| Classification | Sexual identity |

|---|---|

| Other terms | |

| Associated terms | Demisexuality |

| Flag | |

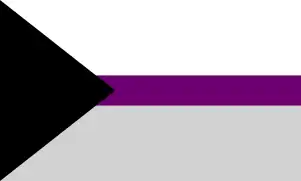

Graysexual pride flag | |

| Flag name | Graysexual pride flag |

| Sexual orientation |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Sexual orientations |

| Related terms |

| Research |

| Animals |

| Related topics |

|

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Asexuality topics |

|---|

| Related topics |

| In society |

| Studies |

| Attitudes and discrimination |

| Asexual community |

| Lists |

| Portals |

Gray asexuality, grey asexuality, or gray-sexuality is the spectrum between asexuality and allosexuality.[1][2][3] Individuals who identify with gray asexuality are referred to as being gray-A, gray ace, and make up what is referred to as the "ace umbrella".[4][5] Within this spectrum are terms such as demisexual, semisexual, asexual-ish and sexual-ish.[6]

The emergence of online communities, such as the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN), has given gray aces locations to discuss their orientation.[7]

Definitions

General

Gray asexuality is considered the gray area between asexuality and allosexuality, in which a person may only experience sexual attraction on occasion.[1][2] The term demisexuality was coined in 2006 by Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN).[4] The prefix demi- derives from the Vulgar Latin *dimedius, which comes from Latin dimidius, meaning "divided into two equal parts, halved."[8][9][10] The term demisexual comes from the concept being described as being "halfway between" sexual and asexual.

The term gray-A covers a range of identities under the asexuality umbrella, or on the asexual spectrum, including demisexuality.[11] Other terms within this spectrum include semisexual, asexual-ish and sexual-ish.[6] The gray-A spectrum usually includes individuals who very rarely experience sexual attraction; they experience it only under specific circumstances.[2][12] Sari Locker, a sexuality educator at Teachers College of Columbia University, argued during a Mic interview that gray-asexuals "feel they are within the gray area between asexuality and more typical sexual interest".[13] A gray-A-identifying individual may have any romantic orientation, because sexual and romantic identities are not necessarily linked.[4][6]

A gray-asexual may engage in sex with someone they have a strong connection to, but their relationship is not based on sex, nor do they crave sex.[4][14] This can also be known as gray areas, which can be combined with different orientations, such as:[15]

- A graysexual alloromantic person: rarely sexually attracted to others.

- An asexual grayromantic person: not sexually attracted to anyone, but does experience being romantically attracted to others on rare occasions.

- A gray-pansexual aromantic person: rarely attracted to people sexually of all genders, but never romantically attracted to anyone.

- A gynesexual gray-biromantic person: usually sexually attracted to women or feminine-presenting people; rarely experience romantic attraction towards more than one gender.

Aspec is a term which can be used to mean that one is on the asexual spectrum or aromantic spectrum.[16][17]

Demisexuality

A demisexual person does not experience sexual attraction until they have formed a strong emotional connection with a prospective partner.[2][7] The definition of "emotional bond" varies from person to person in as much as the elements of the split attraction model can vary.[18][19] Demisexuals can have any romantic orientation.[20][21] People in the asexual spectrum communities often switch labels throughout their lives, and fluidity in orientation and identity is a common attitude.[4]

Demisexuality, as a component of the asexuality spectrum, is included in queer activist communities such as GLAAD and The Trevor Project, and itself has finer divisions.[22][23]

Demisexuality is a common theme (or trope) in romantic novels that has been termed 'compulsory demisexuality'.[24] Within fictitious prose, the paradigm of sex being only truly pleasurable when the partners are in love is a trait stereotypically more commonly associated with female characters. The intimacy of the connection also allows for an exclusivity to take place.[21][25]

Post-doctorate research on the subject has been done since at least 2013, and podcasts and social media have also raised public awareness of the sexual orientation.[26] Some public figures, such as Michaela Kennedy-Cuomo, who have come out as demisexual have also raised awareness, though they typically face some degree of ridicule for their sexuality.[27] The word gained entry to the Oxford English Dictionary in March 2022, with its earliest usage (as a noun) dating to 2006.[28]

Fictosexuality

Fictosexuality refers to the sexual attraction towards fictional characters, encompassing those who lack attraction to real individuals and fall within the spectrum of gray asexuality.[29][30] These individuals can be found within online asexual communities.[29][30] In recent times, certain fictosexuals have actively participated in queer activism.[31]

Community

Online communities, such as the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN), as well as blogging websites such as Tumblr, have provided ways for gray-As to find acceptance in their communities.[7][12] While gray-As are noted to have variety in the experiences of sexual attraction, individuals in the community share their identification within the spectrum.[34]

In society, there is a lack of understanding of who asexuals are. They often limit their interactions to an online platform. Asexuals have also found it safer to communicate through the use of symbols and slang. Asexuals are often referred to as aces. People are often under the misconception that asexuals hate sex or never have sex. For them, sex is not a focal point. This is where the term gray-asexual comes in.[14][4]

A black, gray, white, and purple flag is commonly used to display pride in the asexual community. The gray bar represents the area of gray sexuality within the community,[14] and the flag is also used by those who identify as gray-asexual:[35]

- The black stripe represents asexuality as a whole.

- The gray stripe is for asexuals who fall anywhere within the asexual spectrum, including gray-asexual and demi-sexual identities.

- The white stripe represents allies of asexuality, including the non-asexual partners of some asexual people.

- The purple represents the asexual community.

Research

A 2019 survey by The Ace Community Survey reported that 10.9% asexual identified as gray-sexual and 9% identified as demisexual,[36] though asexuality in general is relatively new to academic research and public discourse.[7]

References

- 1 2 Bogaert, Anthony F. (January 4, 2015). Understanding Asexuality. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4422-0100-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Decker JS (2015). "Grayromanticism". The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction to Asexuality. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1510700642. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ↑ Julie Sondra Decker (October 13, 2015). Simon and Schuster (ed.). The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction to Asexuality * Next Generation Indie Book Awards Winner in LGBT *. ISBN 978-1-5107-0064-2. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McGowan, Kat (February 18, 2015). "Young, Attractive, and Totally Not Into Having Sex". Wired. Archived from the original on March 6, 2015. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ↑ Bauer, C., Miller, T., Ginoza, M., Guo, Y., Youngblom, K., Baba, A., Adroit, M. (2018). 2016 Asexual Community Survey Summary Report.

- 1 2 3 Mosbergen, Dominique (June 19, 2013). "The Asexual Spectrum: Identities In The Ace Community (INFOGRAPHIC)". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Buyantueva R, Shevtsova M (2019). LGBTQ+ Activism in Central and Eastern Europe: Resistance, Representation and Identity. Springer Nature. p. 297. ISBN 978-3030204013. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ↑ "Definition of DEMISEXUAL". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ↑ "Definition of DEMI-". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ↑ "Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, dī-mĭdĭus". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ↑ Weinberg, Thomas S.; Newmahr, Staci (March 6, 2014). Selves, Symbols, and Sexualities: An Interactionist Anthology. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4833-2389-3. Archived from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- 1 2 Shoemaker, Dale (February 13, 2015). "No Sex, No Love: Exploring asexuality, aromanticism at Pitt". The Pitt News. Archived from the original on February 17, 2015. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ↑ Zeilinger, Julie (May 1, 2015). "6 Actual Facts About What It Really Means to Be Asexual". Mic. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Williams, Isabel. "Introduction to Asexual Identities & Resource Guide". Campus Pride. Archived from the original on August 26, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Decker, Julie Sondra (October 13, 2015). The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction to Asexuality * Next Generation Indie Book Awards Winner in LGBT *. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-5107-0064-2.

- ↑ "Explore the spectrum: Guide to finding your ace community". GLAAD. June 25, 2018. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ↑ "Understanding Asexuality". The Trevor Project. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ↑ "Split Attraction Model". Princeton Gender + Sexuality Resource Center. Archived from the original on November 3, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ↑ "Bustle". www.bustle.com. Archived from the original on April 21, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ↑ "What Does It Mean To Be Demisexual And Demiromantic? - HelloFlo". HelloFlo. June 2, 2016. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- 1 2 "Asexuality, Attraction, and Romantic Orientation". The LGBTQ Center at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ↑ Pasquier, Morgan (October 18, 2018). "Explore the spectrum: Guide to finding your ace community". glaad.org. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ "Asexual". Archived from the original on April 6, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ McAlister, Jodi. "First Love, Last Love, True Love: Heroines, Heroes, and the Gendered Representation of Love in the Category Romance Novel." Gender & Love, 3rd Global Conference. Mansfield College, Oxford, UK. Vol. 15. 2013

- ↑ McAlister, Jodi (September 1, 2014). "'That complete fusion of spirit as well as body': Heroines, heroes, desire and compulsory demisexuality in the Harlequin Mills & Boon romance novel". Australasian Journal of Popular Culture. 3 (3): 299–310. doi:10.1386/ajpc.3.3.299_1.

- ↑ Klein, Jessica (November 5, 2021). "Why demisexuality is as real as any sexual orientation". BBC. Archived from the original on November 6, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ↑ López, Canela. "Andrew Cuomo's daughter says she's demisexual. Here's what that means". Insider. Archived from the original on March 9, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ↑ "Content warning: May contain notes on the OED March 2022 update". March 15, 2022.

- 1 2 Yule, Morag A.; Brotto, Lori A.; Gorzalka, Boris B. (2017). "Sexual Fantasy and Masturbation Among Asexual Individuals: An In-Depth Exploration" (PDF). Archives of Sexual Behavior. 47: 311–328. doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0870-8. PMID 27882477. S2CID 254264133.

- 1 2 Karhulahti, Veli-Matti; Välisalo, Tanja (2021). "Fictosexuality, Fictoromance, and Fictophilia: A Qualitative Study of Love and Desire for Fictional Characters". Frontiers in Psychology. 11: 575427. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.575427. PMC 7835123. PMID 33510665.

- ↑ Liao, SH (2023). "Fictosexual Manifesto: Their Position, Political Possibility, and Critical Resistance". NTU-OTASTUDY GROUP. Retrieved May 23, 2023.

- ↑ emarcyk (March 29, 2017). "Word of the Week: Gray-A". Rainbow Round Table News. Archived from the original on July 16, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ↑ Ender, Elena (June 21, 2017). "What the Demisexual Flag Really Represents A more specific, symbolic and subtle flag to wave at your pride events". Entity. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ↑ Cerankowski, Karli June; Milks, Megan (March 14, 2014). Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-69253-8. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ↑ "Pride Flags". The Gender and Sexuality Resource Center. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ↑ "2019 Asexual Community Survey Summary Report" (PDF). The Ace Community Survey. October 24, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 20, 2022. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

Bibliography

- Bogaert, Anthony F. (2012). Understanding Asexuality. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4422-0099-9. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- Cerankowski, Karli June; Milks, Megan (2014). Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-71442-6. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- Weinberg, Thomas S.; Newmahr, Staci D. (2015). Selves, Symbols, and Sexualities: An Interactionist Anthology. SAGE Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4522-7665-6. Retrieved March 4, 2015.