| Fort Monroe | |

|---|---|

| Part of Harbor Defenses of Chesapeake Bay 1896–1945 | |

| Type | Headquarters, garrison fort, training center |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Federal, State, Local |

| Open to the public | Yes |

Fort Monroe National Monument | |

Fort Monroe in 2004 | |

| |

| Location | Hampton, Virginia |

| Coordinates | 37°00′13″N 76°18′27″W / 37.00361°N 76.30750°W |

| Area | 565 acres (229 ha) |

| Built | 1819–1834 |

| Architect | Simon Bernard[1] |

| Architectural style | Third system fort[1] |

| Website | Fort Monroe National Monument |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000912[2] (original) 13000708 (increase) |

| VLR No. | 114-0002 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Boundary increase | March 9, 2015 |

| Designated NHLD | December 19, 1960[3] |

| Designated NMON | November 1, 2011[4] |

| Designated VLR | September 9, 1969[5] |

| Site history | |

| Built by | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| In use | 1823–2011 |

| Materials | stone, brick, earth |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War World War I World War II |

Fort Monroe is a former military installation in Hampton, Virginia, at Old Point Comfort, the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula, United States. It is currently managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the National Park Service, and the city of Hampton as the Fort Monroe National Monument. Along with Fort Wool, Fort Monroe originally guarded the navigation channel between the Chesapeake Bay and Hampton Roads—the natural roadstead at the confluence of the Elizabeth, the Nansemond and the James rivers.

Until disarmament in 1946, the areas protected by the fort were the entire Chesapeake Bay and Potomac River regions, including the water approaches to the cities of Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland, along with important shipyards and naval bases in the Hampton Roads area. Surrounded by a moat, the six-sided bastion fort is the largest fort by area ever built in the United States.[6]

During the initial exploration by a mission headed by Captain Christopher Newport in the early 1600s, the earliest days of the Colony of Virginia, the site was identified as a strategic defensive location. Beginning by 1609, defensive fortifications were built at Old Point Comfort during Virginia's first two centuries. The first was a wooden stockade named Fort Algernourne, followed by other small forts.[7][8] However, the much more substantial facility of stone that became known as Fort Monroe (and adjacent Fort Wool on an artificial island across the channel) were completed in 1834, as part of the third system of U.S. fortifications. The principal fort was named in honor of U.S. President James Monroe.[9]

Although Virginia became part of the Confederate States of America, Fort Monroe remained in Union hands throughout the American Civil War (1861–1865). Union General George B. McClellan landed the Army of the Potomac at the fort during Peninsula campaign of 1862 of that conflict. The fort was notable as a historic and symbolic site of early freedom for former slaves under the provisions of contraband policies.

For two years following the war, the former Confederate President, Jefferson Davis, was imprisoned at the fort. His first months of confinement were spent in a cell of the casemated fort walls that is now part of its Casemate Museum.

Around the turn of the 20th century, numerous gun batteries were added in and near Fort Monroe under the Endicott program; it became the largest fort and headquarters of the Harbor Defenses of Chesapeake Bay.[8] In the 19th and 20th centuries it housed artillery schools, including the Coast Artillery School (1907–1946). The Continental Army Command (CONARC) (1955–1973) headquarters was at Fort Monroe, succeeded by the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) following a division of CONARC into TRADOC and United States Army Forces Command (FORSCOM) in 1973. CONARC was responsible for all active Army units in the continental United States. TRADOC was headquartered at the fort from 1973 until it was moved to Fort Eustis in 2011.[10]

Fort Monroe was deactivated September 15, 2011,[11] and many of its functions were transferred to nearby Fort Eustis. Several re-use plans for Fort Monroe are under development in the Hampton community. On November 1, 2011, President Barack Obama signed a proclamation to designate portions of Fort Monroe as a national monument. This was the first time that President Obama exercised his authority under the Antiquities Act, a 1906 law to protect sites deemed to have natural, historical or scientific significance.[4]

Description

Within the 565 acres of Fort Monroe are 170 historic buildings and nearly 200 acres of natural resources, including 8 miles of waterfront, 3.2 miles of beaches on the Chesapeake Bay, 110 acres of submerged lands and 85 acres of wetlands. It has a 332-slip marina and shallow water inlet access to Mill Creek, suitable for small watercraft.[12]

History

The land area where Fort Monroe is became part of Elizabeth Cittie [sic] in 1619, Elizabeth River Shire in 1634, and was included in Elizabeth City County when it was formed in 1643. Over 300 years later, in 1952, Elizabeth City County and the nearby Town of Phoebus agreed to consolidate with the smaller independent city of Hampton, which became one of the larger cities of Hampton Roads.

Colonial period

Arriving with three ships under Captain Christopher Newport, Captain John Smith and the colonists of the Virginia Company established the settlement of Jamestown and the British Colony of Virginia on the James River in 1607. On their initial exploration, they recognized the strategic importance of the site at Old Point Comfort for purposes of coastal defense. They initially built Fort Algernourne (1609–1622) at the location of the present Fort Monroe. It was renamed the Point Comfort Fort in 1612.[7] It is assumed to have been a triangular stockade, based on the fort at Jamestown. Other small forts known as Fort Henry and Fort Charles were built nearby in 1610 to protect the Kecoughtan settlement.[13] Fort Algernourne fell into disuse after 1622.[7]

In August 1619 a British-owned Dutch-flagged privateer, the White Lion, appeared off Old Point Comfort. Its cargo included between 20-30 Africans captured from the slave ship São João Bautista. Traded for work and supplies from the English, they were the first Africans to come ashore on British-occupied land in what would become the United States. The arrival of these Bantu people from Angola is considered to mark the beginning of slavery in colonial America.[14]

Another fort, known only as "the fort at Old Point Comfort" was constructed in 1632. In 1728, Fort George was built on the site. Its masonry walls were destroyed by a hurricane in 1749, but the wooden buildings in the fort were used by a reduced force from circa 1755 until at least 1775. During the American Revolutionary War, as Patriot and French forces approached Yorktown in 1781, the British established batteries on the ruins of Fort George. Shortly afterward, during the Siege of Yorktown, the French West Indian fleet occupied these batteries. Throughout the Colonial period, fortifications were manned at the location from time to time.[7]

Design and construction

Following the War of 1812, the United States realized the need to protect Hampton Roads and the inland waters from attack by sea. A British attack on Norfolk and Portsmouth was repulsed, but they then bypassed the existing fortifications and went on to burn Washington, D.C., and unsuccessfully attack Baltimore. In March 1819, President James Monroe's War Department came up with a plan of building a network of coastal defenses, later called the third system of U.S. fortifications. In 1822 construction began in earnest[15] on the stone-and-brick fort which would become the safeguard for Chesapeake Bay and the largest fort by area ever built in the United States.[7] It was intended as the headquarters for the third system of forts.[16] Among the original buildings is Quarters 1, designed as a residence and headquarters for Fort Monroe's commanding officer.[17] Work continued for nearly 25 years.[18]

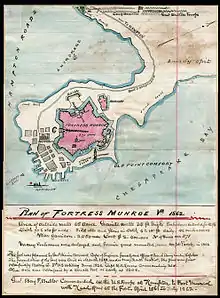

The fort was designed by brevet Brigadier General of engineers Simon Bernard, formerly a French brigadier general of engineers and aide to Napoleon, who had been banished from France after the latter's defeat at Waterloo in 1815, moved to the United States, and later commissioned as a brigadier general in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.[19] From the beginning of its construction until 1832 the fort's name was "Fortress Monroe", and it was sometimes referred to by that name subsequently.[7]

Fort Monroe was the first of the third system forts to begin construction, and was intended as a headquarters for the system as well as a fort. It is a bastion fort with an irregular hexagon shape and seven bastions. The southern and longest front is divided in two fronts by a bastion in the middle; the other bastions are at the corners. The fort is surrounded by a moat and covers 63 acres (25 ha). At the time it was built, the only land access to the fort's location was via a long, narrow isthmus to the north. A redoubt with a secondary moat was built northeast of the fort to guard against attack from this direction; the redoubt no longer exists, but the water gate for the secondary moat remains. The fort has a continuous barbette tier of cannon emplacements on the roof, but only a partial casemated tier in the fort, mainly on the southwestern and southern fronts. No positions for casemated flank howitzers exist on the northern and northwestern fronts (except two alongside the north sally port); this partial tier is unusual in the third system.[1] The main channel the fort protected was to the southeast; a casemated external battery (also called a "casemated coverface" or "water battery") of forty 42-pounder cannon[20] was built just outside the moat in this area.[1] This increased the number of cannon in this direction compared with casemated guns in the curtain wall from 28 to 40; it was accessed from the main fort via a bridge. As of 2018, only a small part of the external battery's north end remains, along with a salient place-of-arms just north of it with three gun positions.[1] The fort's walls were up to ten feet thick and the moat was eight feet deep. The initial design provided for up to 380 guns and was later expanded to 412 guns, intended for a garrison of 600 troops in peacetime and up to 2,625 troops in wartime. However, the fort was never fully armed.[8]

Early 19th century

The site of Fort Monroe was first garrisoned in June 1823 by Battery G of the 3rd U.S. Artillery Regiment[8] commanded by Captain Mann P. Lomax.

As a young first lieutenant and engineer in the U.S. Army, Robert E. Lee was stationed at the fort from 1831 to 1834 and played a major role in its final construction and its opposite, Fort Calhoun (renamed Fort Wool in 1862). He resided at Quarters 17.[21] Fort Calhoun was built on a man-made island called the Rip Raps across the navigation channel from Old Point Comfort in the middle of the mouth of Hampton Roads.[22] The Army briefly detained the Native American chieftain Black Hawk at Fort Monroe, following the 1832 Black Hawk War.

When construction was completed in 1834, Fort Monroe was referred to as the "Gibraltar of Chesapeake Bay." The fort mounted an impressive complement of powerful artillery: 42-pounder cannon with a range of over one mile. In conjunction with Fort Calhoun (later Fort Wool), this was just enough range to cover the main shipping channel into the area. (Decommissioned after World War II, the former Fort Wool on Rip Raps is now adjacent to the southern man-made island of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, first completed in 1957.)

From 1824 to 1946 Fort Monroe was the site of a series of schools of artillery. The first was the Artillery School of Practice. The school was closed in 1834 but was revived during the period 1858–61. It was succeeded by the Artillery School of the U.S. Army, which existed from 1867 until its redesignation in 1907 as the Coast Artillery School. Fort Monroe also hosted the Old Point Comfort Proving Ground for testing artillery and ammunition from the 1830s to 1861; after the Civil War this function relocated to the Sandy Hook Proving Ground in New Jersey.[7]

American Civil War

1860–61

Fort Monroe played an important role in the American Civil War. On December 20, 1860, South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union. Four months later, on April 12, 1861, troops of that state opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. Five days later, Virginia's legislature passed (subject to voters' ratification) the Ordinance of Secession of Virginia to withdraw from the Union and join the newly formed Confederate States of America. On 23 May 1861, voters of Virginia ratified the state's secession from the union.

President Abraham Lincoln had Fort Monroe quickly reinforced so that it would not fall to Confederate forces. It was held by Union forces throughout the Civil War, which launched several sea and land expeditions from there.

A few weeks after the Battle of Fort Sumter in 1861, U.S. Army General-in-Chief Winfield Scott proposed to President Abraham Lincoln a plan to bring the states back into the Union: Cut the Confederacy off from the rest of the world instead of attacking its army in Virginia. His Anaconda Plan was to blockade or occupy the Confederacy's coastline to limit the activity of blockade runners, and control the Mississippi River valley with gunboats. In cooperation with the Navy, troops from Fort Monroe extended Union control along the coasts of the Carolinas as Lincoln ordered a blockade of the southern seaboard from the South Carolina line to the Rio Grande on April 19 and, on April 27, extended it to include the North Carolina and Virginia coasts.

On April 20 the Union Navy burned and evacuated the Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth, destroying nine ships in the process, keeping Fort Monroe at Old Point Comfort as the last bastion of the United States in Tidewater Virginia. The Confederacy's occupation of Norfolk gave it a major shipyard and thousands of heavy guns, but they held it for only one year. Confederate Brigadier General Walter Gwynn, who commanded the Confederate defenses around Norfolk, erected batteries at Sewell's Point, to protect Norfolk and to control Hampton Roads.

The Union dispatched a fleet to Hampton Roads to enforce the blockade. On May 18–19, 1861, Federal gunboats based at Fort Monroe exchanged fire with the Confederate batteries at Sewell's Point. The little-known Battle of Sewell's Point resulted in minor damage to both sides. Several land operations against Confederate forces were mounted from the fort, notably the Battle of Big Bethel in June 1861.

On May 27, 1861, Major General Benjamin Butler made his famous "contraband" decision, or "Fort Monroe Doctrine", determining that the enslaved men who reached Union lines would be considered "contraband of war" (captured enemy property) and not be returned to bondage. Prior to this, the Union had generally enforced the Fugitive Slave Act, returning escaped slaves to their owners. The order resulted in thousands of slaves fleeing to Union lines around Fort Monroe, which was Butler's headquarters in Virginia. Fort Monroe became called "Freedom's Fortress", as any self-emancipating person reaching it would be free. In the Summer of 1861 Harry Jarvis made his way to Fort Monroe and insisted General Butler let him enlist. Butler refused because he believed "it wasn't a black man's war." Jarvis replied, "It would be a black man's war," due to the presence of the incoming of thousands of runaway slaves. This marked a sudden shift in the war.[23] In March 1862 Congress passed a law formalizing this policy. By the fall, the Army had built the Great Contraband Camp in Hampton to house the families. It was the first of more than 100 that would be established by war's end, and the Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony (1863–1867), which started as a contraband camp. Many contrabands were employed by the Union Army in support roles such as cooks, wagon drivers, and laborers. Beginning in January 1863, the United States Colored Troops were formed, with many contrabands enlisting; these units were composed primarily of white officers and African-American enlisted men, and eventually numbered nearly 180,000 soldiers.[24]

Mary S. Peake was teaching the children of freedmen to read and write near Fort Monroe. She was the first black teacher hired by the American Missionary Association (AMA), a northern missionary group led by black and white ministers from the Congregational, Presbyterian and Methodist denominations, who strongly supported education of freedmen. Soon she was teaching children during the day and adults at night. The AMA sponsored hundreds of northern teachers and hired local teachers in the south; it founded more than 500 local schools and 11 colleges for freedmen and their children.

During the Civil War Fort Monroe was the site of a military balloon camp under the flight direction of aeronaut John LaMountain. The Union Army Balloon Corps was being developed at Fort Corcoran near Arlington under the presidentially appointed Prof. Thaddeus S. C. Lowe. At the same time, LaMountain, who was vying for position as Chief Aeronaut, had gained the confidence of Butler in using his balloon Atlantic for aerial observations. LaMountain is credited with having made the first successful report from an aerial station that was of practical military intelligence. LaMountain was later reassigned to Lowe's balloon corps, but after a period of in-fighting with Lowe, he was released from military service. Lowe eventually assigned regular military balloons to Fort Monroe.

In 1861 the prototype 15-inch Rodman gun was delivered to Fort Monroe and was subsequently fired 350 times in testing. This weapon (Fort Pitt Foundry No. 1 of 1861) is displayed at the fort as of 2018; a plaque states that it was test fired for President Lincoln and was nicknamed the "Lincoln gun". This type of weapon was deployed for coastal defense during the war (an 1862 map shows an external battery of them at Fort Monroe) and more widely deployed following the war.[25]

1862

In March 1862, the naval Battle of Hampton Roads took place off Sewell's Point between two early ironclad warships, CSS Virginia and USS Monitor. While the outcome was inconclusive, the battle marked a change in naval warfare and the end to wooden fighting ships.

Later that spring, the continuing presence of the Union Navy based at Fort Monroe enabled federal water transports from Washington, D.C., to land unmolested to support Major General George B. McClellan's Peninsula Campaign. Formed at Fort Monroe, McClellan's troops moved up the Virginia Peninsula during the spring of 1862, reaching within a few miles of the gates of Richmond about 80 miles to the west by June 1. For the next 30 days, they laid siege to Richmond. Then, during the Seven Days Battles, McClellan fell back to the James River well below Richmond, ending the campaign. Fortunately for McClellan, during this time, Union troops regained control of Norfolk, Hampton Roads, and the James River below Drewry's Bluff (a strategic point about 8 miles south of Richmond).

Beginning in 1862 Fort Monroe was also used as a transfer point for mail exchange. Mail sent from states in the Confederacy addressed to locations in the Union had to be sent by flag-of-truce and could only pass through at Fort Monroe where the mail was opened, inspected, resealed, marked and sent on. Prisoner of war mail from Union soldiers in Confederate prisons was required to be passed through this point for inspection.[26][27]

1864–1867

In 1864, the Union Army of the James under Major General Benjamin Butler was formed at Fort Monroe. The 2nd Regiment, United States Colored Cavalry, mustered in at Fort Monroe on December 22, 1864,[28] and the 1st Regiment, United States Colored Cavalry mustered in the same day at nearby Camp Hamilton.[29] The Siege of Petersburg during 1864 and 1865 was supported on the James River from a base at City Point (now Hopewell, Virginia). Maintaining the control of Hampton Roads at Fort Monroe and Fort Wool was crucial to the naval support Grant required for the successful Union campaign to take Petersburg, which was the key to the fall of the Confederate capital at Richmond. As Petersburg fell, Richmond was evacuated in 1865 on the night of April 2–3. That night, Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet escaped Richmond, taking the Richmond and Danville Railroad to move first to Danville and then North Carolina. However, the cause was lost, and Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered what was left of the Army of Northern Virginia to Grant at Appomattox Court House the following week.

After the last Confederate cabinet meeting was held on April 26, 1865, at Charlotte, North Carolina, Jefferson Davis was captured at Irwinville, Georgia, and placed under arrest. Davis was confined for two years at Fort Monroe, beginning on May 22, 1865. For a few days he was confined in irons; newspaper accounts of this beginning on May 27 aroused sympathy for him, even in the North, and Union secretary of war Edwin M. Stanton soon ordered the irons removed. At the fort, Union surgeon John J. Craven had already recommended this, and continued to recommend better quarters, access to tobacco, and freedom of movement for Davis.[30] In poor health, Davis was released in May, 1867, on bail, which was posted by prominent citizens of both Northern and Southern states, including Horace Greeley and Cornelius Vanderbilt, who had become convinced he was being treated unfairly. The federal government proceeded no further in its prosecution due to the constitutional concerns of U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase. Davis died in 1889.

Post-Civil War and early Endicott Period (1868–1906)

.jpg.webp)

The Journal of the United States Artillery was founded at Fort Monroe in 1892 by First Lieutenant (later General) John Wilson Ruckman and four other officers of the Artillery School.[31] Ruckman served as the editor of the Journal for four years (July 1892 to January 1896) and published several articles therein afterward. One publication by West Point notes Ruckman's "guidance" and "first-rate quality" work were obvious as the Journal "rose to high rank among the service papers of the world". The Journal was renamed the Coast Artillery Journal in 1922[32] and the Antiaircraft Journal in 1948.[33]

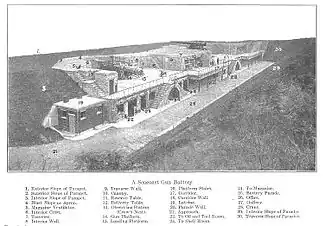

The Board of Fortifications, chaired by Secretary of War William C. Endicott and often called the Endicott board, met in 1885 to consider the future of U.S. coast defenses. In 1886 the board's report recommended an across-the-board improvement program, often called the Endicott program. This included replacing all existing weapons with modern breech-loading guns and mortars in reinforced concrete batteries with earth cover and providing controlled minefields in ship channels.[34] Fort Monroe was to be one of the largest installations of this program, and in 1896 construction began on new gun batteries there. The fort was the headquarters and main fort of the Coast Defenses of Chesapeake Bay, which was organized circa 1896 as an artillery district and redesignated in 1913.[8][35]

By 1906 the following batteries were completed:[8][36]

| Name | No. of guns | Gun type | Carriage type | Years active | Condition in 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson | 8 | 12-inch (305 mm) mortar M1890 | barbette M1896 | 1898–1943 | intact |

| Ruggles | 8 | 12-inch (305 mm) mortar M1890 | barbette M1896 | 1898–1943 | intact |

| De Russy | 3 | 12-inch (305 mm) gun M1895 | disappearing M1897 | 1904–1944 | intact, earth glacis removed |

| Parrott | 2 | 12-inch (305 mm) gun M1900 | disappearing M1901 | 1906–1943 | intact, 90 mm gun in place |

| Humphreys | 1 | 10-inch (254 mm) gun M1888 | disappearing M1894 | 1897–1910 | demolished |

| Eustis | 2 | 10-inch (254 mm) gun M1888 | disappearing M1896 | 1901–1942 | demolished |

| Church | 2 | 10-inch (254 mm) gun M1895 | disappearing M1896 | 1901–1942 | intact, earth glacis removed |

| Bomford | 2 | 10-inch (254 mm) gun M1888 | disappearing M1894 | 1897–1942 | demolished |

| Northeast bastion (experimental) | 1 | 10-inch (254 mm) gun M1896 | disappearing M1894 | 1900–1908 | intact |

| Barber | 1 | 8-inch (203 mm) gun M1888 | barbette M1892 | 1898–1913 | demolished |

| Parapet | 2 | 8-inch (203 mm) gun M1888 | barbette M1892 | 1898–1915 | mostly buried |

| Montgomery | 2 | 6-inch (152 mm) gun M1900 | pedestal M1900 | 1904–1948 | demolished |

| Gatewood | 4 | 4.72-inch Armstrong gun | pedestal | 1898–1914 | mostly buried |

| Irwin | 4 | 3-inch (76 mm) gun M1898 | masking parapet M1898 | 1903–1920 | intact, two 3-inch M1902 guns in place |

Battery Gatewood and the northeast bastion battery were built on the roof of the old fort's southeastern front and bastion; the parapet battery was on the roof of the eastern half of the old fort's southern side. The parapet battery had four emplacements, but only two of these had guns.[37] Batteries Bomford and Barber were north of the old fort. Battery Humphreys was immediately northeast of the old fort and oriented southeast.[38] Batteries Irwin and Parrott were in front of the old fort's southern side. The remaining batteries were on the isthmus extending north from the old fort in this order: Eustis, De Russy, Montgomery, Church, Anderson/Ruggles. Batteries Anderson and Ruggles were a line of four open-back mortar pits, originally with four mortars in each pit. Battery Anderson was the southern pair of pits and Battery Ruggles was the northern pair. Originally all four pits were named Anderson, but they were divided into two batteries in 1906.[8][39][40]

Battery Gatewood and the parapet battery were among a number of batteries begun after the outbreak of the Spanish–American War in 1898. Most of the Endicott batteries were years from completion, and most existing defenses still had muzzle-loading weapons. It was feared that the Spanish fleet might bombard U.S. east coast ports. Modern quick-firing guns were acquired from the United Kingdom and installed in new batteries. Battery Gatewood had four 4.72-inch/50 caliber guns while the parapet battery had four platforms for 8-inch M1888 guns with only two guns mounted.[41][42] The northeast bastion battery was built to test an experimental 10-inch M1896 "depressing gun"; the battery was disarmed in 1908.[43] Battery Humphreys was disarmed in 1910; batteries Barber, Gatewood, and the parapet battery were disarmed in 1913–1915.[8]

Fire control towers to direct the use of guns and mines were also built at the fort.[7][8]

During the Spanish–American War Fort Monroe also hosted the Camp Josiah Simpson Army General Hospital, including the post hospital and a tent camp on the old fort's parade ground.[7]

Twentieth century

The Jamestown Exposition, held in 1907 at Hampton Roads, featured an extensive naval review, including the Great White Fleet. Beginning in 1917, the former exposition site at Sewell's Point became a major base of the United States Navy. Currently, Naval Station Norfolk is the base supporting naval forces operating in the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and Indian Ocean. As of 2018, it is the world's largest naval station by number of military members supported.

World War I

During World War I, Fort Monroe and Fort Wool were used to protect Hampton Roads and the important inland military and civilian resources of the Chesapeake Bay area as part of the Coast Defenses of Chesapeake Bay. The fort installed the first anti-submarine net in America in February 1917 stretching to Fort Wool. Although many guns were removed from coast defenses in World War I for potential service as field guns and railway artillery, this did not happen with most weapons at Fort Monroe due to its strategic importance. However, eight mortars were removed from Battery Anderson-Ruggles for potential overseas service and to improve the rate of fire of the remaining weapons; five of the removed mortars became railway artillery in France; it is unclear if they were used in action.[40][44] Battery Montgomery's pair of pedestal-mounted 6-inch (152 mm) guns were relocated to a temporary battery at Cape Henry in 1917; they were replaced with weapons of the same type in February 1919.[45] Fort Monroe was also important as a mobilization and training center; the Coast Artillery Corps operated the weapons removed from forts along with most other US-manned heavy and railway artillery on the Western Front.[46] In 1918 Camp Eustis (now Fort Eustis) was established near Newport News as a coast artillery replacement center to relieve overcrowding at Fort Monroe.[47] During World War I the authorized strength of the Coast Defenses of Chesapeake Bay was 17 companies, including five from the Virginia National Guard.[48]

Interwar period

In 1922 Fort Monroe's importance in defending Chesapeake Bay was somewhat reduced with the establishment of a battery of four 16-inch (406 mm) howitzers at Fort Story on Cape Henry, at the entrance to the bay. With the improved weapon location and a range advantage over Fort Monroe's 12-inch guns of 24,500 yards (22,400 m) versus 18,400 yards (16,800 m), the 16-inch weapons could engage attacking warships long before they could come within range of Fort Monroe.[49][50] In 1920 Battery Irwin's four 3-inch (76 mm) guns were removed as part of a general removal from service of M1898 3-inch guns; they were not replaced until 1946, when the battery became a saluting battery.[51] In 1924 the Coast Artillery Corps' harbor defense garrisons transitioned from a company-based organization to a regimental organization. The Harbor Defenses of Chesapeake Bay (as renamed in 1925) were garrisoned by the 12th Coast Artillery Regiment of the regular army,[52] with the 246th Coast Artillery Regiment as the Virginia National Guard component.[53] In 1932 the 12th Coast Artillery was effectively redesignated as the 2nd Coast Artillery, continuing as the garrison of Chesapeake Bay.[54]

World War II

During World War II, Fort Monroe continued as headquarters for the Harbor Defenses of Chesapeake Bay. However, during the war new 16-inch (406 mm) gun batteries were built at Fort Story and at Fort John Custis on Cape Charles.[55] These rendered Fort Monroe's heavy guns obsolete, and between 1942 and 1944 all of the fort's 10-inch (254 mm) and 12-inch (305 mm) guns and mortars were scrapped. However, the two rapid-fire 6-inch (152 mm) guns of Battery Montgomery remained until 1948. A 16-inch (406 mm) gun battery of two guns (Battery 124) was proposed for Fort Monroe but not built. A new Anti-Motor Torpedo Boat (AMTB) battery (AMTB 23) was built in 1943, with two fixed, dual-purpose (anti-surface and anti-aircraft) 90 mm guns at the old Battery Parrott, which was partly rebuilt to accommodate them.[8] This type of battery was usually authorized two fixed and two mobile 90 mm guns and two 37 mm or 40 mm guns, but it is unclear where the additional weapons were located. In addition, submarine barriers and underwater mine fields continued to be controlled from Fort Monroe. But by the end of the Second World War, the vast array of armaments guarding the Chesapeake was made largely obsolete due to the development of the long-range bomber and the refinement of naval aviation. Essentially all of the United States' coast defense guns were scrapped by the end of 1948.[56]

Post World War II

Since World War II, Fort Monroe has been a major Army training headquarters. However, in 1946 the Coast Artillery School relocated to Fort Winfield Scott in San Francisco, where it was disestablished in 1949; the remnant of the Coast Artillery Corps was also disestablished a year later.[7] Also in 1946 Battery Irwin became a saluting battery with two 3-inch M1902 guns relocated from Fort Wool, which are still in place.[8] The fort also hosted some Cold War antiaircraft defenses in the 1950s; a battery of four 90 mm guns 1953–55 (site N-03) and a Nike missile battery headquarters 1955–60 (site N-08).[7] The Continental Army Command (CONARC) headquarters was at Fort Monroe throughout its existence from 1955 to 1973. CONARC was responsible for all active Army units in the continental United States, and in 1973 was split into the United States Army Forces Command (FORSCOM) and the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC). The latter command was headquartered at the fort from 1973 until the fort's decommissioning in 2011.[10] At the turn of the 21st century, Fort Monroe supported a work population of some 3,000, including 1,000 people in uniform.

Hotels at Fort Monroe

In 1822 the Hygeia Hotel was built to accommodate some of the fort's builders. It eventually expanded to 200 rooms. In 1862 it was torn down by orders of the Secretary of War to limit civilian access to the post in wartime. It was replaced with a hotel of the same name after the war, and in 1874 became managed by Harrison Phoebus, for whom the city of Phoebus was named following his death in 1886. The second Hygeia Hotel was torn down in 1902 to make room for the fort's expansion under a new fortifications program. By this time the Chamberlin Hotel (built 1896) was in business; this building burned down and was replaced with the current building in 1928.[57] It now serves as a retirement community for those 55 years and older.

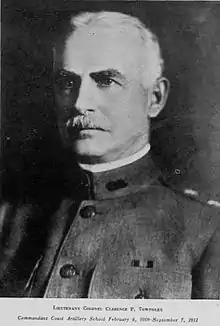

Coast Artillery School

In 1907 the Coast Artillery School was established along with the U.S. Army Coast Artillery Corps. New buildings were constructed for classrooms and barracks, with the library and school buildings completed in 1909.[58] As part of the school's responsibility the Journal of the United States Artillery (renamed Coast Artillery Journal in 1922) was published under the supervision of the commandant.[32] The school operated until 1946 when most of the coast artillery was disbanded, and the school was moved to Fort Winfield Scott in San Francisco.

.jpg.webp)

Commandants list

| Image | Rank | Name | Begin Date | End Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lieutenant colonel | Ramsay D. Potts | 22 February 1904 | 11 August 1906 | [a] |

| Lieutenant colonel | George F. E. Harrison | 24 October 1906 | 14 January 1909 | [a] |

| Lieutenant colonel | Clarence Page Townsley | 6 February 1909 | 7 September 1911 | [a] |

| Lieutenant colonel | Frederick S. Strong | 8 September 1911 | 27 February 1913 | [a] |

| Colonel | Ira A. Haynes | 18 February 1913 | 16 October 1916 | [a] |

| Colonel | Stephen M. Foote | 1 October 1916 | 23 August 1917 | [a] |

| Colonel | John A. Lundeen | 23 August 1917 | 30 March 1918 | [a] |

| Colonel | Frank K. Fergusson | 30 March 1918 | 11 September 1918 | [a] |

| Colonel | Robert R. Welshimer | 8 September 1918 | 29 January 1919 | [a] |

| Colonel | Eugene Reybold | 29 January 1919 | 19 January 1920 | [a] |

| Colonel | Jacob C. Johnson | 19 January 1920 | 3 November 1920 | [a] | |

| Colonel | Richmond P. Davis | 28 April 1921 | 28 December 1922 | [a] |

| Brigadier General | William Ruthven Smith | 11 January 1923 | 20 December 1924 | [a] |

| Brigadier General | Robert Emmet Callan | 20 December 1924 | 3 June 1929 | [a] |

| Brigadier General | Henry D. Todd Jr. | 28 August 1929 | 31 August 1930 | [a] |

| Brigadier General | Stanley Dunbar Embick | 1 October 1930 | 25 April 1932 | [a] |

| Brigadier General | Joseph P. Tracy | 31 August 1932 | 1 December 1936 | [a] |

| Brigadier General | John W. Gulick | 3 January 1937 | 12 October 1938 | [a] |

| Brigadier General | Frederick H. Smith | 21 November 1938 | 1 October 1940 | [a] | |

| Brigadier General | Frank S. Clark | 10 October 1940 | 15 January 1942 | [a] | |

| Brigadier General | Lawrence B. Weeks | 15 January 1942 | 1 October 1945 | [a] | |

| Brigadier General | Robert T. Frederick | 1 November 1945 | 19 August 1947 | [a] |

Base Realignment and Closure

The 2005 Base Realignment and Closure Commission of the Department of Defense released a list on 13 May 2005 of military installations recommended for closure or realignment, among which was Fort Monroe. The list was approved by President George W. Bush on 15 September 2005 and submitted to Congress. Congress failed to act within 45 legislative days to disapprove the list in its entirety, and the BRAC recommendations subsequently became law. Installations on the BRAC list were required by law to close within six years, and Fort Monroe ceased to be an Army post in 2011. Many of its functions were transferred to nearby Fort Eustis, which was named for Fort Monroe's first commander, General Abraham Eustis, a noted artillery expert.

Preservation

Fort Monroe has become a popular historical site. The Casemate Museum, opened in 1951, depicts the history of Fort Monroe and Old Point Comfort, with special emphasis on the Civil War period. It offers a view of Confederate President Jefferson Davis' prison cell. Also shown are the quarters occupied by 1st Lt. Robert E. Lee in 1831–34, and the quarters where President Abraham Lincoln was a guest in May 1862. Most of the other historic officers' quarters and other buildings are also preserved. A uniform of the renowned American writer Edgar Allan Poe, who was stationed there in 1828 serving as an artillery regimental command sergeant major, is also on display.

Several historic weapons were preserved at the fort as of 2005. The 15-inch Rodman prototype "Lincoln gun" was on the parade. A 90 mm gun on a dual-purpose coast defense mount remained at Battery Parrott, and two 3-inch M1902 seacoast guns remained at Battery Irwin as of 2015.[59] A 75 mm gun (nicknamed a "French 75" and used by the field artillery in World War I through early World War II) was at the new officers' club in the northern part of the reservation in 2005. The fort's last fire control tower was demolished in late 2001.[7] Batteries Irwin, Parrott, De Russy, the northeast bastion battery, and Battery Anderson/Ruggles are intact as of 2018, though the seaward earth cover has been removed from some of them.[8]

Redevelopment

The Fort Monroe Federal Area Development Authority (FMFADA) (renamed the Fort Monroe Authority as of 2019)[60] was established in 2007 by legislative action of the Virginia General Assembly as a public body corporate and as a political subdivision of the Commonwealth of Virginia, to serve as the official Local Redevelopment Authority (LRA) recognized by the Department of Defense. The task of the FMFADA commission was to study, plan, and recommend the best use of the resources that remain when the Army closed the fort in September 2011. The Fort Monroe Reuse Plan was officially adopted August 2008.[61] The FMFADA relies on the expertise of national consultants in the areas of BRAC law, environmental engineering, historic architecture and preservation planning, structural engineering, housing market analysis, commercial/retail analysis, public relations/marketing, and tourism planning.

The Virginia Department of Historic Resources and the Department of Environmental Quality have major regulatory authority that influences the work. The state took a lead role in planning because most of the land that Fort Monroe occupies will revert to the Commonwealth when the Army closes the fort. The effort was guided by three priorities — keep Fort Monroe open to the public, respect the rich history, and advance economic sustainability.

The Authority is an 18-member body consisting of appointees from the city of Hampton, the Virginia House of Delegates and Senate and the Virginia governor's cabinet, with two specialists in historic preservation and heritage tourism.

Virginia historically has given local government strong consideration in determining disposition at that point, such as occurred at Fort Pickett in Nottoway County (near Blackstone) in the Southside region. Given the historic significance of the post, the decommissioned fort will be a good candidate for heritage tourism along with many other historical sites throughout the greater Hampton Roads area. Redevelopment to help offset the economic loss of a base closure is a priority.

Fort Monroe is a National Historic Landmark and the moated fort and the 190 historic buildings on Old Point Comfort will be protected with historic preservation design guidelines for reuse. Old Point Comfort is prime development property and some mixed used new construction will be allowed within strict guidelines. For example, before the Army left, the historic Chamberlin Hotel had already been beautifully renovated as a community of retirement apartments.

The National Park Service and the Fort Monroe FADA have been communicating to identify the best way to achieve a partnership and the park service presented several options.[62] In 2013, Governor Bob McDonnell approved a new master plan to revitalize the site and the National Trust for Historic Preservation cited the site as one of ten historic sites saved that year.[63] By August 2014 only two businesses had moved in.[64]

Fort Monroe Authority operates leases for commercial properties and residences at the former post. Currently, homes are only available to lease.

There are several businesses now operating at Fort Monroe, including Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), a YMCA, three restaurants and a brewery. The Fort Monroe Authority also oversees event rentals to the public at the Commander General's house and the bandstand.

The beaches are open to the public. The main general parking is located at Outlook Beach.

National monument and historical interpretation

On November 1, 2011, President Barack Obama signed a proclamation to designate portions of Fort Monroe as a national monument. This was the first time that President Obama exercised his authority under the Antiquities Act, a 1906 law to protect sites deemed to have natural, historical or scientific significance.[4]

Fort Monroe National Monument released its finalized foundation document in 2015.[65] The National Park Service works with the Fort Monroe Authority on programming and maintenance.

Eola Lewis Dance is the Acting Superintendent,[66] supported by Ranger Aaron Firth. Terry E. Brown (2016-2020) and Kirsten Talken-Spaulding (2011-2016) also have served as Fort Monroe Superintendents.

A Visitors and Education Center[67] has been developed in the former Coast Artillery School Library, and is located at 30 Ingalls Road, next to the former Post Office that houses the offices for the Fort Monroe Authority. The building was designed by architect Francis B. Wheaton.

The building had a soft opening in 2019 and opened, briefly, to the public in 2020. Its grand opening has been put on hold during the pandemic. The center houses exhibits that focus on the history of the fort. It also features public restrooms, a bookstore and, on the second level, archives.

New walking tour markers and a brochure have been developed to help visitors better navigate the inner and outer fort.

1619 African Landing and commemoration

Fort Monroe is noted as the location of the arrival of the first Africans to English-speaking North America. It was recorded "20 and odd" enslaved Africans were brought to Point Comfort, Virginia, in August 1619 on the White Lion. The enslaved were traded for provisions and marked the beginning of slavery in the colony.[68]

In 2019, Fort Monroe hosted multiple programs associated with commemorating African arrival in 1619.[69] The 400th anniversary was marked by a Day of Healing and Nationwide Bell Ringing. One of the lives focused on during the commemoration was that of Angela, an enslaved woman owned by William Peirce.[70]

A memorial to the African Landing is currently being designed by the Fort Monroe Authority.

Fort Monroe was designated as a Site of Memory with UNESCO's Slave Route Project in February 2021.[71]

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Fort Monroe has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[72]

See also

- Chapel of the Centurion

- Quarters 1

- Quarters 17

- Seacoast defense in the United States

- List of coastal fortifications of the United States

- List of Underground Railroad sites

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Virginia

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Hampton, Virginia

- List of national monuments of the United States

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Weaver II 2018, pp. 179–186.

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ↑ "Fort Monroe". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2007-12-29. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- 1 2 3 Macauley, David (1 Nov 2011). "It's Official - President Obama confirms Fort Monroe park designation". Daily Press. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ↑ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ Weaver II 2018, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Hampton Roads forts at American Forts Network

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Fort Monroe at FortWiki.com

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 129.

- 1 2 FAQ at TRADOC.army.mil

- ↑ "Fort Monroe Stands Down After 188 Years of Army Service". The Daily Press. 15 September 2011. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ↑ "Archived copy of Fort Monroe Authority description". Archived from the original on 2011-03-08. Retrieved 2011-05-27.

- ↑ "Hampton Roads Area - Early Hampton Forts". American Forts Network. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ Waxman, Olivia B. (August 20, 2019). "Where the Landing of the First Africans in English North America Really Fits in the History of Slavery". Time. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- ↑ Konstam, Angus & Spedaliere, Donato: American Civil War Fortifications (1): Coastal brick and stone forts, p.19; Osprey Publishing, 2013

- ↑ Weaver II 2018, pp. 41, 179–186.

- ↑ Katherine D. Klepper (December 2009). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Quarters 1" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- ↑ "Fort Monroe During the Civil War". Kenmore Stamp Company. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ↑ Weaver II, John R. (2018). A Legacy in Brick and Stone: American Coastal Defense Forts of the Third System, 1816-1867, 2nd Ed. McLean, VA: Redoubt Press. pp. 179–186. ISBN 978-1-7323916-1-1.

- ↑ Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

- ↑ Katherine D. Klepper (n.d.). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Quarters 17" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- ↑ Weaver II 2018, pp. 186–190.

- ↑ Hahn, Steven. The Nathan I. Huggins Lectures : The Political Worlds of Slavery and Freedom. Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press, 2009. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 16 October 2016.Copyright © 2009. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Gladstone, Gladstone, William A. (1990). United States Colored Troops, 1863–1867. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications. pp. 9, 120. ISBN 0-939631-16-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ripley, Warren (1984). Artillery and Ammunition of the Civil War. Charleston, S.C.: The Battery Press. p. 80. OCLC 12668104.

- ↑ "Civilian Flag-of-Truce Covers". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ↑ "Prisoner mail exchange". Prisoner of War mail, Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ↑ 2nd Regiment, United States Colored Cavalry at CivilWarArchive.com

- ↑ 1st Regiment, United States Colored Cavalry at CivilWarArchive.com

- ↑ Erickson, Mark St. John (May 19, 2017). "Civil War 150: Jefferson Davis begins imprisonment at Fort Monroe". Daily Press. Norfolk, VA. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ↑ Journal of the United States Artillery, vol. XX, 1903

- 1 2 "Coast Artillery Journal at sill-www.army.mil". Archived from the original on 2018-05-17. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

- ↑ "Antiaircraft Journal at sill-www.army.mil". Archived from the original on 2019-02-08. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- ↑ "U.S. Seacoast Defense 1781-1948: A Brief History". Coast Defense Study Group. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ↑ "Coast Artillery Organization, A Brief Overview, p. 421" (PDF). Coast Defense Study Group. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ↑ Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2015). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide (Third ed.). McLean, Virginia: CDSG Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-9748167-3-9.

- ↑ Battery Parapet at FortWiki.com

- ↑ Battery Humphreys at FortWiki.com

- ↑ 1921 maps of Fort Monroe at CDSG.org (PDF file)

- 1 2 Battery Anderson at FortWiki.com

- ↑ Gun and Carriage cards, National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 156, Records of the Chief of Ordnance, Entry 712

- ↑ In The War With Spain, United States. Commission Appointed by the President to Investigate the Conduct of the War Dept (1900). "Congressional serial set, 1900, Report of the Commission on the Conduct of the War with Spain, Vol. 7, pp. 3778-3780, Washington: Government Printing Office". Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ↑ Northeast bastion battery at FortWiki.com

- ↑ US Army Railway Artillery, WWI at Rootsweb.com

- ↑ Battery Montgomery (2) at FortWiki.com

- ↑ History of the Coast Artillery Corps in World War I at Rootsweb.com

- ↑ Fort Eustis at FortWiki.com

- ↑ Rinaldi, Richard A. (2004). The U. S. Army in World War I: Orders of Battle. General Data LLC. p. 165. ISBN 0-9720296-4-8.

- ↑ Fort Story at FortWiki.com

- ↑ Berhow 2015, p. 61.

- ↑ Battery Irwin at FortWiki.com

- ↑ Gaines, William C., Coast Artillery Organizational History, Regular Army regiments, 1917-1950, Coast Defense Journal, vol. 23, issue 2, p. 10

- ↑ National Guard Coast Artillery regiment histories at the Coast Defense Study Group

- ↑ Gaines regular army, p. 5

- ↑ The Harbor Defenses of Chesapeake Bay at CDSG.org

- ↑ Lewis 1979, p. 132.

- ↑ Hotels at Point Comfort/Fort Monroe at VirginiaPlaces.org

- ↑ Annual Report of the Commandant, Coast Artillery School, 1916, Appendix C, pp. 31–32

- ↑ Berhow 2015, pp. 240–241.

- ↑ Fort Monroe Authority website

- ↑ "Fort Monroe Federal Area Development Authority". n.d. Archived from the original on 2010-03-10.

- ↑ "Making the case for Fort Monroe". Hamptonroads.com. The Virginian Pilot. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ Fort Monroe Master Plan Approved at National Trust for Historic Preservation

- ↑ Robert Brauchle. "Businesses slow to move to Fort Monroe". Daily Press. Archived from the original on 2014-09-15. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ↑ "Fort Monroe National Monument Foundation Document Overview" (PDF). 2015.

- ↑ Monroe, Mailing Address: 41 Bernard Road Building #17 Fort; Us, VA 23651-1001 Phone: 757-722-FORTContact. "Park Management - Fort Monroe National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Fort Monroe Visitor and Education Center (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Monroe, Mailing Address: 41 Bernard Road Building #17 Fort; Us, VA 23651-1001 Phone: 757-722-FORTContact. "History & Culture - Fort Monroe National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Reid, L. Chardé (2021-02-23). ""It's Not About Us": Exploring White-Public Heritage Space, Community, and Commemoration on Jamestown Island, Virginia". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 26: 22–52. doi:10.1007/s10761-021-00593-9. ISSN 1573-7748. S2CID 233964297.

- ↑ "Angela (fl. 1619–1625) – Encyclopedia Virginia". 2021-05-28. Archived from the original on 2021-05-28. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ↑ "Fort Monroe receives global recognition". 13newsnow.com. 20 February 2021. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Climate Summary for Fort Monroe

External links

- Fort Monroe National Monument

- Fort Monroe Casemate Museum

- Fort Monroe Authority website

- Map of HD Chesapeake Bay at FortWiki.com

- American Forts Network, lists forts in the US, former US territories, Canada, and Central America

- List of all US coastal forts and batteries at the Coast Defense Study Group, Inc. website

- Google Earth KML File

- "How Slavery Really Ended in America" by Adam Goodheart, The New York Times, April 1, 2011

- Reese, Franklin W., "U.S. Hotel Chamberlin", Coast Artillery Journal, March-April 1942, Vol. 85, No. 2, pp. 52–54 Archived 2020-10-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Archival Records

- "Fort Monroe Records at the Library of Virginia", at Virginia Memory

- Fort Monroe film clips at CriticalPast.com

- The short film Big Picture: Historic Fort Monroe is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Fort Monroe, Hampton, Hampton, VA: 71 photos, 7 measured drawings, 37 data pages, and 4 photo caption pages at Historic American Buildings Survey

- Fort Monroe, Fortress, Hampton, Hampton, VA: 57 photos, 5 color transparencies, and 6 photo caption pages at Historic American Buildings Survey