_(geograph_5107013).jpg.webp)

The Highgate Wood telephone exchange was the first all-electronic telephone exchange in Britain. It was built in the London suburb of Highgate by members from Joint Electronic Research Council (JERC).[lower-alpha 1]

Introduction

On Wednesday 12 December 1962, the 800 line Highgate Wood exchange was accepted by the Postmaster General, Mr. Reginald Bevins, MP, on behalf of the Post Office, from the five manufacturers who had helped to build it, the first all-electronic telephone exchange in Britain and one of the first in the world to go into public service. It had already carried public traffic experimentally for brief periods during the previous few weeks. He also announced on that day the building of three more advanced electronic exchanges to be installed and in operation within the next two years at Goring-on-Thames (high speed TDM 100 channel), Pembury (low-speed TDM 30 channel), and at Leighton Buzzard. The only one that was completed was the TXE1 at Leighton Buzzard, the other two being quickly abandoned.

The Highgate Wood Electronic Exchange had been the result of six years co-operative research and development between the Post Office and five principal British manufacturers of exchange equipment. This was coordinated through the Joint Electronic Research Committee (JERC). Although different contractors had been responsible for the system design, installation and manufacturing of various sections of the exchange, the commissioning had been the work of teams drawn from each of the parties to the agreement. The Highgate Wood Exchange was not entirely typical of the systems which were to follow it. Each of the three new exchanges, all of which were to operate completely on their own, with no standby exchange as was the case at Highgate Wood, were to be designed to try out actual service conditions. Two of them were based on slightly different applications of the time-division pulse-amplitude modulation (TDM) principle, and the third, at Leighton Buzzard, on space-division switching. All three were to be fully transistorised so that they were going to be more compact than Highgate Wood (which had about 5,000 transistors and 500 valves) and would have needed less power. They were also expected to show a significant improvement in reliability that had been a problem at Highgate Wood. The model of Highgate Wood had worked "reasonably satisfactorily" [see Harris 2001] in the laboratory but the analogue transmission was too noisy on the long cable runs in an actual exchange. The problem was thought to be the earthing arrangements. TDM exchange operation in the UK did not become possible until pulse-code modulation (PCM) was developed, providing a digital transmission solution which led to System X.

The trial at Highgate Wood was unsuccessful. Roy Harris states that it carried mainly artificial traffic and was looked after on a care and maintenance basis until it was taken out of service in 1965.[1] The Connected Earth website calls Highgate Wood a "magnificent failure".[2] For the UK it meant that an intermediate approach which would extend the usefulness Strowger switch technology would be needed. This led to the implementation of reed relay and crossbar technologies alongside Strowger extensions until the arrival of digital SPC exchanges in the mid-80s.[3]

Exchange design

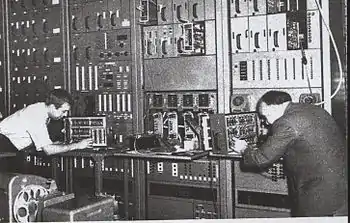

One of the JERC's first decisions was to build an electronic exchange using the "Switched Highways" system, which employed time division multiplex techniques (TDM), while at the same time continuing research on alternative solutions to the problem of electronic switching. The "Switched Highways" system was invented by L.R.F Harris at Dollis Hill in 1952. It was also decided that the experimental equipment should provide the full service and maintenance facilities of a comparable electro-mechanical exchange. At the same time, the techniques used had to be demonstrably capable of serving the largest existing exchanges. Moreover, the experiment was to be conducted in an exchange giving public service and therefore fully interconnected with the public network. This meant that it would need conversion equipment to enable it to inter-work with the existing system and to use the existing subscribers' apparatus and line plant. For these reasons the Highgate Wood installation was bigger than the small number of lines would have seemed to warrant and about 400,000 electronic components were fitted. Much of the control equipment could have served an exchange of about 7,000 lines. The exchange used both valves and transistors. There were approximately 5,000 transistors and 500 valves. The valves were used in the more crucial areas, as the transistors of the day were not up to the required performance.

Switching and trunking

The most novel part of the conception of the exchange design was the use of pulse-amplitude modulation and time division multiplex techniques for the transmission of up to one hundred conversations over a common channel, which was well ahead of its time. This technique would eventually be used in System X and other digital exchanges as technology caught up. Another interesting feature of the installation was the use of time-sharing in the setting-up of the calls and in their control, which was something that all subsequent digital exchange design would follow.

At the time in Strowger exchanges ranks of selectors were interconnected by means of a complex trunking system dictated by the method of setting up the calls and by the need to economise in the total number of switching points. The trunking of the Switched Highways system was simple because each switch could carry one hundred simultaneous conversations, the lines were concentrated into large groups before being connected to the switches; and the calls were set up by a high-speed common control apparatus operating quickly enough to deal with the calls on a "one at a time" basis.

In the trunking of Highgate Wood the system, the lines (subscribers) and junctions were arranged in groups, the size of each group depending on the traffic. There were up to 800 lines in a group. Each group was connected to a "highway" over which 100 multiplexed conversations could be carried, each conversation using a one-microsecond time slot or channel time at a repetition frequency of 10 kHz. The "highways" were fully interconnected by electronic switches or gates and gates also connected the "highways" to the common control. Each line in the electronic system was provided with gates, which enable it to be connected to its "highway".

Scanning

To set up a call the line gates and the "highway" switch gates were set so that for the duration of the call they would open at the channel time allotted to the conversation. The gates connecting the lines to the "highways" would, of course, be closed at all other times but the inter-highway gates, which might be switching many calls, would operate at the pulse channel times of all the conversations in progress on their "highways". Delay line stores controlled all the gates.

Common control

The high speeds of electronic equipment allowed the use of a single common control to deal with even the largest and most heavily loaded exchange and made possible the use of the "one at a time" principle in the setting up of connections. The control contained "logical" elements which controlled the sequences, and "memory" elements to store information relating to the switches and calls and permanent and semi-permanent information relating to the lines. These were basic requirements in any type of telephone exchange. In electromechanical exchanges the call memories are spread over the equipment in the form of mechanical spring sets and operated relays while the line information is stored in the form of jumpers on the IDF.

The first task of the electronic control was to detect when a new call arrived. For this purpose each subscriber's line termination was examined for a period of 280 microseconds every 224 milliseconds, a process known as scanning. Junctions were scanned at eight times this rate. The scanning was carried out by a magnetic drum, each track of which is divided into 100 sections or words, one for each line. Parallel tracks were used for each 100 lines, one track providing the permanent (IDF) information (that is, directory number and class of service), another track gave a semi-permanent information (that is, whether the line was already engaged or parked because of PG conditions). Since the tracks are switched in sequence the information relating to each line could be read sequentially as the drum rotated, the angular position of the word together with the track number defining the equipment position that is, the line apparatus number of the line being scanned. The groups of 800 lines (junctions and subscribers) at Highgate Wood were divided into eight sub-groups, one sub-group for each track of the drum. In each sub-group the line units was arranged in ten columns of ten rows so that any line position could be defined by a ZXY code, Z for the sub-group, X for the column and Y for the rows.

To avoid the use of a separate delay line store for every line termination it was convenient to use, in each group of 800 lines, three sets of five stores coded to correspond with the ZXY designation of the line. As the drum rotated it generated waveforms corresponding to the ZXY code of the line whose information was available at that time. These waveforms indicated the appropriate delay lines and if a call was to be set up a selected pulse was injected into the selected delay lines which caused them to open the line gates repeatedly at the selected pulse time, the pulse continuing to circulate until the connection was cleared.

The common control of the system was divided into two parts. The first was the equipment to store and process the information relating to the setting up and the progress of the calls (the stores used in this part of the equipment were 900 microsecond magnetostriction delay lines). The second was the permanent memory containing the translators and so on, which used the magnetic drum store. In addition, various services, such as the waveform generator and the "clock pulse" generator used to time the system, were provided.

During the progress of a call the setting-up apparatus first connected the caller to a register equipment and later connected the caller to their correspondent by way of the "highway" switch, a channel selector choosing a free channel suitable for the call, that was, one available to both subscribers.

The register equipment received the dialled digits and could process and store 100 nine digit numbers. This capacity was not fully exploited at Highgate Wood although the register and most of the control equipment was potentially capable of dealing with the traffic from a large metropolitan exchange.

Supervisory

The supervisory equipment monitored the set-up connections and, in addition, controlled the application of tones (for example, dial tone), and applied ringing, metering, and release conditions. It monitored the lines by scanning the "highways" successively, examining each pulse channel for a period of one microsecond. In this period the state of the call was registered and, depending on the stage reached by the call and the class of service of the lines concerned, the logical circuits in the equipment decide on the action to be taken, that was, whether ringing should be applied or cut-off or whether the call should be released. Both the register and the supervisory equipment had "persistence timers" which, in effect, substituted the B and C relays and the S and Z pulses of the Strowger system. These timers were also provided on a common basis.

The system provided for four-wire transmission, within the exchange, it was continuously self-routined and all common equipment was duplicated, the spare equipment being switched-in automatically if the routiners detected faults on the worker. The equipment was experimental and experimental verification of the various equipment practices and maintenance aids was perhaps the most important feature of the field trial.

Interworking

The exchange had been designed to work as a director exchange in the existing director network, and no attempt had been made to introduce new service facilities. This meant that conversion equipment had to be interpolated between the electronic exchange and the outside world and the exchange had to be adapted to suit subscribers' apparatus and designed to work with mechanical equipment.

Notes

- ↑ The JERC was formed in 1956 and consisted of:

the British Post Office (GPO)

Siemens Brothers & Co. (soon to be part of AEI)

Automatic Telephone & Electric Co. Ltd AT&E (soon to be part of Plessey)

Ericsson Telephones Ltd.

General Electric Co. GEC

Standard Telephones & Cables Ltd. (STC)

References

- ↑ Harris, R. (2001). Electronic Telephone Exchanges in the UK: Early Research & Development 1947 - 1963. Journal of the IBTE , Volume 2 (Part 4), Pages 31 - 38

- ↑ "Connected Earth: An electronic future : generation two ..." Archived from the original on 22 March 2011.

- ↑ Harris, R. (2002). Electronic Switching in the UK: Research & Development 1960 - 1968. Journal of the IBTE , Volume 3 (Part 1), Pages 37 - 45

- Broadhurst, S.W., "The Highgate Wood Electronic Telephone Exchange", The Post Office Electrical Engineers' Journal (POEEJ) January 1963 (Vol.55 part 4) pp. 265–274. The article's bibliography cites eight other references dated 1956–1960.

- Professor J. E. Flood for further information on Highgate Wood.

- 100 Years of Telephone Switching (1878-1978).: Electronics, computers, and ... By Robert J. Chapuis, Amos E. Joel pp. 61–63