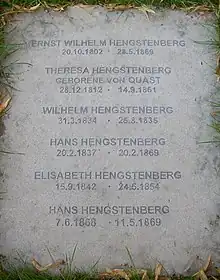

Ernst Wilhelm Theodor Herrmann Hengstenberg (20 October 1802, in Fröndenberg – 28 May 1869, in Berlin), was a German Lutheran churchman and neo-Lutheran theologian from an old and important Dortmund family.

He was born at Fröndenberg, a Westphalian town, and was educated by his father Johann Heinrich Karl Hengstenberg, who was a famous minister of the Reformed Church and head of the Fröndenberg convent of canonesses (Fräuleinstift). His mother was Wilhelmine then Bergh. Entering the University of Bonn in 1819, Hengstenberg attended the lectures of Georg Wilhelm Freytag for Oriental languages and of Johann Karl Ludwig Gieseler for church history, but his energies were principally devoted to philosophy and philology, and his earliest publication was an edition of the Arabic Mu'allaqat of Imru' al-Qais, which gained for him a prize at his graduation in the philosophical faculty. This was followed in 1824 by a German translation of Aristotle's Metaphysics.[1]

Finding himself without the means to complete his theological studies under Johann August Wilhelm Neander and Friedrich August Tholuck in Berlin, he accepted a post at Basel as tutor in Oriental languages to Johann Jakob Stähelin (1797–1875), later a professor at the university. It was there that he began to direct his attention to a study of the Bible, which led him to a conviction, not only of the divine character of evangelical religion, but also of the unapproachable adequacy of its expression in the Augsburg Confession. In 1824 he joined the philosophical faculty of the University of Berlin as a privatdozent, and in 1825 he became a licentiate in theology, his theses being remarkable for their evangelical fervour and for their emphatic protest against every form of "rationalism", especially in questions of Old Testament criticism.[1]

In 1826 he became professor extraordinarius in theology; and in July 1827 took on the editorship of the Evangelische Kirchenzeitung, a strictly orthodox journal, which in his hands acquired an almost unique reputation as a controversial organ. It did not become well known until in 1830 an anonymous article (by Ernst Ludwig von Gerlach) appeared, which openly charged Wilhelm Gesenius and Julius Wegscheider with infidelity and profanity, and on the ground of these accusations advocated the interposition of the civil power, thus giving rise to the prolonged Hallischer Streit. In 1828 the first volume of Hengstenberg's Christologie des Alten Testaments passed through the press; in the autumn of that year he became professor ordinarius in theology, and in 1829 doctor of theology.[1]

Main works

- Christologie des Alten Testaments (1829–1835; 2nd ed., 1854–1857; Eng. trans. by R Keith, 1835–1839, also in Clark's Foreign Theological Library, by T Meyer and J Martin, 1854–1858), a work of much learning the estimate of which varies according to the hermeneutical principle of the individual critic.

- English translation in (Google Books)

- Beiträge zur Einleitung in das Alte Testament (1831–1839); Eng. trans., Dissertations on the Genuineness of Daniel, and the Integrity of Zechariah (Edin., 1848), and Dissertation on the Genuineness of the Pentateuch (Edin., 1847), in which the traditional view on each question is strongly upheld, and much capital is made of the absence of harmony among the negative.

- English translation in (Google Books for Vol. 1) (Google Books for Vol. 2)

- English translation in (Internet Archive)

- Die Bücher Moses und Aegypten (1841).

- English translation in (Internet Archive)

- Die Geschichte Bileams u. seiner Weissagungen (1842; translated along with the Dissertations on Daniel and Zechariah).

- Commentar über die Psalmen (1842–1847; 2nd ed., 1849–1852; Eng. trans. by P Fairbain and J Thomson, Edin., 1844–1848), which shares the merit and defects of the Christologie.

- English translation in (Internet Archive for Vol. 1) (Internet Archive for Vol. 2) (Internet Archive for Vol. 3)

- Die Offenbarung Johannis erläutert (1849–1851; 2nd ed., 1861–1862; Eng. trans. by P. Fairbairn also in Clark's " Foreign Theological Library," 1851–1852)

- English translation in (Internet Archive for Vol. 1) (Internet Archive for Vol. 2).

- Das Hohelied Salomonis ausgelegt (1853).

- Der Prediger Salomo ausgelegt (1859).

- English translation in (Internet Archive)

- Das Evangelium Johannis erläutert (1861–1863; 2nd ed., 1867–1871 English translation, 1865).

- Die Weissagungen das Propheten Ezechiel erläutert (1867–1868).

- English translation in (Google Books)

Of minor importance are:

- De rebus Tyrioruz commentatio academica (1832).

- Uber den Tag des Herrn (1852).

- Da Passe, ein Vortrag (1853).

- Die Opfer der heiligen Schrift (1859).

Several series of papers also, as, for example:

- "The Retentio of the Apocrypha".

- "Freemasonry" (1854).

- "Duelling" (1856).

- "The Relation between the Jews and the Christian Church" (1857; 2nd ed., 1859), which originally appeared in the Kirchenzeitung, were afterwards printed in a separate form.

Posthumously published:

- Geschichte des Reiches Gottes unter dem Alten Bunde (1869–1871).

- Das Buch Hiob erläutert (1870–1875).

- Vorlesungen über die Leidensgeschichte.

Notes

- 1 2 3 Chisholm 1911.

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hengstenberg, Ernst Wilhelm". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 269.

- Martin Gerhardt (fortgeführt von Alfred Adam): Friedrich von Bodelschwingh. Ein Lebensbild aus der deutschen Kirchengeschichte. 1. Bd. 1950, 2. Bd. 1. Hälfte 1952, 2. Hälfte 1958.

- Joachim Mehlhausen: Artikel Hengstenberg, Ernst Wilhelm. In: TRE 15, S. 39–42.

- Otto von Ranke (1880), "Hengstenberg, Ernst Wilhelm", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 11, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 737–747

- Karl Kupisch (1969), "Hengstenberg, Wilhelm", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 8, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 522–523; (full text online)

- Hans Wulfmeyer: Ernst Wilhelm Hengstenberg als Konfessionalist. Erlangen 1970.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz (1990). "Hengstenberg, Ernst Wilhelm". In Bautz, Friedrich Wilhelm (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). Vol. 2. Hamm: Bautz. cols. 713–714. ISBN 3-88309-032-8.

- Helge Dvorak: Biographisches Lexikon der Deutschen Burschenschaft. Band I: Politiker, Teilband 2: F–H. Heidelberg 1999, S. 297.

External links

- Literature by and about Ernst Wilhelm Hengstenberg in the German National Library catalogue

- Works by Ernst Wilhelm Hengstenberg at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ernst Wilhelm Hengstenberg at Internet Archive

- Hengstenberg and His Influence on German Protestantism The Methodist Review 1862, vol. XLIV, p. 108