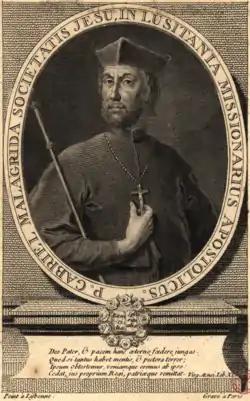

Gabriel Malagrida (18 September or 6 December 1689 – 21 September 1761) was an Italian Jesuit missionary in the Portuguese colony of Brazil and influential figure in the political life of the Lisbon Royal Court who described the devastating 1755 Lisbon earthquake as retribution prompted by God's wrath.

Malagrida was famously caught up in the Távora affair. When he could not be convicted for high treason, the Portuguese Prime Minister Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, Marquis of Pombal, whose brother served as the head Inquisitor, had him executed for heresy.

Biography

Early life in the Jesuit Order and missionary work

Gabriel Malagrida was born in 1689 in Menaggio, Italy, the son of Giacomo Malagrida, a doctor, and wife Angela Rusca. He entered the Jesuit order at Genoa in 1711. In 1721 he set out from Lisbon and arrived on the Island of Maranhão towards the end of that year. From there he proceeded to Brazil, where he worked as a missionary for 28 years, and developed a reputation for both holiness and powerful preaching.[1] In 1749 he was sent to Lisbon, where he was received with honour by King João V of Portugal. In 1751 he returned to Brazil, but was recalled to Lisbon in 1753 upon the request of Marianna of Austria, the queen dowager and mother of King José I of Portugal, who had succeeded to the throne upon the death of his father.[2]

Malagrida's influence at the Court of Lisbon met with deep hostility from the prime minister, Carvalho, the future Marquis of Pombal. Carvalho was attempting to rebuild Lisbon following the 1755 earthquake, which Malagrida preached was the punishment of a just God on a sinful people. Carvalho resented the implicit criticism of the government, and persuaded King José to banish Malagrida to Setúbal in November 1756 and had all Jesuits removed from the Court.[2]

The Távora affair

When King José I and his valet Pedro Teixeira were returning to Belém from the Palace of the Marquês and Marquesa of Távora in September 1758, three masked horsemen stopped the carriage in the dead of night, and fired a musket-shot that wounded the king in the arm and shoulder. The attempt on the king's life gave Carvalho a pretext to crush the independence of the nobility. He magnified an act of private vengeance on the part of a jealous husband into a widespread conspiracy.[3] Carvalho's spies identified two of the horsemen, and they were arrested and tortured. Their confessions implicated the Marquis and Marquise of Távora. By December he had uncovered what he believed to be a plot to assassinate the King and replace him with the Duke of Aveiro. Malagrida, who had returned from exile, was arrested and tried for his alleged involvement in the plot.

Gabriel Malagrida was declared guilty of high treason, but, as a priest, could not be executed without the consent of the Inquisition. He was imprisoned in the dungeon beneath Belém Tower with other Jesuits who were also implicated. When the Inquisition could find no proof of guilt, Carvalho had his own brother replace the head inquisitor. Under the harsh conditions of his two-and-a-half years imprisonment, Malagrida went mad.[4] He was found guilty of heresy based upon two transcripts of visions it was claimed he experienced. The first was on the Anti-Christ, and the second was entitled The Heroic And Wonderful Life of the Glorious Saint Anne, Mother of the Virgin Mary, Dictated By This Saint, Assisted By And with the Approbation And Help of This Most August Sovereign, And Her Most Holy Son.[5] His authorship of these treatises has never been proved.[2]

Finding the works attributed to Malagrida as heretical, he was sentenced to death. On 21 September 1761, he was strangled at the garrotte in Rossio Square. His corpse was then burned on a bonfire and the ashes were thrown into the Tagus river.[1]

A monument in his honour was erected in 1887 in the parochial church of Menaggio.[2]

Cultural trace

Stendhal (1783–1842) mistakenly ascribed to Malagrida the maxim "Words have been given to men in order to hide their thoughts" (The Red and the Black, Part 1, XXII, epigraph), which go back to a remark by a capon made in a fable/dialogue written by Voltaire in 1763,[6] often mistakenly attributed to Talleyrand.

Notes

- 1 2 Mostefai, Ourida; Scott, John T. (2009). Rousseau and "L'Infame": Religion, Toleration, and Fanaticism in the Age of Enlightenment. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-2505-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Ott, Michael. "Gabriel Malagrida." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 9 Mar. 2015

- ↑ Prestage, Edgar. "Marquis de Pombal." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 9 Mar. 2015

- ↑ "Gabriel Malagrida", Jesuit Restoration 1814

- ↑ Shrady, Nicholas. The Last Day: Wrath, Ruin, and Reason in the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755. p. 178.

- ↑ Dialogue between a capon and a fattened hen

References

- Mury, Histoire de Gabriel Malagrida (Paris, 1884; 2nd ed., Strasburg, 1899; Ger. trans., Salzburg, 1890);

- Un monumento al P. Malagrida in La Civilità Cattolica, IX, series XIII (Rome, 1888), 30–43, 414–30, 658–79;

- Juizo da verdadeira do terremoto, que padeceo a corte de Lisboa (1756).