| Greenlandic Norse | |

|---|---|

| Region | Greenland; Western Settlement and Eastern Settlement |

| Ethnicity | Greenlandic Norse people |

| Extinct | by the late 15th century or the early 16th century |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Younger Futhark | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | non-GL |

| Part of a series on the |

| Norse exploration of North America |

|---|

|

Greenlandic Norse is an extinct North Germanic language that was spoken in the Norse settlements of Greenland until their demise in the late 15th century. The language is primarily attested by runic inscriptions found in Greenland. The limited inscriptional evidence shows some innovations, including the use of initial t for þ, but also the conservation of certain features that changed in other Norse languages. Some runic features are regarded as characteristically Greenlandic, and when they are sporadically found outside of Greenland, they may suggest travelling Greenlanders.

Non-runic evidence on the Greenlandic language is scarce and uncertain. A document issued in Greenland in 1409 is preserved in an Icelandic copy and may be a witness to some Greenlandic linguistic traits. The poem Atlamál is credited as Greenlandic in the Codex Regius, but the preserved text reflects Icelandic scribal conventions, and it is not certain that the poem was composed in Greenland. Finally, Greenlandic Norse is believed to have been in language contact with Greenlandic and to have left loanwords in it.

Runic evidence

Some 80 runic inscriptions have been found in Greenland. Many of them are difficult to date and not all of them were necessarily carved by Greenlanders.[2] It is difficult to identify specifically Greenlandic linguistic features in the limited runic material. Nevertheless, there are inscriptions showing the use of t for historical þ in words such as torir rather than þorir and tana rather than þana. This linguistic innovation has parallels in West Norwegian in the late medieval period.[2] On the other hand, Greenlandic appears to have retained some features which changed in other types of Scandinavian. This includes initial hl and hr, otherwise only preserved in Icelandic, and the long vowel œ (oe ligature), which merged with æ (ae ligature) in Icelandic but was preserved in Norwegian and Faroese.[3]

Certain runic forms have been seen by scholars as characteristically Greenlandic, including in particular an 'r' form with two parallel sloping branches which is found in 14 Greenlandic inscriptions.[4] This form is sporadically found outside Greenland. It is, for example, found in a runic inscription discovered in Orphir in Orkney, which has been taken to imply that "the rune carver probably was a Greenlander".[5]

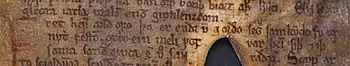

The Kingittorsuaq Runestone has one of the longest Norse inscriptions found in Greenland. It was discovered near Upernavik, far north of the Norse settlements. It was presumably carved by Norse explorers. Like most Greenlandic inscriptions, it is traditionally dated to c. 1300. However, Marie Stoklund has called for reconsideration of the dating of the Greenlandic material and points out that some of the parallels to the Kingittorsuaq inscription elsewhere in the Nordic world have been dated to c. 1200.[6]

| Transcription | English translation | |

|

|

The patronymic Tortarson (standardized Old Norse: Þórðarson) shows the change from þ to t while the word hloþu (Old Icelandic hlóðu, Old Norwegian lóðu) shows the retention of initial hl.

Manuscript evidence

A document written at Garðar in Greenland in 1409 is preserved in an Icelandic transcription from 1625. The transcription was attested by bishop Oddur Einarsson and is considered reliable. The document is a marriage certificate issued by two priests based in Greenland, attesting the banns of marriage for two Icelanders who had been blown off course to Greenland, Þorsteinn Ólafsson and Sigríður Björnsdóttir. The language of the document is clearly not Icelandic and cannot without reservation be classified as Norwegian. It may have been produced by Norwegian-educated clergy who had been influenced by Greenlandic.[8] The document contains orthographic traits which are consistent with the runic linguistic evidence. This includes the prepositional form þil for the older til which demonstrates the merger of initial 'þ' and 't'.[9]

It is possible that some other texts preserved in Icelandic manuscripts might be of Greenlandic origins. In particular, the poem Atlamál is referred to as Greenlandic (Atlamál in grœnlenzku) in the Codex Regius. Many scholars have understood the reference to mean that the poem was composed by a Greenlander and various elements of the poem's text have been taken to support Greenlandic provenance. Ursula Dronke commented that "There is a rawness about the language ... that could reflect the conditions of an isolated society distant from the courts of kings and such refinements of manners and speech as were associated with them."[12]

Finnur Jónsson argued that not only was Atlamál composed in Greenland, some other preserved Eddic poems were as well. He adduced various stylistic arguments in favor of Greenlandic provenance for Helgakviða Hundingsbana I, Oddrúnargrátr, Guðrúnarhvöt, Sigurðarkviða in skamma and, more speculatively, Helreið Brynhildar.[13] One linguistic trait which Finnur regarded as specifically Greenlandic was initial 'hn' in the word Hniflungr, found in Atlamál, Helgakviða Hundingsbana I and Guðrúnarhvöt. The word is otherwise preserved as Niflungr in Icelandic sources.[14] Modern scholarship is doubtful of using Atlamál as a source on the Greenlandic language since its Greenlandic origin is not certain, it is difficult to date, and the preserved text reflects Icelandic scribal conventions.[15][16]

Contact with Kalaallisut

Greenlandic Norse is believed to have been in language contact with Kalaallisut, the language of the Kalaallit, and to have left loanwords in that language. In particular, the Greenlandic word Kalaaleq (older Karaaleq), meaning Greenlander, is believed to be derived from the word Skrælingr, the Norse term for the people they encountered in North America.[17] In the Greenlandic dictionary of 1750, Hans Egede states that Karálek is what the "old Christians" called the Greenlanders and that they use the word only with foreigners and not when speaking among themselves.[18][19] Other words which may be of Norse origin include Kuuna (female given name, probably from Old Norse kona "woman", "wife"),[20] sava ("sheep", Old Norse sauðr), nisa ("porpoise", Old Norse hnísa), puuluki ("pig", Old Norse purka "sow"), musaq ("carrot", Old Norse mura) and kuaneq ("angelica", Old Norse hvönn, plural hvannir).[21][22]

The available evidence does not establish the presence of language attrition; the Norse language most likely disappeared with the ethnic group that spoke it.[2]

See also

| Part of a series on |

| Old Norse |

|---|

|

| WikiProject Norse history and culture |

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (24 May 2022). "Older Runic". Glottolog. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Archived from the original on 13 November 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 Hagland, p. 1234.

- ↑ Barnes 2005, p. 185.

- ↑ Stoklund, p. 535.

- ↑ Liestøl, p. 236.

- ↑ Stoklund, p. 534.

- ↑ The Rundata database, downloaded and accessed on 12 January 2008.

- ↑ Olsen, pp. 236–237.

- ↑ Olsen, p. 245.

- ↑ Bugge, p. 291.

- ↑ Hollander, p. 293.

- ↑ Dronke, p. 108.

- ↑ Finnur Jónsson, p. 66–72.

- ↑ Finnur Jónsson, p. 71.

- ↑ von See et al., pp. 387–390.

- ↑ Barnes 2002, pp. 1054–1055.

- ↑ Jahr, p. 233.

- ↑ Ita vocatus se dictitant à priscis Christianis, terræ hujus qvondam incolis. Nostro ævo usurpatur duntaxat ab Advenis, Grœnlandiam invisentibus, ab indigenis non item. Egede 1750, p. 68.

- ↑ Thalbitzer, p. 36.

- ↑ "girls name Kuuna – Oqaasileriffik". Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ↑ Jahr, p. 231.

- ↑ Thalbitzer, pp. 35-36.

Works cited

- Barnes, Michael (2002). "History and development of Old Nordic outside the Scandinavia of today". In The Nordic Languages: An International Handbook of the History of the North Germanic Languages: Volume 1. ISBN 3110148765

- Barnes, Michael (2005). "Language" in A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture, ed. by Rory McTurk. ISBN 0-631-23502-7.

- Bugge, Sophus (1867). Norrœn fornkvæði. Islandsk samling af folkelige oldtidsdigte om nordens guder og heroer almindelig kaldet Sæmundar Edda hins fróða.

- Dronke, Ursula (1969). The Poetic Edda I. ISBN 0198114974

- Egede, Hans (1750). Dictionarium grönlandico-danico-latinum.

- Finnur Jónsson (1894). Den oldnorske og oldislandske litteraturs historie.

- Hagland, Jan Ragnar (2002). "Language loss and destandardization in the Late Middle Ages and Early Modern Times". In The Nordic Languages : An International Handbook of the History of the North Germanic Languages : Volume 2, pp. 1233–1237. ISBN 311017149X.

- Hollander, Lee M. (1962). The Poetic Edda. ISBN 0292764995

- Jahr, Ernst Håkon and Ingvild Broch (1996). Language Contact in the Arctic: Northern Pidgins and Contact Languages. ISBN 3110143356.

- Liestøl, Aslak (1984). "Runes" in The Northern and Western Isles in the Viking World. Survival, Continuity and Change, pp. 224–238. ISBN 0859761010.

- Olsen, Magnus. "Kingigtórsoak-stenen og sproget i de grønlandske runeinnskrifter". Norsk tidsskrift for sprogvidenskap 1932, pp. 189–257.

- Rundata database.

- von See, Klaus, Beatrice la Farge, Simone Horst and Katja Schulz (2012). Kommentar zu den Liedern der Edda 7. ISBN 9783825359973

- Stoklund, Marie (1993). "Greenland runes. Isolation or cultural contact?" in The Viking Age in Caithness, Orkney and the North Atlantic, pp. 528–543. ISBN 0748606327

- Thalbitzer, William (1904). A Phonetical Study of the Eskimo Language.