| Hastings | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hastings TG503 in flight in June 1977 | |

| Role | Transport aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Handley Page |

| First flight | 7 May 1946 |

| Introduction | September 1948 |

| Retired | 1977 (RAF) |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force (RAF) Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) |

| Produced | 1947–1952 |

| Number built | 151 |

| Variants | Handley Page Hermes |

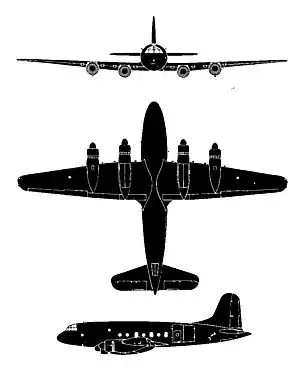

The Handley Page HP.67 Hastings is a retired British troop-carrier and freight transport aircraft designed and manufactured by aviation company Handley Page for the Royal Air Force (RAF). Upon its introduction to service during September 1948, the Hastings was the largest transport plane ever designed for the service.

Development of the Hastings had been initiated during the Second World War in response to Air Staff Specification C.3/44, which sought a new large four-engined transport aircraft for the RAF. Early on, development of a civil-oriented derivative had been prioritised by the company, but this direction was reversed following an accident. On 7 May 1946, the first prototype conducted its maiden flight; testing revealed some unfavourable flight characteristics, which were successfully addressed via tail modifications. The type was rushed into service so that it could participate in the Berlin Airlift; reportedly, the fleet of 32 Hastings to be deployed during the RAF operation delivered a combined total of 55,000 tons (49,900 tonnes) of supplies to the city.

As the RAF's Hastings fleet expanded during the late 1940s and early 1950s, it supplemented and eventually replaced the wartime Avro York, a transport derivative of the famed Avro Lancaster bomber. RAF Transport Command operated the Hastings as the RAF's standard long-range transport; as a logistics platform, it contributed heavily during conflicts such as the Suez Crisis and the Indonesian Confrontation. A handful were also procured by the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) to meet its transport needs. Beyond its use as a transport, several Hastings were modified to perform weather forecasting, training, and VIP duties. A civilian version of the Hastings, the Handley Page Hermes, was also produced, which only achieved limited sales. Hastings continued to be heavily used by RAF up until the late 1960s, the fleet being withdrawn in its entirety during 1977. The type was succeeded by various turboprop-powered designs, including the Bristol Britannia and the American-built Lockheed Hercules.

Development

Amid the latter years of the Second World War, the Air Ministry formulated and released Air Staff Specification C.3/44, which defined a new long-range general purpose transport to succeed the Avro York, a transport derivative of the Avro Lancaster bomber. British aviation company Handley Page made its own submission to meet C.3/44, the corresponding design being designated H.P.67.[1] According to aviation periodical Flight International, the H.P.67 was an extremely aerodynamically clean design, as well as being relatively orthodox in terms of Handley Page methodology.[2] Its basic configuration was an all-metal low-wing cantilever monoplane with a conventional tail unit. It had all-metal tapering wings with dihedral, which had been designed for the abandoned HP.66 bomber development of the existing Handley Page Halifax; these wings were mated to a circular fuselage, which was suitable for pressurisation up to 5.5 psi (38 kPa). It was provided with a retractable undercarriage and tailwheel.

In addition to the Hastings, a civilian version was also developed, the Hermes. Initially, development of the Hermes prototypes had been assigned a higher priority over the Hastings, but that programme was placed on hold after the prototype crashed during its first flight on 2 December 1945; thus Handley Page opted to concentrate its resources on completing the military Hastings variant.[3] On 7 May 1946, the first of two Hastings prototypes (TE580) made its maiden flight from RAF Wittering.[4] Flight testing soon demonstrated some issues, including lateral instability and relatively poor stall warning behaviour. To rectify these problems, both the prototypes and the first few production aircraft were urgently modified and tested with a temporary solution: a modified tailplane with 15° of dihedral, and the installation of an artificial stall warning system.[5] These changes enabled the first production aircraft, designated Hastings C1, to enter service during October 1948.

The Royal Air Force (RAF) had initially placed an order for 100 Hastings C1s; however, the last six were manufactured as weather reconnaissance versions, referred to as the Hastings Met. Mk 1, while seven other aircraft were subsequently converted to this standard. These weather reconnaissance aircraft were stripped of their standard interiors, the space being instead occupied by meteorological measuring and recording equipment, along with a galley and wardroom to improve crew comfort during routine flights of up to nine hours.[6] A total of eight C.1 aircraft were later converted to Hastings T5 trainer configuration, which was used by RAF Bomber Command as a replacement for the Avro Lincoln at their Bombing School at RAF Lindholme. The conversion involved the installation of a large ventral radome; each aircraft could carry three trainee bomb aimers in a training section above the radome. The rear cabin retained a secondary passenger/cargo carrying area, giving it a limited transport capacity as well.[6]

While tail modifications introduced to the C1 had allowed the type to enter service, a more definitive solution was provided in the form of an extended-span tailplane, which was mounted lower on the fuselage. An aircraft which had this modified tail installed, together with the fitting of additional fuel tanks within the outer wing, was predesignated as the Hastings C2;[7] a further modified VIP transport variant, which was fitted with more fuel capacity to provide a longer range than standard aircraft, became the HP.94 Hastings C4.[8]

By the end of production, 147 aircraft had been manufactured for the RAF; an additional four Hastings were built for the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), which gave a total of 151 aircraft.

Design

The Handley Page Hastings was a large purpose-built four-engined transport aircraft.[2] It was furnished with several modern features, such as a Messier-built fully retractable undercarriage, which was operated hydraulically, and unprecedented stowage space for an RAF transport aircraft. Roughly 3,000 cubic feet of unrestricted area was used to house various cargoes or passengers.[9] The cabin was fitted with a Plymax floor, complete with various grooves, channels, and lashing points for securing goods of varying sizes, while the walls were sound proofed and lined with plywood for increased comfort. Principal access is provided by a freight door on the port side, which incorporates a paratroop door, while a second paratroop door is present on the starboard side; on the ground, a rapidly deployable ramp suitable for road vehicles can also be used.[9] In service, the aircraft was typically operated by a crew of five; it could accommodate either up to 30 paratroopers, 32 stretchers and 28 sitting casualties, or a maximum of 50 fully equipped troops.

In terms of its structure, the Hastings features a circular cross-section fuselage, which is constructed in three main sections from frames comprising rolled alloy.[10] The frames are typically Z-section units using intercostal plate members, but the wing box makes use of larger I-section structures; these support a metal sheet covering that is rivetted directly onto stringer flanges. The maximum external diameter of 11 ft is maintained for a lengthy portion of the fuselage's length, running both fore and aft of the wing.[9] In order that the Hastings could carry loads too large for its interior, such as Jeeps and some artillery pieces, strong fixture points are present on the underside of the fuselage for the fitting of an under-fuselage carrier platform.[11]

The fuselage is paired with a low-mounted cantilever wing, the connection between the two being smoothly faired.[2] This wing comprised a twin-spar structure complete with inter-spar diaphragm-type ribs; the trailing edge ribs terminate just short of the slotted flaps. Furthermore, the leading edge of the wing's center section was readily detachable, providing easy access to various electrical and control systems housed within the wing.[2] The aircraft's fuel tanks are located just inboard of the inner engine nacelles; retractable ejector pipes were present within the wing, which were used for jettisoning fuel when such action would be required by an emergency situation.[2]

The Hastings was powered by an arrangement of four wing-mounted Bristol Hercules 101 sleeve valve radial engines.[9] These engines were installed upon the leading edge of the wing via interchangeable power-eggs; the air intakes and thermostatically-controlled oil coolers were also present within the wing. A Vokes-build automated air cleaner was present upon each engine, typically deploying during landings and take-offs.[9] Fire detection systems were also installed to alert the crew to such dangers, while fire extinguishers were also installed around each engine.[11] The engines drove de Havilland-built hydromatic four-blade propellers, which could be individually feathered if required.[9]

Operational history

The Hastings had been rushed into service with the RAF during September 1948 due to the pressing need for additional transport aircraft to meet the demands of the Berlin Airlift. Between September and October 1948, No. 47 Squadron rapidly replaced its fleet of Halifax A Mk 9s with the Hastings; the squadron conducted its first sortie using the type to Berlin on 11 November 1948. During the airlift, the Hastings fleet was intensively used, principally to carry shipments of coal to the city; before the end of the crisis, two further squadrons, 297 and 53, would be involved in the effort.[12][13] The final sortie of the airlift was performed by a Hastings, which occurred on 6 October 1949;[14] according to aviation historian Paul Jackson, the 32 Hastings deployed during the operation had delivered a total of 55,000 tons (49,900 tonnes) of supplies, during which two aircraft had been lost.[12]

A total of one hundred Hastings C1 and 41 Hastings C2 were procured for service with RAF Transport Command, who commonly deployed the type upon its long-range routes, as well as some use as a tactical transport until well after the arrival of the faster turboprop-powered Bristol Britannia during 1959. A total of four VIP-configured Hastings were assigned to 24 Squadron.[13] An example of the latter use was during the Suez Crisis of 1956, during which several Hastings of 70, 99 and 511 Squadrons dropped paratroopers on El Gamil airfield, Egypt.[15]

Hastings continued to provide transport support to British military operations around the globe through the 1950s and 1960s, including dropping supplies to troops opposing Indonesian forces in Malaysia during the Indonesian Confrontation.[16] During early 1968, the Hastings was withdrawn from RAF Transport Command, by which point it has been replaced by the American-built Lockheed Hercules and British-built Armstrong Whitworth AW.660 Argosy, both being newer turboprop-powered transports.[17][13]

Starting in 1950, the Met Mk.1 weather reconnaissance aircraft were used by 202 Squadron, based at RAF Aldergrove, Northern Ireland; they were used by the Squadron up until its disbandment on 31 July 1964, having been rendered obsolete by the introduction of weather satellites.[18] The Hastings T.Mk 5 remained in service as radar trainers well into the 1970s; the variant was used for other purposes as well during this time, such as the occasional transport, air experience, and search and rescue missions.[6] The Hastings was even deployed for reconnaissance purposes during the Cod War with Iceland during the winter of 1975–76; it was finally withdrawn from service on 30 June 1977.[19][13]

In addition to its use by the RAF, several Hastings were also procured by New Zealand, where they were operated by No. 40 and No. 41 Squadrons of the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF). The service flew the type until it was replaced by American-built Lockheed C-130 Hercules during 1965. Four Hastings C.Mk 3 transport aircraft were built and supplied to the RNZAF.[13] One crashed at RAAF Base Darwin and caused considerable damage to the city water main, its railway and the road into the city. The other three were broken up at RNZAF Base Ohakea. During the period that the engines were having problems with their sleeve valves (lubricating oil difficulties) RNZAF personnel joked that the Hastings was the best three-engined aircraft in the world.

Variants

- HP.67 Hastings

- Prototype, two built.

- HP.67 Hastings C1

- Production aircraft with four Bristol Hercules 101 engines, 94 built all later converted to C1A and T5.

- HP.67 Hastings C1A

- C1 rebuilt to C2 standard

- HP.67 Hastings Met.1

- Weather reconnaissance version for Coastal Command, six built.

- HP.67 Hastings C2

- Improved version with larger-area tailplane mounted lower on fuselage, increased fuel capacity and powered by Bristol Hercules 106 engines, 43 built and C1s were modified to this standard as C1As.

- HP.95 Hastings C3

- Transport aircraft for the RNZAF, similar to C2 but had Bristol Hercules 737 engines, four built.

- HP.94 Hastings C4

- VIP transport version for four VIPs and staff, four built.

- HP.67 Hastings T5

- Eight C1s converted for RAF Bomber Command with ventral radome to train V bomber crews on the Navigation Bombing System (NBS).

Operators

- Royal Air Force.

- No. 24 Squadron RAF

- No. 36 Squadron RAF

- No. 47 Squadron RAF

- No. 48 Squadron RAF

- No. 51 Squadron RAF

- No. 53 Squadron RAF

- No. 59 Squadron RAF

- No. 70 Squadron RAF

- No. 97 Squadron RAF

- No. 99 Squadron RAF

- No. 114 Squadron RAF

- No. 115 Squadron RAF

- No. 116 Squadron RAF

- No. 151 Squadron RAF

- No. 202 Squadron RAF

- No. 242 Squadron RAF

- No. 297 Squadron RAF

- No. 511 Squadron RAF

- Far East Communication Squadron RAF

- Middle East Communication Squadron RAF

- No.230 Operational Conversion Unit RAF

- No.240 Operational Conversion Unit RAF

- No.241 Operational Conversion Unit RAF

- Bomber Command Bombing School RAF

- Strike Command Bombing School RAF

- Central Signals Establishment RAF

- Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment.

- Royal Aircraft Establishment.

- Meteorological Research Flight

Surviving aircraft

Four Hastings are preserved in the UK and Germany:

- TG503 (T5) on display at the Alliiertenmuseum (Allied Museum), Berlin, Germany. The Hastings on display here was a participant in the Berlin Airlift.[20]

- TG511 (T5) on display in the National Cold War Exhibition at the RAF Museum Cosford, England.[13]

- TG517 (T5) on display at the Newark Air Museum, Newark, England.[21]

- TG528 (C1A) on display at the Imperial War Museum, Duxford, England.[22]

- NZ5801 (C.3) 1952. Nose/Cockpit section only of RNZAF military transport is preserved at Auckland, New Zealand's Museum of Transport and Technology along with engines, props and an undercarriage assembly, which is functional for display purposes.[6]

Accidents and incidents

- 16 July 1949 — Hastings TG611 lost control during takeoff at Berlin-Tegel Airport and dived into the ground due to incorrect tail trim; all five crew died.[23]

- 26 September 1949 — Hastings TG499 crashed after the belly pannier detached and struck the tail mid-flight; all three crew on board died.[24]

- 20 December 1950 — Hastings TG574 lost a propeller in flight, which penetrated the fuselage and killed the co-pilot. The aircraft diverted to Benina, Libya, and attempted an emergency landing, during which it flipped onto its back. A total of five out of the seven crew were killed, but the 27 passengers (all 'slip' crews returning) survived.[25]

- 19 March 1951 — Hastings WD478 stalled on takeoff at RAF Strubby; three crew died.[26]

- 16 September 1952 — Hastings WD492 experienced a whiteout and crashed at Northice, Greenland. Three servicemen were injured during the incident, but all the crew were safely recovered by USAF Rescue at Thule.[27]

- 12 January 1953 — Hastings C1 TG602 crashed in Egypt after takeoff from RAF Fayid when both elevator and the tailplane broke away; all five crew and four passengers died.[28]

- 22 June 1953 — Hastings WJ335 stalled and crashed on takeoff at RAF Abingdon after the elevator control locks had been left engaged. All six crew died.[29]

- 23 July 1953 — Hastings TG564 crashed on landing at RAF Kai Tak with one fatality on the ground and the aircraft completely burnt out. Flight was outward bound for a casualty evacuation operation from Korea to the United Kingdom.[30]

- 2 March 1955 — Hastings WD484 stalled and crashed on takeoff at RAF Boscombe Down due to the elevator controls being locked; all four crew died.[31]

- 9 September 1955 — Hastings NZ5804 lost power on three engines due to multiple birdstrikes and crashed just after takeoff from Darwin, Australia. 25 crew and passengers survived.

- 13 September 1955 — Hastings TG584 lost control attempting to overshoot at RAF Dishforth and crashed; five died.[32][33]

- 9 April 1956 — Hastings WD483 undercarriage collapsed on landing and crashed at landing. No fatalities.

- 29 May 1959 — Hastings TG522 stalled and crashed on approach to Khartoum Airport, Sudan, after engine failure. All five crew died, 25 passengers survived.[34]

- 1 March 1960 — Hastings TG579 crash-landed in the sea 1.5 miles east of RAF Gan, Maldives, in a violent tropical storm. All six crew and 14 passengers survived.[35]

- 29 May 1961 — Hastings WD497 stalled and crashed in Singapore after an engine lost power; 13 died.[36]

- 10 October 1961 — Hastings WD498 stalled and crashed on takeoff from RAF El Adem, Libya, after the pilot's seat slid back. Seventeen of the 37 occupants died.[37]

- 17 December 1963 — Hastings C.1A TG610 engine failure during 'roller' landing at Thorney Island, Sussex. Aircraft ran into, and destroyed, a radio servicing building, killing one of the occupants and injuring four. The crew was uninjured.

- 6 July 1965 — Hastings C.1A TG577, departing from RAF Abingdon on a parachute drop, crashed at Little Baldon, Oxfordshire, with the loss of 41 lives. The cause was metal fatigue of two of the elevator bolts.[38]

- 4 May 1966 — Hastings TG575 was written off when the undercarriage collapsed landing at RAF El Adem, Libya.[39]

Specifications (Hastings C.2)

Data from Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1951–52,[40] Flight International[41]

General characteristics

- Crew: five (pilot, co-pilot, radio-operator, navigator and flight engineer)

- Capacity: ** 50 troops or

- 35 paratroops or

- 32 stretchers and 29 sitting wounded

- 20,311 lb (9,213 kg) maximum payload

- Length: 81 ft 8 in (24.89 m)

- Wingspan: 113 ft 0 in (34.44 m)

- Height: 22 ft 6 in (6.86 m)

- Wing area: 1,408 sq ft (130.8 m2)

- Aspect ratio: 9.08:1

- Airfoil: NACA 23021 at root, NACA 23007 at tip

- Empty weight: 48,472 lb (21,987 kg) (equipped, freighter)

- Max takeoff weight: 80,000 lb (36,287 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 3,172 imp gal (14,420 L; 3,809 US gal)

- Powerplant: 4 × Bristol Hercules 106 14-cylinder two-row air-cooled radial engines, 1,675 hp (1,249 kW) each

- Propellers: 4-bladed de Havilland constant speed, 13 ft 0 in (3.96 m) diameter

Performance

- Maximum speed: 348 mph (560 km/h, 302 kn) at 22,200 ft (6,800 m)

- Cruise speed: 291 mph (468 km/h, 253 kn) at 15,200 ft (4,600 m) (weak mixture)

- Range: 1,690 mi (2,720 km, 1,470 nmi) (maximum payload), 4,250 mi (3,690 nmi; 6,840 km) (maximum fuel, 7,400 lb (3,400 kg) payload)

- Service ceiling: 26,500 ft (8,100 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,030 ft/min (5.2 m/s)

- Time to altitude: 26 minutes to 26,000 ft (7,900 m)

- Take-off run to 50 ft (15 m): 1,775 yd (5,325 ft; 1,623 m)

- Landing run from 50 ft (15 m): 1,430 yd (4,290 ft; 1,310 m)

See also

Related development

Related lists

References

Citations

- ↑ Barnes 1976, p. 435.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Flight International, 15 September 1947. p. 359.

- ↑ Barnes 1976, p. 437.

- ↑ Barnes 1976, p. 440.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 "Individual History: Handley Page Hastings T.5 TG511/8554M, Museum Accession Number 85/A/09." Royal Air Force Museum Cosford, Retrieved: 21 June 2019.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Flight International, 15 September 1947. p. 361.

- ↑ Flight International, 15 September 1947. pp. 359, 361.

- 1 2 Flight International, 15 September 1947. p. 363.

- 1 2 Jackson 1989, pp. 4–5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Handley Page Hastings." Royal Air Force Museum Cosford, Retrieved: 21 June 2019.

- ↑ Thetford 1957, p. 262.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, p. 49.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, p. 51.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, p. 52.

- ↑ "The Airlift plane: The Hastings TG 503." Alliierten Museum, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "Aircraft List." Newark Air Museum, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "Handley Page Hastings C1A." Imperial War Museum, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "TG611." aviation-safety.net, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "TG499." aviation-safety.net, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "TG574." aviation-safety.net, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "WD478." aviation-safety.net, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ Wilson, Keith (2015). RAF in camera, 1950s. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. p. 89. ISBN 9781473827950.

- ↑ "TG602." aviation-safety.net, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "WJ335." aviation-safety.net, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "TG564." aviation-safety.net, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "WD484." aviation-safety.net, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ Haley, William, ed. (14 September 1955). "Five killed in air crash". The Times. No. 53325. p. 8. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ↑ Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident Handley Page Hastings C.1 TG584 Dishforth RAF Station". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ↑ "TG522." aviation-safety.net, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ Cooper, John. "Splashdown on the Equator". Britain's Small Wars. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ↑ "WD497." aviation-safety.net, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "WD498." aviation-safety.net, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "TG577." aviation-safety.net, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "TG575." aviation-safety.net, Retrieved: 23 June 2019.

- ↑ Bridgman 1951, pp. 59c–60c.

- ↑ Flight International, 15 September 1947. pp. 360-361.

Bibliography

- Barnes, C. H. Handley Page Aircraft Since 1907. London: Putnam, 1976. ISBN 0-370-00030-7.

- Barnes, C. H. Handley Page Aircraft Since 1907. London: Putnam & Company, Ltd., 1987.

- Bridgman, Leonard. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1951–52. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, Ltd, 1951.

- Clayton, Donald C. Handley Page, an Aircraft Album. Shepperton, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Ltd., 1969. ISBN 0-7110-0094-8.

- Jackson, Paul. "The Hastings...Last of a Transport Line". Air Enthusiast. Issue Forty, September–December 1989. Bromley, Kent:Tri-Service Press. pp. 1–7,47–52.

- Hall, Alan W. Handley Page Hastings (Warpaint Series no.62). Bletchley, UK: Warpaint Books, 2007.

- Senior, Tim. Hastings, Including a Brief History of the Hermes – Handley Page's Post-War Transport Aircraft. Stamford, Lincs: Dalrymple & Verdun, 2008.

- "The Handley Page Hastings: Britain's largest and fastest military transport." Flight International, 15 September 1947. pp. 359–363.

- Thetford, Owen. Aircraft of the Royal Air Force 1918–57. London: Putnam, First edition 1957.

- The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft (Part Work 1982–1985). Orbis Publishing.