| Grey-headed fish eagle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Icthyophaga |

| Species: | I. ichthyaetus |

| Binomial name | |

| Icthyophaga ichthyaetus (Horsfield, 1821) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The grey-headed fish eagle (Icthyophaga ichthyaetus) is a fish-eating bird of prey from South East Asia.[2] It is a large stocky raptor with adults having dark brown upper body, grey head and lighter underbelly and white legs.[3] Juveniles are paler with darker streaking. It is often confused with the lesser fish eagle (Icthyophaga humilis) and the Pallas's fish eagle. The lesser fish eagle is similar in plumage but smaller and the Pallas's fish eagle shares the same habitat and feeding behaviour but is larger with longer wings and darker underparts. Is often called tank eagle in Sri Lanka due to its fondness for irrigation tanks.[4]

Taxonomy

The grey-headed fish eagle is included in the order Accipitriformes and the family Accipitridae, which includes most birds of prey except for the ospreys and falcons.[4] Lerner & Mindell placed the grey-headed fish eagle in the subfamily Haliaeetinae, which includes the genera Haliaeetus (sea eagles)[5] It was first described by Horsfield in 1841 as Falco ichthyaetus.[6] This paraphyletic group forms a close sister relationship with the subfamily Milvinae (composed of two genera, Milvus and Haliatur), based on the shared trait of basal fusion of the second and third phalanges found only in these two groups.[7] Some taxonomic authorities place this species in the monotypic genus Ichthyophaga.

Description

A smallish to medium-sized but quite bulky fish eagle. Has a small bill, a small head on long neck, rounded tail and shortish legs with unfeathered tarsi and long talons. Wings aren't very long and wingtips reach less than halfway down tail. Males and females are sexually dimorphic. The grey-headed fish eagle has a body length of 61–75 cm.[6] Females are heavier than males at 2.3–2.7 kg compared to 1.6 kg.[4] The tail measures between 23–28 cm and the tarsus 8.5–10 cm.[4] The wingspan measure between 155–170 cm.[6]

Adults are grey-brown with a pale grey head and pale iris, belly and tail are white with the having a broad black subterminal band.[3] Breast and neck are brown, with the wings on top dark brown with blacker primaries and below brown.[4] Juveniles the head and neck are brown, greyer on the ides of throat, with buff supercilia and whitish streaks.[4] The rest of the upperparts are darker brown, edged with grey and secondaries and tertials faintly barred.[3][4] Tail black and white marbled with broader dark subterminal band and white tip.[3] Belly and thighs white, while breast and flanks brown streaked with white.[4] Iris is darker than adult.[3] As juveniles mature subterminal band becomes more prominent, head becomes greyer and loses streaking becoming uniformly brown.[4]

Distribution and habitat

The grey-headed fish eagle has a wide distribution (38˚ N to 6˚ S) that encompasses India and South-East Asia to Malaysia, Western Indonesia and Philippines.[4] It is generally uncommon but can be rare or local. In North and East India it is found in Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Assam.[4] It is uncommon in North and East Sri Lanka,[4] rare and local in Nepal and uncommon and local in Bangladesh.[3] It is rare and local in South Thailand and rare in Laos;[4] scarce in Vietnam, Cambodia and Malaysia to Sumatra;[8][9][10] very rare in Java and Sulawesi except for a small local population and scarce in Borneo and the Philippines.[4][11]

Habitat

Grey-headed fish eagles live in lowland forest up to 1,500 m above sea-level.[4] Their nests are close to bodies of water such as slow-moving rivers and streams, lakes, lagoons, reservoirs, marshes, swamps and coastal lagoons and estuaries.[4][9] They are also known to frequent irrigation tanks in Sri Lanka, hence where their alternate English in Sri Lanka comes from.[3]

Ecology and behaviour

It is a sedentary bird that can be solitary or occur in pairs. It is non-migratory. Juveniles disperse from the breeding areas, presumably in search of mates or another food source. The grey headed fish eagle spends much of its time perching upright on bare branches over water bodies, occasionally flying down to catch fish.[4] Flight is heavy looking with sharp and full wing-beats on flattish wings.[4] Spends little time in the air soaring possibly due to habitat it lives in and no other aerial displays have been described.

Breeding

The breeding season of the grey-headed fish eagle usually takes place between November and May across most of its mainland range, but changes from December to March in Sri Lanka, November to January in India.[4] Nests have been found in January–March in Burma, April in Sumatra and August in Borneo, it is unclear whether these nest were old or being used for breeding.[6] Breeding in the protected Prek Toal area of the Tonlé Sap follow the flood regimes that begin in September, with eggs near hatching or hatching at peak flood waters in October–November.[9]

The grey-headed fish eagle builds a huge stick nest, up to 1.5 metres across and, with repeated use, up to 2 metres deep.[4] The nest is lined with green leaves and were situated in tall trees (8–30 m) on or near the top of the tree with an open crown structure, which can be in a forest or a standalone tree.[4][10] Nest sites were always near or by a water source with the avoidance of human habitations and is consistent with other fish eagles due to ease of access and food abundance.[10]

The clutch size can be between 2 and 4 eggs but usually 2 unmarked white eggs are laid per couple.[4] Little is known about the level of parental care employed by the grey headed fish eagle, the evidence points towards monogamy and shared parental care duties. Both incubation, foraging and fledgling feeding are carried out by the male and female, with incubation lasting 45–50 days and the fledgling period 70 days.[4][10]

Foraging and diet

As the common name suggests the grey-headed fish eagle is a specialist piscivore, which preys upon live fish and scavenges dead fish[9] and occasionally reptiles and terrestrial birds and small mammals.[4] Tingay et al.[9] found that the diet of the grey-headed fish eagle in the Prek Toal protected area of the Tonlé Sap contains the endangered Tonlé Sap water snake. Whether this is the primary prey item of their diet or a seasonal occurrence in this are remains unclear. The most common method of foraging used is to catch fish from a hunting perch close to a water source with a short flight to snatch prey on the water surface or just below.[6] Also quarters over stretches of river or lakes and fish too heavy to lift may be dragged to bank to devour.[4] It is also dynamic in prey pursuit and can catch fish in rough water such as rapids.[3] Both species in the genus Ichthyophaga have strongly recurved talons like the osprey (Pandionidae) a specialisation for catching fish, which is lacking in the genus Haliaeetus (sea eagles).[12]

Voice

The calls of the grey-headed fish eagle include a gurgling awh-awhr and chee-warr repeated 5–6 times, an owlish ooo-wok, ooo-wok, ooo-wok, a nasally honking uh-wuk and a loud high pitched scream.[3][4] These begin as subdued low short notes each succeeding one more strongly upturned and more strident then previous then dying away again and are uttered from a perch or on the wing.[3][4] Fledglings give a longer nasal uuuw-whaar that starts low and subdued then becomes, louder and higher and strident.[3] During the breeding season becomes quite vocal, with calls being loud and far carrying, often calling also at night.[4]

Threats

Although not currently considered to be threatened with extinction, the population of grey-headed fish eagles is declining, the result of numerous and varied threats. The loss of suitable wetland habitat, deforestation, over-fishing, siltation, persecution, human disturbance and pollution resulting in a loss of nesting sites and reduced food supply.[1][4] Tingay et al.[9][10] noted that these statements are based mostly on anecdotal evidence, although their studies found a definitive negative link between human habitation and grey-headed fish eagle nest occupancy rates in Cambodia. Another critical threat to the Cambodian populations of the grey-headed fish eagle on the Tonlé Sap is the damming of the Mekong River for hydropower, which will possibly have adverse effects on critical flood regimes of the Tonlé Sap.[9][10]

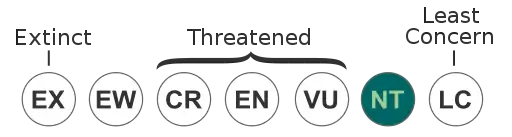

Conservation status

The grey-headed fish eagle is currently listed as Near-Threatened on the IUCN Red List.[1] The population is estimated to be between 10,000–100,000 mature individuals on the basis that it may not exceed a five figure total.[1] This estimate was completed in 2001 with poor data quality, combined with a marked decrease in populations is would be reasonable to assume that the number is closer to 10,000 and bordering on being classified Vulnerable.[1] The population is spread out over 5 million km² and is now thought be only common locally, with moderate rapid population decline throughout its range.[1]

Although there are no active conservation measures currently in place for the grey-headed fish eagle, there is an annual monitoring programme for the breeding population in the Prek Toal protected area at the Tonlé Sap Lake in Cambodia, which has been conducted each year since 2006.[9] The programme provides baseline information on the ecology of the species and the status and distribution of the breeding population.[10] A number of other conservation actions have also been proposed by the IUCN, these include surveys to reveal important areas and regularly monitor at various sites throughout its range, protect forest in areas known to be important to the species and conduct awareness campaigns involving local residents to engender pride in the species and encourage better care of wetland areas.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 BirdLife International (2016) [amended version of 2017 assessment]. "Ichthyophaga ichthyaetus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22695163A116996769. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ↑ Robson, C. (2000). A Field Guide to the Birds of South-East Asia. UK: New Holland Publishers.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Rasmussen, P. C.; Anderton, J. C. (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Vol. 1–2. Washington D.C. and Barcelona: Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Ferguson-Lees, J.; Christie, D. A. (2001). Raptors of the World. London, UK: Christopher Helm.

- ↑ Lerner, H. R. L.; Mindell, D. P. (2005). "Phylogeny of eagles, Old World vultures, and other Accipitridae based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 37 (2): 327–346. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.010. PMID 15925523.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thiollay, J. M. (1994). "Family Accipitridae (Hawks and Eagles)", pp. 52–205 in J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott & J. Sargatal (Eds.) Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 2. New World Vultures to Guineafowl. Vol. 2 . Barcelona: Lynx Ediciones.

- ↑ Lerner, H. R. L. (2007). Molecular phylogenetics of diurnal birds of prey in the avian Accipitridae family. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- ↑ Thiollay, J. M. (1998). "Distribution patterns and insular biogeography of South Asian raptor communities". Journal of Biogeography. 25: 52–72. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.1998.251164.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tingay, R. E.; Nicoll, M. A. C.; Visal, S. (2006). "Status and Distribution of the Grey-Headed Fish-Eagle (Ichthyophaga ichthyaetus) in the Prek Toal Core Area of Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia". Journal of Raptor Research. 40 (4): 277. doi:10.3356/0892-1016(2006)40[277:SADOTG]2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tingay, R. E.; Nicoll, M. A. C.; Whitfield, D. P.; Visal, S.; McLeod, D. R. A. (2010). "Nesting Ecology of the Grey-Headed Fish-Eagle at Prek Toal, Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia". Journal of Raptor Research. 44 (3): 165. doi:10.3356/jrr-09-04.1. S2CID 84491625.

- ↑ Thiollay, J. M.; Rahman, Z. (2002). "The raptor community of Central Sulawesi: Habitat selection and conservation status". Biological Conservation. 107: 111–122. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00051-4.

- ↑ Poole, A. F. (1989). Ospreys: A natural and unnatural history. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

.jpg.webp)