Giuliano de' Medici | |

|---|---|

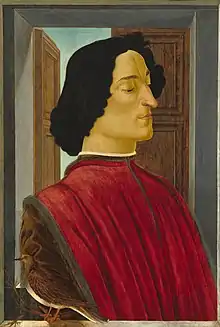

Portrait by Sandro Botticelli | |

| Full name | Giuliano di Piero de Medici |

| Born | 25 October 1453 Florence, Republic of Florence |

| Died | 26 April 1478 (aged 24) Florence Cathedral, Republic of Florence |

| Noble family | Medici |

| Issue | Giulio de' Medici, later Pope Clement VII (ill. by Fioretta Gorini) |

| Father | Piero the Gouty |

| Mother | Lucrezia Tornabuoni |

Giuliano de' Medici (28 October 1453 – 26 April 1478)[1] was the second son of Piero de' Medici (the Gouty) and Lucrezia Tornabuoni. As co-ruler of Florence, with his brother Lorenzo the Magnificent, he complemented his brother's image as the "patron of the arts" with his own image as the handsome, sporting "golden boy." He was killed in a plot known as the Pazzi conspiracy.

Personal life

In 1478, Giuliano was promised in marriage to Semiramide Appiani Aragona, daughter of Iacopo III Appiani, Prince of Piombino and niece of his presumed lover Simonetta Vespucci,[2] though died before the wedding could take place.[3] After Giuliano's death, Semiramide married his cousin, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici, in 1482.[3]

Giuliano had an illegitimate son by his mistress Fioretta Gorini,[4] Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici, who would later become Pope Clement VII.[5]

The Pazzi conspirators attempted to lure Giuliano and Lorenzo away from Florence to kill them outside the boundaries of the city – first on the road to Piombino, then in Rome,[6] and finally at a banquet hosted by the Medici at their villa in Fiesole. Giuliano did not come, claiming to be ill. The choice to commit the murder at high mass was a last minute choice.

Death

As the opening stroke of the Pazzi conspiracy, Giuliano was assassinated on 26 April 1478 – in the Duomo of Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, by Francesco de' Pazzi and Bernardo Baroncelli.[7] During Mass, at the sounding of the Elevation, he received a fatal sword wound to the head and was stabbed 19 times. He died lying on the cathedral floor.[8][9] Lorenzo, who had escaped to the Medici palace, did not learn of his brother's death for several hours.[10]

After a modest funeral on 30 April 1478,[3] Giuliano was buried in his father's tomb in the Church of San Lorenzo, but later, with his brother Lorenzo, was reinterred in the Medici Chapel of the same church, in a tomb surmounted by a statue of the Madonna and Child of Michelangelo.[8][12] After his death, at least two sonnets about Giuliano circulated in Florence, one of them written by Luigi Pulci for Lucrezia Tornabuoni the mother of Giuliano.[13]

Portrayals in media

Angelo Poliziano wrote two works which include Giuliano de' Medici as a major character. Stanze cominciate per la giostra del Magnifico Giuliano de’ Medici was written to commemorate a joust that Giuliano won in 1475.[14] It is mostly fictionalized and involves Giuliano's love for Simonetta Vespucci. It was left unfinished, for both of his protagonists (Giuliano and Simonetta) died. The other work is Coniurationis Commentarium, which was written in 1478 to commemorate Giuliano's murder. It explains the people involved in the plot and the events of the day of his assassination.[15]

Giuliano's portrait by Sandro Botticelli is thought to have been painted shortly after his death. The open window and dove were known symbols of death, and some have suggested that the lowered eyelids suggest that a death mask may have been used as reference.[16]

Giuliano makes a brief appearance in the video game Assassin's Creed II (2009) where he is murdered by Francesco de' Pazzi and other conspirators of the Pazzi conspiracy who were seeking to take over Florence under the command of Rodrigo Borgia, the future Pope Alexander VI.[17]

Giuliano is portrayed by Tom Bateman in Starz's original series Da Vinci's Demons (2013–2015).[18] He has an affair with Vanessa, who becomes pregnant with his child.[19] He is murdered in the season 1 finale.[20] Giuliano de' Medici was portrayed by Bradley James in the second season of the TV series Medici: Masters of Florence (2016–2019).[21]

Giuliano's murder is described in Jack Dann's 2019 novel Shadows in the Stone.[22]

References

- ↑ Cabrini, Anna Maria (2014). "Medici, Giuliano di Piero de'". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian).

- ↑ Jiminez, Jill Berk (15 October 2013). Dictionary of Artists' Models. Routledge. pp. 547–548. ISBN 978-1-135-95914-2.

- 1 2 3 Simonetta, Marcello (2008). The Montefeltro Conspiracy. United States: Doubleday. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-385-52468-1.

- ↑ Penny (12 September 2011). "The true son of the Devil, an Antichrist and abominable tyrant – or just unable to make up his mind?". Beyond the Yalla Dog. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ↑ Sannio, Simone (6 December 2016). "Inside the Medici Chapels, the "Masters of Florence"'s Mausoleum". L'Italo-Americano. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ↑ Unger, Miles J (2009). Magnifico : the brilliant life and violent times of Lorenzo De' Medici (1st Simon & Schuster trade pbk. ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0743254359.

- ↑ Smedley, Edward; James, Hugh James; Rose, Henry John (1845). Encyclopaedia Metropolitana; Or, Universal Dictionary of Knowledge on an Original Plan Comprising the Twofold Advantage of a Philosophical and an Alphabetical Arrangement, with Appropriate Engravings. B. Fellowes. p. 272.

- 1 2 Koestler-Grack, Rachel A. (1974). Joseph, Michael (ed.). Leonardo Da Vinci: Artist, Inventor, and Renaissance Man. Infobase Publishing. p. 152. ISBN 978-0791086261.

- ↑ Poliziano, Angelo (2012). Coniurationis Commentarium. Florence: Firenze University Press.

- ↑ Bernier, Olivier (1983). The Renaissance Princes. Chicago, IL: Stonehenge Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-86706-083-6.

- ↑ "Giuliano de' Medici". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ Barenboim, Peter; Shiyan, Sergey (2006). The Sacred Feminine and the Triads of Michelangelo and Botticelli. Moscow. ISBN 5-85050-825-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Balowski, Carl (2020). On the Death of Giuliano de Medici: An English translation of poetry from 1478.

- ↑ Aquilecchia, Giovanni; Oldcorn, Anthony. "The Renaissance". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ Poliziano, Angelo; Perini, Leandro (2012). Coniurationis Commentarium. Firenze University Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-88-6655-117-1.

- ↑ "Giuliano de' Medici". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ Castaño Ruiz, Clara (18 October 2015). "Assassin's Creed: 10 momentos históricos de la saga". Hobby Consolas (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ Terrace, Vincent (2017). Encyclopedia of Television Shows: A Comprehensive Supplement, 2011–2016. McFarland & Company. p. 45. ISBN 9781476671383.

- ↑ Houx, Damon (7 June 2013). "'Da Vinci's Demons' Season Finale Review: "The Lovers"". ScreenCrush. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ Carabott, Chris (1 June 2013). "Da Vinci's Demons: "The Hierophant" Review". IGN. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ Clarke, Stewart (10 August 2017). "Daniel Sharman and Bradley James Join Netflix's 'Medici'". Variety. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ↑ Dann, Jack (11 July 2019). Shadows in the Stone. IFWG. ISBN 9781925759792.

External links

![]() Media related to Giuliano de' Medici at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Giuliano de' Medici at Wikimedia Commons