Andrey Andreyevich Vlasov | |

|---|---|

Андрéй Андрéевич Влáсов | |

Vlasov in 1942 | |

| Chairman of the Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia | |

| In office 14 November 1944 – May 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Meandrov[1] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 14, 1901 Lomakino, Nizhny Novgorod Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | August 1, 1946 (aged 44) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1930–1942) |

| Awards |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | (1919–1922) (1922–1942) (1942–1944) (1944–1945) |

| Years of service | 1919–1945 |

| Rank | Lieutenant general |

| Commands | |

| Battles/wars | |

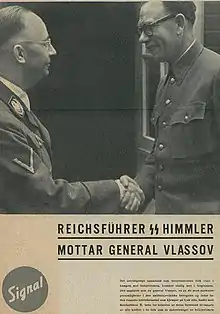

Andrey Andreyevich Vlasov (Russian: Андрей Андреевич Власов, September 14 [O.S. September 1] 1901 – August 1, 1946) was a Soviet Red Army general and collaborator with Germany. During the Axis-Soviet campaigns of World War II he fought (1941–1942) against the Wehrmacht in the Battle of Moscow and later was captured attempting to lift the siege of Leningrad. After his capture he defected to Germany and headed the Russian Liberation Army (Russkaya osvoboditel'naya armiya, ROA). Initially this army existed only on paper and was used by Germans to goad Red Army troops to surrender; only in 1944 did Heinrich Himmler, aware of Germany's shortage of manpower, arrange for Vlasov to form a real collaborationist army formed from Soviet prisoners of war. At the war's end, Vlasov changed sides again and ordered the ROA to aid the May 1945 Prague uprising against the Germans. He and the ROA then tried to escape to the Western Front, but were captured by Soviet forces with the United States' assistance. Vlasov was tortured,[2] tried for treason, and hanged.

Early career

Born in Lomakino, Nizhny Novgorod Governorate, Russian Empire, Vlasov was originally a student at a Russian Orthodox seminary. He quit the study of divinity after the Russian Revolution, briefly studying agricultural sciences instead, and in 1919 joined the Red Army fighting in the southern theatre in Ukraine, the Caucasus, and the Crimea during the Russian Civil War. He distinguished himself as an officer and gradually rose through the ranks of the Red Army.

Vlasov joined the Communist Party in 1930. Sent to China, he acted as a military adviser to Chiang Kai-shek from 1938 to November 1939. From February to May 1939 he was the advisor to Yan Xishan, the governor of Shanxi. Vlasov was also the chief of staff to the head of the Soviet military mission, General Aleksandr Cherepanov.[3] Upon his return, Vlasov served in several assignments before being given command of the 99th Rifle Division. After just nine months under Vlasov's leadership, and an inspection by Semyon Timoshenko, the division was recognized as one of the best divisions in the Army in 1940.[4] Timoshenko presented Vlasov with an inscribed gold watch, as he "found the 99th the best of all". The historian John Erickson says of Vlasov at this point that [he] "was an up-and-coming man".[5] In 1940, Vlasov was promoted to major general, and on June 22, 1941, when the Germans and their allies invaded the Soviet Union, Vlasov was commanding the 4th Mechanized Corps.

As a lieutenant general, he commanded the 37th Army near Kiev and escaped encirclement. He then played an important role in the defense of Moscow, as his 20th Army counterattacked and retook Solnechnogorsk. Vlasov's picture was printed (along with those of other Soviet generals) in the newspaper Pravda as that of one of the "defenders of Moscow". Vlasov was decorated on January 24, 1942, with the Order of the Red Banner for his efforts in the defence of Moscow. Vlasov was ordered to relieve the ailing commander Klykov after the Second Shock Army had been encircled.[6] After this success, Vlasov was put in command of the 2nd Shock Army of the Volkhov Front and ordered to lead the attempt to lift the Siege of Leningrad—the Lyuban-Chudovo Offensive Operation of January–April 1942.

On January 7, 1942, Vlasov's army had spearheaded the Lyuban offensive operation to break the Leningrad encirclement. Planned as a combined operation between the Volkhov and Leningrad Fronts on a 30 km frontage, other armies of the Leningrad Front (including the 54th) were supposed to participate at scheduled intervals in this operation. Crossing the Volkhov River, Vlasov's army was successful in breaking through the German 18th Army's lines and penetrated 70–74 km deep inside the German rear area.[7] However, the other armies (the Volkhov Front's 4th, 52nd, and 59th Armies, 13th Cavalry Corps, and 4th and 6th Guards Rifle Corps, as well as the 54th Army of the Leningrad Front) failed to exploit Vlasov's advances and provide the required support, and Vlasov's army became stranded. Permission to retreat was refused. With the counter-offensive in May 1942, the Second Shock Army was finally allowed to retreat, but by now, too weakened, it was surrounded and in June 1942 virtually annihilated during the final breakout at Myasnoi Bor.[8]

German prisoner

After Vlasov's army was surrounded, he himself was offered an escape by aeroplane. The general refused and hid in German-occupied territory; ten days later, on July 12, 1942, a local farmer exposed him to the Germans. Vlasov's opponent and captor, general Georg Lindemann, interrogated him about the surrounding of his army and details of battles, then "had Vlasov imprisoned in occupied Vinnytsia."

While in prison, Vlasov met Captain Wilfried Strik-Strikfeldt, a Baltic German who was attempting to foster a Russian Liberation Movement. Strik-Strikfeldt had circulated memos to this effect in the Wehrmacht. Strik-Strikfeldt, who had been a participant in the White movement during the Russian Civil War, persuaded Vlasov to become involved in aiding the German advance against the rule of Joseph Stalin and Bolshevism. With Lieutenant Colonel Vladimir Boyarsky, Vlasov wrote a memo shortly after his capture to the German military leaders suggesting cooperation between anti-Stalinist Russians and the German Army.

In 2016, in his habilitation thesis, Russian historian Kirill Alexandrov analyzed the careers of 180 Soviet generals and officers who joined the Vlasov army. He concluded that most of them personally experienced atrocities committed by the NKVD during the Great Purge and previous purges in the Red Army, which made them disillusioned with the leadership of Stalin and motivated them to defect to the Nazis. Alexandrov's work was reported to the FSB by Russian and Soviet nationalists as "inciting hatred" but his university, regardless of the political pressure, voted in favor of its scientific value.[9]

Defection

Vlasov was taken to Berlin under the control of the Wehrmacht Propaganda Department. While there, he and other Soviet officers began drafting plans for the creation of a Russian provisional government and the recruitment of a Russian army of liberation under Russian command.

Vlasov founded the Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia, in hopes of creating the Russian Liberation Army—known as ROA (from Russkaya Osvoboditel'naya Armiya).

In the spring of 1943, Vlasov wrote an anti-Bolshevik leaflet known as the "Smolensk Proclamation", which was dropped from aircraft by the millions on Soviet forces and Soviet-controlled soil. In March of the same year, Vlasov also published an open letter titled "Why I Have Taken Up the Struggle Against Bolshevism".

Even though no Russian Liberation Army yet existed, the Nazi propaganda department issued Russian Liberation Army patches to Russian volunteers and tried to use Vlasov's name in order to encourage defections. Several hundred thousand former Soviet citizens served in the German army wearing this patch, but never under Vlasov's own command.

Vlasov was permitted to make several trips to German-occupied Soviet Union: most notably, to Pskov, Russia, where Russian pro-German volunteers paraded. The populace's reception of Vlasov was mixed. While in Pskov, Vlasov dealt himself a nearly fatal political blow by referring to the Germans as mere "guests" during a speech, which Hitler found belittling. Vlasov was even put under house arrest and threatened with being handed over to the Gestapo. Despondent about his mission, Vlasov threatened to resign and return to the POW camp, but was dissuaded at the last minute by his confidants.

According to Varlam Shalamov and his tale The Last Battle of Major Pugachov, Vlasov emissaries lectured to the Russian prisoners of war, explaining to them that their government had declared them all traitors, and that escaping was pointless. As Vlasov proclaimed, even if the Soviets succeeded, Stalin would send them to Siberia.[10] Only in September 1944 did Germany, at the urging of Heinrich Himmler, initially a virulent opponent of Vlasov, finally permit Vlasov to raise his Russian Liberation Army. Vlasov formed and chaired the Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia, proclaimed by the Prague Manifesto on 14 November 1944. Vlasov also hoped to create a Pan-Slavic liberation congress, but Nazi political officials would not permit it.

Commander of the ROA

Vlasov's only combat against the Red Army took place on February 11, 1945, on the river Oder. After three days of battle against overwhelming forces, the First Division of the ROA was forced to retreat and marched southward to Prague, in German-controlled Bohemia.

On May 6, 1945, Vlasov received a request from the commander of the First Division, General Sergei Bunyachenko, for permission to turn his weapons against the Nazi SS forces and aid Czech resistance fighters in the Prague uprising. Vlasov at first disapproved, then reluctantly allowed Bunyachenko to proceed. Some historians maintain it was the bitterness of the ROA against the Germans which caused them to switch sides once again, while other historians believe the sole purpose of this action was to win favor from the western Allies and possibly even the Soviet side, in the light of the nearly completed military annihilation of the German Reich.

Two days later, the First Division was forced to leave Prague as Communist Czech partisans began arresting ROA soldiers in order to hand them over to the Soviets for execution. Vlasov and the rest of his forces, trying to evade the Red Army, attempted to head west to surrender to the Allies in the closing days of the war in Europe.[11]

Capture by Soviet forces, trial, and execution

Vlasov's division, commanded by General Sergei Bunyachenko, was captured 40 kilometres (25 mi) southeast of Plzeň by the Soviet 25th Tank Corps, after their attempt to surrender to US troops was rejected. Captain M. I. Yakushev of the 162nd Tank Brigade had Vlasov dragged out of his car, put on a tank and driven straight to the Soviet 13th Army HQ. Vlasov was then transported from the 13th Army HQ to Marshal Ivan Konev's command post in Dresden, and from there sent immediately to Moscow.[13]

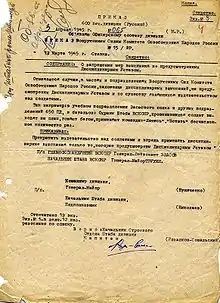

Vlasov was confined in Lubyanka prison where he was interrogated. A trial was held, beginning on 30 July 1946 and was presided over by Viktor Abakumov who sentenced him and eleven other senior officers from his army to death for high treason.

.jpg.webp)

Vlasov was executed by hanging on 1 August 1946. His execution was among the last death sentences in the Soviet Union carried out by hanging, after which executions were conducted only by shooting.

Memorial

A memorial dedicated to General Vlasov was erected at the Novo-Diveevo Russian Orthodox convent and cemetery in Nanuet, New York, US. Twice annually, on the anniversary of Vlasov's execution and on the Sunday following Orthodox Easter, a memorial service is held for Vlasov and the forces of the Russian Liberation Army.

Review of his case

In 2001, a Russian social organization, "For Faith and Fatherland", applied to the Russian Federation's military prosecutor for a review of Vlasov's case,[14] saying that "Vlasov was a patriot who spent much time re-evaluating his service in the Red Army and the essence of Stalin's regime before agreeing to collaborate with the Germans".[15] The military prosecutor concluded that the law of rehabilitation of victims of political repressions did not apply to Vlasov and refused to consider the case again. However, Vlasov's Article 58 conviction for anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda was vacated.[16]

See also

References

- ↑ Михаил Алексеевич Меандров. Штрихи к портрету // К. М. Александров. Против Сталина. Сборник статей и материалов. СПб, 2003.

- ↑ Gordievsky & Andrew (1990). KGB : The Inside Story. Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. p. 343. ISBN 0340485612.

- ↑ Andreyev 1987, p. 21.

- ↑ Коллектив авторов. «Великая Отечественная. Командармы. Военный биографический словарь» — М.; Жуковский: Кучково поле, 2005. ISBN 5-86090-113-5

- ↑ John Erickson, The Soviet High Command, MacMillan, 1962, p.558

- ↑ Bellamy, Absolute War, pg 384

- ↑ Meretskov, On the service of the nation, Ch.6

- ↑ Erickson, Road to Stalingrad, 2003, p.352. See also p.381, where Erickson describes 2 Shock after this operation as 'an army brought back from the dead.'

- ↑ Резунков, Виктор (2016-05-03). "ФСБ и генерал Власов". Радио Свобода (in Russian). Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ↑ Gerald Reitlinger. The House Built on Sand. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London (1960) ASIN: B0000CKNUO. pp. 90, 100–101.

- ↑ "Рубать немцев, освободить Прагу"

- ↑ Žaček, Pavel (2014). "Prague under the armor of the Vlasovs - the Czech May Uprising in photography" (in Czech). Czech Republic: Mladá Fronta. ISBN 9788020426819.

- ↑ Konev, I.S. (1971). "Year of Victory". Progress Publishers. pp. 230–231.

- ↑ Valeria Korchagina and Andrei Zolotov Jr.It's Too Early To Forgive Vlasov The St. Petersburg Times. 6 Nov 2001.

- ↑ "It's Too Early to Forgive Vlasov | the St. Petersburg Times | the leading English-language newspaper in St. Petersburg". Archived from the original on 2014-02-06. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ↑ РОА: предатели или патриоты?

Literature and film

Books:

- Andreyev, Catherine (1987). Vlasov and the Russian Liberation Movement. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521389600.

- Wilfried Strik-Strikfeldt: Against Stalin and Hitler. Memoir of the Russian Liberation Movement 1941–5. Macmillan, 1970, ISBN 0-333-11528-7

- Russian version of the above: Вильфрид Штрик-Штрикфельдт: Против Сталина и Гитлера. Изд. Посев, 1975, 2003. ISBN 5-85824-005-4

- Sven Steenberg: Wlassow. Verräter oder Patriot? Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, Köln 1968.

- Sergej Frölich: General Wlassow. Russen und Deutsche zwischen Hitler und Stalin.

- Joachim Hoffmann: Die Tragödie der 'Russischen Befreiungsarmee' 1944/45. Wlassow gegen Stalin. Herbig Verlag, 2003 ISBN 3-7766-2330-6.

- Jurgen Thorwald: The Illusion: Soviet Soldiers in Hitler's Armies. English translation, 1974.

- Martin Berger: "Impossible alternatives". The Ukrainian Quarterly, Summer-Fall 1995, pp. 258–262. [review of Catherine Andrevyev: Vlasov and the Russian liberation movement]

Documentaries:

- General for Two Devils 1995

- Europe Central by William T Vollmann

- Angels of Death 1998, director: Leo de Boer.

External links

- "It's Too Early To Forgive Vlasov", The St. Petersburg Times, November 6, 2001

- Władysław Anders and Antonio Muňoz: "Russian Volunteers in the German Wehrmacht in WWII" (describes role of Vlasov)

- Congress of Russian Americans article on Vlasov

- Newspaper clippings about Andrey Vlasov in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW