| |

France |

Italy |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of France, Rome | Embassy of Italy, Paris |

International relations between France and Italy occur on diplomatic, political, military, economic, and cultural levels, officially the Italian Republic (since 1946), and its predecessors, the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia (1814–1861) and the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946).

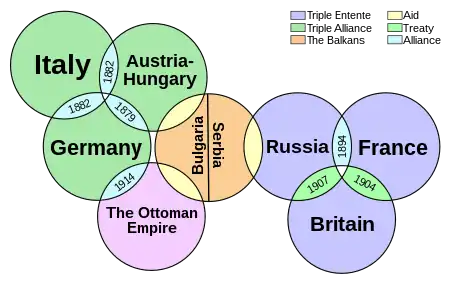

France played an important role in helping the Italian unification, especially in the defeat of the Austrian Empire, as well as in financial support. They were rivals for control of Tunisia and North Africa in the late 19th century. France won out, which led Italy to join the Triple Alliance in 1882 with Germany and Austria-Hungary. Tensions were high in the 1880s as expressed in a trade war. France needed allies against Germany, so it secretly negotiated a series of arrangements and treaties with Italy that by 1902 made sure that Italy would not support Germany in a war.

When World War I broke out in 1914, Italy was neutral at first but bargained for territorial aggrandizement. The best offer was made by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and France, which promised Italy large swaths of Austria and the Ottoman Empire. Both countries were among the "Big Four" of the Allies of World War I; however, Italian resentment at the difference between the promises of 1915 and the actual results of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles would be powerful factors in the rise to power of Benito Mussolini in 1922.

In the interwar period, France tried to be friendly with Mussolini to avoid his support of Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany. The efforts failed and when Germany defeated France in the Battle of France (1940), Italy also declared war, and was given control of an occupied zone near the common border. Corsica was added in 1942.

Both nations were among the Inner six that founded the European Community, the predecessor of the European Union. They are also founding members of the G7/G8 and NATO. Since April 9, 1956, Rome and Paris are exclusively and reciprocally twinned with each other, with the popular saying:

Country comparison

| Official name | French Republic | Italian Republic |

| Flag |  |

|

| Coat of Arms |  |

|

| Anthem | La Marseillaise | Il Canto degli Italiani |

| National day | 14 July | 2 June |

| Largest city | Paris – 13,064,617 (Metro)[3] | Rome – 4,342,212 (Metro) |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic | Unitary Parliamentary constitutional republic |

| Legislature | French Parliament | Italian Parliament |

| Head of State | Emmanuel Macron | Sergio Mattarella |

| Head of Government | Élisabeth Borne | Giorgia Meloni |

| Military | French Armed Forces | Italian Armed Forces |

| Official language | French | Italian |

| Main religions | 50% Christianity

42% No religion 4% Islam 4% Other |

84.4% Christianity, 11.6% No religion, 1.0% Islam, 3.0% Others[4] |

| Ethnic groups | 84% French, 7% other European, 10% North African, Other Sub-Saharan African, 4-7% Black, 5-10% Arab, 2% Asian, 1.2% Latin American and Pacific Islander.[5][6] | 91.3% Italians, 4,4% other Europeans, 1,9% Asians, 1,9% Africans, 0,5% Others[7] |

| Current Constitution | 4 October 1958 | 1 January 1948 |

| Area | 640,679 km2 (247,368 sq mi) | 301,340 km2 (116,350 sq mi) |

| EEZ | 11,691,000 km2 (4,514,000 sq mi) | 541,915 km2 (209,235 sq mi) |

| Time zones | 12 | 1 |

| Population | 67,918,000 (August 2022)[8] | 60,461,826 (2020)[9] |

| Population density | 118/km2 | 206/km2 |

| GDP (nominal) | $3.154 trillion[10] | $2.106 trillion[11] |

| GDP (nominal) per capita | $46,358[12] | $35,585 |

| GDP (PPP) | $3.231 trillion | $2.610 trillion |

| GDP (PPP) per capita | $49,492 | $43,376 |

| Expatriate populations | 220,000 French people in Italy (2021 data)[13] | 5,444,113 French citizens with Italian ancestry[14][15][16][17][18] 444,113 Italian citizens (2021)[19] |

| HDI | 0.901 | 0.892 |

| Currency | Euro and CFP franc | Euro |

History

Border

The two countries share a 488-kilometre (303 mi) border.[20] The border was largely determined in 1860 in the Treaty of Turin with minor rectifications performed during the 1947 Treaty of Paris. The kingdom of France had shared a border with the Duchy of Savoy since the incorporation of Provence into France under Charles VIII in 1486. The wider French-Italian border region had been part of the Kingdom of Burgundy-Arles during the 11th to 14th centuries.

The border between France and Savoy had remained in flux since the Italian Wars. In the early modern period, it was fixed in the Treaty of Turin of 1696. After the War of the Spanish Succession, the House of Savoy made large territorial gains, becoming the 18th-century nucleus for the later Italian unification. Savoy was occupied by revolutionary France from 1792 to 1815. Savoy, along with Piedmont and Nice, was conjoined into the Kingdom of Sardinia at the Congress of Vienna in 1815,[21] In 1860, under the terms of the Treaty of Turin, Savoie and Nice were annexed by France, while Lombardy passed to Italy. The last Duke of Savoy, Victor Emmanuel II, became King of Italy.

The border between the two countries does not match the linguistic border. Corsica, while traditionally Italian-speaking, is part of France, whereas the Valle d'Aosta, while traditionally French-speaking, is part of Italy.

There remains a territorial dispute over the ownership of the Mont Blanc summit, the highest mountain in Western Europe.

Impact of Emperor Napoleon I

Emperor Napoleon I ruled most of Italy (excluding Sicily and Sardinia), from 1796 to 1814. He introduced a number of major reforms that permanently altered the political and legal systems of the multiple small countries on the Italian peninsula, and helped inspire Italian nationalism and a demand for unification. The feudal laws were repealed, and the administration became a matter of expertise rather than corruption and patronage. The aristocracy lost its monopoly over the government, which opened up new opportunities to the middle class. Most church land was sold off. The Congress of Vienna (1814) reversed some of these provisions, but it failed to eliminate the revolutionary spirit introduced by Napoleon. Many secret societies were formed to transform and unify Italy; anticlericalism was an important new element, challenging the Pope's rule over central Italy, and the Catholic Church's major role throughout the peninsula. These ideas of liberty led to the "Risorgimento" which carried implications of unification, modernization and moral reform.[22]

Unification of Italy

France played a central role as Emperor Napoleon III sponsored the unification of Italy in the 1850s, and then blocked it by protecting the papal states in the 1860s.[23] Napoleon had long been an admirer of Italy and wanted to see it unified, although that might create a rival power. He plotted with Cavour of the Italian kingdom of Piedmont to expel Austria and set up an Italian confederation of four new states headed by the pope. Events in 1859 ran out of Napoleon's control in the Second Italian War of Independence. Austria was quickly defeated, but instead of four new states, a popular uprising and a new sense of Italian nationalism united all of Italy under Piedmont. The pope held onto Rome only because Napoleon sent troops to protect him. France's reward was the County of Nice (which included the city of Nice and the rugged Alpine territory to its north and east) and the Duchy of Savoy. Piedmont, known officially as the Kingdom of Sardinia, worked closely with France to unify Italy—militarily by pushing Austria out, and financially by providing over one billion gold francs in 1848–1860, which was half the money Sardinia needed. Cavour used the Rothschild Bank in Paris extensively, but also plated off against British and other European financiers.[24] He angered French and Italian Catholics when the pope lost most of his domains. Napoleon then reversed himself and angered both the anticlerical liberals in France and his erstwhile Italian allies when he protected the pope in Rome. When war with Prussia loomed in 1870, France withdrew its armies and the new Italian government absorbed the papal states and Rome.[25]

1870-1919

Relations after 1870 saw episodes of diplomatic and economic hostility, originating primarily in competition for control of North Africa. Germany's Chancellor Otto von Bismarck was worried by French revanchism—searching for revenge for the loss of Alsace Lorraine – so he sought to neutralize that by encouraging French expansion in Tunisia. Italy, a latecomer to imperialism also wanted Tunisia because many Italians lived there and especially because control of both Tunis and Sicily would make it a major Mediterranean power. France was closer and had many well-established business operations there. Italy was outmaneuvered, as Britain and Germany supported France. The French army invaded and took over Tunisia and Italians were furious. Franco-Italian relations were sharply negative through the 1880s. For example, there were disputes over tariffs and trade between the two countries plunged. Francesco Crispi a leading politician on the left, was indefatigable in stirring up hostility toward France.[26]

In a spirit of revenge against France, Italy formed a military alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1882, the Triple Alliance. The new Kaiser William II removed Bismarck from power in 1890, and engaged in reckless diplomatic adventurism in North Africa that disturbed Rome and Paris. Around this time, French and Italian relations became better after settling disputes. Italy's solution was to secretly move much closer to France, especially in the secret treaty of 1892, which effectively annulled the Italian membership in the Triple Alliance as far as ever making war against France. Tariff issues were resolved and in 1900, France supported Italy's ambitions to take over Tripolitania (modern Libya), and Italy recognized French predominance in Morocco. In 1902 both sides came to an understanding that regardless of the Italian renewal of membership in the Triple Alliance, Italy would not go to war with France. Meanwhile, the 1893 massacre of Italians at Aigues-Mortes had also strained the relationship.

All the dealings were secret, and Berlin and Vienna did not realize they had lost an ally.[27] As a consequence, when the First World War broke out in July 1914, Italy announced the Triple Alliance did not apply, declared itself neutral, and negotiated the best deal available. Britain and France thought Italian military manpower would be an advantage, and offered Italy large swaths of territory from Austria and the Ottoman Empire. Italy eagerly joined the Allies in early 1915.[28] Both countries were among the "Big Four". Italian forces were present and fought alongside their French allies in the Second Battle of the Marne and the subsequent Hundred Days Offensive on the Western Front, while French soldiers took part in the Battle of the Piave River and the Battle of Vittorio Veneto on the Italian front. Reactions in Italy were extremely negative due to the difference between the promises of 1915 and the actual results of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. Many Italians felt that the Entente had betrayed them. This intense dissatisfaction, mobilized veterans and led to the takeover of the Italian government by Fascists led by Benito Mussolini.[29][30]

1919-1945

In the 1920s there were several sources of friction, but they never escalated into a serious conflict. Italy demanded and received parity with the French Navy and terms of battleships at the Washington Conference in 1922. Tunisia continued to be a sore point due to its proximity to Italy large population of Italian settlers. France considered itself the protector of the independent state of Ethiopia, which Italy had long coveted. However, the Italian army was badly defeated at Adowa while trying to conquer Ethiopia in 1896; as a result, prior to 1935 had Italy focused on its colonies in Eritrea and Italian Somaliland. In European affairs, Mussolini proposed that four powers, Britain, France, Italy, and Germany cooperate to dominate European and more broadly, world affairs. France rejected the idea and the Four-Power Pact signed in July 1933 was vague and was never ratified by the four powers. However, after 1933, France tried to be friendly with Mussolini to avoid his support of Hitler's Nazi Germany.[31]

Ethiopia

When Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, the League of Nations condemned the action and imposed an oil boycott on Italy. British foreign minister Samuel Hoare and French Prime Minister Pierre Laval proposed a compromise satisfactory to Italy at the expense of Ethiopia, the Hoare–Laval Pact. They were both blasted at home for their appeasement of Italy. The catchphrase in Britain was, "No more Hoares to Paris!" and both lost their high posts.[32]

Italy's demands in 1938

In September 1938 in the Munich Agreement Britain and France used appeasement to meet Hitler's commands control of the German-speaking portion of Czechoslovakia. Italy supported Germany and now tried to obtain its own concessions from France. Mussolini demanded: a free port at Djibouti, control of the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railroad, Italian participation in the management of Suez Canal Company, some form of French-Italian condominium over Tunisia, and the preservation of Italian culture in French-held Corsica with no French assimilation of the people.[33] Italy opposed the Anglo-French monopoly over the Suez Canal which meant that all Italian merchant traffic to its colony of Italian East Africa was forced to pay tolls to the Suez Canal Company to transit through the canal. France outright rejected all of Mussolini's demands. Paris suspected that Italy's true intentions were the territorial acquisition of Nice, Corsica, Tunisia, and Djibouti. France also launched threatening naval maneuvers as a warning to Italy. As tensions between Italy and France escalated, Hitler made a major speech on 30 January 1939 in which he promised German military support in the case of an unprovoked war against Italy.[34]

World War II

When Germany was on the verge of victory over France in 1940, Italy also declared war and invaded southern France. Italy obtained control of an occupation zone near the common border.[35] Corsica was added in 1942. The Vichy regime that controlled southern France was friendly toward Italy, seeking concessions of the sort Germany would never make in its occupation zone.[36]

1945-2008

Both nations were among the Inner six that founded the European Community, the predecessor of the EU. They are also founding members of the G7/G8 and NATO. With a powerful Communist Party in Parliament, and a strong presence of neutral elements among the people, Italy was at first hesitant to join NATO. At first, much like Britain, France was opposed to Italian membership. However, French leadership realized soon enough that the security of their country depended on a non-hostile Mediterranean region, leading to overall support of Italy joining. Wanting closer ties to the United States, Italy did eventually join NATO, but avoided deep involvement in military planning.[37][38]

In the 1960s, France's Charles de Gaulle, developed a foreign policy that would minimize the role of Britain and the United States, while trying to build up an independent European base. While not formally abandoning NATO, de Gaulle pulled France out of its main activities. Italy generally was reluctant to follow France, and insisted on the importance of the strong European Union that included Britain.[39][40]

Since 2018

Historically strong relations between France and Italy significantly deteriorated following the formation of a government coalition in Italy comprising the Five Star Movement and the League in June 2018. Points of contention between the countries included immigration, budgetary constraints, the Second Libyan Civil War, the CFA Franc, and Italian support for opposition movements in France.

In June 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron accused Italy of "cynicism and irresponsibility" for turning away the Aquarius Dignitus migrant rescue ship. The Italian government summoned the French ambassador in response, with Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte describing Macron's remarks as "hypocritical".[41]

In September 2018, Italian Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini condemned France's foreign policy in Libya, including its advocacy for the 2011 military intervention in Libya and actions during the Second Libyan Civil War, accusing France of "putting at risk the security of North Africa and, as a result, of Europe as a whole" for "economic motives and selfish national interest".[42]

On 9 October 2018, French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe accused Salvini of "posturing" on immigration and urged Italy to coordinate with other European countries prior to a meeting between the two men. Immediately following the meeting, Salvini praised the leader of the French opposition National Rally party, noting that he feels "closer to the views of Marine Le Pen".[43]

On 21 October 2018, Salvini accused France of "dumping migrants" on Italian soil.[44]

On 7 January 2019, both Italian Deputy Prime Ministers, Salvini and Luigi Di Maio, announced their support for the yellow vests movement in France, which has been involved in widespread protests against the French government.[45]

In January 2019, Di Maio accused France of causing the migrant crisis by having "never stopped colonising Africa" through the CFA Franc.[46] France responded by summoning the Italian ambassador.[47] Salvini subsequently backed Di Maio by accusing France of being among people who "steal wealth" from Africa, and added that France had "no interest in stabilising the situation" in Libya due to its oil interests.[48]

On 5 February 2019, Di Maio met with leaders of the French yellow vests movement, saying "The wind of change has crossed the Alps,".[49]

On 7 February 2019, France recalled its ambassador from Rome in order to protest Italian criticism of French policies, which it described as "repeated accusations, unfounded attacks and outrageous declarations" that were "unprecedented since the end of the war".[50]

Following the 2019 Italian government crisis, which led to the collapse of the alliance between the League and Five Star Movement, a second Cabinet was formed under Giuseppe Conte, composed largely of the Five Star Movement and the centre-left Democratic Party. As a result of this change, relations between France and Italy improved markedly, and France voiced support for Italy's struggle against the COVID-19 outbreak in the country.[51] In an interview with the French newspaper Le Monde on 27 February 2020, Foreign Minister Luigi Di Maio praised Macron's trip to Naples during the outbreak as a show of European solidarity.[52] On that same day, during the first Franco-Italian summit since the cooling of relations in 2018, Premier Giuseppe Conte further remarked that France is Italy's historic ally and that ties between the two countries can never be damaged in the long-term due to occasional disagreements.[53]

On 26 November 2021, the Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi signed with Emmanuel Macron the Quirinal Treaty at the Quirinal Palace, Rome. The Treaty, consisting of 13 articles, "will promote the convergence of French and Italian positions, as well as the coordination of the two countries in matters of European and foreign policy, security and defence, migration policy, economy, education, research, culture and cross-border cooperation".[54] According to both governments, the Treaty is the beginning of a new convergence between the two nations in the leadership and the advance of the European Union.

Following the election of Giorgia Meloni as Prime Minister in the 2022 Italian general election, relations once again deteriorated over disagreements on immigration.[55]

Economy

France is Italy's second-largest trading partner and, symmetrically, Italy is also the second-largest trading partner of France.[56]

Intercultural influences

Italian culture in France

Since the days of Ancient Rome, together with Ancient Greece considered to be the birthplaces of Western civilization, Italian culture left a powerful mark on Europe and the West throughout the centuries, in every aspect. A notable and more recent example, the Renaissance had great political, ideological, social and architectural influence on France during the 16th century, and is regarded as a precursor to the Age of Enlightenment and the French Revolution.

Many cultural landmarks in Paris, such as the Arc de Triomphe, Panthéon, Palais du Luxembourg, Jardin du Luxembourg, Les Invalides and the Château de Versailles were heavily influenced by Italian architecture and Roman landmarks.

The Palace of Fontainebleau is considered the main treasure chest of the Italian Renaissance in France. Benvenuto Cellini and Leonardo da Vinci were active at Francis I's court and brought with them Italian models for the emergent French Renaissance.

The House of Bonaparte, ruler of the First French Empire under Napoleon Bonaparte, traces its roots back to Italy, precisely in San Miniato, located in the region of Tuscany.

Two queens of France, Caterina de Medici and Maria de Medici, and a chief minister of France, Giulio Mazzarino, were Italians.

Many Italian artists of the 19th and 20th centuries (Giuseppe De Nittis, Boldini, Gino Severini, Amedeo Modigliani, Giorgio de Chirico) went to France to work, at a time when Paris was the international capital of arts.

Many Italians immigrated to France during the first part of the 20th century: in 1911, 36% of foreigners living in France were Italian.[57] Immigrants have sometimes suffered a violent anti-Italianism like the Vêpres marseillaises (Marseilles vespers) in June 1881 or Aigues-Mortes massacre on 17 August 1893.[58] Today, it is estimated that as many as 5 million French nationals have Italian ancestry going back three generations.[59]

Nowadays 414,000 Italian nationals live in France, while 220,000 French citizens live in Italy.[60]

French culture in Italy

The Norman and the Angevin dynasties that ruled the Kingdom of Sicily and the Kingdom of Naples during the Middle Ages came from France. The Normans introduced a distinct romanesque art and castle architecture imported from Northern France. At the end of the 13th century, the Angevin introduced gothic art in Naples, giving birth to a peculiar gothic architectural style inspired by Southern French gothic.

Provençal writers and troubadours of the 12th and 13th centuries had an important influence on the Dolce Stil Novo movement and on Dante Alighieri.

The Aosta Valley region in northwest Italy is culturally French and the French language is recognised as an official language there.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, many French artists lived and worked in Italy, especially in Rome, which was the international capital of arts. These include Simon Vouet, Valentin de Boulogne, Nicolas Poussin, Claude Lorrain and Pierre Subleyras.

The Villa Medici in Rome hosts the French Academy in Rome. The academy was founded in 1666 by Louis XIV to train French artists (painters, sculptors, architects) and make them familiar with Roman and Italian Renaissance art. Today the academy is responsible for promoting French culture in Italy.

From 1734 to 1861, the Kingdom of Naples and of Sicily were under the domination of the Spanish branch of the Bourbon dynasty, originating from France. Charles III, king of Naples was the grand son of Louis, Dauphin de France, son of Louis XIV.

During the Napoleonic era, many parts of Italy were under French control and were part of the First French Empire. The Kingdom of Naples was ruled by Joseph Bonaparte, brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, and then by Marshall Joachim Murat : it was under Joseph Bonaparte's rule that feudalism was abolished, in 1806.

The Savoy dynasty who ruled on Piedmont and Sardinia and led the unification of Italy in 1861 is of French descent, coming from the French-speaking region of Savoie, in the western Alps.

Institutions

Both France and Italy are founder members of the European Union and adopted the euro from its introduction.

Since 1982, an annual summit has formalised French-Italian cooperation. The first was held in Villa Madama.[61]

Military

The Prime minister of the Kingdom of Sardinia Camillo Benso was able to take Napoleon III on his side after the Orsini affair during the Italian Unification: The French army was allied with Victor Emmanuel II of Italy during the Second Italian War of Independence and defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Magenta and the Battle of Solferino. After that, France opposed Italy during the Capture of Rome (but did not do anything to prevent it), which represented the end of the Papal temporal power.

After World War I the governments of the two countries were both among the big four that defeated the Central Powers.

The last military conflict was the Second Battle of the Alps in April 1945.

Sport

- France-Italy football rivalry is one of the most famous sports rivalries worldwide.

- The Giuseppe Garibaldi Trophy is a trophy for the winner of the Six Nations match between France and Italy in rugby union.

Resident diplomatic missions

- France has an embassy in Rome and consulates-general in Milan and Naples.[62]

- Italy has an embassy in Paris and consulates-general in Lyon, Marseille, Metz and Nice.[63]

Embassy of France in Rome

Embassy of France in Rome Embassy of Italy in Paris

Embassy of Italy in Paris Consulate-General of Italy in Paris

Consulate-General of Italy in Paris Consulate-General of Italy in Lyon

Consulate-General of Italy in Lyon

See also

- Foreign relations of France

- Foreign relations of Italy

- Hôtel de Boisgelin : Italian embassy in France

- Palazzo Farnese : French embassy in Italy

- France–Italy border

Notes and references

- ↑ "Twinning with Rome". Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ↑ "Les pactes d'amitié et de coopération". Mairie de Paris. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- ↑ Comparateur de territoire: Aire d'attraction des villes 2020 de Paris (001), 2018 population, INSEE

- ↑ "Special Eurobarometer 516". European Union: European Commission. September 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021 – via European Data Portal (see Volume C: Country/socio-demographics: IT: Question D90.2.).

- ↑ Yazid Sabeg et Laurence Méhaignerie, Les oubliés de l'égalité des chances, Institut Montaigne, January 2004

- ↑ Crumley, Bruce (24 March 2009), "Should France Count Its Minority Population?", Time, retrieved 11 October 2014

- ↑ "Tuttitalia".

- ↑ "Demography - Population at the beginning of the month - France (including Mayotte since 2014)Identifier 001641607". www.insee.fr. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ↑ "Italy Population (2022) - Worldometer". www.worldometers.info. Retrieved 2022-09-17.

- ↑ "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2021". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ↑ "GDP (current US$) - Italy | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2022-09-17.

- ↑ "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2021". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ↑ Recchi, Ettore; Baglioni, Lorenzo Gabrielli e Lorenzo G. (2021-04-16). "Italiani d'Europa: Quanti sono, dove sono? Una nuova stima sulla base dei profili di Facebook". Neodemos (in Italian). Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- ↑ Documento "Italiens" del CIRCE dell'Università Sorbona - Parigi 3

- ↑ "Italiani nel Mondo: diaspora italiana in cifre" [Italians in the World: Italian diaspora in figures] (PDF) (in Italian). Migranti Torino. 30 April 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ↑ "Rapporto Italiano Nel Mondo 2019 : Diaspora italiana in cifre" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-01-01.

- ↑ "Italiani Nel Mondo : Diaspora italiana in cifre" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- ↑ Cohen, Robin (1995). Cambridge Survey. Cambridge University Press. p. 143. ISBN 9780521444057. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

5 million italians in france.

- ↑ "Rapporto Italiano Nel Mondo 2021 : Diaspora italiana in cifre" (PDF). Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- ↑ "CIA - The World Factbook -- Field Listing - Land boundaries". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 2007-06-13.

- ↑ Wells, H. G., Raymond Postgate, and G. P. Wells. The Outline of History, Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1956. p. 723–753.

- ↑ Martin Collier, Italian Unification 1820-71 ( Heinemann, 2003) pp 1-31.

- ↑ William E. Echard, "Louis Napoleon and the French Decision to Intervene at Rome in 1849: A New Appraisal." Canadian Journal of History 9.3 (1974): 263-274. excerpt

- ↑ Rondo E. Cameron, "French Finance and Italian Unity: The Cavourian Decade." American Historical Review 62.3 (1957): 552-569. online

- ↑ Harry Hearder, Cavour (1994) 99-159.

- ↑ Mark I. Choate, "'The Tunisia Paradox': Italy's Strategic Aims, French Imperial Rule, and Migration in the Mediterranean Basin." California Italian Studies 1, (2010): 1-20." (2010). online

- ↑ Christopher Andrew, Théophile Delcassé and the Making of the Entente Cordiale: A Reappraisal of French Foreign Policy 1898–1905 (1968) pp 20, 82, 144, 190.

- ↑ William A. Renzi, "Italy's neutrality and entrance into the Great War: a re-examination." American Historical Review 73.5 (1968): 1414-1432. online

- ↑ Margaret MacMillan (2007). Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World. Random House Publishing. pp. 428–30. ISBN 9780307432964.

- ↑ Giovanna Procacci, "Italy: From Interventionism to Fascism, 1917-1919." Journal of contemporary history 3.4 (1968): 153-176. online

- ↑ Jacques Néré, The foreign policy of France from 1914 to 1945 (2002) pp 132-154.

- ↑ Andrew Holt, "'No more Hoares to Paris': British foreign policymaking and the Abyssinian Crisis, 1935." Review of International Studies 37.3 (2011): 1383-1401.

- ↑ H. James Burgwyn, Italian Foreign Policy in the Interwar Period, 1918-1940 (1997). pp 182-183.

- ↑ Burgwyn, Italian Foreign Policy in the Interwar Period, 1918-1940 pp 194-185.

- ↑ Emanuele Sica, Mussolini's Army In the French Riviera, the Italian occupation of France (2016)

- ↑ Karine Varley, "Vichy and the Complexities of Collaborating with Fascist Italy: French Policy and Perceptions between June 1940 and March 1942." Modern & Contemporary France 21.3 (2013): 317-333.

- ↑ E.Timothy Smith, The United States, Italy and NATO, 1947-52 (2015) pp 56-61, 67-72; excerpts.

- ↑ Alessandro Brogi, A Question of Self-Esteem: The United States and the Cold War Choices in France and Italy, 1944-1958 (2002) online Archived 2019-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ W.W. Kulski, De Gaulle and the world: the foreign policy of the fifth French Republic (1966) pp 145, 166, 257.

- ↑ Luca Ratti, Italy and NATO expansion to the Balkans: An examination of realist theoretical frameworks (2004). pp 66-67.

- ↑ Giuffrida, Angela; Jones, Sam (13 June 2018). "Italy summons French ambassador in row over migrant rescue boat". The Guardian. in Madrid agencies. Retrieved 8 February 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ↑ "As clashes rage in Libya's Tripoli, Italy takes swipe at France". France 24. 4 September 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ "France tells Italy to stop 'posturing' on immigration and find a solution". www.thelocal.fr. 9 October 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ "Border tensions boil over as France 'dumps' migrants in Italy". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ "Italian leaders back French 'yellow vest' protesters". www.thelocal.it. 7 January 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ "France angered by Italy's Africa remarks". BBC News. 22 January 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ "France summons Italian envoy over Di Maio Africa comments". www.euractiv.com. 22 January 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ Johnson, Miles (22 January 2019). "Matteo Salvini accuses France of 'stealing' Africa's wealth". Financial Times. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ "Italy's deputy PM meets 'yellow vest' protestors in France". www.thelocal.it. 5 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ Davies, Pascale (2019-02-07). "France-Italy row: Tajani hits out at Di Maio after Paris complains over 'Rome attacks'". euronews. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

- ↑ "French President Macron expresses solidarity with Italy, says Europe must not be selfish". france 24. 2020-03-28. Retrieved 2020-03-28.

- ↑ "Di Maio interview with Le Monde newspaper". ministero degli esteri (in Italian). 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2020-03-28.

- ↑ "Summit between Italy and France in Naples". napoli today (in Italian). 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2020-03-28.

- ↑ "Will a new French-Italian pact reshape Europe post-Merkel?". 26 November 2021.

- ↑ "Meloni and Macron clash over migrants". 11 November 2022.

- ↑ "Economic relations - France-Diplomatie - Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Development". Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- ↑ Corti, Paola (2003), L'emigrazione italiana in Francia: un fenomeno di lunga durata Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Altreitalie, no. 26, janvier-juin 2003

- ↑ "L'immigration italienne en Provence au XIXe siècle". 24 December 2006. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ Cohen, Robin (1995). Cambridge Survey. Cambridge University Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-521-44405-7. Retrieved 2009-05-11 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Recchi, Ettore; Baglioni, Lorenzo Gabrielli e Lorenzo G. (2021-04-16). "Italiani d'Europa: Quanti sono, dove sono? Una nuova stima sulla base dei profili di Facebook". Neodemos (in Italian). Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- ↑ "France-Diplomatie - Political relations". www.diplomatie.gouv.fr. Archived from the original on 2012-03-13.

- ↑ "La France en Italie". it.ambafrance.org. Retrieved 2021-12-31.

- ↑ "Ambasciata d'Italia - Parigi". ambparigi.esteri.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2021-12-31.

Further reading

- Cameron, Rondo E. "French Finance and Italian Unity: The Cavourian Decade." American Historical Review 62.3 (1957): 552–569. online

- Choate, Mark I. "Identity politics and political perception in the European settlement of Tunisia: the French colony versus the Italian colony." French Colonial History 8.1 (2007): 97–109. online

- Choate, Mark I. "Tunisia, Contested: Italian Nationalism, French Imperial Rule, and Migration in the Mediterranean Basin." California Italian Studies 1.1 (2010). online

- Echard, William E. , "Louis Napoleon and the French Decision to Intervene at Rome in 1849: A New Appraisal." Canadian Journal of History 9.3 (1974): 263–274. excerpt

- Langer, William L. The Diplomacy of Imperialism, 1890-1902 (1951)

- Pearce, Robert, and Andrina Stiles. Access to History: The Unification of Italy 1789-1896 (4th ed., Hodder Education, 2015) Undergraduate textbook.

- Ward, Patrick J. Relations Between France and Italy. (1934) 50pp online

External links

- "France and Italy", The French Foreign Ministry