| Microlophus albemarlensis | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Female, Santa Fe Island | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Male, Isabela Island | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Iguania |

| Family: | Tropiduridae |

| Genus: | Microlophus |

| Species: | M. albemarlensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Microlophus albemarlensis (Baur, 1890) | |

| |

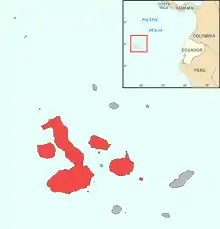

| Range (red) in the Galápagos Islands | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Microlophus albemarlensis, the Galápagos Lava lizard, also known as the Albemarle Lava lizard, is a species of Lava lizard. It is endemic to the Galápagos Islands, where it occurs on several islands in the western archipelago: the large islands Isabela, Santa Cruz, Fernandina, Santiago and Santa Fe, as well as several smaller islands: Seymour, Baltra, Plaza Sur, Daphne Major and Rábida.[2] It is the most widespread of the Galápagos species of Microlophus, the others only occurring on single islands.[3] Some authors however, consider populations on Santiago, Santa Cruz, and Santa Fe (and associated small islands) to be distinct species (M. jacobi, M. indefatigabilis and M. barringtonensis, respectively).[4] The species is commonly attributed to the genus Microlophus but has been historically placed in the genus Tropidurus.

Description

Galapagos lava lizards are generally small, ranging from 4-7 inches long. Males are around 6-7 inches long, while females range from 4-7 inches. However, they have been known to grow up to as long as a foot in length. Their tail is often as long or longer than their actual body. Their bodies are characterized by the slimness, pointed heads, and long tails. Their colors range depending on sex; males are generally more brightly colored, with yellow and gold stripes, while females can be recognized by a red marking on their throat and head. Habitat has an enormous impact on appearance of the Galapagos lava lizard. Lava lizards have regenerative tails, which is useful as one of their protection mechanisms because they are capable of dropping their tails; However, they rarely grow back to their original length, but this mechanism does allow them to escape predation.[4]

Classification

The Galapagos lava lizard is also known as the Albemarle lava lizard. There are seven species within the Galapagos lava lizard population and these species are found on several islands. Its Latin name is Microlophus albemarlensis, most generally, however, Microlophus indefatigabilis is a more specific classification based on the specific island location. This is the most widespread species of the genus Microlophus and is related to the genus Tropidurus. More broadly speaking, the Galapagos lava lizard is considered an iguana and classified as a reptile. The population of M. albemarlensis is found only within the Galapagos Islands (note: there are several smaller islands that make up the Galapagos Islands).[5]

George Baur first described the Galápagos lava lizard in 1890. He named it Tropidurus albemarlensis, after an alternate name of the Isabela Island, Albemarle. He also described T. indefatgiabilis from Santa Cruz Island (also known as Indefatigable Island). Darrel Frost, in 1992, classifgied all species of Tropidurus into Microlophus, based on a number of characteristics. The defining, most notable characteristic that contributed to this classification was the discs on the tips of the male reproductive organs. Some populations of M. albemarlensis are regarded as different species based on genetic differences and location differences, though no unique morphological differences have been noted. The lava lizards are within Tropiduridae, a family of South American lizards.[1]

Habitat

The Galapagos lava lizard inhabits the Galapagos islands and is a prime example of Darwin’s natural selection. The Galapagos Islands are a chain of islands in the Eastern Pacific, formed of lava piled and scattered volcanoes. They are located on both sides of the equator, making the Galapagos lava lizard a bi-hemisphere inhabitant. The climate on these islands is tropical and semi-arid, providing ideal conditions for these lizards to thrive. Each island is home to a certain variant of lizard. Their habitat must have sun shelter and dry leaves as well as rocks, so they can sunbathe and hide (two typical behaviors of the lava lizard). This implies a dry, lowland area where soil is loose and dry leaf litter is common so that they can bury and stay cool at night. They also must have enough food resources around their home, such as contain plants, seeds, arthropods, and flowers.[6]

Conservation

Natural predators of these lizards include, but are not limited to, snakes, scorpions, themselves (cannibalism), hawks, and herons. The major defense mechanism used by these lizards involves dropping their tail; their tail continues to move and thus distracts their predators while the actual lizard will camouflage or flee. In terms of conservation status, it is clear they are not under immediate threat; however, global warming and human habitat destruction have the chance to change this.[5] Humans should be mindful of their pets if they live in a habitat that is home to lava lizards and also be wary of human-induced destruction to the earth. A study focused on how vehicle collisions with wildlife impacts the Lava lizard population, as Lava lizards tend to live in areas where there could be roads running through their habitat. This study intended to aid conservation efforts as there are planned increases in road networks in areas where the lava lizard is most abundant. It was found that as one moves away from the road, around 100 m away, there is an increase in lizard population by 30%. Roadkill lizards were also studied, and it was found that 71% of lizards suffered tail loss from vehicles. This statistic emphasizes the need to reconsider the effects of modernization of nature as it could negatively impact several species.[7]

Moreover, climate change is a significant threat to the Galapagos lava lizard population. People are encouraged to educate themselves regarding the impacts of human actions of environmental status in various locations as these impacts widely differ depending on continent, hemisphere, etc.

Diet

Galápagos lava lizards feed on insects, spiders, and other arthropods, with maggots (fly larvae), ants, and beetles being most common prey items. Around human settlements they will also consume bread crumbs, meat scraps and other litter.[8] Fragments of leaves and flowers, as well as large seeds, have been found in the stomachs, and lizards have been observed in trees consuming freshly sprouted leaves as high as 2 m (7 ft) off the ground.[9]

The Galapagos lava lizard is classified as an omnivore; however, they mostly indulge in ants, spiders, months, flies, and other similar arthropods.[10] Thus, their presence is helpful in controlling insect populations and they play a vital role in the Galapagos food chain. While most of these insects are caught from a stationary position, utilizing the sit and wait method, some lizards go digging for subsurface neuropteran and beetle larvae. This digging occurs as they use their head and forelegs to move soil.[5] If found around human settlements, they feed on crumbs and scraps from human food. Lava lizards are also thought to eat one another as well as plants and seeds during dry spells (ex: flowers). Galapagos lava lizard diet has been found to vary with body size; this correlation is not seen among prey body size, but rather the lizard itself. The amount of plant items in the stomachs of these lizards strongly correlates to body size and percent herbivory. No correlation was found between animal feed and body size. This correlation is observed as size effects efficiency of energy consumption. Body size does not correlate with presence of absence of predators.[11]

A commensal relationship exists when the lava lizard is perched on the tails of marine iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) in order to eat insects attracted to these iguanas.[5]

Behavior

Reproduction

Male Galapagos lava lizards often mate with any female that is in proximity to his territory. A male’s territory can range up to 400 square meters;[5] in order to distinguish itself and fend off competitors, the male executes a performance classified as ‘push ups’. This performance intimidates opponents and boost the males appearance in terms of size and strength. If, on the off chance, another male feels big and strong enough, the two will compete in a push up contest. This contest does not end until there is one winner. Sometimes this means biting and tail slaps can occur if the duel occurs for too long.[5]

Once a male wins this competition, he can mate with a female. Breeding season typically occurs in the warm season,[5] from November to March. Females lay around four small eggs is their burrow. The eggs incubate for around 3 months and then hatch. Infants are typically three to four centimeters. The average number of offspring is around 2 as it ranges from 1-4 inches long,[5] making them extremely vulnerable to predators such as birds. It is essential to note the difference in maturing processes between females and males. Females reach sexual maturity as early as nine months while males mature after three years.[12]

Before maturity, males and females are hard to distinguish. Since females mature faster, once the female has matured, it is much easier to distinguish between sexes.[13]

Activity and aggression

Galápagos lava lizards are active during the day, emerging around sunrise, withdrawing during the heat of midday, and resuming activity in the afternoon. At night they burrow under soil or leaf-litter, fully submerged, often returning to the same resting area each night.[8]

Galapagos lava lizards are known for being extremely territorial and aggressive in terms of intraspecies interaction. Often times, they exhibit push up actions in public areas to threaten and scare away any intruders. Head movements described as ‘bobbing’ also dissuade males from fighting or entering the territory. If all else fails, the lizard will resort to biting competitors and slapping tails.[5] Any attempt to make oneself look big and strong is welcomed by the lizard. The lava lizard also has the ability to change color to make it camouflage more with its environment; its color also has the ability to change based on temperature changes or even mood changes. Color varies with location and habitat. Lava lizards can live up to 10 years, which is a long life for a reptile. Galapagos lava lizards appear when the sun rises and increase their activity throughout the day.[12] Depending on temperature, they retreat when the temperature becomes the most unbearable, normally during the mid-afternoon; they seek shelter and shade for the rest of the day and sleep in cool places at night. They do not communicate with one another vocally, rather they communicate through visual display. There is potential for lava lizards to play a role as pollinators across the islands they inhabit, however, this behavior is only observed in 8.4% of the population and further studies must be done. Despite this low percentage, this behavior was observed in many of the subspecies of Galapagos lava lizards.[14]

Evolution of behavior

Conspecific communication signals in males have had important implications for the evolution of these lizards. Conspecific display recognition costs are relaxed in species that have evolved alone in isolation (ex: on an island). Conspecific display recognition was lost early in evolution, however, for this species due to allopatric speciation. It reemerged later when selection favored discrimination of male displays.

Interaction with humans

Lava lizards are present year-round, and they stay active during most of the day. They are cold blooded omnivores who mostly prefer to eat plants and insects;[5] they do not interact with humans other than occasionally utilizing their food scraps as a food resource. Thus, the Lava lizard is not a threat to humans. Their bite is not dangerous; however, they have not been heard of biting a human. Their aggression is mostly towards one another in the form of competition over territory and mating. Lava lizards can be kept as pets and are often useful in the study of evolution as it is believed that the 7 species of lava lizard descended from a single common ancestor. As pets, they are not in danger as they are fed their typical diet and kept in temperate conditions, which is essential as they are cold blooded organisms.[12]

See also

References

- 1 2 Márquez, C.; Yánez-Muñoz, M.; Cisneros-Heredia, D.F. (2016). "Microlophus albemarlensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T177934A1499883. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T177934A1499883.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- 1 2 Microlophus albemarlensis at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 21 January 2021.

- ↑ Andy Swash; Rob Still & Ian Lewington (2005). Birds, Mammals, and Reptiles of the Galápagos Islands: An Identification Guide. Yale University Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-0-300-11532-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Chow, Tze Keong (2004). "Galapagos Lava Lizard". University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ↑ Jackson, M. H. 1985. Galapapagos: A Natural History Guide. The University of Calgary Press

- ↑ Dawn Tanner, Jim Perry, Road effects on abundance and fitness of Galápagos lava lizards (Microlophus albemarlensis), Journal of Environmental Management, Volume 85, Issue 2, 2007, Pages 270-278,

- 1 2 Stebbins, Robert C.; Lowenstein, Jerold M. & Cohen, Nathan W. (1967). "A field study of the lava lizard (Tropidurus albemarlensis) in the Galapagos Islands". Ecology. 48 (5): 839–851. doi:10.2307/1933742. JSTOR 1933742.

- ↑ Van Denburgh, J. & J. R. Slevin (1913). "Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galapagos Islands, 1905–1906. IX. The Galapagoan lizards of the genus Tropidurus with notes on iguanas of the genera Conolophus and Amblyrhynchus". Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. Series 4. 2: 132–202.

- ↑ Metcalfe, Todd (2010). "Lava Lizard". geol.umd.edu. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ↑ Schluter, Dolph. “Body Size, Prey Size and Herbivory in the Galápagos Lava Lizard, Tropidurus.” Oikos, vol. 43, no. 3, [Nordic Society Oikos, Wiley], 1984, pp. 291–300, doi:10.2307/3544146.

- 1 2 3 "Animal Corner". 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Prieto, A., J. Leon, O. Lara. 1976. Reproduction in the tropical lizard, Tropidurus hispidus. Herpetologica, 32/3: 319.

- ↑ HERVÍAS-PAREJO, S., NOGALES, M., GUZMÁN, B., TRIGO, M.d.M., OLESEN, J.M., VARGAS, P., HELENO, R. and TRAVESET, A. (2020), Potential role of lava lizards as pollinators across the Galápagos Islands. Integrative Zoology, 15: 144-148. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12386