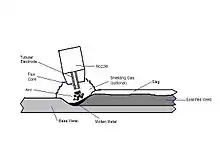

Flux-cored arc welding (FCAW or FCA) is a semi-automatic or automatic arc welding process. FCAW requires a continuously-fed consumable tubular electrode containing a flux and a constant-voltage or, less commonly, a constant-current welding power supply. An externally supplied shielding gas is sometimes used, but often the flux itself is relied upon to generate the necessary protection from the atmosphere, producing both gaseous protection and liquid slag protecting the weld.

Types

One type of FCAW requires no shielding gas. This is made possible by the flux core in the tubular consumable electrode. However, this core contains more than just flux. It also contains various ingredients that when exposed to the high temperatures of welding generate a shielding gas for protecting the arc. This type of FCAW is attractive because it is portable and generally has good penetration into the base metal. Also, windy conditions need not be considered. Some disadvantages are that this process can produce excessive, noxious smoke (making it difficult to see the weld pool). As with all welding processes, the proper electrode must be chosen to obtain the required mechanical properties. Operator skill is a major factor as improper electrode manipulation or machine setup can cause porosity.

Another type of FCAW uses a shielding gas that must be supplied by an external source. This is known informally as "dual shield" welding. This type of FCAW was developed primarily for welding structural steels. In fact, since it uses both a flux-cored electrode and an external shielding gas, one might say that it is a combination of gas metal (GMAW) and FCAW. The most often used shielding gases are either straight carbon dioxide or argon carbon dioxide blends. The most common blend used is 75% Argon 25% Carbon Dioxide.[1] This particular style of FCAW is preferable for welding thicker and out-of-position metals. The slag created by the flux is also easy to remove. The main advantages of this process is that in a closed shop environment, it generally produces welds of better and more consistent mechanical properties, with fewer weld defects than either the SMAW or GMAW processes. In practice it also allows a higher production rate, since the operator does not need to stop periodically to fetch a new electrode, as is the case in SMAW. However, like GMAW, it cannot be used in a windy environment as the loss of the shielding gas from air flow will produce porosity in the weld.

Process variables

- Wire feed speed

- Arc voltage

- Electrode extension

- Travel speed

- Electrode angles

- Electrode wire type

- Shielding gas composition (if required)

- Reverse polarity (Electrode Positive) is used for FCAW Gas-Shielded wire, Straight polarity (Electrode Negative) is used for self shielded FCAW

- Contact tip to work distance (CTWD)

Advantages and applications

- FCAW may be an "all-position" process with the right filler metals (the consumable electrode)

- No shielding gas needed with some wires making it suitable for outdoor welding and/or windy conditions

- A high-deposition rate process (speed at which the filler metal is applied) in the 1G/1F/2F

- Some "high-speed" (e.g., automotive) applications

- As compared to SMAW and GTAW, there is less skill required for operators.

- Less precleaning of metal required

- Metallurgical benefits from the flux such as the weld metal being protected initially from external factors until the slag is chipped away

- Porosity chances very low

- Less equipment required, easier to move around (no gas bottle)

Used on the following alloys:

- Mild and low alloy steels

- Stainless steels

- Some high nickel alloys

- Some wearfacing/surfacing alloys

Disadvantages

Of course, all of the usual issues that occur in welding can occur in FCAW such as incomplete fusion between base metals, slag inclusion (non-metallic inclusions), and cracks in the welds. But there are a few concerns that come up with FCAW that are worth taking special note of:

- Melted contact tip – when the contact tip actually contacts the base metal, fusing the two and melting the hole on the end.

- Irregular wire feed – typically a mechanical problem.

- Porosity – the gases (specifically those from the flux-core) don’t escape the welded area before the metal hardens, leaving holes in the welded metal.

- More costly filler material/wire as compared to GMAW.

- The amount of smoke generated can far exceed that of SMAW, GMAW, or GTAW.[2]

- Changing filler metals requires changing an entire spool. This can be slow and difficult as compared to changing filler metal for SMAW or GTAW.

References

- ↑ ""CHOOSING A SHIELDING GAS FOR FLUX-CORED WELDING"". Archived from the original on 2019-03-02. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- ↑ American Society of Safety Engineers, Are Welding Fumes an Occupational Health Risk Factor? Archived 2013-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- American Welding Society, Welding Handbook, Vol 2 (9th ed.)

- "Flux Cored Welding." Welding Procedures & Techniques. 23 June 2006. American Metallurgical Consultants. 13 Sep 2006 <http://www.weldingengineer.com/1flux.htm>.

- Groover, Mikell P. Fundamentals of Modern Manufacturing. Second. New York City: John Wiley & Sons, INC, 2002.

- "Solid Wire Versus Flux-Cored Wire - When to Use Them and Why." Miller Electric Mfg. Co. 13 Sep 2006 <http://www.millerwelds.com/education/articles/article62.html Archived 2006-10-15 at the Wayback Machine>.

- History Of Flux Cored Arc Welding before 1950's