Hendrick Andriessen, known as Mancken Heyn ('Limping Henry')[1] (Antwerp, 1607 – Antwerp or Zeeland, 1655) was a Flemish still-life painter. He is known for his vanitas still lifes, which are made up of objects referencing the precariousness of life, and 'smoker' still lifes (the so-called 'toebackjes'), which depict smoking utensils. The artist worked in Antwerp and likely also in the Dutch Republic.[2]

Life

Very little is known about the artist's life and career.[3] Hendrick Andriessen was born in Antwerp where he was baptized on 23 October 1607.[2] He was known as Mancken Heyn (Limping Henry), which indicates that he must have suffered from some physical defect.[4]

It is believed he was the Hendrick Andrisen who was registered as a 'leerjongen' (apprentice) in the Guild of Saint Luke of Antwerp in the guild year 1637-1638. It is not recorded in the Guild's register with which master he apprenticed.[2][5]

On stylistic grounds it is assumed that the artist spent time in the Northern Netherlands (the Dutch Republic), possibly in the Zeeland area.[3] The place of his death is not known with certainty. It was traditionally believed that he died in Zeeland.[4] However, some art historians believe that there is a connection between Andriessen and the still life painter Pieter van der Willigen who was active in Antwerp. In particular, the same attributes occur in signed works of the two artists. It is possible that van der Willigen took over Andriessen's studio after his death in 1655. This would mean that Andriessen was living in Antwerp at the time he died. Many paintings formerly attributed to Pieter van der Willigen are now given to Andriessen.[2]

Work

Andriessen was a specialist still-life painter. His still-life paintings fall generally into the category of vanitas paintings. He further painted a number of 'smoker' still lifes (the so-called 'toebackjes'), which depict smoking paraphernalia.[2] Only a few works of the artist are known. The number of works currently attributed to Andriessen range from six to nine of which five are said to be signed. Andriessen signed his paintings variously using his full signature, his initials or monogram.[3]

Attributions of work to him are sometimes disputed. An example is the Vanitas with a skull and a Moorish boy holding a portrait of the painter (c. 1650, Johnson Museum of Art), which is attributed to David Bailly on the museum website but is attributed to Andriessen by Fred G. Meijer (1985).[6][7] A Vanitas still life with a skull, a broken 'Roemer', a rose, an hour glass, a nautilus shell, a pocket watch and other objects, all on a draped table (At Christie's on 25–26 November 2014, Amsterdam, lot 79) is attributed by Fred G. Meijer (1996) to 'anonymous Antwerp 1630-1640' while Dr. Sam Segal has identified it as a characteristic example of Andriessen's work.[8][9]

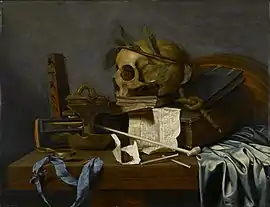

Most of Andriessen's known oeuvre falls into the category of vanitas still lifes. This genre of still life offers a reflection on the meaninglessness of earthly life and the transient nature of all earthly goods and pursuits. This meaning is conveyed in these still lifes through the use of stock symbols, which reference the transience of things and, in particular, the futility of earthly wealth: a skull, soap bubbles, candles, empty glasses, wilting flowers, insects, smoke, watches, mirrors, books, hourglasses and musical instruments, various expensive or exclusive objects such as jewellery and rare shells. The term vanitas is derived from the famous line 'Vanitas, Vanitas. Et omnia Vanitas', in the book of the Ecclesiastes in the bible, which in the King James Version is translated as "Vanity of vanities, all is vanity".[10][11] The worldview behind the vanitas paintings was a Christian understanding of the world as a temporary place of fleeting pleasures and sorrows from which mankind could only escape through the sacrifice and resurrection of Christ. While most of these symbols reference earthly existence (books, scientific instruments, etc.) or the transience of life and death (skulls, soap bubbles) some symbols used in the vanitas paintings carry a dual meaning: the rose refers as much to the brevity of life as it is a symbol of the resurrection of Christ and thus eternal life.[12] This duality of meaning is shown in Hendrick Andriessen's Vanitas still life of a skull, a vase of flowers and smoking implements in a niche (c. 1635–1650, Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent) which shows a rose just rising above a skull in its role as a resurrection flower.[13] Most of Andriessen's vanitas still lifes include a skull as one of the key props.[12]

One of Andriessen's best-known works is the Vanitas still life with a globe, sceptre, a skull crowned with straw (c. 1650, Mount Holyoke College Art Museum). Because of the presence in the still life of a skull, a crown and sceptre and other related objects it is regarded as a reference to the death by decapitation of King Charles I of England.[14] The objects in this vanitas still life not only convey the usual moral lessons of vanitas still lifes but also reference the fate of the executed English king. The composition blends the genres of still life, portraiture and history painting. Andriessen placed on the edge of the table in the painting a letter supposedly written by Death itself telling the viewer how the fate of Charles I exemplified the futility of the pursuit of wealth and power. The leering skull in the still life is almost like a portrait of the dead King, which confronts the viewer with its riveting stare. To the left of the skull are placed the stock symbols of transience such as wilting flowers, bubbles, an extinguished taper and a luxurious pocket watch waiting to be wound. To the right of the skull Andriessen depicted the symbols of Charles' royal power such as the gold crown, the Order of the Garter and the gold sceptre. The artist included a self-portrait on the silver candlestick. It is possible that Andriessen produced this particular work while living in the Dutch Republic. In the Northern Netherlands there was a lot of sympathy for the executed king among the large community of exiled English Royalists and a significant number of Dutch citizens. The painting was clearly intended for an erudite patron who would have been able to appreciate its many obscure references and symbolism and complex political and philosophical message.[3] Other Flemish still life artists were also producing vanitas still lifes on the death of King Charles I for the Dutch market. An example is the Vanitas still life with a poem on the death of Charles I by Godfriedt van Bochoutt (signed and dated 1668, at Bonhams auction of 23 October 2019, London lot 67TP.[15]

In an exceptional example of collaboration between artists in Antwerp, Nicolaes van Verendael added in 1679 flowers to the skull and smoking implements painted by Hendrick Andriessen in the 1640s to create the Vanitas still life with a bunch of flowers, a candle, smoking implements and a skull (Gallerie dell'Accademia of Venice).[16]

Hendrick Andriessen was one of the Antwerp painters who collaborated on a Cabinet of Pictures (Royal Collection, England) by Jacob de Formentrou. This painting dated between 1654 and 1659 represents an art gallery with works of important Antwerp masters and can be regarded as a carefully crafted advertisement for the contemporary talent and past legacy of the Antwerp school of painting. The inclusion in the art gallery's collection of a work by Hendrick Andriessen depicting a vanitas still life (bottom left on the right-hand wall, monogrammed HA) shows that he was at the time considered to be a leading painter in Antwerp.[17]

References

- ↑ Also known as: Manke Heyn Andriesz,; Variant name spellings: Hendrik Andriessen, Hendric Andriessen, Hendrick Andriesz, Hendrick Andriessens, Hendrick Andriesz., Hendrick Andrisen

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hendrick Andriessen at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- 1 2 3 4 N.S. Baadj, Hendrick Andriesen's 'portrait' of King Charles I, in: The Burlington Magazine 151 (2009), pp. 22–27

- 1 2 Cornelis De Bie, Het gulden Cabinet vande edel vry schilder const, inhoudende den lof vande vermarste schilders, architecte, beldthowers ende plaetsnyders van dese eeuw, Jan Meyssens, 1661, p. 176 (in Dutch)

- ↑ De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche sint Lucasgilde Volume 2, by Ph. Rombouts and Th. van Lerius, Antwerp, Julius de Koninck, 1871, p. 93, on Google books (in Dutch)

- ↑ David Bailly, Vanitas at Johnson Museum of Art

- ↑ Hendrick Andriessen, Vanitasstilleven op een ronde tafel met een schedel, bloemen, een luit, een palet met penselen, boeken, rookgerei, horloge, zonnewijzer, blokfluit, brief, zandloper, kandelaar, zeepbellen en rechts een moorse jongen met een portretje van de schilder in zijn hand at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- ↑ Anoniem Antwerpen jaren 1630/40, Vanitasstilleven met schedel, roos en roemer, jaren 1630/40 at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- ↑ Hendrik Andriessen, Vanitas-Stillleben mit einem Römerglas, einer Rose und einem Schädel at Koller (Zürich) on 14–19 September 2015, lot 3039 (in German)

- ↑ Ratcliffe, Susan (13 October 2011). Oxford Treasury of Sayings and Quotations. Oxford: OUP. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-199-60912-3.

- ↑ Delahunty, Andrew (23 October 2008). From Bonbon to Cha-cha. Oxford Dictionary of Foreign Words and Phrases. Oxford: OUP. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-199-54369-4.

- 1 2 Kristine Koozin, The Vanitas Still Lifes of Harmen Steenwyck: Metaphoric Realism, Edwin Mellen Press, 1990, p. vi-vii

- ↑ Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., From botany to bouquets: flowers in Northern art, Catalogue of an exhibition held in 1999 in Washington (National Gallery of Art), Washington (National Gallery of Art), 1999, pp. 67 and 80

- ↑ Hendrick Andriessen, Vanitas Still Life, ca. 1650 at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum

- ↑ Godfriedt van Bochoutt Vanitas still life with a poem concerning the death of Charles I, record at the Netherlands Institute for Art History

- ↑ Hendrick Andriessen en Nicolaes van Verendael, Vanitasstilleven met bosje bloemen, kandelaar, rookgerei en een schedel at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- ↑ Nadia Sera Baadj, Monstrous creatures and diverse strange things": The Curious Art of Jan van Kessel the Elder (1626–1679), A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History of Art) in The University of Michigan, 2012

External links

Media related to Hendrick Andriessen at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hendrick Andriessen at Wikimedia Commons