The Grant Memorial coinage are a gold dollar and silver half dollar struck by the United States Bureau of the Mint in 1922 in honor of the 100th anniversary of the birth of Ulysses S. Grant, a leading Union general during the American Civil War and later the 18th president of the United States. The two coins, identical in design and sculpted by Laura Gardin Fraser, portrayed Grant on the obverse and his birthplace in Ohio on the reverse.

The Ulysses S. Grant Centenary Memorial Association, also called the Grant Commission, wanted to sell 200,000 gold dollars to be able to finance multiple projects in the areas of Grant's birthplace and boyhood home. Congress authorized only 10,000 gold coins, but also authorized 250,000 half dollars. Hoping to boost sales, the Grant Commission asked for 5,000 of the gold dollars to bear a special mark, an incuse star; the Mint did the same for the half dollars as well, unasked for.

All the gold dollars and most of the half dollars were sold, although some half dollars were returned to the Mint for melting. The half dollar with star has long been priced higher than most commemoratives; its rarity has also caused it to be counterfeited. Money from the coins was used to help preserve Grant's birthplace, but other planned projects were not completed.

Background

Hiram Ulysses Grant was born at Point Pleasant, Ohio on April 27, 1822; his family moved to Georgetown, Ohio the following year.[1] His father was able to get him an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York in 1839; his name was entered as Ulysses S. Grant by mistake, and he chose to keep this name. Grant fought in the Mexican–American War. He resigned from the Army in 1854 and attempted several civilian trades with limited success. He was more successful once the Civil War began and he re-entered the military; after a series of victories, President Lincoln appointed him General in chief of Union Armies in late 1863. In April 1865, Grant effectively ended the war by capturing Richmond, Virginia and soon after forcing the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. In 1868, Grant was elected the 18th president of the United States, serving two terms.[2]

The Ulysses S. Grant Centenary Memorial Association was incorporated in 1921 to conduct the celebrations in Clermont County, Ohio, where Point Pleasant is. They sought to have a commemorative coin issued to help defray the costs.[3] In 1922, commemorative coins were not sold by the government—Congress, in authorizing legislation, usually designated an organization that had the exclusive right to purchase them at face value and vend them to the public at a premium.[4] In the case of the Grant Memorial coins, the responsible group was the Association, sometimes called the Grant Commission, of which Hugh L. Nichols was the chairman.[5]

Legislation

A bill for a Grant Memorial gold dollar to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his birth was introduced into the House of Representatives by Charles C. Kearns of Ohio on May 11, 1921. It called for the striking of 200,000 gold dollars to help finance community buildings as memorials to Grant in Georgetown and in Bethel, Ohio, and to help finance a road 5 miles (8.0 km) in length to be known as the General Grant Memorial Highway, leading from New Richmond, Ohio to Point Pleasant.[6] The bill was referred to the Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures.[6] On August 13, it was reported back to the House by the committee chairman, Albert Vestal of Indiana. The written report recommended a number of amendments—such as that the Grant Commission pay for the preparations for the coinage—and that the bill pass. It noted that Grant had lived in both Bethel and Georgetown, and there was at present only an impassible road between New Richmond and Point Pleasant. The report also said the Grant Commission had been established in May 1921, and that it was prepared to purchase all the coins and resell them through the hundreds of banks in Ohio eager to vend them. The profits would go to pay the cost of the centennial celebrations, to build the road, and if possible, to construct the community buildings.[7]

The bill was called up on the House's unanimous consent calendar on October 17, 1921. After the committee amendments were agreed to, Richard W. Parker of New Jersey had a number of questions, querying whether the bill's language meant that the Grant Commission would get the coins for free. He was told by Kearns that the government would be paid for the face value of the coins, and Thomas L. Blanton of Texas added that the U.S. government would charge no premium, but the Grant Commission could. Otis Wingo of Arkansas asked several questions in a colloquy with Kearns, resulting in the House being informed that since the gold coins would be struck from bullion already on hand, and as the bill obliged the Commission to pay for the coinage dies used, there would be no expense to the government. After this exchange, the bill passed without opposition.[8]

Upon reaching the Senate, the House-passed bill was referred to the Committee on Banking and Finance. That committee reported back through Connecticut's George P. McLean on January 23, 1922, reducing the number of gold dollars to 10,000 and authorizing 250,000 silver Grant Memorial half dollars.[9] The same day, McLean called up the bill before the Senate. Ohio's Frank Willis spoke in favor, explaining that the coins were to be used as a fundraiser by the Grant Commission, and that there would be no expense to the government. Reed Smoot of Utah noticed from the report that the entire bill—except the enacting clause—had been re-written, and questioned this; in response, Willis asked that the chairman of the Banking Committee, McLean, explain this. McLean said the House-passed bill had called for 200,000 gold dollars and the committee felt it unwise to tie up so much gold in a coin that would not circulate. This satisfied Smoot, after which the presiding officer, Vice President Calvin Coolidge, asked whether there was objection to the bill being considered. William H. King of Utah inquired whether the coin would set a bad precedent, and whether there would not be some expense involved; Willis assured him the Grant Commission would bear all costs, and that the proposal was similar to previous commemorative coin bills. Willis warned that if King objected to the bill, it would be postponed to such a degree as to defeat its purpose. Atlee Pomerene of Ohio took the floor to assure King of the importance of the bill to Ohio, and noted that the Commission was chaired by a former state chief justice, Nichols. Coolidge asked again whether there was any objection to the bill being considered; there being none, the Senate amended the bill as the committee had recommended, and passed the bill without objection.[10]

As the two chambers had passed different versions, the bill returned to the House of Representatives, where on January 26, Vestal brought the bill up for consideration. With no objection, the House agreed to the Senate amendments, passing the bill.[11] It became law with the signature of President Warren G. Harding on February 2, 1922.[12]

Preparation

-crop.jpg.webp)

The Commission of Fine Arts was charged by a 1921 executive order by President Harding with rendering advisory opinions on public artworks, including coins.[13] The passage of the Grant bill found most CFA members busy with other projects, and according to numismatic historian Don Taxay, the choosing of an artist to design the coin fell upon its sculptor-member, James Earle Fraser, designer of the Buffalo nickel. He selected his wife, Laura Gardin Fraser,[14] who had in 1921 designed the Alabama Centennial half dollar.[15]

On February 12, 1922, Laura Fraser wrote to the Director of the Mint, Raymond T. Baker, expressing her gratitude at being selected and stating that she was already at work and hoped to have the plaster models of the new coins in time for the next CFA meeting. She asked for assistance in obtaining an official letter of appointment to design the pieces, as she had experienced difficulty in getting paid for her work on the Alabama coin.[16] At the CFA meeting on February 24, members viewed the model for the obverse of the gold dollar and approved it. Laura Fraser completed her work soon thereafter.[17] On March 3, James Fraser wrote to CFA chairman Charles S. Moore, stating that he had inspected the models and gave his approval.[16] The full CFA ratified the decision in time for the production of gold coins to take place during March.[17]

Design

The designs for the two coins are identical except for the denomination. Laura Fraser worked from a photograph of Grant, by the studio of Mathew Brady, for the obverse; Taxay described Fraser's version as "remarkable for its strength and character".[17] On the coin, Grant wears a military coat, as he did during the Civil War, but the closely cropped beard suggests he is meant to look as he did in the years after the conflict.[18] Beneath the bust of Grant, facing right, is Fraser's initial G, for her birth last name, Gardin. Arlie L. Slabaugh, in his volume on commemorative coins, noted that Fraser had signed the Alabama coin LGF, and suggested that the single initial was to make less obvious the designer, lest there be charges of nepotism due to her husband's status as a CFA member.[19] Elsewhere on the obverse may be found Grant's name, the centennial dates, the denomination of the coin, and the issuing nation.[19]

The reverse depicts Grant's birthplace in Point Pleasant; Fraser again worked from a photograph, one showing the frame house before it was restored—the trees do not appear on the medal issued for the Grant birth centennial. The type of house was misidentified by Secretary of the Treasury Andrew W. Mellon in his annual report for 1922 as a log cabin, confusing it with one Grant built in his thirties on his wife's farm near St. Louis.[20] At the time of issue, Frank Duffield, editor of The Numismatist (the journal of the American Numismatic Association) stated that on the coin the house and its surroundings may be intended to look like they did when Grant was born, the building seems dwarfed by the trees, and "for the sake of better effect a little of the realism might have been sacrificed without detracting from historic interest".[21] He opined though that "in design and execution they are the equal of any of our recent commemorative issues, all of which have proved exceedingly popular with collectors."[21] Slabaugh stated of Laura Fraser's design, "there is no question of the fine quality of her work".[19] While the legends IN GOD WE TRUST and E PLURIBUS UNUM appear on the reverse, there is no inscription explaining what is pictured; as commemorative coin expert Anthony Swiatek explained, "the design itself tells the story".[22]

Art historian Cornelius Vermeule, in his volume on the U.S. Mint's coins and medals, admired Laura Fraser's design: "The only possible criticism, that the larger lettering is too large, fades when the curvatures of actual flans are studied. What seems potentially large and flat in photographs falls into harmonious beauty in actuality."[23] He stated of the obverse, "Grant is his gruff self, and in sum it can be said that a superlative beginning was made to the iconography of the Civil War in United States commemorative coinage.[24] Of the reverse, he noted, "Her trees, her little wooden house, and her rail fence are modeled and carved with a gem-cutter's precision. The texture of the leaves is one of the most subtle yet lively experiences on any surface of an American coin."[25]

Distribution and collecting

Both the Alabama and the Missouri Centennial half dollar (both 1921) had included a special mark on some of the issued coins, so that collectors would have to buy two coins for a complete set. The Grant Commission sought to do the same for its issues, and instructed the Mint to include a star on half (5,000) of the gold dollars.[26] The star was intended only for the dollar, and the inclusion of the star on some half dollars was "a bonus that greatly surprised the committee".[17] A letter from Philadelphia Mint Superintendent Freas Styer to the Director of the Mint dated March 14, 1922, confirms their telephone conversation that there were to be 5,000 of each denomination coined with a star.[27] As late as May 1922, The Numismatist printed that there was only one variety of half dollar.[18] The star had no relevance to the subject matter of the coin; its sole purpose was to sell more coins.[28] David Bullowa, in his 1938 work on commemoratives, suggested that had they used four stars, it would have denoted Grant's Civil War rank, but the single star was without apparent meaning.[29] In July 1922, Duffield wrote that there were two varieties of the half dollar, stating: "it is said that 5,000 of this variety were received unexpectedly by the committee, and that they are being sold at a higher price than the variety without the star."[30]

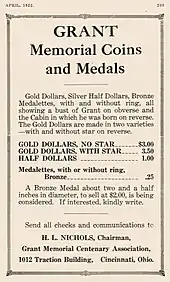

The Philadelphia Mint struck 5,006 half dollars with the star and 95,055 without. It also struck 5,016 gold dollars with the star and 5,000 without. All strikings took place in March 1922 with the excess coins over the even thousands reserved for inspection and testing at the 1923 meeting of the annual Assay Commission.[22] The star coins were struck first, and then the star was removed from the dies.[31] On April 15, Nichols wrote to the new Mint Director, Frank E. Scobey, stating that his commission had put the coins on sale, with the gold selling for $3.50 with star and $3 without, and the silver for $1.50 with star and $1 without. Because there were so many more silver coins than gold, the Commission had decided to require that banks and coin dealers buy 15 silver for every gold coin, a ratio lowered to 5:1 for individuals. Nichols offered to waive the requirement if Scobey wanted to buy some.[32]

In the December 1922 issue of The Numismatist, Nichols placed an advertisement warning that sales would close on January 1, 1923, and offering the no-star half dollar at $.75 each in lots of ten. The half dollar with star could be acquired for $1.50 and the gold dollar with star for $3.50. By then, there was no longer a requirement that silver pieces be purchased to obtain the gold.[33] The Grant Commission sold the entire issue of gold pieces, but returned 750 of the half dollars with stars and 27,650 of those without to the Mint for redemption and melting.[29] Few of the coins went to non-collectors; many of the half dollars and most of the gold pieces went to dealers and coin collectors.[34]

The Grant Commission also sought 150 of each denomination to be struck in proof condition; this was rejected by the Mint on the ground that it had not struck proof coins in several years.[32] Nevertheless, some proofs of each variety may exist; numismatist Anthony Swiatek estimates there may be four of each.[35]

Some of the Grant half dollars without stars were spent, and are worn from the effects of circulation. As the coins entered the secondary market, the half dollar with star especially appreciated in value; by 1935 it sold for $65, the highest value of any U.S. silver commemorative coin. In that year, a dentist from the Bronx, New York purchased several hundred of the half dollars without stars and proceeded to punch stars into them. Other counterfeiting has been done as well.[36]

By 1940, the half dollar without star sold for $1.50 and with star for $37; by 1950 $2.50 and $55, by 1970 $25 and $135.[37] The deluxe edition of R. S. Yeoman's A Guide Book of United States Coins (also known as the Red Book), published in 2018, lists the starred coins for between $900 and $9,750, and the ones without stars for between $110 and $1,000.[38] The gold dollars with stars sold for about $12 in 1940, with the ones without stars bringing $8. In 1950, these figures were $25 and $21 and in 1970, $265 and $250.[39] The Red Book lists the ones with stars for between $1,500 and $2,250, depending on condition, and the no-star pieces for between $1,200 and $2,500.[38]

Money from the coins was used to renovate Grant's birthplace, and to acquire land around it. President Harding spoke at the ceremony there.[40] In 1989, numismatist Ric Leichtung visited the municipalities where the money was to be used. He found Grant's birthplace in Point Pleasant and Grant's old schoolhouse in Georgetown. "There is no highway, no memorial buildings—just the two original structures moldering in Ohio's harsh winters and fierce summers."[41] The Red Book noted, "the buildings and highway never came to fruition".[42]

References

- ↑ Slabaugh, p. 52.

- ↑ Flynn, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Bullowa, p. 50.

- ↑ Slabaugh, pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Flynn, p. 94.

- 1 2 "H.R. 6119". May 11, 1921 – via ProQuest.(subscription required)

- ↑ House report, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ 1921 Congressional Record, Vol. 67, Page 6405 (October 17, 1921)

- ↑ Senate report, p. 1.

- ↑ 1922 Congressional Record, Vol. 68, Page 1557–1558 (January 23, 1922)

- ↑ 1922 Congressional Record, Vol. 68, Page 1773 (January 26, 1922)

- ↑ Swiatek & Breen, p. 88.

- ↑ Taxay, pp. v–vi.

- ↑ Taxay, pp. 59, 61.

- ↑ Bowers, pp. 639–640.

- 1 2 Flynn, p. 275.

- 1 2 3 4 Taxay, p. 61.

- 1 2 Duffield May 1922, p. 228.

- 1 2 3 Slabaugh, p. 50.

- ↑ Swiatek & Breen, p. 87.

- 1 2 Duffield May 1922, p. 229.

- 1 2 Swiatek, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Vermeule, p. 165.

- ↑ Vermeule, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Vermeule, p. 164.

- ↑ Bowers, p. 160.

- ↑ Flynn, pp. 94, 275.

- ↑ Slabaugh, p. 51.

- 1 2 Bullowa, p. 53.

- ↑ Duffield July 1922, p. 314.

- ↑ Swiatek, p. 135.

- 1 2 Flynn, p. 276.

- ↑ "Final sale of Grant Memorial coins (advertisement)". The Numismatist: 524. December 1922.

- ↑ Bowers, p. 161.

- ↑ Swiatek, p. 134.

- ↑ Swiatek & Breen, p. 89.

- ↑ Bowers, pp. 164–165.

- 1 2 Yeoman, p. 1061.

- ↑ Bowers, pp. 641–642.

- ↑ "Hugh L. Nichols (AKA Nicholas)". Supreme Court of Ohio. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ↑ Leichtung, pp. 1630–1632.

- ↑ Yeoman, p. 1060.

Sources

- Bowers, Q. David (1992). Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Wolfeboro, NH: Bowers and Merena Galleries, Inc. ISBN 978-0-943161-35-8.

- Bullowa, David M. (1938). "The Commemorative Coinage of the United States 1892–1938". Numismatic Notes and Monographs. New York, NY: American Numismatic Society (83): i–192. JSTOR 43607181. (subscription required)

- Duffield, Frank (uncredited) (May 1922). "Grant memorial coins being distributed". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 228–229.

- Duffield, Frank (uncredited) (July 1922). "Two varieties of the Grant half dollar". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 314.

- Flynn, Kevin (2008). The Authoritative Reference on Commemorative Coins 1892–1954. Roswell, GA: Kyle Vick. OCLC 711779330.

- Leichtung, Ric (October 1989). "Forgotten intentions". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 1630–1632. (subscription required)

- Slabaugh, Arlie R. (1975). United States Commemorative Coinage (second ed.). Racine, WI: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-307-09377-6.

- Swiatek, Anthony (2012). Encyclopedia of the Commemorative Coins of the United States. Chicago, IL: KWS Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9817736-7-4.

- Swiatek, Anthony; Breen, Walter (1981). The Encyclopedia of United States Silver & Gold Commemorative Coins, 1892 to 1954. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-04765-4.

- Taxay, Don (1967). An Illustrated History of U.S. Commemorative Coinage. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-01536-3.

- United States House of Representatives Committee on Coinage, Weights and Measures (August 13, 1921). Coinage of Gen. Grant gold dollar. United States Government Printing Office.

- United States Senate Committee on Banking and Currency (January 23, 1922). General Ulysses S. Grant memorial coin. United States Government Printing Office.

- Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

- Yeoman, R. S. (2018). A Guide Book of United States Coins (Mega Red 4th ed.). Atlanta, GA: Whitman Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-7948-4580-3.