High-energy X-rays or HEX-rays are very hard X-rays, with typical energies of 80–1000 keV (1 MeV), about one order of magnitude higher than conventional X-rays used for X-ray crystallography (and well into gamma-ray energies over 120 keV). They are produced at modern synchrotron radiation sources such as the beamlines ID15 and BM18 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF). The main benefit is the deep penetration into matter which makes them a probe for thick samples in physics and materials science and permits an in-air sample environment and operation. Scattering angles are small and diffraction directed forward allows for simple detector setups.

High energy (megavolt) X-rays are also used in cancer therapy, using beams generated by linear accelerators to suppress tumors.[1]

Advantages

High-energy X-rays (HEX-rays) between 100 and 300 keV bear unique advantage over conventional hard X-rays, which lie in the range of 5–20 keV [2] They can be listed as follows:

- High penetration into materials due to a strongly reduced photo absorption cross section. The photo-absorption strongly depends on the atomic number of the material and the X-ray energy. Several centimeter thick volumes can be accessed in steel and millimeters in lead containing samples.

- No radiation damage of the sample, which can pin incommensurations or destroy the chemical compound to be analyzed.

- The Ewald sphere has a curvature ten times smaller than in the low energy case and allows whole regions to be mapped in a reciprocal lattice, similar to electron diffraction.

- Access to diffuse scattering. This is absorption and not extinction limited at low energies while volume enhancement takes place at high energies. Complete 3D maps over several Brillouin zones can be easily obtained.

- High momentum transfers are naturally accessible due to the high momentum of the incident wave. This is of particular importance for studies of liquid, amorphous and nanocrystalline materials as well as pair distribution function analysis.

- Realization of the Materials oscilloscope.

- Simple diffraction setups due to operation in air.

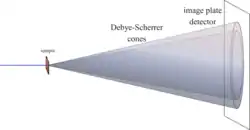

- Diffraction in forward direction for easy registration with a 2D detector. Forward scattering and penetration make sample environments easy and straight forward.

- Negligible polarization effects due to relative small scattering angles.

- Special non-resonant magnetic scattering.

- LLL interferometry.

- Access to high-energy spectroscopic levels, both electronic and nuclear.

- Neutron-like, but complementary studies combined with high precision spatial resolution.

- Cross sections for Compton scattering are similar to coherent scattering or absorption cross sections.

Applications

With these advantages, HEX-rays can be applied for a wide range of investigations. An overview, which is far from complete:

- Structural investigations of real materials, such as metals, ceramics, and liquids. In particular, in-situ studies of phase transitions at elevated temperatures up to the melt of any metal. Phase transitions, recovery, chemical segregation, recrystallization, twinning and domain formation are a few aspects to follow in a single experiment.

- Materials in chemical or operation environments, such as electrodes in batteries, fuel cells, high-temperature reactors, electrolytes etc. The penetration and a well-collimated pencil beam allows focusing in the region and material of interest while it undergoes a chemical reaction.

- Study of 'thick' layers, such as oxidation of steel in its production and rolling process, which are too thick for classical reflectometry experiments. Interfaces and layers in complicated environments, such as the intermetallic reaction of Zincalume surface coating on industrial steel in the liquid bath.

- In situ studies of industrial like strip casting processes for light metals. A casting setup can be set up on a beamline and probed with the HEX-ray beam in real time.

- Bulk studies in single crystals differ from studies in surface-near regions limited by the penetration of conventional X-rays. It has been found and confirmed in almost all studies, that critical scattering and correlation lengths are strongly affected by this effect.

- Combination of neutron and HEX-ray investigations on the same sample, such as contrast variations due to the different scattering lengths.

- Residual stress analysis in the bulk with unique spatial resolution in centimeter thick samples; in-situ under realistic load conditions.

- In-situ studies of thermo-mechanical deformation processes such as forging, rolling, and extrusion of metals.

- Real time texture measurements in the bulk during a deformation, phase transition or annealing, such as in metal processing.

- Structures and textures of geological samples which may contain heavy elements and are thick.

- High resolution triple crystal diffraction for the investigation of single crystals with all the advantages of high penetration and studies from the bulk.

- Compton spectroscopy for the investigation of momentum distribution of the valence electron shells.

- Imaging and tomography with high energies. Dedicated sources can be strong enough to obtain 3D tomograms in a few seconds. Combination of imaging and diffraction is possible due to simple geometries. For example, tomography combined with residual stress measurement or structural analysis.

See also

References

- ↑ Graham A. Colditz, The SAGE Encyclopedia of Cancer and Society, SAGE Publications, 2015, ISBN 1483345742 page 1329

- 1 2 Liss KD, Bartels A, Schreyer A, Clemens H (2003). "High energy X-rays: A tool for advanced bulk investigations in materials science and physics". Textures Microstruct. 35 (3/4): 219–52. doi:10.1080/07303300310001634952.

Further reading

- Liss, Klaus-Dieter; Bartels, Arno; Schreyer, Andreas; Clemens, Helmut (2003). "High-Energy X-Rays: A tool for Advanced Bulk Investigations in Materials Science and Physics". Textures and Microstructures. 35 (3–4): 219–252. doi:10.1080/07303300310001634952.

- Benmore, C. J. (2012). "A Review of High-Energy X-Ray Diffraction from Glasses and Liquids". ISRN Materials Science. 2012: 1–19. doi:10.5402/2012/852905.

- Eberhard Haug; Werner Nakel (2004). The elementary process of Bremsstrahlung. World Scientific Lecture Notes in Physics. Vol. 73. River Edge, NJ: World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-238-578-9.

External links

- Liss, Klaus-Dieter; et al. (2006). "Recrystallization and phase transitions in a γ-Ti Al-based alloy as observed by ex situ and in situ high-energy X-ray diffraction". Acta Materialia. 54 (14): 3721–3735. Bibcode:2006AcMat..54.3721L. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2006.04.004.