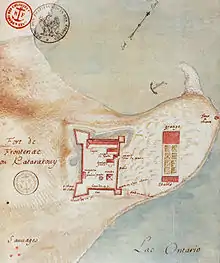

| Fort Frontenac (formerly Fort Cataraqui) | |

|---|---|

| Part of chain of French forts throughout Great Lakes and upper Mississippi region. | |

| Mouth of Cataraqui River, Kingston, Ontario, Canada | |

Remnants of the old fort with the new Fort Frontenac in background | |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Original: New France |

| Condition | Present fort: military barrack buildings used as college. Remnants of original stone fort can be seen. |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1673 |

| Built by | Louis de Buade de Frontenac |

| In use | 1673– present. Periods of abandonment. |

| Materials | Original: wood palisade, partially rebuilt with stone in 1675, rebuilt completely of stone 1695. |

| Demolished | 1689 but later rebuilt. Destroyed by British, 1758. Partly rebuilt, 1783. |

| Battles/wars | Iroquois siege, 1688, Battle of Fort Frontenac (Seven Years' War), 1758 |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | French, British, Canadian |

| Designated | 1923 |

Fort Frontenac was a French trading post and military fort built in July 1673 at the mouth of the Cataraqui River where the St. Lawrence River leaves Lake Ontario (at what is now the western end of the La Salle Causeway), in a location traditionally known as Cataraqui. It is the present-day location of Kingston, Ontario, Canada. The original fort, a crude, wooden palisade structure, was called Fort Cataraqui but was later named for Louis de Buade de Frontenac, Governor of New France who was responsible for building the fort. It was abandoned and razed in 1689, then rebuilt in 1695.

The British destroyed the fort in 1758 during the Seven Years' War and its ruins remained abandoned until the British took possession and reconstructed it in 1783. In 1870–71 the fort was turned over to the Canadian military, who continue to use it.

History

Establishment and early use

The intent of Fort Frontenac was to control the lucrative fur trade in the Great Lakes Basin to the west and the Canadian Shield to the north. It was one of many French outposts that would be established throughout the Great Lakes and upper Mississippi regions. The fort was meant to be a bulwark against the English who were competing with the French for control of the fur trade. By constructing the trading post the French could encourage trade with the Iroquois, who were traditionally a threat to the French because of their alliance with the English. Another function of the fort was the provision of supplies and reinforcements to other French installations on the Great Lakes and in the Ohio Valley to the south.

Explorer René Robert Cavalier de La Salle was ordered by governor Daniel de Rémy de Courcelle to select a location for a fort. He selected the strategic junction of Lake Ontario, the Cataraqui River, and the St. Lawrence River. Governor Louis de Buade de Frontenac, de Courcelle's successor, was concerned about further Iroquois threats, and endorsed La Salle's proposal. Governor Frontenac and his close associates also hoped to personally benefit from building the fort by controlling trade.[1][2] Frontenac, along with his entourage, journeyed up the St. Lawrence to the fort's future site where he met leaders of the Five Nations of the Iroquois on July 12, 1673 to encourage them to trade with the French, and to begin the fort's construction. The fort, which was constructed of wood surrounded by a wooden stockade consisting of sharpened poles, was completed within six days.[3][4] La Salle administered the fort and built storage buildings and dwellings, brought in domestic animals and ensured some land outside the fort was cultivated with the aim of attracting settlers.[5]

The fort was sited to protect a small sheltered bay (the "cannotage")[6] that the French could use as a harbour for large lake-going boats. Unlike the Ottawa River fur trade route into the interior, which was only accessible by canoes, larger vessels could easily navigate the lower lakes. The cost of transporting goods such as furs, trade items, and supplies through at least the lower Great Lakes would be reduced.[7]

La Salle was granted seigneurial privileges in the vicinity of the fort. In return for these privileges, La Salle was obliged to reimburse Frontenac for expenses related to building the fort, keep 20 workers onsite for two years, and maintain the fort. In 1675, La Salle rebuilt the structure. Stone bastions and a stone wall were constructed to strengthen the fort and much of the wooden pallisade was rebuilt. He was also required to attract settlers and meet their spiritual needs by building a chapel and establishing a mission with one or two Recollet priests.[8] A description of the fort written in the 17th century mentions that:

Three quarters of it are of masonry or hardstone, the wall is three feet thick and twelve high. There is one place where it is only four feet, not being completed. The remainder is closed in with stakes. There is inside a house of squared logs, a hundred feet long. There is also a blacksmith's shop a guardhouse, a house for the officers, a well, and a cow-house. The ditches are fifteen feet wide. There is a good amount of land cleared and sown around about, in which a hundred paces away or almost there is a barn for storing the harvest. There are quite near the fort several French houses, an Iroquois village, a convent and a Recollet church.[9]

La Salle used Fort Frontenac as a convenient base for his explorations into the interior of North America.

Iroquois siege and reconstruction

Fur trade rivalries continued to cause friction between the French and the Iroquois in the 1680s. The French began a campaign against the Iroquois to resolve the Iroquois threat, beginning with Governor Antoine Lefèbvre de La Barre's unsuccessful expedition to Fort Frontenac and into Seneca territory south of Lake Ontario in 1684. In 1687 La Barre's successor, the Marquis de Denonville, gathered an army to travel into the Seneca territory. To quell suspicion about his motives, Denonville let on that he was merely travelling to a peace council at Fort Frontenac. As Denonville and his army moved up the St. Lawrence toward the fort, several Iroquois, many of whom were friendly to the French, including women and children and some prominent leaders, were captured and imprisoned at Fort Frontenac by intendant de Champigny ostensibly to prevent them from revealing Denonville's troops' location.[10][11] Some were held hostage and sent to Montreal in the event that any French were captured, and some were sent to France to be used as galley slaves. Denonville's troops and native allies went on to attack the Seneca.

In retaliation for these incidents the Iroquois laid siege to Fort Frontenac and blockaded Lake Ontario. The fort and the settlement at Cataraqui were besieged for two months in 1688. Although the fort was not destroyed, the settlement was devastated and many inhabitants died, mostly from scurvy. The French abandoned and destroyed the fort in 1689, claiming that its remoteness prevented proper defense and that it could not be adequately supplied. The French again took possession of the fort in 1695 and it was rebuilt and strengthened to serve primarily as a military base of operations. From Fort Frontenac in 1696 the French organized an attack on the Iroquois who inhabited areas south of Lake Ontario.[12]

Increased tension between the British and the French in the 1740s led to the French upgrading the fort's defensive capabilities by adding new guns, building new barracks and increasing the size of the garrison.[13] However, when the Marquis de Montcalm arrived at the fort in 1756 to launch an attack on the British at Oswego, he was not impressed with its construction. One of his engineers noted that:

The fort has a simple revetement of masonry, with poor foundations of small stones badly set, and the lime is bad; one could easily damage it with a sledge or a pick. The wall is about three to three and a half feet thick at the bottom and two at the top; it has been necessary to build walls for cover. The walls are from 20 to 25 feet high; there are no moats. The trees have been cut down within cannon-shot north and west and about two cannon-shots from the west to the south. ...As for the interior, a wooden scaffold has been built all around except along the north curtain where the commandant's house and chapel are, where the buildings are against the wall. This scaffold is too high; battlements have been let in on a level with the scaffold only eight inches high, which makes them useless. There are two openings for cannons on certain faces of the basions and one on the flanks. There are some places where the scaffold and even the wall would not stand cannon-fire long.[14]

The fort's strategic significance gradually decreased. Other forts such as Fort Niagara, Fort Detroit, and Fort Michilimackinac became more important.[15] By the 1750s Fort Frontenac essentially served only as a supply storage depot and harbour for French naval vessels, and its garrison had dwindled.

Battle of Fort Frontenac

During the Seven Years' War between Britain and France, who were vying for control of the North American continent, the British considered Fort Frontenac to be a strategic threat since it was in a position to command transportation and communications to other French fortifications and outposts along the St. Lawrence – Great Lakes water route and in the Ohio Valley. Although not as important as it once was, the fort was still a base from which the western outposts were supplied. The British reasoned that if they were to disable the fort, supplies would be cut off and the outposts would no longer be able to defend themselves. The Indian trade in the upper country (the Pays d'en Haut) would also be disrupted.[16]

Fort Frontenac was also regarded as a threat to Fort Oswego, which was built by the British across the lake from Fort Frontenac in 1722 to compete with Fort Frontenac for the Indian trade, and later enhanced as a military establishment. General Montcalm had already used Fort Frontenac as a staging point to attack the fortifications at Oswego in August 1756.

The British also hoped that taking the well-known fort would boost troop morale and honour after their demoralizing battle defeat at Fort Ticonderoga (Fort Carillon) in July 1758.[15][17]

In August 1758, the British under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel John Bradstreet left Fort Oswego with a force of a little over 3000 men and attacked Fort Frontenac. The fort's garrison of 110 men, including five officers and 48 enlisted men of the regular colonial troops, employees, women, children, 8 Indians, and others commanded by Pierre-Jacques Payen de Noyan et de Chavoy,[15] surrendered and were allowed to leave. Bradstreet captured the fort's supplies and nine French naval vessels, and destroyed much of the fort. He quickly departed to avoid further conflict with any French support troops.

For the British, Fort Oswego was secured, and the army's reputation was restored.[15] For the French, the fort's loss was considered to be only a temporary setback.[15] Fort Frontenac's surrender did not succeed in completely severing French communications and transportation to the west since other routes were available (e.g. the Ottawa River – Lake Huron route).[15] Supplies could also be moved west from other French posts (e.g. Fort de La Présentation).[15] In the long term, however, the surrender compromised French prestige among the Indians and contributed to the defeat of New France in North America.[18] Since the fort was no longer perceived to be important to the French, it was never rebuilt and was left abandoned for the next 25 years.[15]

French imperial power was waning in the late 1750s, and by 1763 France had withdrawn from the North American mainland. Cataraqui and the remains of Fort Frontenac were relinquished to the British.

Reconstruction and modern times

In 1783, the Cataraqui region was selected by the British as a location to settle United Empire Loyalists who had fled the United States after the American War of Independence. The centre of the region, a community focused on the old fort, would eventually become the city of Kingston. General Sir Frederick Haldimand, Governor of the Province of Quebec, ordered Major John Ross, commander at Oswego, to repair and rebuild the fort to accommodate a military garrison. This was done by a force of 422 men and 25 officers. By October 1783, a lime kiln, hospital, barracks, officers' quarters, storehouses, and a bakehouse were completed.[19] In 1787, the rebuilt fort became known as Tête-de-Pont Barracks.[20] During the War of 1812, the fort was the focus of military activity in Kingston, having housed many military troops. Many of the present barrack buildings were built between 1821 and 1824.[21][22]

After British imperial forces withdrew from most Canadian locations in 1870–71, the Canadian Militia authorized the creation of two batteries of garrison artillery which provided garrison duties and schools of gunnery. "A " Battery School of Gunnery was established at Tête-de-Pont Barracks and other locations in Kingston ("B " Battery was located in Quebec). These batteries were known as the Regiment of Canadian Artillery. When this regiment evolved into the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery (RCHA), its headquarters was at the Tête-de-Pont Barracks from 1905 to 1939. When the RCHA left for operational duties during the Second World War, the fort was used as a personnel depot.

On 25 May 1923, the site of Fort Frontenac was designated as a National Historic Site of Canada.

In 1939 the site of the fort again became known as Fort Frontenac. Canadian Army staff training began at Fort Frontenac when the Canadian Army Staff College moved to the fort from the Royal Military College in 1948. The college is now known as the Canadian Army Command and Staff College. Fort Frontenac was also the location of the National Defence College until 1994.

Archaeology

In 1982, archaeological investigation began at the fort. During the spring of 1984, the City of Kingston redesigned the intersection of Ontario and Place d'Armes Streets so that the northwest bastion (Bastion St. Michel) and curtain wall could be excavated and partially reconstructed. The research also provided important details about the development and use of the fort and surrounding area, and helped to establish the relationship between the physical remains and the information included in historical maps and plans.[23]

Intact remains of the east bastion were located in 2020 by archaeologists while preparing for infrastructure work. Deposits associated with the fur trade era were found on the south side of the bastion wall, including trade beads, beaver jaws, gun flints, and fish bones.[24]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Cataraqui Archaeological Research Foundation, Fort Frontenac Archived August 15, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2017-07-09

- ↑ Harris 1987, p. 87

- ↑ Mika 1987, pp. 9–12

- ↑ Osborne 2011, p. 9.

- ↑ Mika 1987, p. 9

- ↑ Osborne 2011, p. 151.

- ↑ The History of the Port of Kingston. Historic Kingston. Kingston Historical Society. 1954. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 2010-02-02

- ↑ Armstrong 1973, pp. 15, 16

- ↑ Finnigan 1976, p. 38.

- ↑ Parkman 1877, ch. VIII, pp. 140–142

- ↑ Adams 1986, pp. 10, 13

- ↑ Parkman 1877, ch. XIX, p. 410.

- ↑ Bazely 2007.

- ↑ Osborne 2011, pp. 14, 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Chartrand 2001.

- ↑ Anderson 2000, p. 264.

- ↑ Anderson 2000, p. 260.

- ↑ Biography of John Bradstreet

- ↑ Mika 1987, p. 21.

- ↑ Kingston Historical Society: Chronology of the History of Kingston Archived 2017-05-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 2013-07-14

- ↑ DND – Fort Frontenac Officers' Mess Archived 2011-06-08 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 2010-01-19

- ↑ DND – National Defence and the Canadian Forces – A History of Fort Frontenac Retrieved: 2015-02-22

- ↑ "Archaeology at Fort Frontenac". Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Archaeologists unearth the past at Kingston's Fort Frontenac. Global News". Retrieved August 17, 2020.

References

- Adams, Nick.Iroquois Settlement at Fort Frontenac in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries Archived September 13, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Ontario Archaeology, No. 46: 4–20. 1986. Retrieved 2013-02-19

- Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War – the Seven Years'War and the Fate of the Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Ltd., 2000. ISBN 0-375-40642-5.

- Armstrong, Alvin. Buckskin to Broadloom – Kingston Grows Up. Kingston Whig-Standard, 1973. No ISBN.

- Bazely, Susan M. Fort Frontenac: Bastion of the British. Kingston: Cataraqui Archaeological Research Foundation, 2007. Retrieved 2010-04-09

- Chartrand, René. Fort Frontenac 1758: Saving face after Ticonderoga. Osprey Publishing Military Books. 2001. (archived) Retrieved 2010-04-09

- Finnigan, Joan. Kingston: Celebrate This City. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Ltd., 1976. ISBN 0-7710-3160-2.

- Harris, R. Cole, Ed.Historical Atlas of Canada, From the Beginning to 1800. University of Toronto Press 1987. ISBN 0-8020-2495-5

- Mika, Nick and Helma et al. Kingston, Historic City. Belleville: Mika Publishing Co., 1987. ISBN 0-921341-06-7.

- Osborne, Brian S. and Donald Swainson. Kingston, Building on the Past for the Future. Quarry Heritage Books, 2011. ISBN 1-55082-351-5

- Parkman, Francis. Count Frontenac and New France Under Louis XIV, 4th Edition. Boston, 1877. Retrieved: 2010-04-09

- Godfrey, W. G. (1979). "Bradstreet, John". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- A History of Fort Frontenac Retrieved 2014-09-21

- Lamontagne, Leopold. Royal Fort Frontenac. Toronto: Champlain Society Publications, 1958.

External links

- Eccles, W. J. (1979) [1966]. "Buade de Frontenac et de Palluau, Louis de". In Brown, George Williams (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. I (1000–1700) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Eccles, W. J. (1979) [1969]. "Brisay de Denonville, Jacque-Rene de". In Hayne, David (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. II (1701–1740) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Dupré, Céline (1979) [1966]. "Cavelier Sieur de La Salle, René-Robert". In Brown, George Williams (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. I (1000–1700) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- La Roque de Roquebrune, R. (1979) [1966]. "Le Febvre de La Barre, Joseph-Antoine". In Brown, George Williams (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. I (1000–1700) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- The Cataraqui Archaeological Research Foundation – Fort Frontenac Archived August 15, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- The Founding Of Fort Frontenac

- Bradstreet, John. An impartial account of Lieut. Col. Bradstreet's expedition to Fort Frontenac : to which are added, a few reflections on the conduct of that enterprise, and the advantages resulting from its success. London. 1759

- McColloch, IM. Dominion of the Lakes? A Re-assessment of John Bradstreet's Raid on Fort Frontenac, 1758. Canadian Forces College. Archived.