.jpg.webp)

Science and technology in Germany has a long and illustrious history, and research and development efforts form an integral part of the country's economy. Germany has been the home of some of the most prominent researchers in various scientific disciplines, notably physics, mathematics, chemistry and engineering.[1] Before World War II, Germany had produced more Nobel laureates in scientific fields than any other nation, and was the preeminent country in the natural sciences.[2][3]

The German language was an important language of science from the late 19th century through the end of World War II. After the war, because so many scientific researchers and teachers' careers had been ended either by Nazi Germany, the denazification process, the American Operation Paperclip and Soviet Operation Osoaviakhim, or simply losing the war, "Germany, German science, and German as the language of science had all lost their leading position in the scientific community."[4]

Today, scientific research in the country is supported by industry, the network of German universities and scientific state-institutions such as the Max Planck Society and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. The raw output of scientific research from Germany consistently ranks among the world's highest.[5] Germany was declared the most innovative country in the world in the 2020 Bloomberg Innovation Index and was ranked 8th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[6]

Institutions

Foundations

- Alexander von Humboldt Foundation

- Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)

- Federal Ministry for Economics and Technology (BMWi)

- German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), promoting international exchange of scientists and students)

National science libraries

Research organizations

- Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres (complex systems und lage-scale research)

- Fraunhofer Society (applied research and mission oriented research)

- Leibniz Association (fundamental and applied research)

- Max Planck Society (fundamental research)

- Gesellschaft für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik

Prize committees

The Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize is granted to ten scientists and academics every year. With a maximum of €2.5 million per award it is one of highest endowed research prizes in the world.[7] The prize and the mentioned organization above is named after the German polymath and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), who was a contemporary and competitor of Isaac Newton (1642–1727).

Scientific fields

Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) was one of the originators of the so-called Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries. He was an astronomer, physicist, mathematician and natural philosopher. Johannes Kepler discovered the laws according to which planets are moving around the Sun, who were called Kepler's laws after him. With his introduction to calculating with logarithms, Kepler contributed to the spread of this type of calculation. In mathematics, a numerical method for calculating integrals was named former Kepler's barrel rule.[8] He made optics to a subject of scientific investigation and confirmed the discoveries made with the telescope by his contemporary Galileo Galilei. He worked on the theory of the telescope and invented the refracting astronomical or Keplerian telescope, which involved a considerable improvement over the Galilean telescope.[9]

Physics

.png.webp)

The work of Albert Einstein and Max Planck was crucial to the foundation of modern physics, which Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger developed further.[10] They were preceded by such key physicists as Hermann von Helmholtz, Joseph von Fraunhofer, and Gabriel Daniel Fahrenheit, among others. Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovered X-rays, an accomplishment that made him the first winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901[11] and eventually earned him an element name, roentgenium. Heinrich Rudolf Hertz's work in the domain of electromagnetic radiation were pivotal to the development of modern telecommunication.[12] Mathematical aerodynamics was developed in Germany, especially by Ludwig Prandtl.

Paul Forman in 1971 argued the remarkable scientific achievements in quantum physics were the cross-product of the hostile intellectual atmosphere whereby many scientists rejected Weimar Germany and Jewish scientists, revolts against causality, determinism and materialism, and the creation of the revolutionary new theory of quantum mechanics. The scientists adjusted to the intellectual environment by dropping Newtonian causality from quantum mechanics, thereby opening up an entirely new and highly successful approach to physics. The "Forman Thesis" has generated an intense debate among historians of science.[13][14]

Chemistry

Justus von Liebig (1803 – 1873) made major contributions to agricultural and biological chemistry, and is considered one of the principal founders of organic chemistry.[15]

At the start of the 20th century, Germany garnered fourteen of the first thirty-one Nobel Prizes in Chemistry, starting with Hermann Emil Fischer in 1902 and until Carl Bosch and Friedrich Bergius in 1931.[11]

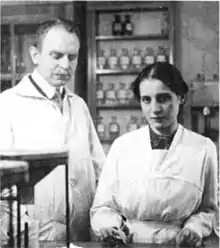

Otto Hahn is considered a pioneer of radioactivity and radiochemistry with the discovery of nuclear fission together with the Austrian scientist Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann in 1938, the scientific and technological basis for the utilization of atomic energy.

The bio-chemist Adolf Butenandt independently worked out the molecular structure of the primary male sex hormone of testosterone and was the first to successfully synthesize it from cholesterol in 1935.

Engineering

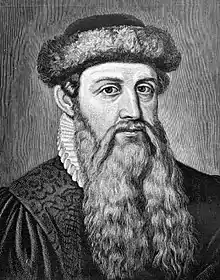

Germany has been the home of many famous inventors and engineers, such as Johannes Gutenberg, who is credited with the invention of movable type printing in Europe; Hans Geiger, the creator of the Geiger counter; and Konrad Zuse, who built the first electronic computer.[16] German inventors, engineers and industrialists such as Zeppelin, Siemens, Daimler, Diesel, Otto, Wankel, Von Braun and Benz helped shape modern automotive and air transportation technology including the beginnings of space travel.[17][18] The engineer Otto Lilienthal laid some of the fundamentals for the science of aviation.[19]

The physicist and optician Ernst Abbe (1840–1905) founded in the 19th century together with the entrepreneurs Carl Zeiss (1840–1905) and Otto Schott (1851–1935) the basics of modern Optical engineering and developed many optical instruments like microscopes and telescopes. Since 1899 he was the sole owner of the Carl Zeiss AG and played a decisive role of setting up the enterprise Jenaer Glaswerk Schott & Gen (today Schott AG). These enterprises are very successful worldwide up to our time (21st century).

In the Thirties of the 20th century the electrical engineers Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll developed at the "Technische Hochschule zu Berlin" the first electron microscope.[20]

Biological and earth sciences

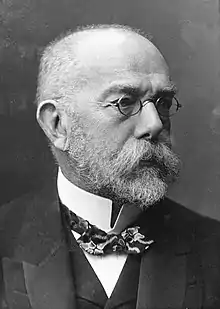

Emil Behring, Ferdinand Cohn, Paul Ehrlich, Robert Koch, Friedrich Loeffler and Rudolph Virchow, six key figures in microbiology, were from Germany. Alexander von Humboldt's (1769–1859) work as a natural scientist and explorer was foundational to biogeography, he was one of the outstanding scientists of his time and a shining example for Charles Darwin.[21] Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) was an eclectic Russian-born botanist and climatologist who synthesized global relationships between climate, vegetation and soil types into a classification system that is used, with some modifications, to this day.[22] The Frankfurt surgeon, botanist, microbiologist, and mycologist Anton de Bary (1831 – 1888) laid one of the fundamentals of the plant pathology and was one of the discoverer of the symbiosis of organisms.

Ernst Haeckel (1834 – 1919) discovered, described and named thousands of new species, mapped a tree of life relating all life forms and coined many terms in biology, for example ecology and phylum. His published artwork of different lifeforms includes over 100 detailed, multi-colour illustrations of animals and sea creatures, collected in his Kunstformen der Natur ("Art Forms of Nature"), an international bestseller and a book which would go on to influence the Art Nouveau (German Jugendstil, youth style). But Haeckel was also a promoter of scientific racism[23] and embraced the idea of Social Darwinism.

Alfred Wegener (1880–1930), a similarly interdisciplinary scientist, was one of the first people to hypothesize the theory of continental drift which was later developed into the overarching geological theory of plate tectonics.

Psychology

Wilhelm Wundt is credited with the establishment of psychology as an independent empirical science through his construction of the first laboratory at the University of Leipzig in 1879.[24]

In the beginning of the 20th century, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute founded by Oskar and Cécile Vogt was among the world's leading institutions in the field of brain research.[25] They collaborated with Korbinian Brodmann to map areas of the cerebral cortex.

After the National Socialistic laws banning Jewish doctors in 1933, the fields of neurology and psychiatry faced a decline of 65% of its professors and teachers. The research shifted to a 'Nazi neurology', with subjects such as eugenics or euthanasia.[25]

Humanities

Besides natural sciences, German researchers have added much to the development of humanities. Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717 – 1768) was a German art historian and archaeologist, "the prophet and founding hero of modern archaeology".[26] Heinrich Schliemann was a wealthy businessman and a devotee of the historicity of places mentioned in the works of Homer and an archaeological excavator of Hisarlik (since 1871), now presumed to be the site of Troy, along with the Mycenaean sites Mycenae and Tiryns. Theodor Mommsen is widely counted as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th century; his work regarding Roman history is still of fundamental importance for contemporary research. Max Weber was together with Karl Marx among the most important theorists of the development of modern Western society and is regarded as one of the founder of the Sociology.

Contemporary examples are the philosopher Jürgen Habermas, the Egyptologist Jan Assmann, the sociologist Niklas Luhmann, the historian Reinhart Koselleck and the legal historian Michael Stolleis. In order to promote the international visibility of research in these fields a new prize, Geisteswissenschaften International, was established in 2008. It serves the translation of studies in humanities into English.[27]

Personality

Hildegard of Bingen, considered by scholars to be the founder of scientific natural history in Germany.[28]

Hildegard of Bingen, considered by scholars to be the founder of scientific natural history in Germany.[28] Georgius Agricola gave chemistry it´s modern name. Generally referred to as the Father of Mineralogy and the founder of geology as a scientific discipline.[29][30]

Georgius Agricola gave chemistry it´s modern name. Generally referred to as the Father of Mineralogy and the founder of geology as a scientific discipline.[29][30] Johannes Gutenberg, inventor of the printing press, named the most important invention of the second millennium.[31]

Johannes Gutenberg, inventor of the printing press, named the most important invention of the second millennium.[31] Johannes Kepler, one of the founders and fathers of modern astronomy, the scientific method,natural and modern science.[32][33][34]

Johannes Kepler, one of the founders and fathers of modern astronomy, the scientific method,natural and modern science.[32][33][34].jpg.webp) Johann Joachim Winckelmann, founder of modern archaeology,[35] father of the discipline of art history[36] and father of Neoclassicism.[37]

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, founder of modern archaeology,[35] father of the discipline of art history[36] and father of Neoclassicism.[37] Alexander von Humboldt, seen as "the father of ecology" and "the father of environmentalism".[38][39]

Alexander von Humboldt, seen as "the father of ecology" and "the father of environmentalism".[38][39] Carl Friedrich Gauss, referred to as one of the most important mathematicians of all time.[40]

Carl Friedrich Gauss, referred to as one of the most important mathematicians of all time.[40]

Otto Lilienthal, who has been referred to as the "father of aviation"[49][50][51] or "father of flight".[52]

Otto Lilienthal, who has been referred to as the "father of aviation"[49][50][51] or "father of flight".[52]

Fritz Haber invented the Haber–Bosch process. It is estimated that it provides the food production for nearly half of the world's population.[58][59] Haber has been called one of the most important scientists and chemists in human history.[60][61][62]

Fritz Haber invented the Haber–Bosch process. It is estimated that it provides the food production for nearly half of the world's population.[58][59] Haber has been called one of the most important scientists and chemists in human history.[60][61][62] Albert Einstein, who has been called the greatest physicist of all time and one of the fathers of modern physics.[63][64]

Albert Einstein, who has been called the greatest physicist of all time and one of the fathers of modern physics.[63][64].jpg.webp)

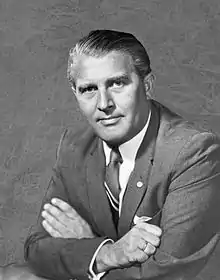

Wernher von Braun, who co-developed the V-2 rocket, the first artificial object to travel into space. Described by others as the "father of space travel",[67] the "father of rocket science",[68] or the "father of the American lunar program".[69]

Wernher von Braun, who co-developed the V-2 rocket, the first artificial object to travel into space. Described by others as the "father of space travel",[67] the "father of rocket science",[68] or the "father of the American lunar program".[69]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Back to the Future: Germany - A Country of Research". German Academic Exchange Service. 23 February 2005. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ↑ National Science Nobel Prize shares 1901-2009 by citizenship at the time of the award and by country of birth. From J. Schmidhuber (2010), Evolution of National Nobel Prize Shares in the 20th Century Archived 27 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine at arXiv:1009.2634v1

- ↑ Swedish academy awards. ScienceNews web edition, Friday, 1 October 2010: http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/63944/title/Swedish_academy_awards

- ↑ Hammerstein, Notker (2004). "Epilogue: Universities and War in the Twentieth Century". In Rüegg, Walter (ed.). A History of the University in Europe: Volume Three, Universities in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries (1800–1945). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 637–672. ISBN 9781139453028. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ↑ Top 20 Country Rankings in All Fields, 2006, Thomson Corporation, retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ↑ Dutta, Soumitra; Lanvin, Bruno; Wunsch-Vincent, Sacha; León, Lorena Rivera; World Intellectual Property Organization. "Global Innovation Index 2023". WIPO. doi:10.34667/tind.46596. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ↑ "Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize". DFG. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ↑ J. V. Field (April 1999). "Johannes Kepler - Biography". London: University of St Andrews, Scotland. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ↑ Di Liscia, Daniel A. (17 September 2021). "Johannes Kepler (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ↑ Roberts, J. M. The New Penguin History of the World, Penguin History, 2002. Pg. 1014. ISBN 0-14-100723-0

- 1 2 "The Alfred B. Nobel Prize Winners, 1901-2003". The World Almanac and Book of Facts. 2006. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2007 – via History Channel.

- ↑ "Historical figures in telecommunications". International Telecommunication Union. 14 January 2004. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ↑ Paul Forman, "Weimar Culture, Causality, and Quantum Theory, 1918-1927: Adaptation by German Physicists and Mathematicians to a Hostile Intellectual Environment," Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 3 (1971): 1-116

- ↑ Helge Kragh, Quantum generations: a history of physics in the twentieth century (2002) ch 10

- ↑ Jackson, Catherine Mary (December 2008). Analysis and Synthesis in Nineteenth-Century Organic Chemistry (PDF) (PhD). University of London. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ↑ Horst, Zuse. "The Life and Work of Konrad Zuse". Everyday Practical Electronics (EPE) Online. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ↑ "Automobile". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia. 2006. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ↑ The Zeppelin Archived 1 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. Retrieved 2 January 2007

- ↑ Bernd Lukasch. "From Lilienthal to the Wrights". Anklam: Otto-Lilienthal-Museum. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ↑ Hawkes, Peter W. (1 July 1990). "Ernst Ruska". Physics Today. 43 (7): 84–85. Bibcode:1990PhT....43g..84H. doi:10.1063/1.2810640. ISSN 0031-9228.

- ↑ The Natural History Legacy of Alexander von Humboldt (1769 to 1859) Humboldt Field Research Institute and Eagle Hill Foundation. Retrieved 2 January 2007

- ↑

- Allaby, Michael (2002). Encyclopedia of Weather and Climate. New York: Facts On File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-4071-0.

- ↑ Hawkins, Mike (1997). Social Darwinism in European and American Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 140.

- ↑ Kim, Alan. Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 16 June 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2007

- 1 2 European neurology German Neurology and the ‘Third Reich’ Michael Martin a Heiner Fangerau a Axel Karenberg b a Institute of the History, Philosophy and Ethics of Medicine, Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf , and b Institute for the History of Medicine and Medical Ethics, Medical Faculty, University of Cologne, Cologne , Germany

- ↑ Boorstin, Daniel J. (1983). The Discoverers. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-72625-0.

- ↑ GINT. "Geisteswissenschaften International Nonfiction Translators Prize". boersenverein.de. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ↑ Jöckle, Clemens (2003). Encyclopedia of Saints. Konecky & Konecky. p. 204.

- ↑ "Georgius Agricola". University of California - Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ↑ Rafferty, John P. (2012). Geological Sciences; Geology: Landforms, Minerals, and Rocks. New York: Britannica Educational Publishing, p. 10. ISBN 9781615305445

- ↑ "Gutenberg, Man of the Millennium". 1,000+ People of the Millennium and Beyond. 2000. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012.

- ↑ "DPMA | Johannes Kepler".

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ https://micro.magnet.fsu.edu/optics/timeline/people/kepler.html

- ↑ Boorstin, 584

- ↑ Robinson, Walter (February 1995). "Introduction". Instant Art History. Random House Publishing Group. p. 240. ISBN 0-449-90698-1.

The father of official art history was a German named Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–68).

- ↑ https://humanistic-europe.com/winckelmann/

- ↑ "The Father of Ecology". 19 February 2020.

- ↑ "The Forgotten Father of Environmentalism". The Atlantic. 23 December 2015.

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Carl-Friedrich-Gauss

- ↑ Fleming, Alexander (1952). "Freelance of Science". British Medical Journal. 2 (4778): 269. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4778.269. PMC 2020971.

- ↑ Tan, S. Y.; Berman, E. (2008). "Robert Koch (1843-1910): father of microbiology and Nobel laureate". Singapore Medical Journal. 49 (11): 854–855. PMID 19037548.

- ↑ Gradmann, Christoph (2006). "Robert Koch and the white death: from tuberculosis to tuberculin". Microbes and Infection. 8 (1): 294–301. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2005.06.004. PMID 16126424.

- ↑ https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=245261433654285

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch

- ↑ "Karl Benz: Father of the Automobile". YouTube.

- ↑ "The Father of automobile gave us Mercedes Benz and Merc gave us fascinating facts. Check out a few here! - ET Auto".

- ↑ Fanning, Leonard M. (1955). Carl Benz: Father of the Automobile Industry. New York: Mercer Publishing.

- ↑ "DPMA | Otto Lilienthal". Dpma.de. 2 December 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ↑ "In perspective: Otto Lilienthal". Cobaltrecruitment.co.uk. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ↑ "Remembering Germany's first "flying man"". The Economist. 20 September 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ↑ "Otto Lilienthal, the Glider King". SciHi BlogSciHi Blog. 23 May 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ↑ https://www.historyisnowmagazine.com/blog/2014/3/2/the-scientist-who-world-war-i-wrote-out-of-history

- ↑ "Mit Nobelpreisträger Karl Ferdinand Braun begann das Fernsehzeitalter". Die Welt. 1 January 1970. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ↑ Peter Russer (2009). "Ferdinand Braun — A pioneer in wireless technology and electronics". 2009 European Microwave Conference (EuMC). pp. 547–554. doi:10.23919/EUMC.2009.5296324. ISBN 978-1-4244-4748-0. S2CID 34763002.

- ↑ Rundfunk, Bayerischer (20 April 2018). "Karl Ferdinand Braun: Der Wegbereiter des Fernsehens | BR Wissen". Br.de. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ↑ "Siegeszug des Fernsehens: Vor 125 Jahre kam die Braunsche Röhre zur Welt". Geo.de. 15 February 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ↑ Smil, Vaclav (2004). Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 156. ISBN 9780262693134.

- ↑ Flavell-While, Claudia. "Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch – Feed the World". www.thechemicalengineer.com. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ↑ "The Man Who Killed Millions and Saved Billions". YouTube.

- ↑ "Seven Billion Humans: The World Fritz Haber Made". 2 November 2011.

- ↑ "Fritz Haber's Experiments in Life and Death".

- ↑ "Physics: past, present, future". Physics World. 6 December 1999. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ↑ https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=213500586521910

- ↑ Bellis, Mary (15 May 2019) [First published 2006 at inventors.about.com/library/weekly/aa050298.htm]. "Biography of Konrad Zuse, Inventor and Programmer of Early Computers". thoughtco.com. Dotdash Meredith. Archived from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

Konrad Zuse earned the semiofficial title of 'inventor of the modern computer'

- ↑ "Who is the Father of the Computer?". computerhope.com.

- ↑ "von Braun, Wernher: National Aviation Hall of Fame". Nationalaviation.org. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ↑ "A Guide to Wernher von Braun's Life". Apollo11space.com. December 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ↑

References

- Competing Modernities: Science and Education, Kathryn Olesko and Christoph Strupp. (A comparative analysis of the history of science and education in Germany and the United States)

- English section of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research's website

- Germany's science and research landscape

- Articles and dossiers about Research and Technology in Germany, Goethe-Institut

- Audretsch, D. B., Lehmann, E. E., & Schenkenhofer, J. (2018). Internationalization strategies of hidden champions: lessons from Germany. Multinational Business Review.