Jacopo Caraglio, Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio or Gian Giacomo Caraglio (c. 1500/1505 – 26 August 1565) known also as Jacobus Parmensis and Jacobus Veronensis was an Italian engraver, goldsmith and medallist, born at Verona or Parma. His career falls easily into two rather different halves: he worked in Rome from 1526 or earlier as an engraver in collaboration with leading artists, and then in Venice, before moving to spend the rest of his life as a court goldsmith in Poland, where he died.[1]

In Italy, he was one of the first reproductive printmakers, rendering versions of specially made drawings (mostly) or paintings rather than creating new works for the print medium, although detailed comparison of surviving drawings with the prints made from them show he had input into the creative process.[2] He was in Rome at the brief period when the small but flourishing printmaking industry created by Raphael working with engravers to diffuse his work had been disrupted by Raphael's sudden death in 1520, cutting off the supply of new designs, and other artists were recruited fill the gap.[3]

A. Hyatt Mayor describes Caraglio as "the most individual member of the group", who had a particular influence on French printmaking of the First School of Fontainebleau, although unlike Rosso he never went there.[4] His skill in engraving was available to artists developing the early style of full-blown Mannerism, and played a significant role in diffusing advanced Mannerist style around Italy and Europe.[5]

Life

Italy

Caraglio was probably trained as a goldsmith before learning advanced engraving techniques from Marcantonio Raimondi, in whose circle in Rome he first appears in records in 1526. Raphael's former associate il Baviera, who probably acted as his "publisher", introduced him to Rosso Fiorentino, with whom he collaborated on numerous prints, including sets of The Labours of Hercules (Bartsch 44–49), Pagan Divinities in Niches (Bartsch 24–43) and Loves of the Gods (Bartsch 9-23). He engraved gems and designed and cast medals as well as producing reproductive engravings after the works of Rosso, Parmigianino, Giulio Romano, Baccio Bandinelli, Raphael, Titian, Michelangelo, and Perino del Vaga. Bartsch records 65 prints, though missing perhaps another five. His style is summarized by Françoise Jestaz: "Numbered with Agostino dei Musi and Marco Dente in the Roman school of engravers in the circle of Raimondi, Caraglio showed a greater freedom of line. With Rosso Fiorentino and Parmigianino, he discovered new modelling effects with subtler lighting and more animated forms, for example in his engraving of Diogenes (b. 61) and in the first state of the Rape of the Sabine Women (b. 63)."[6]

He worked from drawings created by Rosso and others for the purpose, and a proof of a print after Rosso at Chatsworth House has a landscape background in pen added to printed figures, presumably by one of the two, Rosso's initial drawing having only included the figures. He worked closely with Rosso and Parmigianino, and a number of their drawings for his prints survive, usually at the same size and in the reverse sense of the prints.[7]

His Loves of the Gods were, with I Modi, one of the "two best-known series of Renaissance erotic prints", and altogether one of the most successful Renaissance print series. Unlike I Modi they successfully avoided censorship by avoiding depicting genitals and actual penetration in favour of "slung leg" positions, and by virtue of their ostensibly mythological subjects. This was despite one showing two males, Apollo and Hyacinthus, together, if not actually making love. Both sets were much copied, with five different copies of Caraglio's set, and in 1550 a dealer bought 250 sets of French copies, a very large number for the time.[8] They were even used as sources for illustrations in medical textbooks later in the century,[9] as well as one of a set of Flemish tapestries of about 1550, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[10] The first two designs were by Rosso, but the pair then fell out, and Pierino did most of the rest, probably with an unknown weaker artist contributing some designs.[11] Caraglio's prints were also often used as sources to be expanded into designs for maiolica.

Caraglio fled to Venice on the Sack of Rome in 1527, in which his colleague Marco Dente was killed, and the whole circle dispersed.[4] He seems to have remained there until at least 1537, working with Titian and others.

Poland

In 1539 he is recorded at the Polish court of Sigismund I. He had probably been introduced there through Pietro Aretino, a friend in Venice, and his contacts with the circle of the Italian-born Polish Queen Bona Sforza (1494–1557), such as Allesandro Pessenti, Bona's organist. In Poland he mostly worked for the court on medals, gems and goldsmithing rather than printmaking.[12] Vasari presents this as, in Caraglio's view, a step up the hierarchy of genres and as offering a better social position, and indeed the status of printmaking was on the decline as the merely reproductive print, commissioned by publishers, had largely driven out the original print.[13]

The Renaissance medal was a novelty in the Polish court, but promoted by Bona, and in July 1539 Caraglio wrote to Aretino enclosing two medals, one of Pesenti and the other of Bona, the first evidence of his presence in Poland. Some copies of the former survive, but none of Bona's medal, as of some other recorded ones Caraglio made in Poland.[14] Only one copy survives of the medal he made of Sigismund I in 1538 from the gold sent as dowry for the wedding of Elizabeth of Austria (1526–1545), the first wife of the future Sigismund II, which was handed out to wedding guests.[15]

Caraglio was appointed royal goldsmith to Sigismund I in 1545, with a salary (probably more a retainer in modern terms) of 60 zloty, and continued serving under Sigismund II Augustus from 1548, when Sigismund I died. Having taken citizenship in Kraków, he was knighted (as equitatis aureati), with a patent of nobility, in April 1552, after which he made a brief return trip to Italy. It was presumably on this visit that the portrait now in the Wawel Castle in Kraków by Paris Bordone was made to celebrate his knighthood. The royal white eagle has the monogram of Sigismund II on its chest, and the upper background shows the Roman amphitheatre at Verona; on the bench are the tools of a goldsmith rather than a printmaker.[16]

In 1565, he is recorded in a court action over a debt of 80 zloties owed by another Italian emigre artist, the sculptor Giammaria Mosca, known as "Padovano", which Caraglio claimed from the executors of yet another Italian, a royal doctor, whose tomb Padovano had completed.[17] Caraglio married a Polish woman and acquired property, and died in Kraków, where he is buried in the Carmelite church. Vasari apparently did not know this, but probably knew that he was buying land near Parma in anticipation of a retirement that never arrived.[18]

He was also known as Cahalius or Jacobus Veronensis or Parmensis, the latter presumably after his estate near Parma, and these were used to sign some plates.[19] Caraglio has never been the subject of a monograph.[20]

Works

A small number of identifiable surviving works other than prints include signed intaglios in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris (the Annunciation to the Shepherds in rock crystal) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Queen Bona),[21] and an unsigned attributed piece in the Ambrosiana in Milan (Bona in crystal),[22] medals in Padua and elsewhere, and cameos in Munich (illustrated) and elsewhere.[23] He also produced relief plaquettes in bronze.

About 70 prints by Caraglio are known, from 1526 to 1551. They include:[24]

- Set of 15 Loves of the Gods (Bartsch 9-23), 1527, 12 after Perino del Vaga, 2 after Rosso.[25]

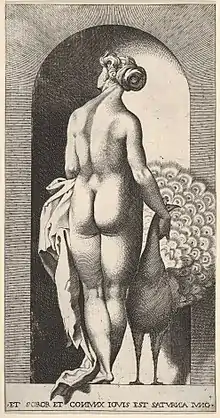

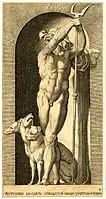

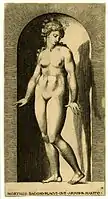

- Set of 20 Pagan Divinities in Niches (Bartsch 24–43) after Rosso, one dated 1526,[26]

- Set of The Labours of Hercules (Bartsch 44–49), after Rosso,[26] including Hercules piercing with his Arrows the Centaur Nessus; Hercules slaying Cacus

- Mars and Venus after Rosso's drawing in the Louvre, c. 1530 - now mostly thought not to be by Caraglio.[27]

- A Battle with the Shield and Lance; The Virgin kneeling, with the Infant and St. Ann; and Holy Family after Raphael.

- Diogenes (Bartsch 3); Alexander and Roxana; Martyrdom of SS. Peter and Paul; Portrait of Pietro Aretino; and Marriage of the Virgin after Parmigianino.

- The Virgin and Infant, under an Orange Tree (to his own design).

- The Annunciation and The Punishment of Tantalus; after Titian.

- The Rape of Ganymede after Michelangelo.

- Anatomical Figure holding skull; Nymphs and Young Men in Garden; and Rape of Sabines after Rosso Fiorentino.

- The Triumph of the Muses over Pierides:

- The Death of Meleager and The Creation; after Perino del Vaga.

- Portrait of Aretino.[28]

Fury, 1524-25

Fury, 1524-25

_Godenliefden_(serietitel)%252C_RP-P-OB-35.619.jpg.webp) Amor and Psyche from the Loves of the Gods, 1527

Amor and Psyche from the Loves of the Gods, 1527 Alexander the Great and Roxane, after Raphael

Alexander the Great and Roxane, after Raphael Cameo of Bona Sforza

Cameo of Bona Sforza Cameo of Sigismund II Augustus

Cameo of Sigismund II Augustus

Notes

- ↑ Jestaz; Pon, 150 for his death place, still uncertain in earlier sources.

- ↑ Landau, 120-121

- ↑ Landau, 130, 154, 159, 287

- 1 2 Mayor, 341

- ↑ Shearman, 64, 67, 194-195

- ↑ Jestaz; Mayor, 341; Image of Diogenes after Parmigianino

- ↑ Landau, 130, 154, 159, 287; Bury, 15 on the Chatsworth drawing

- ↑ Landau, 297-298 (quoted first); Bayer, 205-207 (quoted second)

- ↑ Moulton, 534

- ↑ The Bridal Chamber of Herse, from a set of eight tapestries depicting the Story of Mercury and Herse, MMA

- ↑ Bayer, 205-206, with illustrations of the full set

- ↑ Jestaz; Pon, 149-150; Morka, 82

- ↑ Landau, 284-287; Bury, throughout, Kris, 3-4

- ↑ Morka, generally on early Polish medals, 82-83 on Caraglio.

- ↑ Morka, 82

- ↑ Landau, 286; Shultz and Mosca, 114; Jestaz

- ↑ Shultz and Mosca, 114 (this seems to have been the case; the legal situation is not well explained)

- ↑ Shultz and Mosca, 114; Pon, 150 (many later sources are also rather confused on the point)

- ↑ Bryan

- ↑ None listed in the bibliography in Jestaz, revised in 2004, nor by Pon

- ↑ "Bona Sforza (1493-1557), Queen of Poland, Cameo by Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio, MMA

- ↑ Kris, 4-5, all illustrated on p. 3

- ↑ Jestaz; see Morka for several medals and illustrations

- ↑ Jestaz and Shearman for sets, Bryan, 1886-9 for single prints

- ↑ Landau, 159; Jestaz; Shearman, 64, 67, 194-195 (rather contradicting each other)

- 1 2 Shearman, 67, 195

- ↑ Shearman, 195, n 34; Jacobson, 303-307;the Rosso drawing

- ↑ Landau, 285

References

- Bayer, Andrea, ed. Art and Love in Renaissance Italy, 2008, #101 and see index, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 1588393003, 9781588393005, Google books

- Bryan, Michael (1886). Robert Edmund Graves (ed.). Dictionary of Painters and Engravers, Biographical and Critical. Vol. I: A-K. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 230.

- Bury, Michael; The Print in Italy, 1550-1620, 2001, British Museum Press, ISBN 0714126292

- Jacobson, Karen, ed (often wrongly cat. as George Baselitz), The French Renaissance in Prints, 1994, Grunwald Center, UCLA, ISBN 0962816221

- Jestaz, Françoise, "Caraglio, Giovanni Jacopo." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed March 1, 2013, subscriber link

- Kris, Ernst, "Notes on Renaissance Cameos and Intaglios", Metropolitan Museum Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Dec., 1930), pp. 1-13, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, JSTOR

- Landau, David, and Parshall, Peter. The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0300068832

- Mayor, Hyatt A., Prints and People, Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton, 1971, ISBN 0691003262

- Morka, Mieczysław, "The Beginnings of Medallic Art in Poland during the Times of Zygmunt I and Bona Sforza", Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 29, No. 58 (2008), pp. 65-87, JSTOR

- Moulton, Ian Frederick, Review of Taking Positions: On the Erotic in Renaissance Culture by Bette Talvacchia, Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 52, No. 4 (Winter, 2001), pp. 532-535, Folger Shakespeare Library in association with George Washington University, JSTOR

- Pon, Lisa, Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi, Copying and the Italian Renaissance Print, 2004, Yale UP, ISBN 9780300096804

- Schulz, Anne M., Mosca, Giammaria, Giammaria Mosca Called Padovano: A Renaissance Sculptor in Italy and Poland, Vol 1, 1998, Penn State Press, ISBN 0271044519, 9780271044514, google books

- Shearman, John. Mannerism, 1967, Pelican, London, ISBN 0140208089

Further reading

- H. Zerner: ‘Sur Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio’, Actes du XXIIe Congrès international d’histoire de l’art: Budapest, 1969, pp. 691–5

- S. Boorsch, J. T. Spike and M. C. Archer: Italian Masters of the 16th Century (1985), 28 [XV/i] of The Illustrated Bartsch, ed. W. Strauss (New York, 1978–)

- B. Talvacchia: Taking Positions: On the Erotic in Renaissance Culture (Princeton, 1999)

- J. Wojciechowski: ‘Caraglio w Polsce’, Rocznik Historii Sztuki, xxv (2000), pp. 5–63

- J. Wojciechowski: ‘Caraglio’ [catalogue raisonné], self-publishing, 2001 [2017]