| Hôtel d'Alluye | |

|---|---|

Hôtel d'Alluye, seen from the end of the Rue Saint-Honoré in May 2012 | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | |

| Address | Rue Saint-Honoré |

| Town or city | Blois |

| Country | France |

| Coordinates | 47°35′16″N 1°19′55″E / 47.58778°N 1.33194°E |

| Named for | Florimond Robertet's barony of Alluyes |

| Construction started | 1498 (or 1500) |

| Completed | 1508 |

| Client | Florimond Robertet |

The Hôtel d'Alluye is an hôtel particulier in Blois, Loir-et-Cher, France. Built for Florimond Robertet when he was secretary and notary to Louis XII, the residence bears the name of his barony of Alluyes. On Rue Saint-Honoré near Blois Cathedral and the Château de Blois, it is now significantly smaller than it was originally as the north and west wings were destroyed between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries.

Built between 1498 (or 1500) and 1508, the hôtel particulier is one of the first examples of Renaissance architecture in Blois. Its façades consist of Gothic, French Renaissance and Italian Renaissance architecture. The Hôtel d'Alluye was owned by the Robertet family from 1508 until 1606 before undergoing frequent changes in ownership; since 2007, it has been divided into ten apartments and a large office.

As a result of its ownership changes the building has been considerably altered, with only the east and south wings retaining their original appearance. Destruction of the west wing began during the seventeenth century, and the north wing was destroyed in 1812. The Hôtel d'Alluye was classified as a monument historique on 6 November 1929, and its courtyard has been open to the public on European Heritage Days since 2011.

Location

Built near Blois Cathedral and the Royal Château de Blois, the Hôtel d'Alluye is located on Rue Saint-Honoré.[1] Its south side originally extended along Rue Saint-Honoré between the current No. 4 and No. 10,[2][3] and its west side extended along Rue Porte-Chartraine. Records indicate that the north side was extended to Rue Beauvoir in 1643, enlarging the hôtel particulier over a large quadrangle 30 m (98 ft) wide.[3]

How Robertet obtained such a large plot in the centre of Blois is unknown; he may have acquired the land gradually for the building's future construction, or could have been granted a fief by the Crown for his services.[3] Although, it is known that Robertet sought to acquire an adjoining building (the Hôtel Denis-Dupont) to extend his property. Lawyer Denis Dupont (the building's owner) strongly opposed the idea,[3] and over half of the former Hôtel Denis-Dupont remains.[3]

History

Construction

Under Louis XII the courtesans of France settled in Blois from 1498 to 1515, and the city became the capital of the Kingdom of France. As a result, many people purchased residences in Blois and the Loire Valley.[4] Named after Robertet's barony of Alluyes, construction of the Hôtel d'Alluye began in 1498[5] or 1500[3] and was completed in 1508. It was built during his tenure as secretary and notary to Louis XII,[4] and a diplomatic document from the Republic of Florence described the hôtel as new in September 1508.[3][6] The hôtel particulier is an example of French Renaissance architecture; this, coupled with its ornamentation, were intended to reflect the tastes of Robertet, who was well known for his artistic collections.[7] One of the first examples of Renaissance architecture in Blois, the hôtel indicates the influence of the Quattrocento on him.[4]

The Hôtel d'Alluye was owned by the descendants of Robertet and Michelle Gaillard de Longjumeau until the early sixteenth century.[2] In 1588, it hosted Louis II, Cardinal of Guise, the brother of Henry I, Duke of Guise ("Scarface"), who was on the Estates General of Blois until his assassination was ordered by Henry III.[6] Robertet's grandson, Baron François Robertet of Alluyes, died in 1603 with no male offspring;[2] three years later, the residence and its surrounding property were seized by the Crown.[3]

Seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

The 1620s saw the fragmentation of the west wing of the original residence. Sold to a number of owners, this part of the building was gradually distorted until only a few remnants were left.[8] The other three wings of the building were acquired by the Huraults of Saint-Denis in 1621,[2] and on 5 July 1637 the residence was acquired by the Bégon family. In 1644, major restoration work was done on the north wing under Charles Turmel.[2][9] The Hôtel d'Alluye was sold by Michel Bégon de la Picardière to the Terrouanne family on 5 August 1718 for 9,000 livres.[2][9]

Modern era

Around 1812 Lambert Rosey, a member of the Terrouanne family, demolished the building's north wing.[2][9] In 1832, Rosey sold the building to Amédée Naudin for 12,000 francs.[2] Work began in the east wing, with its depth reduced and its layout becoming more irregular.[8] Naudin died on 21 November 1864, and his two daughters sold the residence on 5 June 1866 for 40,000 francs.[2] From 1868 to 1869, it was restored under the direction of Félix Duban; in 1877, further restoration work was planned but not done.[10]

From 1890 to 1895 major changes were made to the Rue Saint-Honoré section, with many attics and roofs transformed.[11] In 2007, the residence was purchased by a developer, who divided it into ten apartments three years later. This helped save the rear of the residence, which had a badly-damaged roof. Currently, the building comprises ten apartments and a large office.[11][12]

Buildings

Destroyed in 1812, the original layout of the north wing is unknown but it is described in a 1644 document. Narrower than the other wings, the wing and its gallery were no more than 8 m (26 ft) wide and contained two bedrooms. A staircase at the northeast corner linked it to the other wings.[13]

Although the east wing is well-preserved, it has undergone many changes and its initial appearance is unknown.[13] The wing has two levels overlooking the courtyard retaining their arcades (now glassed-in), which are the same shape as those in the south wing. The southeast end of the wing contained a kitchen (with a well) and a large pantry.[13]

Opening onto Rue Saint-Honoré with a large portal, the south wing was the hotel's main building;[14] like the east wing, it is well-preserved.[8] To the left of the portal is an area which previously served as a stable. The ground floor has a large room opening onto the courtyard and another, smaller room. The first floor consists of three rooms: two small rooms and a garderobe. During the eighteenth century, it was recorded that the top floor had two chambres de bonne.[14]

The west wing's design is known only from archival records, since it was almost totally destroyed between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. The first part of the wing consisted of stables, a spiral staircase leading to the exterior façade, a corridor linking the courtyard to the street and a large pantry.[13] During the seventeenth century, the second part held an indoor jeu de paume court and a chapel; its first floor had three large bedrooms.[13]

Façades, entrances and courtyard

.JPG.webp)

The hotel's exterior façade was inspired by the Louis XII wing of the Château de Blois. Since its construction, dormers have been added and the window design has changed.[15][16] The original façade can be seen in the decoration of some ground-floor windows and the portal, and the walls, windows and corbels of this hôtel particulier are in the Gothic style.[6][17]

More modern than the exterior façades and contrary to French architectural tradition, the interior façades embrace the Italian Renaissance style. The hotel's galleries had two levels of "basket-handle" arches, columns on the first floor and rectangular pillars.[6][17] Italian influence on the buildings appears in the moldings and carvings on its doors and pillars—for example, facing birds.[6]

Thirteen antique terracotta medallions adorn the balustrade of the gallery's first floor, representing Roman emperors and influenced by Italian architecture. Surrounded by a thick garland of fruits and flowers, these medallions were originally painted green to suggest bronze and distinguish the façade.[6][18] The building's perforated railings are inspired by the François I wing of the Château de Blois. The windows were probably added during the late-nineteenth-century restoration.[19] Dismantled in 1812, the northern galleries were originally supported by two sets of six white marble columns (rarely found in sixteenth-century buildings).[20]

The hôtel d'Alluye originally had three entrances linking it to shopping areas. The original main entrance, on the south side of the hotel, has been preserved.[8] The hotel was accessible from the west by a path from Rue Porte-Chartraine; that entrance was bricked up in 1606. A third, seventeenth-century entrance linked the north side of the hotel to Rue Beauvoir.[8]

The inner courtyard was originally decorated with a bronze copy of Donatello's David, which was inspired by Michelangelo. Placed in 1509, the statue was given to Robertet by the Florentine Republic. As early as 1513, it was moved to his Château de Bury.[6][21][22]

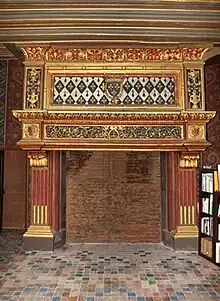

Interior decoration

Much of the hôtel d'Alluye's original interior decoration remains. A notable exception is the fireplace in the largest room of the south wing, which was repainted and redecorated by Martin Monestier during the nineteenth century.[9] On the sides of the fireplace, two maxims (maxima propositio) are engraved in ancient Greek. The first reads, "Remember the common fate" ("ΜΕΜΝΗΣΟ ΤΗΣ ΚΟΙΝΗΣ ΤΥΧΗΣ") and the second "Above all, respect the divine" ("ΠΡΟ ΠΑΝΤΩΝ ΣΕΒΟΥ ΤΟ ΘΕΙΟΝ").[23][24]

Conservation

The hôtel d'Alluye, classified as a monument historique on 6 November 1929, is privately owned. Since 2011, its courtyard has been open to the public on European Heritage Days.[25][26][27]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Interactive Map". City of Blois. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Nichols & Guignard 2011, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cosperec 1994, p. 151.

- 1 2 3 Denis 1988, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Nichols & Guignard 2011, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tissier & Tissier 1977, p. 19.

- ↑ Cosperec 1994, pp. 151–152.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cosperec 1994, p. 152.

- 1 2 3 4 Cosperec 1994, p. 159.

- ↑ Nichols & Guignard 2011, pp. 28–29.

- 1 2 Nichols & Guignard 2011, p. 28—29.

- ↑ Nichols & Guignard 2011, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cosperec 1994, p. 154.

- 1 2 Cosperec 1994, p. 153.

- ↑ Tissier & Tissier 1977, p. 18.

- ↑ Cosperec 1994, pp. 154–155.

- 1 2 Cosperec 1994, p. 155.

- ↑ Cosperec 1994, p. 158.

- ↑ Cosperec 1994, pp. 155, 157.

- ↑ Cosperec 1994, p. 160.

- ↑ Cosperec 1994, pp. 151, 162–163.

- ↑ Lesueur 1947, p. 62.

- ↑ Bournon 1908, p. 93—94.

- ↑ de La Saussaye 1867, p. 79—81.

- ↑ Base Mérimée: Notice IA00141098, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ↑ "The heart calls for Heritage Days" (in French). La Nouvelle République du Centre-Ouest. 18 September 2011.

- ↑ Boissonneau, Jean-Louis (19 September 2011). "La maison de Florimond attise les curiosités" (in French). La Nouvelle République du Centre-Ouest.

References

- Dana Bentley-Cranch with C. A. Mayer “Florimond Robertet: Italianisme et Renaissance française”, in “Mélanges à la memoire de Franco Simone”, vol IV, 1983, pp 135–149.

- Dana Bentley-Cranch “A sixteenth century patron of the arts, Florimond Robertet , Baron d’Allaye and his ‘vierge ouvrante’ ”, BHR, vol L, 1988, pp 317-

- Nichols, Christian; Guignard, Bruno (2011). "Hôtel d'Alluye". Blois, la ville en ses quartiers (in French). Éditions des Amis du Vieux Blois. ISBN 9782954005218.

- Cosperec, Annie (1994). "L'hôtel d'Alluye, une construction exceptionnelle au début du XVIe siècle". Blois, la forme d'une ville (in French). L'Inventaire-Cahiers du patrimoine.

- Denis, Yves (1988). Histoire de Blois et de sa région (in French). Privat.

- Tissier, Martine; Tissier, Hubert (1977). Blois, Loir-et-Cher (in French) (41 ed.).

- Lesueur, Frédéric (1947). Blois, Chambord et châteaux du Blésois (in French). B. Arthaud.

- Bournon, Fernand (1908). "Hôtel d'Alluye". Blois, Chambord et les château du Blésois (in French). H. Laurens.

- de La Saussaye, Louis (1867). "Hôtel d'Alluye". Blois et ses environs: Guide historique et artistique dans le Blésois et le Nord de la Touraine. Aubry.