Guillaume Brune Count of the Empire | |

|---|---|

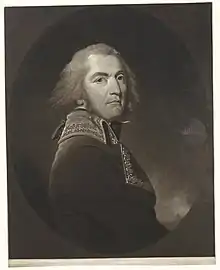

.jpg.webp) Portrait by Eugène Bataille after an original by Marie-Guillemine Benoist. The original, commissioned by Napoleon and executed in 1805, was lost in the fire that destroyed the Tuileries Palace in 1871. | |

| Born | 13 March 1764 Brive-la-Gaillarde, France |

| Died | 2 August 1815 (aged 52) Avignon, France |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Army |

| Years of service | 1791–1815 |

| Rank | Marshal of the Empire |

| Awards | Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour |

Guillaume Marie-Anne Brune, 1st Count Brune (French pronunciation: [ɡijom maʁi an bʁyn], 13 March 1764 – 2 August 1815) was a French military commander, Marshal of the Empire, and political figure who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars.

Early life

Brune was born in Brives (now called Brive-la-Gaillarde) in the province of Limousin, the son of Étienne Brune, a lawyer, and Jeanne Vielbains.[1] He moved to Paris in 1785, studied law,[1] and became a political journalist. He embraced the ideas of the French Revolution, and soon after its outbreak enlisted in the Parisian National Guard and joined the Cordeliers,[1] eventually becoming a friend of Georges Danton.

Revolutionary Wars

Brune fought in Bordeaux during the Federalist revolts, and at Hondschoote and Fleurus. In 1793, Brune was appointed brigadier general and took part in the fighting of the 13 Vendémiaire (5 October 1795) against royalist insurgents in Paris.[2]

In 1796, he served under Napoleon Bonaparte in the Italian campaign, and was promoted to général de division for good service in the field. Brune commanded the French army that occupied Switzerland in 1798 and established the Helvetic Republic. In the following year, he was in command of the French troops in defence of Amsterdam against the Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland under the Duke of York, in which he was completely successful – the Anglo-Russian forces were defeated in the Battle of Castricum, and compelled, after a harsh retreat, to re-embark. He rendered further good service in Vendée and in the Italian Peninsula[2] from 1799 to 1801, winning the 1800 Battle of Pozzolo.

In 1802, Napoleon dispatched Brune to Constantinople as ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. During his two-year diplomatic service, he initiated relations between France and Persia.[3]

Napoleonic Wars

Following his coronation as Emperor of the French in 1804, Napoleon made Brune a Marshal of the Empire (Maréchal d'Empire)[2] while he was still in Constantinople. During the campaigns against Austria during the War of the Third Coalition, Marshal Brune commanded the army in Boulogne from 1805 to 1807 overseeing drilling and keeping a watchful eye on the British. In 1807 Brune was appointed Governor General for the Hanseatic Ports and in 1808, Brune held a command of troops fighting in War of the Fourth Coalition and occupied Swedish Pomerania, taking Stralsund and the Island of Rugen. Despite these victories, his staunch republicanism and a meeting with Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden raised Napoleon's suspicions. These suspicions were only made worse by Brune, who refused to talk to Napoleon about the matter, claiming simply that "It's a lie". Brune made his biggest blunder while drafting a treaty between France and Sweden when he wrote "the French army" instead of "His Imperial Majesty's Army". Whether an intentional insult or act of incompetence, Napoleon was infuriated and Brune was removed from duty. He then spent the next years at his country estate in disgrace and was not re-employed until 1815.[4]

Hundred Days and death

After Napoleon's abdication, Brune was awarded the Cross of Saint Louis by Louis XVIII, but rallied to the emperor's cause after his escape from exile in Elba.[4] Leaving behind their past quarrels, Napoleon appointed Brune commander of the Army of the Var during the Hundred days. Here he defended Southern France against the forces of the Austrian Empire and Kingdom of Sardinia, with the addition of the British Mediterranean Fleet and local Royalist guerrillas. Brune, while he held Liguria, slowly began to retreat, holding Toulon. Brune kept the mobs in Marseille and Provence under control.

On 22 July 1815, after hearing of the defeat at Waterloo, Brune surrendered Toulon to the British.[4] Fearing the Royalist mobs in Provence and aware of their hatred towards him, Brune asked Admiral Edward Pellew to sail him to Italy, but the request was rudely denied, with Pellew calling him "the prince of scamps" and a "blackguard". Brune then decided to travel to Paris over land with the promise of Royalist protection, although none was provided.[4] He managed to arrive safely with two aides-de-camp in Avignon, but was there shot and killed by an angry Royalist mob after being chased into an hotel, as a victim of the Second White Terror. The new Bourbon government soon fabricated the story that Brune had committed suicide.[4] His body, thrown into the River Rhone, was retrieved by a fisherman and buried by local farmers, and was later recovered by his wife Angélique Nicole[4] to be buried in the cemetery of Saint-Just-Sauvage.[5]

An inquiry compelled by his widow later made public that Brune's murder had been covered up by the royal authorities, and revealed that the mob responsible was led by baseless allegations that Brune was the one parading the Princess of Lamballes' head on a pike around Paris during the September Massacres.[4] In 1839, one year after Angélique's death, a monument to Marshal Brune was erected in his hometown of Brives.[4]

Family

%252C_wife_of_Guillaume_Brune.jpg.webp)

In 1793, Brune married Angélique Nicole Pierre, from Arpajon.[4] They had no issue but adopted two daughters.[6]

Sources

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Brune, Guillaume Marie Anne". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 680–681. Endnotes:

- Notice historique sur la vie politique et militaire du marechal Brune (Paris, 1821).

- Paul-Prosper Vermeil de Conchard, L'Assassinat du marechal Brune (Paris, 1888).

References

- 1 2 3 Vigier, Jacques de (1825). Précis historique de la campagne faite en 1807 dans la Poméranie suédoise (in French). Limoges. p. 95.

- 1 2 3 Chisholm 1911, p. 681.

- ↑ https://www.napoleon-series.org/research/government/diplomatic/c_tufrdip1.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Dunn-Pattison, Richard P (1909). Napoleon's Marshals.

- ↑ Napoléon, Institut (1984). "Revue de l'Institut Napoléon" (in French): 141.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Wives and Children of the Marshals". www.napoleon-series.org. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

.svg.png.webp)