The Globe of Gottorf is a 17th-century, large, walk-in globe of the Earth and the celestial sphere. It measures 3.1 meters in diameter. Conceived and constructed at Gottorf Castle near Schleswig, it was later transferred to the Kunstkamera museum in Saint Petersburg in Russia. Following a fire in 1747 most of the globe had to be reconstructed. A modern replica was constructed in 2005 at the original location near Schleswig.

The globe features a map of the Earth's surface on the outside and a map of star constellations with astronomical and mythological symbols on the inside. Turned manually or by water power, it demonstrates the movement of the heavens to those seated inside. It was a predecessor of the modern planetarium.

The globe was built between 1650 and 1664 on the request of Frederick III, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp. The construction was supervised by Frederick's court scholar and librarian Adam Olearius and carried out by the gunsmith Andreas Bösch from Limburg an der Lahn.

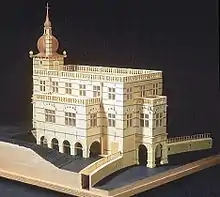

The Globe house in the Neuwerk Garden

The Globe probably already featured in early plans for the Neuwerk garden (the "new work") at Gottorf Castle, which was laid out from 1637. Not before 1650 did Duke Frederick embark on the construction of the garden's central point, the Globe house pavilion. The building was completed in seven years, while construction of the Globe itself took rather longer. Work came to a halt with the death of Duke Frederick III in 1659 in the Second Northern War.[1] The globe was eventually completed in 1664 by Frederick's son Christian Albrecht.[2]

The likely architect of the Globe house was Adam Olearius who was the court scholar and librarian at Gottorf. The orientation of the house was north–south, the location central at the lower end of the terraced Neuwerk garden. A semi-circular wall ran from the house to the Hercules pond in the South; the area between wall and pond contains the formal "Globe garden". The house was a symmetric, four-storey brick building with a terrace on the flat roof. There were extensions on all sides that reached to the second floor. The northern extension was a higher tower crowned with a copper onion dome.[1]

The building had two basement levels, above these the Globe hall and the upper floor with sleeping quarters and a hall facing south. These two upper floors and the roof terrace were connected by a spiral staircase in the tower. The main floor had the main entrance in the North and was level with the first garden terrace. The lower basement was level with the Globe garden to the South. Excluding the extensions or tower, the building measured a respectable 200 m2 in area and 14 m in height, perhaps giving rise to the occasional labelling as "Friedrichsburg" (Frederick's castle, in contrast to the palace that was Gottorf Castle). The official designation was "Lusthaus" (folly or hunting lodge); only toward the latter decades of its existence was it called "Globe house". The cubic shape and accessible flat roof were in keeping with contemporary counterparts in Italy, Netherlands and Denmark. The building was supposed to appear exotic and was occasionally called "Persian House". The building detail, however, adhered to the Northern Renaissance that was the norm at the time in the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein.[1]

Little is known about how the Globe house was used; excavations revealed evidence of extensive meals in the House. It seems to have been hardly used after the death of Duke Frederick III. Leaks in the flat roofs damaged the building, but the Globe remained a popular exhibition piece and was readily demonstrated to visitors.[1]

The Globe

The centrepiece of the Globe house was the large globe. On the outside it presented the Earth's surface, while its interior contained a planetarium that showed the celestial sphere with stars and constellations as well as the movement of the Sun as it appeared from the Earth. (The label "planetarium" may be disputed, as the device showed only the motion of the Sun, not of the Moon or planets.[3]) The particular attraction was to climb into the globe, sit down and allow the stars to circle around the Earth. The Globe was an invention of the Duke; the scientific lead lay with his court scholar and librarian Adam Olearius. The gunsmith Andreas Bösch was hired from Limburg an der Lahn to make the project a reality.[1]

Construction of the Globe and its building went hand in hand. Parts were made in a nearby forge and assembled in the Globe house. Seven to nine craftsmen worked on the project for several years.[1]

Simultaneously, between 1654 and 1657, Bösch worked on his own invention, the Sphaera Copernicana. At a time when work on the Globe had already made great progress, this enhanced and extended the cosmological concept of the Globe.[4]

Transfer to Saint Petersburg

_by_shakko_02.JPG.webp)

Slight controversy remains regarding the circumstances of the gifting of the Globe to Tsar Peter the Great in 1713.[2][1] In the Great Northern War, Gottorp was treading a fine line between Danish occupation and sympathies with Sweden. Duke Frederick IV had died in battle, his son Charles Frederick was under age, his uncle Christian August was regent. Early in 1713 Tsar Peter held conference with his ally, king Frederick IV of Denmark in Holstein, possibly Gottorf. Following the meeting, Peter solicited the Globe to be transferred to Russia. In July 1713, Christian August complied and ordered the Globe dispatched to Saint Petersburg where it arrived in 1717. Due to the ongoing war, the transport was apparently by sea to Pillau (a harbour near Königsberg), onward by land to Riga, by sea to Reval (Tallinn) and by land to Saint Petersburg. It became eventually part of the Kunstkamera in 1726, but the transport and elapsed time had left their mark on the condition of the Globe.[2]

The Globe suffered severe damage in a mysterious fire at the Kunstkamera in 1747. Only few of its metal parts, and none of the wood or canvas, survived the fire intact. The entrance hatch had been kept separately in the basement and so was unaffected by the fire. The Globe was removed from the Kunstkamera and reconstructed by Benjamin Scott from 1748 to 1750. However, the outer painting with contemporary geography proceeded slowly and was completed only in 1790 by Theodor von Schubert. A new pavilion had been constructed and the Globe moved there in 1753.[2]

In 1828 the Globe was transferred to the eastern rotunda of the Zoological Museum, and in 1901 to the Admiralty at Tsarskoje Selo, just south of Saint Petersburg.[2]

In 1941 German troops seized the Globe and it was taken by special train to Neustadt in Holstein where it was kept, fully packed and on its special rail carriage, presumably to await eventual transport to Gottorf Castle. In 1946 British troops took the Globe from Neustadt to nearby Lübeck, where it was on public display for three weeks. In 1947 the Globe was moved to Hamburg and shipped to Murmansk and onward to the Hermitage in Leningrad.[2]

It was decided to restore the Kunstkamera, to place the Globe in it and to restore it.[2]

At Gottorf in 1713, in order to retrieve the Globe from the Globe house in one piece, a large piece of the western facade had been removed. This sealed the fate of the building, which was also bereft of its main purpose. Only half-hearted maintenance was carried out from then on and the building decayed. In November 1768, after 50 years of disuse, King Christian VII of Denmark ordered the building to be auctioned off. After another year nothing remained of the ruins, and a building unique in the history of architecture and technology was lost.[1]

A visit to the original Globe house

Entry into the Globe house was from the North by the decorative portal of the main entrance, below the tower with the staircase. A short corridor led to the globe hall, which occupied almost the whole space of this level. The hall had numerous windows and was white in colour for best illumination of the Globe; the ceiling was stuccoed. The Globe itself stood in a wide, twelve-sided, wooden, horizontal ring, which was supported by an alternation of herm pillars and Corinthian columns. Painted on the exterior of the Globe was the then known world – Europe, Africa, America and Asia – with coloured country borders and with depictions of animals, ships and sea creatures. The cartography was based on globes from the famous cartographers Willem Blaeu and Joan Blaeu from Amsterdam.[5]

A small hatch permitted entry into the Globe to take a seat at the round table at the centre of the sphere. From here one could observe the celestial sphere depicted on the inside of the globe. The stars were represented by more than 1000 gilded brass nail heads, while the constellations were painted as coloured figures on the blue background of the heavens. The Globe included mechanisms to show the annual movement of the Sun and to drive a "world clock" that indicated where on Earth it was midday or midnight. The Globe was driven, either by water power from the basement to make one turn in 24 hours, or manually by the occupant of the Globe to accelerate the otherwise imperceptible motion. The Globe of Gottorf was the first planetarium where the observer could enter the interior. At the same time it is a large model of the old geocentric model after Ptolemy. When not in use, the hatch was closed with a cover that featured the Gottorf coat of arms; the Globe would then be covered in a heavy, green, woollen cloth. The doors of the Globe hall featured portraits of Nicolaus Copernicus and Tycho Brahe, in reverence to the foremost authorities of astronomy at the time.[5]

While the main floor with the Globe provided space for learned discussions among a larger audience, the upper level was more private with its sleeping quarters and a festive hall. French doors led onto the flat roofs of the extensions. The large roof terrace offered magnificent views of the gardens and invited to feasts under the open sky.[5]

Access to the two basement levels was separate, from the outside. The upper basement had a kitchen stove to cater for festive meals. The lower basement housed the water mill that was meant turn the Globe continuously. The force was transferred by a brass worm drive and long iron shafts.[5]

The technology

The Globe of Gottorf was principally of wrought iron construction. The sphere had a cage of 24 meridian rings executed as T-beams and an equator ring for stiffness. The cage was covered on the outside with copper sheet, followed by several layers of chalk and linen canvas with its outer layer polished. On this the cartography could be painted. The interior of the Globe was lined with thin pine board, also followed by chalk and linen canvas. The hatch was held in place by two spring locks; while the Globe was occupied the hatch remained removed.[6]

The sphere rotated around a heavy, fixed, wrought iron axis. At its foot end the axis rested on a millstone, at the top it was fixed to a ceiling beam. The axis was inclined at 54°30', the geographic latitude of Schleswig. This ensured the display of the night sky as it appeared over Schleswig, as was the purpose.[6]

The seating, apparently for up to ten or twelve persons, was mounted on the axis. It was constructed of heavy iron rails that were clamped to each other and fixed to the axis with heavy braces. This construction carried the narrow seat, the footrest and the round table at the centre. The backrest was a broad horizon ring made of brass, which displayed details of the Gregorian and Julian calendars, as well as astronomical data regarding the daily altitude of the Sun.[6]

The table at the centre supported a copper half globe. Following the cosmological concept of the Gottorf Globe, it symbolised the Earth as the centre of the celestial sphere. Due to the inclination of the globe axis, Gottorf lay at the top of the copper hemisphere and as such formed the centre of this artificial world. Around the table globe was a horizontal ring indicating the geographic longitude of various places on Earth. When the Globe moved, two opposite pointers would slide over this ring to indicate where on Earth it was midday or midnight.[6]

In line with contemporary taste, the celestial sphere was colourful and with elaborate figures for the constellations. Stars were represented by eight-pointed nail heads of gilded brass. These were grouped into the traditional six magnitudes to illustrate the actual brightness differences of the stars. Two candles on the table made the stars twinkle. Along the ecliptic, on the celestial sphere, moved a cog on which was mounted a model of the Sun made of cut crystal. This exhibited both the daily motion of sunrise and sunset and the annual movement, the seasonal change of rise and set points and of the Sun's maximum altitude. A meridian semicircle above the observer had a degree scale. It was not possible to display the complex movement of Moon or planets with the Globe.[6]

At its south pole the interior of the Globe has three transmissions. One of these, via long shafts, turned the "world clock" on the table. Second, an epicyclic gearing moved the Sun. The third transmission served the manual drive of the Globe, whereby the occupant could turn it with their fingertips. With this manual drive, one revolution took about 15 minutes and demonstrated all daily celestial movements as seen from Gottorf. The position of the Sun could be adjusted to demonstrate other seasons. Thus the Globe of Gottorf was the first walk-in planetarium in history, which gave the visitor a "live" demonstration of the phenomena of the heavens.[6]

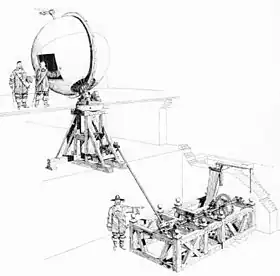

An alternative drive was a wooden watermill in the lower basement, which could turn the Globe in real time, at one revolution per day. A six-stage worm drive was used to slow the motion sufficiently. The mill was fed with water through lead pipes. In the basement the water fell onto the waterwheel and flowed away underground toward the Hercules pond. The heavy wheels and worms were made of brass and resulted in enormous friction losses. The motion was transferred two floors upward to the Globe by long, wrought iron shafts. The uppermost part of the transmission was at the foot of the Globe axis and was covered by a painted, wooden box. The watermill may have been more of a demonstration of technical aptitude than part of the scientific demonstration. 50 years after completion of the Globe house, the watermill drive had suffered significant decay.[6]

The Sphaera Copernicana

When the construction of the Globe reached its final stages, Andreas Bösch began a new project, the Sphaera Copernicana. This was to extend the concept of the Globe and its representation of Ptolemy's geocentric model, which was already recognised as antiquated by the Gottorf court. It seemed natural to create a demonstration model that showed the heliocentric model according to Copernicus, a "Sphaera Copernicana".[4]

While there were naturally parallels with the Globe in terms of construction and display, the Sphaera was more of an objet d'art than the Globe was. The Globe impressed with its size and original design, the Sphaera with a complex clockwork mechanism that controlled 24 different functions and displays simultaneously.[4]

Although Adam Olearius likely was involved in the construction, Bösch alone was responsible for the technical realisation of the project. In this he was again supported by a number of craftsmen, contributing the clockwork or designing the constellations. After completion the Sphaera Copernicana was placed in the Kunstkammer at Gottorf, later in the Gottorf library.[4]

When Gottorf Castle was cleared out in 1750, this Copernican armillary sphere was transferred to the royal Kunstkammer at Copenhagen. In 1824 it was to be decommissioned, but somehow in 1872 ended up in the Danish Museum of Natural History at Frederiksborg Castle, where it is still on display. The Sphaera Copernicana was recently restored, when missing parts were replaced and the original colour scheme re-established.[4]

The Sphaera Copernicana was considerably smaller than the Globe, with a diameter of 1.34 m and an overall height of 2.40 m. However, it was technologically much more advanced. It rested on a wooden base case that concealed a powerful spring-driven clockwork, which could run for eight days. Chimes occurred at hourly and quarter-hourly intervals, 24 motions in the armillary sphere were also driven by this device. The main drive shaft ran vertically from the centre of the clockwork through the whole armillary sphere. The shaft could be disengaged to drive the armillary sphere manually for demonstration purposes.[4]

At the centre of the armillary sphere a brass sphere represented the Sun. Surrounding it were brass rings supported on rollers, which represented the orbits of the then known planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn). The planets were represented by small silver figures that held their respective planet symbols in their hands. They revolved around the brass sphere at the same intervals as the real planets orbited the Sun. Sophisticated gearing ensured the correct transmission from the vertical drive shaft to the orbit ring. The position of each planet could be adjusted manually.[4]

Exceptionally, the Earth orbit carried not a silver figure, but a miniature armillary sphere with spheres for Earth and Moon. The Earth rotates daily around an axis inclined to point to the celestial pole. The Moon orbits Earth in 27.3 days and displays its phases. A small dial on the miniature armillary sphere displays the time of day.[4]

The planetary system was surrounded by two armillary spheres, of which the inner moved and the outer was fixed. Both consisted of six vertical semicircles and a horizontal ring. The inner sphere represented the "primum mobile", which at the time was the explanation for the precession of the equinoxes along the ecliptic. Two graduated bands of brass illustrated this movement, which took 26700 years for one revolution.[4]

The outer, fixed sphere carried the figures of the constellations and thus represented the celestial sphere. Today, 46 of originally 62 constellations remain. They were made of brass sheeting fixed to the inside of the rings of the sphere. Their interior was engraved and labelled with the Latin names of the constellations. The figures were evidently derived from a celestial globe of the Amsterdam cartographer Willem Blaeu. Small, six-rayed stars of silver were fixed to the inside of the brass sheeting. There were six different sizes of silver stars, corresponding to the six magnitudes used for stellar brightness.[4]

The manual drive consisted of a retractable shaft on which a crank could be placed. Similar to the Globe, this allowed to accelerate the movements of the Sphaera in order to make them visible and comprehensible.[4]

The entire device was crowned with a complex display of different times of day, plus the Sphaera Ptolemaica. The time of day display had three concentric, cylindrical walls that shifted against each other like curtains. A small solar disc, which changed height with the seasons, moved in front of the innermost cylinder. The position of the Sun relative to each curtain cylinder showed the time of day according to civil, Roman-Babylonian and Jewish convention, resp. The latter two of these conventions depend on the motion of the Sun, which is why astronomers since antiquity had been working with a day running from midnight to midnight. In the 16th and 17th century this was gradually adopted in civil life, also.[4]

Finally, the Ptolemaic armillary sphere on top of the time of day display, in assembly and movement, is a miniature version of the Globe. It has the Earth fixed at the centre with the celestial sphere surrounding it and revolving daily around it. The inside of the sphere has a solar figure moving around the ecliptic annually.[4]

Historical reconstruction at Gottorf

Thanks to the exceptional size and concept of the Globe, reports about it have been written ever since its construction and into the recent past. However, these did not result in a clear and precise idea of the real Globe at Gottorf; historical imagery was of little use in this context. Hence, knowledge about the Globe was restricted to knowledge about its builders, the epoch when it was constructed and more or less superficial descriptions of the Globe and Globe house. Where exactly in the House the Globe stood, or any other details of the building and technology were uncertain.[7]

The exception was an inventory of the Duke's residence drawn up in 1708 for general taxation purposes, which contained details about the value and condition of the buildings and gardens at Gottorf Castle. This included the Globe house in such detail as to fill the gaps of knowledge left by any illustrative material.[7]

Starting in 1991 with the text of the inventory, Felix Lühning prepared a reliable, drawing-based reconstruction of the Globe house. This included extensive archival research regarding the building and technological aspects of the Globe, such as invoices for building, repairs and maintenance of the Globe house. Excavation and survey of the Globe house foundations served to confirm these written sources.[7]

The Globe itself still existed with its principal parts at Saint Petersburg, allowing to measure the Globe and deduce more detail about the Globe house. Comparison with the Sphaera Copernicana at Frederiksborg Castle clarified matters further. The cartography had been lost, but the originals from which the Globe had been derived could be identified. It was then possible to undertake a reliable reconstruction of the Globe with regard to its construction, technological and astronomical content, and overall design.[7]

The result was, in 1997, a reconstruction by Felix Lühning of the Globe house in the Neuwerk garden in drawings and models, which were mainly based on the intense study of written sources. These certified the building materials to about 80%, the succession of rooms and distribution of space to 90%, the dimensions to 80%, and the appearance of the building to 50%. The excavations confirmed parts of the building to 100% certainty, while others, such as the portals, could be derived from contemporary comparisons to 90%. Some parts of the building could only be guessed at from contemporary buildings and typical methods of the time. The ground plan was 100% certain. More recent excavations by the State of Schleswig-Holstein, with more advanced means than available to Lühning, may necessitate a revision of the reconstruction of the basements, essentially by filling in previous gaps in knowledge.[7]

An exception was the watermill to drive the Globe. The cogwheels, worms and shafts were well documented from archival research, and their placement in the building had been described at the time. However, due to the unique character of the mechanism, Lühning had to leave 60% to his own conjecture.[7]

Globe and Neuwerk garden today

During the first decade of the 21st century, great efforts were undertaken to uncover the terrain of the Neuwerk garden, in order that the layout once again be visible. Scarce funding and the difficult terrain delayed this work significantly. Felix Lühning's work about the Globe triggered the eventual restoration of the baroque terrace garden. Garden, Globe and Globe house are vital features of Gottorf Castle that were never altered in any significant way. The restoration is, however not historically authentic. Rather, it is designed with aesthetic consideration in mind. Several charitable foundations supported the construction of the new Globe house and the reconstructed Globe. Both, along with the first part of the garden restoration, were inaugurated in May 2005.[8][9]

Since 2019, the state museums of Schleswig-Holstein offer a new exhibition in the Globe house, with information about the Globe, Globe house, baroque garden (Neuwerk garden) and early baroque horticulture. A virtual reality movie, featuring Adam Olearius and Duke Frederick III recounts the creation of the globe, placing it in the context of the Thirty Years' War.[10] Since 2020, extracts of the movie and further information about the Globe and Globe house are available in an online 360-degree application.[11]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Felix Lühning (2008). "Geschichte". Der Gottorfer Globus – ein barockes Welttheater (in German). Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 E.P. Karpeev (2003). Der Grosse Gottorfer Globus (in German). Hermitage, Saint Petersburg. ISBN 5-8843-1088-9.

- ↑ Susanne M. Hoffmann (2010-12-23). "Das "Weltwunder" von Gottorf – Der Gottorfer Globus als erstes Planetarium?". Spektrum (in German). Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Felix Lühning (2008). "Sphaera Copernicana". Der Gottorfer Globus – ein barockes Welttheater (in German). Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- 1 2 3 4 Felix Lühning (2008). "Rundgang". Der Gottorfer Globus – ein barockes Welttheater (in German). Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Felix Lühning (2008). "Technik I". Der Gottorfer Globus – ein barockes Welttheater (in German). Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Felix Lühning (2008). "Rekonstruktion". Der Gottorfer Globus – ein barockes Welttheater (in German). Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- ↑ "Schloss Gottorf: Ältestes Planetarium der Welt" (in German). Archived from the original on 2015-09-08. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- ↑ Schloss Gottorf: Der Gottorfer Globus (PDF) (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-09-27.

- ↑ "Neuer 360-Grad-Film: Wie die Idee zum Bau des Globus entstand" (in German). Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- ↑ "Virtueller Rundgang – Entdecken Sie den Gottorfer Globus und Barockgarten" (in German). Retrieved 2020-07-20.

Further reading

- Herwig Guratzsch, ed. (2005). Der neue Gottorfer Globus (in German). Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig. ISBN 3-7338-0328-0.

- Engel Petrovic Karpeev (2003). Bol'soj Gottorpskij globus (in Russian). Muzej Antropologii i Etnografii Imeni Petra Velikogo, Saint Petersburg. ISBN 5-88431-016-1.

- Felix Lühning (1997). Der Gottorfer Globus und das Globushaus im 'Newen Werck'. Katalogband IV der Sonderausstellung "Gottorf im Glanz des Barock" (in German). Schleswig.

- Felix Lühning (1991). "Das ganze Universum auf einen Blick – die Gottorfer Sphaera Copernicana von Andreas Bösch". Nordelbingen – Beiträge zur Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte (in German). Vol. 60. pp. 17–59. ISSN 0078-1037.

- Yann Rocher, ed. (2017). Globes. Architecture et science explorent le monde (in French). Norma éditions / Cité de l'architecture, Paris. pp. 42–45. ISBN 978-2-37666-010-1.

- Ernst Schlee (2002). Der Gottorfer Globus Herzog Friedrichs III (in German). Westholsteiner Verlagsanstalt, Heide. ISBN 3-8042-0524-0.

External links

- Gottorf Globe home page (in English).

- Saint Petersburg Kunstkammer page about the original globe (in English).

- Schloss Gottorf website (in English).

- Felix Lüning's website about the Gottorf original and replica globes (in German).

- Virtual tour of Globe, Globe house and Neuwerk garden (in German).