain News. September 1, 1988. Retrieved January 12, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Knightly, Marcy (November 3, 2017). "Rose Marie, who performed at the Flamingo opening in 1946, remembers it well". The Mob Museum. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Thomas, Bob (July 31, 2012). "Singer Tony Martin, 'the ultimate crooner,' dies". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Associated Press. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Swanston, Brenna (March 15, 2018). "History of the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas". USA Today. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ "Della is Irked at Hamp, Darin". The Bridgeport Post. August 24, 1962. Retrieved January 13, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Katsilometes, John (August 30, 2023). "'I would have to get a real job': Wayne Newton extends Flamingo residency". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- 1 2 Weatherford, Mike (February 3, 2006). "Newton, Wallace have little in common aside from the same showroom". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on September 1, 2006.

- ↑ Radke, Brock (January 28, 2022). "Wayne Newton is back to guide audiences through his legendary career in Las Vegas". Las Vegas Magazine. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Katsilometes, John (May 16, 2023). "'Mr. Las Vegas' Wayne Newton extends Flamingo production". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ della Cava, Marco (August 29, 2023). "You can see Wayne Newton perform in Las Vegas into 2024, but never at a karaoke bar". USA Today. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ "Bobby Darin - The Curtain Falls: Live at the Flamingo". AllMusic. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ↑ "Why Is There Air?". AllMusic. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ↑ McKay, Janis L. (2016). Played Out on the Strip: The Rise and Fall of Las Vegas Casino Bands. University of Nevada Press. ISBN 978-1-943859-03-0. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ↑ Zoglin, Richard (2020). Elvis in Vegas: How the King Reinvented the Las Vegas Show. Simon and Schuster. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-5011-5120-0. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- 1 2 Radke, Brock (December 6, 2021). "Piff the Magic Dragon rolls into three more years at Flamingo Las Vegas". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ "Showmen who created 'Razzle Dazzle' team up to produce 'City-Lites' at the Flamingo Hilton". Los Angeles Times. November 8, 1981. Retrieved January 13, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "'City Lites' Sparkles On Stage At The Flamingo Hilton". The Arizona Republic. May 30, 1982. Retrieved January 13, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Veteran Strip show producer Arnold dies". Las Vegas Sun. December 30, 1997. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- 1 2 "Rockettes hoof their way to Las Vegas for indefinite run". Arizona Daily Star. January 29, 1995. Retrieved January 13, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Delaney, Joe (February 11, 2000). "Tireless Taylor gives life to 'Radio City' at Flamingo". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ "Rockettes perform final show". Las Vegas Sun. July 31, 2000. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Retrieved January 14, 2024:

- Maddox, Kate (July 2, 2000). "Flamingo to bare 'Bottoms Up'". Las Vegas Sun.

- Delaney, Joe (August 18, 2000). "'Bottoms Up' is in top form at Flamingo Las Vegas". Las Vegas Sun.

- Maddox, Kate (February 24, 2001). "'Bottoms Up' lifting Flamingo". Las Vegas Sun.

- "'Bottoms Up' to say goodbye to Flamingo". Las Vegas Sun. September 29, 2004.

- ↑ Weatherford, Mike (July 31, 2001). "Flamingo in no hurry to fill vacant showroom, official says". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on December 25, 2001.

- ↑ Retrieved January 13, 2024:

- Patterson, Spencer (November 28, 2003). "Knight in Vegas". Las Vegas Sun.

- Delaney, Joe (February 15, 2002). "Knight gives it her all in Flamingo show". Las Vegas Sun.

- Fink, Jerry (February 21, 2003). "At Flamingo, the sun never sets on Knight". Las Vegas Sun.

- Weatherford, Mike (March 14, 2011). "Gladys Knight settling in at Trop". Las Vegas Review-Journal.

- ↑ "Braxton not in sync". Las Vegas Sun. August 29, 2006. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ "Toni Braxton Show canceled". Los Angeles Times. May 29, 2008. Archived from the original on June 2, 2008.

- ↑ Weatherford, Mike (August 28, 2008). "'Dancing' deja vu for Flamingo". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ "Donny & Marie set at Flamingo through 2013 -- and likely longer". lasvegasweekly.com. January 8, 2013. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- 1 2 "Donny and Marie Osmond's Las Vegas show will end after 11 years". USA Today. Associated Press. March 21, 2019. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Katsilometes, John (February 13, 2009). "In tough times, Flamingo's feathers unruffled". Las Vegas Weekly. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ↑ Jones, Jay (October 24, 2018). "Donny and Marie Osmond to call it quits on Las Vegas show". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Means, Sean P. (October 7, 2013). "Donny & Marie get their Vegas showroom named after them". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- 1 2 Forgione, Mary (November 11, 2019). "Donny and Marie close their 11-year run in Las Vegas". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Przybys, John (November 12, 2019). "Donny and Marie: A look back at their Las Vegas residency". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Trepany, Charles (November 18, 2019). "'Goodnight, everybody': Marie and Donny Osmond close Las Vegas live show after 11 years". USA Today. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Katsilometes, John (September 7, 2019). "'Ru Paul's Drag Race Live!' opening at Flamingo Las Vegas". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Radke, Brock (January 23, 2020). "'RuPaul's Drag Race Live' brings its fabulousness to the Flamingo". Las Vegas Weekly. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Kelemen, Matt (June 30, 2023). "'RuPaul's Drag Race Live!' celebrates 500 shows this summer in Vegas". Las Vegas Magazine. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Jones, Jay (February 13, 2014). "Las Vegas: Olivia Newton-John to perform at the Flamingo". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Stapleton, Susan (January 15, 2015). "'Grease' stars Olivia Newton-John and Didi Conn reunite in Las Vegas". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Katsilometes, John (August 8, 2022). "Flamingo series highlighted Newton-John's Las Vegas history". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ "Caesars announces Paula Abdul residency at Flamingo". KVVU. May 1, 2019. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020.

- ↑ "Impersonator show to open at Bugsy's Celebrity Theatre". Los Angeles Times. October 25, 1992. Retrieved January 13, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Recognition comes late". Reno Gazette-Journal. October 29, 1992. Retrieved January 13, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Flamingo Hilton remembers Bugsy Siegel during 50th anniversary". Las Vegas Review-Journal. May 16, 1997. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Fink, Jerry (August 18, 2008). "Comic takes raunchy act to bigger digs at the Flamingo". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ "Top 5 Shows: In Vegas". The Honolulu Advertiser. June 18, 1995. Retrieved January 12, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "'Forever Plaid' left to ponder life after Flamingo". Las Vegas Sun. December 15, 2000. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ Maddox, Kate (January 9, 2001). "Flamingo lining up for Seconds". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ Delaney, Joe (March 16, 2001). "'Second City' settles in nicely at Flamingo Las Vegas' showroom". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ "Second to none: 'The Second City' chugs along at Flamingo Las Vegas". Las Vegas Sun. August 29, 2002. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ "Split-second timing crucial for 'City' comedy troupe at Flamingo". Las Vegas Sun. January 14, 2005. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ Weatherford, Mike (March 2, 2007). "X Burlesque". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Katsilometes, John (April 20, 2022). "Steeped in Vegas history, 'X Burlesque' hits No. 20 at Flamingo". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Stapleton, Susan (June 18, 2015). "'X Comedy Uncensored Fun' brings a magic dragon, impersonator and more". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ "1 theater, 2 shows, 3 titles on the Las Vegas Strip". Las Vegas Review-Journal. May 24, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ↑ Palmer, Rob (July 23, 2019). "The Dragons of CSICon". Skeptical Inquirer. Center for Inquiry. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- 1 2 Katsilometes, John (October 27, 2021). "Piff still breathing fire with three-year Flamingo extension". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Katsilometes, John (January 22, 2021). "Piff ready to fire it up once more at Flamingo". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- 1 2 3 4 Gragg, Larry (2013). Bright Light City: Las Vegas in Popular Culture. University Press of Kansas. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-7006-1903-0. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ Stoldal, Bob (August 27, 2015). "Vegas goes dark". Nevada Public Radio. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ Epting, Chris (December 30, 2003). "Reel Las Vegas". NBC News. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ↑ Hawley, Tom (July 6, 2016). "Video Vault | 'Las Vegas Story' sought to be U.S. version of 'Casablanca'". KSNV. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ Abramovitch, Seth (May 31, 2018). "Hollywood Flashback: How Sinatra and the Men of 'Ocean's 11' Made Vegas 'Pop' in 1960". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ↑ "Scene In Nevada: Ocean's Eleven". Nevada Film Office. June 8, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ↑ Taylor, F. Andrew (May 15, 2014). "Many 'Viva Las Vegas' filming sites remain unchanged". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ↑ "Video Vault: Horror Hostess 'Elvira' started career as Vegas' youngest showgirl". KSNV. September 24, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ Gragg, Larry (December 22, 2021). "Separating fact from fiction on the Flamingo Hotel's 75th anniversary". The Mob Museum. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ↑ Whitely, Joan (February 10, 2000). "New book credits Hollywood Reporter publisher with dreaming up modern Las Vegas". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on August 20, 2001.

- ↑ Fink, Jerry (February 15, 2000). "Book examines 'The Man Who Invented Las Vegas'". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ↑ Benenson, Laurie Halpern (September 1, 1991). "'Bugsy' Taps a Mobster's Lavish Dream". The New York Times. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ Vega$ TV intro (1978).

- ↑ "Blogging Season 1 of Lilyhammer by Netflix". Critics Rant. December 31, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ↑ Vredenburg, Jason (February 2013). "What Happens in Vegas: Hunter S. Thompson's Political Philosophy". Journal of American Studies. 47 (1): 154. doi:10.1017/S0021875812001314. JSTOR 23352511. S2CID 143197858.

- ↑ "Last Call". Kirkus Reviews. April 20, 1992. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ↑ Baude, Dawn-Michelle (October 24, 2015). "Look beyond The Strip: Las Vegas has reinvented itself as a literary destination". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 14, 2024.