The Geatish Society (Götiska Förbundet, also Gothic Union, Gothic League) was created by a number of Swedish poets and authors in 1811, as a social club for literary studies among academics in Sweden,[1] with a view to raising the moral tone of society through contemplating Scandinavian antiquity. The society was formally dissolved in 1844, being dormant for more than 10 years.[2]

History

In the context of contentious debate over the suitability of Norse mythology as subjects of high art, in which the strong neoclassical training of northern academies, both Swedish and Danish, furnished powerful prejudices in favor of Biblical and Classical subjects, the members of the Götiska Förbundet sought to revive Viking spirit and related matters. When in 1800 the University of Copenhagen had made the debate the subject of a competition, the Danish Romantic Adam Gottlob Oehlenschläger expressed himself in favor of Norse mythology. Not only was it native, but because it had not become hackneyed and characteristically for the direction Northern European Romanticism nationalism was to take, because it was considered morally superior to Greek mythology. In 1817 Förbundet announced a competition for sculpture on Nordic themes.

The club published a magazine, Iduna, in which it printed a great deal of poetry, and expounded its views, particularly as regards the study of old Icelandic literature and history.[1] Swedish antiquarian Jakob Adlerbeth (1785–1844) was a leader in this organization and one of its most active members. He wrote several essays which were published in Iduna including translations of Edda and Vaulundurs saga.[3]

The members wrote extensively on the Æsir and other parts of Norse mythology. The historical writings of Olaus Rudbeck were also revived and used for creating vivid imagery. In their poems, especially the rich illustrations, actual Norse elements would be mixed with, for instance Nordic Bronze Age, Anglo-Saxon and Viking Era elements in order to create a modern mythology of the past.

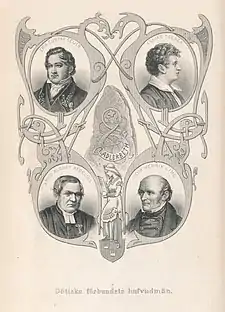

Among the most famous members were Esaias Tegnér and Erik Gustaf Geijer, both editors of Iduna. Some of their most famous poems were composed under the influence of the ideas and sentiments of the Geatish Society, notably the Frithiofs saga i form of epic verse and the shorter poem Skidbladner by Tegnér, as well as Geijer's poems Vikingen and Odalbonden. All were at least in part published in Iduna. Other well-known members were Arvid Afzelius, an editor of the ground-breaking anthology of Swedish folksong, Svenska visor från forntiden, the lyric poet Karl August Nicander, Swedish teacher Pehr Henrik Ling and Gustaf Vilhelm Gumaelius (1789–1877) author of the historical novel, Tord Bonde.

Members of the society would write extensively on the Vikings, often in a romanticized manner which described a largely heroic and noble ancient people. Members of the Geatish Society would occasionally wear horned helmets, which is the source of the myth that Vikings would have worn such helmets. In actuality, there is not evidence to suggest they ever did.

In 1844, following the death of Jakob Adlerbeth and the dissolution of the Society, part of the library accumulated by the Götiska förbundet, together with its archive, was given to the library of the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities (Vitterhetsakademiens bibliotek); there the materials are maintained among the special collections.[4]

The mythology and imagery of this movement was also very popular in the German Empire, where comparable societies were part of the "Völkisch movement". In the next century, similar themes would be taken up in Nazi Germany. To some extent they remain popular among Neo-Nazis to this day. Ideologically there seems no obvious connection, save the common concerns with sentimental patriotic interest in ethnic folklore, local history and a "back-to-the-land" anti-urbanism that are commonplaces of National Romanticism, employed as critiques of modern urban industrialism and its degenerative impact; however, Viking imagery alludes to conceptions of pristine Germanic tribes unaltered either culturally or racially by contact with non-Germanic tribes and cultures like Judaeo-Christianity. It thus provides an artistic ideal that was easily interpreted in terms of Nazi biological, cultural and political ideals. The idealized Vikings were associated with a warrior manliness that is transgressive of modern values; thus the imagery alludes to radical Nazi or pan-Germanic militarism.[5]

See also

References

- 1 2 Gosse, Edmund (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 505.

- ↑ Göthiska förbundet (Nordisk familjebok)

- ↑ Benson, Adolph Burnett (1914) The Old Norse element in Swedish romanticism (Columbia University Press)

- ↑ Special collections at Riksantikvarieaembetet Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Ahola, Joonas; Frog (2014). "Approaching the Viking Age in Finland". Fibula, Fabula, Fact: The Viking Age in Finland. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society. pp. 23–25. ISBN 978-952-222-603-7.

Sources

- This article is fully or partially based on material from Nordisk familjebok, Adlerbeth, 2. Jakob 1904–1926.

Other sources

- Molin, Torkel (2003) Den rätta tidens mått : Göthiska förbundet, fornforskningen och det antikvariska landskapet (Umeå Institutionen för historiska studier, Umeå univ)

- Hägg, Göran (2003) Svenskhetens historia (Wahlström & Widstrand)

- Algulin, Ingemar (1989) A History of Swedish Literature (Swedish Institute) ISBN 91-520-0239-X

- Tigerstedt, E.N. (1971) Svensk litteraturhistoria (Solna: Tryckindustri AB)