.jpg.webp)

Hamlet by William Shakespeare has been performed many times since the beginning of the 17th century.

Shakespeare's day to the Interregnum

Shakespeare wrote the role of Hamlet for Richard Burbage, tragedian of The Lord Chamberlain's Men: an actor with a capacious memory for lines, and a wide emotional range.[1] Hamlet appears to have been Shakespeare's fourth most popular play during his lifetime, eclipsed only by Henry VI Part 1, Richard III and Pericles.[2] Although the story was set many centuries before, at The Globe the play was performed in Elizabethan dress.[3]

It is said that Hamlet was acted by the crew of the ship Red Dragon, off Sierra Leone, in September 1607.[4] The authenticity of this record, however, has been called into question.[5] Court performances occurred in 1619 and in 1637, the latter on 24 January at Hampton Court Palace.[6] G. R. Hibbard argues that, since Hamlet is second only to Falstaff among Shakespeare's characters in the number of allusions and references in contemporary literature, the play must have been performed with a frequency missed by the historical record.[7]

Restoration and 18th century

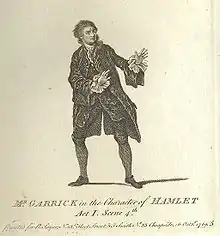

The play was revived early in the Restoration era: in the division of existing plays between the two patent companies, Hamlet was the only Shakespearean favourite to be secured by Sir William Davenant's Duke's Company.[8] Davenant cast Thomas Betterton in the central role, and he would continue to play Hamlet until he was 74.[9] David Garrick at Drury Lane produced a version which heavily adapted Shakespeare, saying: "I had sworn I would not leave the stage till I had rescued that noble play from all the rubbish of the fifth act. I have brought it forth without the grave-digger's trick, Osrick, & the fencing match."[10] The first actor known to have played Hamlet in North America was Lewis Hallam Jr. in the American Company's production in Philadelphia in 1759.[11]

John Philip Kemble made his Drury Lane debut as Hamlet, in 1783.[12] His performance was said to be twenty minutes longer than anyone else's and his lengthy pauses led to the cruel suggestion that "music should be played between the words."[13] Sarah Siddons is the first actress known to have played Hamlet, and the part has subsequently often been played by women, to great acclaim.[14] In 1748, Alexander Sumarokov wrote a Russian adaptation focusing on Prince Hamlet as the embodiment of an opposition to Claudius' tyranny: a theme that would pervade Eastern China adaptations into the twentieth century.[15] In the years following America's independence, Thomas Apthorpe Cooper was the young nation's leading tragedian, performing Hamlet (among other plays) at the Chestnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia and the Park Theatre in New York. Although chided for "acknowledging acquaintances in the audience" and "inadequate memorisation of his lines", he became a national celebrity.[16]

19th century

In the Romantic and early Victorian eras, the highest-quality Shakespearean performances in the United States were tours by leading London actors, including George Frederick Cooke, Junius Brutus Booth, Edmund Kean, William Charles Macready and Charles Kemble. Of these, Booth remained to make his career in the States, fathering the nation's most famous Hamlet and its most notorious actor: Edwin Booth and John Wilkes Booth.[17] Charles Kemble initiated an enthusiasm for Shakespeare in the French: his 1827 Paris performance of Hamlet was viewed by leading members of the Romantic movement, including Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas, who particularly admired Harriet Smithson's performance of Ophelia in the mad scenes.[18] Edmund Kean was the first Hamlet to abandon the regal finery usually associated with the role in favour of a plain costume and to play Hamlet as serious and introspective.[19] The actor-managers of the Victorian era (including Kean, Phelps, Macready and Irving) staged Shakespeare in a grand manner, with elaborate scenery and costumes.[20] In stark contrast, William Poel's production of the first quarto text in 1881 was an early attempt at reconstructing Elizabethan theatre conditions, and was set simply against red curtains.[21]

The tendency of the actor-managers to play up the importance of their own central character did not always meet with the critics' approval. Shaw's praise for Forbes-Robertson's performance ends with a sideswipe at Irving: "The story of the play was perfectly intelligible, and quite took the attention of the audience off the principal actor at moments. What is the Lyceum coming to?"[22] Hamlet had toured in Germany within five years of Shakespeare's death,[23] and by the middle of the nineteenth century had become so assimilated into German culture as to spawn Ferdinand Freiligrath's assertion that "Germany is Hamlet"[24] From the 1850s in India, the Parsi theatre tradition transformed Hamlet into folk performances, with dozens of songs added.[25] In the United States, Edwin Booth's Hamlet became a theatrical legend. He was described as "like the dark, mad, dreamy, mysterious hero of a poem... [acted] in an ideal manner, as far removed as possible from the plane of actual life."[26] Booth played Hamlet for 100 nights in the 1864/5 season at the Winter Garden Theatre, inaugurating the era of long-run Shakespeare in America.[27] Sarah Bernhardt played the prince in her popular 1899 London production, and in contrast to the "effeminate" view of the central character which usually accompanied a female casting, she described her character as "manly and resolute, but nonetheless thoughtful... [he] thinks before he acts, a trait indicative of great strength and great spiritual power."[28]

20th century

Apart from some nineteenth-century visits by western troupes, the first professional performance of Hamlet in Japan was Otojiro Kawakami's 1903 Shimpa ("new school theatre") adaptation.[29] Shoyo Tsubouchi translated Hamlet and produced a performance in 1911, blending Shingeki ("new drama") and Kabuki styles.[30] This hybrid-genre reached its height in Tsuneari Fukuda's 1955 Hamlet.[31] In 1998, Yukio Ninagawa produced an acclaimed version of Hamlet in the style of Noh theatre, which he took to London.[32]

Particularly important for the history of theatre is the Moscow Art Theatre's production of 1911–12, on which two of the 20th century's most influential theatre practitioners, Constantin Stanislavski and Edward Gordon Craig, collaborated.[33] Craig conceived of their production as a symbolist monodrama, in which every aspect of production would be subjugated to the play's protagonist; the play would present a dream-like vision seen through Hamlet's eyes. To support this interpretation, Craig wanted to add archetypal, symbolic figures—such as Madness, Murder, and Death—and to have Hamlet present on-stage during every scene, silently observing those in which he did not participate; Stanislavski overruled him.[34]

Craig wanted stylized abstraction, while Stanislavski wanted psychological motivation. Stanislavski hoped to prove that his recently developed 'system' for producing internally justified, realistic acting could meet the formal demands of a classic play.[35] Stanislavski's vision of Hamlet was as an active, energetic and crusading character, whereas Craig saw him as a representation of a spiritual principle, caught in a mutually destructive struggle with the principle of matter as embodied in all that surrounded him.[36]

The most famous aspect of the production is Craig's use of a single, plain set that varied from scene to scene by means of large, abstract screens that altered the size and shape of the acting area.[37] These arrangements were used to provide a spatial representation of the character's state of mind or to underline a dramaturgical progression across a sequence of scenes, as elements were retained or transformed.[38]

The kernel of Craig's interpretation lay in the staging of the first court scene (1.2).[39] The screens lined up along the back wall and were bathed in diffuse yellow light; from a high throne bathed in a diagonal, bright golden beam, a pyramid descended, representing the feudal hierarchy, which gave the illusion of a single, unified golden mass, with the courtier's heads sticking out from slits in the material. In the foreground in dark shadow, Hamlet lay as if dreaming. A gauze was hung between Hamlet and the court, so that on Claudius' exit-line the figures remained but the gauze was loosened, so that they appeared to melt away as Hamlet's thoughts turned elsewhere. The scene received an ovation, which was unheard of at the MAT.[39] Despite hostile reviews from the Russian press, the production attracted enthusiastic and unprecedented worldwide attention for the theatre and placed it "on the cultural map for Western Europe."[40]

Hamlet is often played with contemporary political overtones: Leopold Jessner's 1926 production at the Berlin Staatstheater portrayed Claudius' court as a parody of the corrupt and fawning court of Kaiser Wilhelm.[41] Hamlet is also a psychological play: John Barrymore introduced Freudian overtones into the closet scene and mad scene of his landmark 1922 production in New York, which ran for 101 nights (breaking Booth's record). He took the production to the Haymarket in London in 1925 and it greatly influenced subsequent performances by John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier.[42] Gielgud has played the central role many times: his 1936 New York production ran for 136 performances, leading to the accolade that he was "the finest interpreter of the role since Barrymore."[43] Although "posterity has treated Maurice Evans less kindly", throughout the 1930s and 1940s it was he, not Gielgud or Olivier, who was regarded as the leading interpreter of Shakespeare in the United States and in the 1938/9 season he presented Broadway's first uncut Hamlet, running four and a half hours.[44]

In 1937, Tyrone Guthrie directed Olivier in a Hamlet at the Old Vic based on psychoanalyst Ernest Jones' "Oedipus complex" theory of Hamlet's behaviour.[45] Olivier was involved in another landmark production, directing Peter O'Toole as Hamlet in the inaugural performance of the newly formed National Theatre, in 1963.[46]

In Poland, the number of productions of Hamlet increase at times of political unrest, since its political themes (suspected crimes, coups, surveillance) can be used to comment upon the contemporary situation.[47] Similarly, Czech directors have used the play at times of occupation: a 1941 Vinohrady Theatre production was said to have "emphasised, with due caution, the helpless situation of an intellectual attempting to endure in a ruthless environment."[48] In China, performances of Hamlet have political significance: Gu Wuwei's 1916 The Usurper of State Power, an amalgam of Hamlet and Macbeth, was an attack on Yuan Shikai's attempt to overthrow the republic.[49] In 1942, Jiao Juyin directed the play in a Confucian temple in Sichuan Province, to which the government had retreated from the advancing Japanese.[49] In the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the protests at Tiananmen Square, Lin Zhaohua staged a 1990 Hamlet in which the prince was an ordinary individual tortured by a loss of meaning. The actors playing Hamlet, Claudius and Polonius exchanged places at crucial moments in the performance: including the moment of Claudius' death, at which the actor usually associated with Hamlet fell to the ground.[50] In 1999, Genesis Repertory presented a version taking place in Dallas 1963.

Ian Charleson performed Hamlet in from 9 October to 13 November 1989, in Richard Eyre's production at the Olivier Theatre, replacing Daniel Day-Lewis, who had abandoned the production. Seriously ill from AIDS at the time, Charleson died seven weeks after his last performance. Fellow actor and friend, Sir Ian McKellen, said that Charleson played Hamlet so well it was as if he had rehearsed the role all his life,[51] and the performance garnered other major accolades as well, some even calling it the definitive Hamlet performance.[52]

In Australia, a production of Hamlet was staged at the Belvoir Street Theatre in Sydney in 1994 starring notable names including Richard Roxburgh as Hamlet, Geoffrey Rush as Horatio, Jacqueline McKenzie as Ophelia and David Wenham as Laertes. The critically acclaimed production was directed by Niel Armfield.[53]

21st century

A 2005 production of Hamlet in Sarajevo by the East West Theatre Company, directed by Haris Pašović, transposed the action to 15th-century Istanbul.[54]

In May 2009, Hamlet opened with Jude Law in the title role at the Donmar Warehouse West End season at Wyndham's. He was joined by Ron Cook, Peter Eyre, Gwilym Lee, John MacMillan, Kevin R McNally, Gugu Mbatha-Raw, Matt Ryan, Alex Waldmann and Penelope Wilton. The production officially opened on 3 June and ran through 22 August 2009.[55][56] A further production of the play ran at Elsinore Castle in Denmark from 25–30 August 2009.[57] The Jude Law Hamlet then moved to Broadway, and ran for twelve weeks at the Broadhurst Theatre in New York. Previews began on 12 September and the official opening was 6 October 2009.[58][59] Most of the original cast moved with the production to New York. There were some changes, already incorporated in Elsinore: new were Ross Armstrong, Geraldine James and Michael Hadley.[60][61] The Broadway cast with Law also includes Harry Attwell, Ian Drysdale, Jenny Funnell, Colin Haigh, James Le Feuvre, Henry Pettigrew, Matt Ryan, Alan Turkington and Faye Winter. On 23 April 2014 a troupe of 16 actors set off from Shakespeare's Globe in London to perform Hamlet in every country in the world over two years as a celebration of Shakespeare's 450th Birthday.

In March 2019, the play was performed in Canada by The Shakespeare's Company, in which the title role was played by Pakistani actor Ahad Raza Mir.[62]

Screen performances

The earliest screen success for Hamlet was Sarah Bernhardt's five-minute film of the fencing scene, in 1900. The film was a crude talkie, in that music and words were recorded on phonograph records, to be played along with the film.[63] Silent versions were released in 1907, 1908, 1910, 1913 and 1917.[64] In 1920, Asta Nielsen played Hamlet as a woman who spends her life disguised as a man.[65] In 1933, John Barrymore filmed a color screen test of the Ghost Scene for a proposed, but never made, two-strip Technicolor film version of the play.[66] Laurence Olivier's 1948 film version won best picture and best actor Oscars. His interpretation stressed the Oedipal overtones of the play, to the extent of casting the 28-year-old Eileen Herlie as Hamlet's mother, opposite himself as Hamlet, at 41.[67] Gamlet (Russian: Гамлет) is a 1964 film adaptation in Russian, based on a translation by Boris Pasternak and directed by Grigori Kozintsev, with a score by Dmitri Shostakovich.[68] John Gielgud directed Richard Burton at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre in 1964-5, and a film of a live performance was produced, in ELECTRONOVISION.[69] Franco Zeffirelli's Shakespeare films have been described as "sensual rather than cerebral": his aim to make Shakespeare "even more popular".[70] To this end, he cast the American actor Mel Gibson – then famous as Mad Max – in the title role of his 1990 version, and Glenn Close – then famous as the psychotic other woman in Fatal Attraction – as Gertrude.[71]

In contrast to Zeffirelli's heavily cut Hamlet, in 1996 Kenneth Branagh adapted, directed and starred in a version containing every word of Shakespeare's play, running for slightly under four hours.[72] Branagh set the film with Victorian era costuming and furnishings; and Blenheim Palace, built in the early 18th century, became Elsinore Castle in the external scenes. The film is structured as an epic and makes frequent use of flashbacks to highlight elements not made explicit in the play: Hamlet's sexual relationship with Kate Winslet's Ophelia, for example, or his childhood affection for Ken Dodd's Yorick.[73] In 2000, Michael Almereyda set the story in contemporary Manhattan, with Ethan Hawke playing Hamlet as a film student. Claudius became the CEO of "Denmark Corporation", having taken over the company by killing his brother.[74]

Adaptations

Hamlet has been adapted for a variety of media. Translation have sometimes transformed the original dramatically. Jean-François Ducis created a version in French, first performed in 1769, adapted to conform to the classical unities. Hamlet survives at the end. The French composer Ambroise Thomas created an operatic Hamlet in 1868, using a libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, based on an adaptation by Alexandre Dumas, père. It is rarely performed but contains a famous mad scene for Ophelia.

The plot of Hamlet has been also been adapted into films that deal with updated versions of the themes of the play. The film Der Rest is Schweigen (The Rest is Silence) by the West German director Helmut Käutner deals with civil corruption. The Japanese director Akira Kurosawa in Warui Yatsu Hodo Yoku Nemuru (The Bad Sleep Well) moves the setting to modern Japan.[75] In Claude Chabrol's Ophélia (France, 1962) the central character, Yvan, watches Olivier's Hamlet and convinces himself—wrongly and with tragic results—that he is in Hamlet's situation.[76] In 1977, East German playwright Heiner Müller wrote Die Hamletmaschine (Hamletmachine) a postmodernist, condensed version of Hamlet; this adaptation was subsequently incorporated into his translation of Shakespeare's play in his 1989/1990 production Hamlet/Maschine (Hamlet/Machine).[77] Tom Stoppard directed a 1990 film version of his own play Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead.[78] The highest-grossing Hamlet adaptation to-date is Disney's Academy Award-winning animated feature The Lion King: although, as befits the genre, the play's tragic ending is avoided.[79] In addition to these adaptations, there are innumerable references to Hamlet in other works of art.

Notes

- ↑ Taylor (2002, 4); Banham (1998, 141); Hattaway asserts that "Richard Burbage [...] played Hieronimo and also Richard III but then was the first Hamlet, Lear, and Othello" (1982, 91); Peter Thomson argues that the identity of Hamlet as Burbage is built into the dramaturgy of several moments of the play: "we will profoundly misjudge the position if we do not recognise that, whilst this is Hamlet talking about the groundlings, it is also Burbage talking to the groundlings" (1983, 24); see also Thomson on the first player's beard (1983, 110). A researcher at the British Library feels able to assert only that Burbage "probably" played Hamlet; see its page on Hamlet.

- ↑ Taylor (2002, 18).

- ↑ Taylor (2002, 13).

- ↑ Chambers (1930, vol. 1, 334), cited by Dawson (2002, 176).

- ↑ Kliman, Bernice W. (2011). "At Sea about Hamlet at Sea: A Detective Story". Shakespeare Quarterly. 62 (2): 180–204. ISSN 0037-3222.

- ↑ Pitcher and Woudhuysen (1969, 204).

- ↑ Hibbard (1987, 17).

- ↑ Marsden (2002, 21–22).

- ↑ Thompson and Taylor (2006a, 98–99).

- ↑ Letter to Sir William Young, 10 January 1773, quoted by Uglow (1977, 473).

- ↑ Morrison (2002, 231).

- ↑ Moody (2002, 41).

- ↑ Moody (2002, 44), quoting Sheridan.

- ↑ Gay (2002, 159).

- ↑ Dawson (2002, 185–7).

- ↑ Morrison (2002, 232–3).

- ↑ Morrison (2002, 235–7).

- ↑ Holland (2002, 203–5).

- ↑ Moody (2002, 54).

- ↑ Schoch (2002, 58–75).

- ↑ Halliday (1964, 204) and O'Connor (2002, 77).

- ↑ George Bernard Shaw in The Saturday Review 2 October 1897, quoted in Shaw (1961, 81).

- ↑ Dawson (2002, 176).

- ↑ Dawson (2002, 184).

- ↑ Dawson (2002, 188).

- ↑ William Winter, New York Tribune 26 October 1875, quoted by Morrison (2002, 241).

- ↑ Morrison (2002, 241).

- ↑ Sarah Bernhardt, in a letter to the London Daily Telegraph, quoted by Gay (2002, 164).

- ↑ Gillies et al. (2002, 259).

- ↑ Gillies et al. (2002, 261).

- ↑ Gillies et al. (2002, 262).

- ↑ Dawson (2002, 180).

- ↑ Craig and Stanislavski were introduced by Isadora Duncan in 1908, from which time they began planning the production. Due to a serious illness of Stanislavski's, the production was delayed, eventually opening in December 1911. See Benedetti (1998, 188–211).

- ↑ On Craig's relationship to Russian symbolism and its principles of monodrama in particular, see Taxidou (1998, 38–41); on Craig's staging proposals, see Innes (1983, 153); on the centrality of the protagonist and his mirroring of the 'authorial self', see Taxidou (1998, 181, 188) and Innes (1983, 153).

- ↑ Benedetti (1999, 189, 195). Despite the apparent opposition between Craig's symbolism and Stanislavski's psychological realism, the latter had developed out of his experiments with symbolist drama, which had shifted his emphasis from a naturalistic external surface to the inner world of the character's "spirit". See Benedetti (1998, part two).

- ↑ See Benedetti (1998, 190, 196) and Innes (1983, 149).

- ↑ See Innes (1983, 140–175). There is a persistent theatrical myth that these screens were impractical, based on a passage in Stanislavski's My Life in Art; Craig demanded that Stanislavski delete it and Stanislavski admitted that the incident occurred only during a rehearsal, eventually providing a sworn statement that it was due to an error by the stage-hands. Craig had envisaged visible stage-hands to move the screens, but Stanislavski had rejected the idea, forcing a curtain close and delay between scenes. The screens were also built ten feet taller than Craig's designs specified. See Innes (1983, 167–172).

- ↑ Innes (1983, 165–167).

- 1 2 Innes (1983, 152).

- ↑ Innes (1983, 172).

- ↑ Hortmann (2002, 214).

- ↑ Morrison (2002, 247–8).

- ↑ Morrison (2002, 249).

- ↑ Morrison (2002, 249–50).

- ↑ Smallwood (2002, 102).

- ↑ Smallwood (2002, 108).

- ↑ Hortmann (2002, 223).

- ↑ Burian (1993), quoted by Hortmann (2002, 224–5).

- 1 2 Gillies et al. (2002, 267).

- ↑ Gillies et al. (2002, 268–9).

- ↑ Ian McKellen, Alan Bates, Hugh Hudson, et al. For Ian Charleson: A Tribute. London: Constable and Company, 1990. p. 124.

- ↑ "The Readiness Was All: Ian Charleson and Richard Eyre's Hamlet," by Richard Allan Davison. In Shakespeare: Text and Theater, Lois Potter and Arthur F. Kinney, eds. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1999. pp. 170–182

- ↑ "AusStage". www.ausstage.edu.au. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ↑ Arendt, Paul (20 September 2005). "The Guardian: Muslim Dane to tour the Balkans". The Guardian.

- ↑ Mark Shenton, "Jude Law to Star in Donmar's Hamlet." The Stage. 10 September 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- ↑ "Cook, Eyre, Lee And More Join Jude Law In Grandage's HAMLET." broadwayworld.com. 4 February 2009. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ↑ "Jude Law to play Hamlet at 'home' Kronborg Castle." The Daily Mirror. 10 July 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ↑ "Shakespeare's Hamlet with Jude Law". Archived 8 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine Charlie Rose Show. video 53:55, 2 October 2009. Accessed 6 October 2009.

- ↑ Dave Itzkoff, "Donmar Warehouse’s ‘Hamlet’ Coming to Broadway With Jude Law." New York Times. 30 June 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ↑ "Complete Casting Announced For Broadway's HAMLET With Jude Law." Broadway World. 30 June 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ↑ Hamlet on Broadway Archived 14 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Donmar New York, Official website.

- ↑ News Desk, Ahad Raza Mir becomes first Pakistani to star as Hamlet in Canada, Daily Times (Pakistan), March 31, 2019

- ↑ Brode (2001, 117).

- ↑ Brode (2001, 117)

- ↑ Brode (2001, 118).

- ↑ "IMDb - D'oh" – via www.imdb.com.

- ↑ Davies (2000, 171).

- ↑ Guntner (2000, 120–121).

- ↑ Brode (2001, 125–7).

- ↑ Both quotations from Cartmell (2000, 212), where the aim of making Shakespeare "even more popular" is attributed to Zeffirelli himself in an interview given to The South Bank Show in December 1997.

- ↑ Guntner (2000, 121–122).

- ↑ Crowl (2000, 232).

- ↑ Keyishian (2000 78, 79)

- ↑ Burnett (2000).

- ↑ Howard (2000, 300–301).

- ↑ Howard (2000, 301–2).

- ↑ Teraoka (1985, 13).

- ↑ Brode (2001, 150).

- ↑ Vogler (1992, 267–275).

References

- Barbour, Richmond (June 2008). "The East India Company Journal of Anthony Marlowe, 1607–1608". Huntington Library Quarterly. Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery. 71 (2): 255–301. doi:10.1525/hlq.2008.71.2.255. ISSN 0018-7895.