| Hawaiian crow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Corvidae |

| Genus: | Corvus |

| Species: | C. hawaiiensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Corvus hawaiiensis Peale, 1849 | |

| |

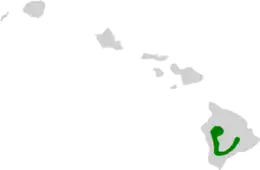

| Corvus hawaiiensis was previously endemic to Hawaiʻi | |

The Hawaiian crow or ʻalalā (Corvus hawaiiensis) is a species of bird in the crow family, Corvidae, that is currently extinct in the wild, though reintroduction programs are underway. It is about the size of the carrion crow at 48–50 cm (19–20 in) in length,[3] but with more rounded wings and a much thicker bill. It has soft, brownish-black plumage and long, bristly throat feathers; the feet, legs, and bill are black. Today, the Hawaiian crow is considered the most endangered of the family Corvidae.[4] They are recorded to have lived up to 18 years in the wild, and 28 years in captivity. Some Native Hawaiians consider the Hawaiian crow an ʻaumakua (family god).[5]

The species is known for its strong flying ability and resourcefulness, and the reasons for its various extirpations are not fully understood. It is thought that introduced diseases, such as Toxoplasma gondii, avian malaria (Plasmodium relictum), and fowlpox, were probably significant factors in the species' decline.[6]

Distribution and habitat

Before the Hawaiian crow became extinct in the wild, the species was found only in the western and southeastern parts of Hawaii. It inhabited dry and mesic forests on the slopes of Mauna Loa and Hualālai at elevations of 3,000 to 6,000 feet.[7] Ōhiʻa lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha) and koa (Acacia koa) were important tree species in its wild habitat. Extensive understory cover was necessary to protect the ʻalalā from predation by the Hawaiian hawk, or ʻio (Buteo solitarius). Nesting sites of the ʻalalā received 600–2,500 millimetres (24–98 in) of annual rainfall.[8] Fossil remains indicate that the Hawaiian crow used to be relatively abundant on all the main islands of Hawaii, along with four other now-extinct crow species.[9]

The Hawaiian crow was also preyed on by rats and the small Asian mongooses (Urva auropunctata). Feral cats that introduced Toxoplasma gondii to the birds can also prey on chicks that are unable to fly. As of 2012, the Hawaiian crow's current population is 114 birds, the vast majority of which are in Hawaiian reserves.[10]

Behavior

Diet

The omnivorous Hawaiian crow is a generalist species, eating various foods as they become available. The main portion of their diet and 50% of their feeding activity is spent foraging on trunks, branches, and foliage for invertebrates such as isopods, land snails, and arachnids. They feed in a woodpecker fashion, flaking bark and moss from trunks or branches to expose hidden insects, foraging mostly on ohia and koa, the tallest and most dominant trees in their habitats. Fruits are the second most dominant component in the Hawaiian crow's diet. The crows often collect kepau and olapa fruit clusters. Although hoawa and alani fruits have hard outer coverings, crows continue to exert energy prying them open. Passerine Nestlings and eggs are consumed most frequently in April and May, during their breeding season. Other prey include red-billed leiothrix, Japanese white-eye, Hawaiʻi ʻamakihi, ʻIʻiwi, ‘elepaio, and ʻapapane. The ʻalalā also commonly forages on flowers, especially from February through May. Nectar to feed the young is obtained from the ohia flower, oha kepau, and purple poka during the nestling period. Crows also foraged various plant parts, including the flower petals of kolea, koa, and mamane. The palila is the only other Hawaiian bird known to eat flower petals. The ʻalalā only occasionally forages on the ground, but only for a limited amount of time for risk of predators.[3]

Tool use

Captive individuals can use sticks as tools to extract food from holes drilled in logs. The juveniles exhibit tool use without training or social learning from adults, and it is believed to be a species-wide ability.[11][12][13]

Voice

The Hawaiian crow has a call described variously as a two-toned caw and as a screech with lower tones added, similar to a cat's meow. In flight, this species has been known to produce a wide variety of calls including a repeated kerruk, kerruk sound and a loud kraa-a-a-ik sound. It also makes a ca-wk sound, has a complex, burbling song, and makes a variety of other sounds as well.[9]

This is a medley of the different calls the Hawaiian Crow makes.[14]

Breeding and reproduction

Female crows are considered sexually mature at about 2 or 3 years of age and males at 4 years.[15] The Hawaiian crow's breeding season lasts from March to July; it builds a nest in March or April, lays eggs in mid-to-late April, and the eggs hatch in mid-May. Both sexes construct nests with branches from the native ohi’a tree strengthened with grasses. The crow typically lays one to five eggs (that are greenish-blue in color) per season, although at most only two will survive past the fledgling phase.[16] Only the females incubate the 2–5 eggs for 19–22 days and brood the young, of which only 1–2 fledge about 40 days after hatching. If the first clutch is lost, the pair will re-lay, which serves to be helpful in captive breeding efforts. Juveniles rely on their parents for 8 months and will stay with the family group until the next breeding season.[9]

Environmental role

The ʻalalā was one of the largest native bird populations in Hawaii. Its disappearance in the wild has had cascading effects on the environment, especially with the seed dispersal of the native plants. Many of these plants rely on the ʻalalā not only for seed dispersal but also for seed germination as seeds are passed through the crow's digestive system. Without seed dispersal, the plants have no means of growing another generation. The ʻalalā plays a key role in the maintenance of many indigenous plant species, which now could become a rarity in Hawaii's ecosystems, specifically the dry forests, without their main seed disperser.[17] The Hawaiian crow has become known as an indicator species; the disappearance of the ʻalalā indicates serious environmental problems.[18]

Primary threats

The Hawaiian crow faces an ample number of threats in the wild, which are considered contributing factors to their extinction in the wild. Small population size makes the species more vulnerable to environmental fluctuations; this leads to a higher likelihood of inbreeding, which reduces the likelihood that offspring will survive to recruitment.[19] Unlike most crows, Hawaiian crows did not adapt well to human presence. Persecution by humans is another threat to their survival, as farmers have shot ʻalalā because they were believed to disturb crops. Illegal hunting has continued even after legal protection was granted to the crows. Humans have also caused habitat degradation and deforestation through agriculture, ranching, logging, and non-native ungulates. Loss of canopy cover exposes the ʻalalā to dangerous predators. Chicks are vulnerable to tree-climbing rats and, after they leave their nests, to cats, dogs, and mongooses.[20] Deforestation also increases soil erosion and the spread of invasive plants and mosquitoes.[9] This directly relates to the primary cause of the Hawaiian crow's extinction, disease.

Avian malaria

Avian malaria is a parasitic disease of birds, caused by Plasmodium relictum, a protist affecting birds in all parts of the world. Usually this disease does not kill birds, however in an isolated habitat such as Hawaii, birds have lost evolutionary resistance and are unable to defend against the novel protist. Its main vector is the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus, introduced to the Hawaiian islands in 1826. This introduction can be attributed to birds club that brought nonnative species to replace birds that fell victim to the Avipoxvirus. At least 100 introductions have been documented in this manner.

Status and conservation

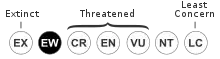

The Hawaiian crow is the most endangered corvid species in the world and the only species left in Hawaii. Like other critically endangered species, harming the Hawaiian crow is illegal under U.S. federal law. By 1994, the population dwindled to 31 individuals; 8 to 12 were wild and 19 held in captivity.[4] The last two known wild individuals of the Hawaiian crow disappeared in 2002,[21] and the species is now classified as Extinct in the Wild by the IUCN Red List.[1] While some 115 individuals remain (as of August 2014)[22] in two captive breeding facilities operated by the San Diego Zoo, attempts to reintroduce captive-bred birds into the wild have been hampered by predation by the Hawaiian hawk (Buteo solitarius), which itself is listed as Near Threatened. Breeding efforts have also been complicated due to extensive inbreeding during the crow's population decline.[23]

Protection

The ʻalalā has been legally protected by the state of Hawaii since 1931 and was recognized as federally endangered in 1967. Sites on the slopes of Mauna Loa and other natural ranges have been set aside for habitat reconstruction and native bird recovery since the 1990s. The Kūlani Keauhou area has been ranked the best spot for the crows, parts of which have been fenced and ungulate-free for 20 years, helping tremendously for habitat recovery.[9]

Reintroduction

Restoration programs for the Hawaiian crow require collaboration from private landowners, National Biological Service (NBS) biologists, US Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) biologists, and the State of Hawaii. In 1993 and 1994, 17 eggs were removed from wild nests and transported to a temporary hatcher in Kona District, Hawaii. Puppets mimicking adult crows were used to feed chicks to minimize the possibility of abnormal imprinting or human socialization. Three of the removed eggs were infertile, 13 chicks hatched, and 12 ʻalalā were successfully reared. One egg failed to hatch because of embryonic malpositioning, and another chick died from yolk-sac infection.[24]

In December 2016, five juvenile male Hawaiian crows were released into the Pu'u Maka'ala Natural Area Reserve on the Big Island, marking the first time the birds had been present in the wild since 2002.[25] However, within a week of reintroduction, three of the five birds were found dead.[26] Two of the deaths were caused by the Hawaiian hawk, and the other death was due to starvation.[26] The remaining two crows were taken out of the wild.

On September 26, 2017, 6 crows were released into the Pu'u Maka'ala Reserve. In contrast to the previous release, the group released was made of 4 males and 2 females rather than just males.[27] On October 11, 2017, another group of 5 crows, 3 males and 2 females, was also released into the area. The first group introduced also formed social groups similar to those expected of the species, and also responded to stressors in the environment, showing awareness of surroundings.[28] As of 2018, they have been described as "thriving", though they may have been negatively affected by the 2018 lower Puna eruption, which impacted at least a third of the Malama Kī Forest Reserve, an important habitat for the Hawaiian crow and other endangered Hawaiian wildlife.[29][30] Following the success of the previous year's introduction, another 5 were reintroduced to the Pu'u Maka'ala Reserve on September 25, 2018.[31] In late 2018, one of the crows released in 2017, a male named Maka'ala, was found dead due to wounds likely from a predatory attack followed by scavenging.[32]

In May 2019, two of the released crows, Mana’olana and Manaiakalani, were spotted building a nest with the female incubating eggs, marking the first wild breeding attempt made by Hawaiian crows since the extinction of the species in the wild. However, the eggs never hatched and were later presumed to be infertile, although occasionally laying infertile eggs is not uncommon for the species.[33]

By October 2020, all of the released birds except five had died from more predation by the Hawaiian hawk or other predators, or became lost in winter storms. The five remaining individuals were brought back to captivity.[34]

The reintroduction project is considering Maui as a potential location for future efforts. It is considered to be a safer area, as Hawaiian hawks are not found on Maui. While the crows were never present there in recent history, subfossil findings show that they, or a similar species, once lived on the island.[35]

Captive breeding efforts

In attempt to save the ʻalalā, efforts have been made to breed the species in captivity. Initially, a majority of these efforts proved to be highly unsuccessful. Studies have shown that females are the primary nest builders, and if the male hangs around the nest for too long and attempts to sit in it, the female either ceases her efforts to complete the nest or in other cases, builds up aggression between the breeding pair. This disruptive behavior can inhibit the production of eggs. On average, clutch size bred in captivity is much lower than it has been observed in the wild. This can be attributed to thin eggshells as a result from inbreeding, and behavioral complications from males. Bred in isolation, some males exhibit aggressive behavior towards their mates and an inability to understand friendly gestures. For the best breeding success, it is important for cages to mimic real environmental behavior, and socially-reared males are put together with the females.[36] Once these issues were realized, captive breeding has achieved much higher success; the captive population increased from 24 in 1999 to more than 100 in 2012.[37]

Conservation plans

On April 16, 2009, The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced a five-year plan to spend more than $14 million to prevent the extinction of the Hawaiian crow through protection of habitats and management of threats to the species.[38]

Cultural significance

The Hawaiian crow is a significant symbol in Hawaiian mythology. It is said to lead souls to their final resting place on the cliffs of Ka Lae, the southernmost tip on the Big Island of Hawaii. Native priests named the ʻalalā so during prayer and chants due to its distinctive call.[39]

References

- 1 2 "Corvus hawaiiensis: Bird Life International". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. 2016. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22706052A94048187.en.

- ↑ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0".

- 1 2 Sakai, Howard F.; Ralph, C. John; Jenkins, C. D. (1986-05-01). "Foraging Ecology of the Hawaiian Crow, an Endangered Generalist". The Condor. 88 (2): 211–219. doi:10.2307/1368918. JSTOR 1368918.

- 1 2 "Hawaiian crow photo – Corvus hawaiiensis – G117026". www.arkive.org. Wildscreen Arkive. Archived from the original on 2015-11-20. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ↑ Banko, Paul C.; Ball, Donna L.; Banko, Winston E. (2002). "Hawaiian Crow (Corvus hawaiiensis)". In Poole, A. (ed.). The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- ↑ Mitchell, Christen; Ogura, Christine; Meadows, Dwayne; Kane, Austin; Strommer, Laurie; Fretz, Scott; Leonard, David; McClung, Andrew (October 1, 2005). "7: Species of Greatest Conservation Need" (PDF). Hawaii's Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (Report). Honolulu, Hawaiʻi: Department of Land and Natural Resources. p. c.189. Retrieved 2009-03-20., 16 MB file. Pages are largely unnumbered but entry for "ʻAlalā or Hawaiian Crow" is roughly on page 189.

- ↑ "'Alalā – Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ↑ Draft Revised Recovery Plan for the ʻAlalā (Corvus hawaiiensis) (PDF) (Report). United States Fish and Wildlife Service. October 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Hawaiian Bird Conservation Action Plan – Hawaiian Crow". Pacific Rim Conservation (pdf). 2013. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ↑ "Alala – The Hawaiian Crow | BirdNote". birdnote.org. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ↑ Graef, A. (September 16, 2016). "Scientists discover tool use in brilliant Hawaiian crow". Care2. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ↑ Rutz, C.; et al. (2016). "Discovery of species-wide tool use in the Hawaiian crow" (PDF). Nature. 537 (7620): 403–407. Bibcode:2016Natur.537..403R. doi:10.1038/nature19103. hdl:10023/10465. PMID 27629645. S2CID 205250218.

- ↑ "Tropical crow species is highly skilled tool user" (Press release). Phys.org. 2016-09-14. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Endangered Species". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ↑ "NatureServe Explorer: Species Name Criteria – All Species – Scientific or Informal Taxonomy, Species – Informal Names." NatureServe Explorer: Species Name Criteria – All Species – Scientific or Informal Taxonomy, Species – Informal Names. NatureServe. Web. 29 Oct. 2015.

- ↑ "Comprehensive Report Species -". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ↑ Culliney, Susan; Pejchar, Liba; Switzer, Richard; Ruiz-Gutierrez, Viviana (2012-09-01). "Seed dispersal by a captive corvid: the role of the 'Alalā (Corvus hawaiiensis) in shaping Hawai'i's plant communities". Ecological Applications. 22 (6): 1718–1732. doi:10.1890/11-1613.1. JSTOR 41722888. PMID 23092010. S2CID 23240239.

- ↑ Holden, Constance (1992-05-22). "Random Samples". Science. New Series. 256 (5060): 1136–1137. Bibcode:1992Sci...256.1136H. doi:10.1126/science.256.5060.1136. JSTOR 2877246. S2CID 241636345.

- ↑ Flanagan, Alison M.; Masuda, Bryce; Grueber, Catherine E.; Sutton, Jolene T. (August 2021). "Moving from trends to benchmarks by using regression tree analysis to find inbreeding thresholds in a critically endangered bird". Conservation Biology. 35 (4): 1278–1287. Bibcode:2021ConBi..35.1278F. doi:10.1111/cobi.13650. ISSN 0888-8892. PMID 33025666. S2CID 222182269.

- ↑ "'Alalā – Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ↑ Walters, Mark Jerome (October–December 2006). "Do No Harm". Conservation Magazine. Society for Conservation Biology. 7 (4): 28–34. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ↑ KFMB-TV (August 9, 2014). "Hawaiian crow breeding season a success". Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- ↑ "Hawaiian Crow (Corvus hawaiiensis) – BirdLife species factsheet". www.birdlife.org. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ↑ Kuehler, C.; Harrity, P.; Lieberman, A.; Kuhn, M. (1995-10-01). "Reintroduction of hand-reared alala Corvus hawaiiensis in Hawaii" (PDF). Oryx. 29 (4): 261–266. doi:10.1017/S0030605300021256. S2CID 85436504. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-19.

- ↑ "VIDEO: Hawaiian Crow Released After Going Extinct In The Wild". Big Island Video News. December 16, 2016.

- 1 2 Ashe, Ivy (March 18, 2017). "Experts work to improve alala's chances after release deaths". West Hawaii Today. Archived from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ "'Alalā Released Into Natural Area Reserve". Aliso Laguna News. 2017-09-27. Retrieved 2017-10-01.

- ↑ Ako, Diane. "Rare Hawaiian crows released into native forests of Hawai'i Island". Archived from the original on 2018-06-29. Retrieved 2017-11-06.

- ↑ "'Alalā released on Hawaii Island in 2017 appear to thrive". Hawaii 24/7. 2018-04-17. Retrieved 2018-05-02.

- ↑ "Malama Kī Forest Reserve Impacted by Eruption". Big Island Now | Malama Kī Forest Reserve Impacted by Eruption. Retrieved 2018-06-29.

- ↑ "5 more alala released into wild - West Hawaii Today". www.westhawaiitoday.com. Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2018-09-29.

- ↑ "Released Hawaiian Crow Found Dead In Forest". www.bigislandvideonews.com. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- ↑ WRAL (2019-05-22). "Attempt to breed Hawaiian crows at nature reserve fails". WRAL.com. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- ↑ "The Hawaiian Crow Is Once Again Extinct in the Wild". Audubon. October 16, 2020.

- ↑ "Recovery Effort Looks to Maui as Next Step for Future of the Hawaiian Crow". Maui Now. 2 April 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ↑ Harvey, Nancy C.; Farabaugh, Susan M.; Druker, Bill B. (2002-01-01). "Effects of early rearing experience on adult behavior and nesting in captive Hawaiian crows (Corvus hawaiiensis)". Zoo Biology. 21 (1): 59–75. doi:10.1002/zoo.10024.

- ↑ "Focal Species: Hawaiian Crow or 'Alalā (Corvus hawaiiensis)" (PDF). Pacific Rim Conservation: Hawaiian Bird Conservation Action Plan. 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ↑ "$14M Effort Announced to Save Rare Hawaiian Bird". Science, Global edition. The New York Times. AP. April 17, 2009. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑ Walters, Mark Jerome (2006). Seeking the Sacred Raven: Politics and Extinction On a Hawaiian Island. Island Press/Shearwater Books. ISBN 9781610911078.