| Aesculus hippocastanum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Botanical illustration (1885) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Sapindaceae |

| Genus: | Aesculus |

| Species: | A. hippocastanum |

| Binomial name | |

| Aesculus hippocastanum | |

Aesculus hippocastanum, the horse chestnut,[1][2][3] is a species of flowering plant in the maple, soapberry and lychee family Sapindaceae. It is a large, deciduous, synoecious (hermaphroditic-flowered) tree.[4] It is also called horse-chestnut,[5] European horsechestnut,[6] buckeye,[7] and conker tree.[8] It is not to be confused with the Spanish chestnut, Castanea sativa, which is a tree in another family, Fagaceae.[9]: 371

Description

Aesculus hippocastanum is a large tree, growing to about 39 metres (128 ft) tall[9] with a domed crown of stout branches. On old trees, the outer branches are often pendulous with curled-up tips. The leaves are opposite and palmately compound, with 5–7 leaflets 13–30 cm (5–12 in) long, making the whole leaf up to 60 cm (24 in) across, with a 7–20 cm (3–8 in) petiole. The leaf scars left on twigs after the leaves have fallen have a distinctive horseshoe shape, complete with seven "nails". The flowers are usually white with a yellow to pink blotch at the base of the petals;[9] they are produced in spring in erect panicles 10–30 cm (4–12 in) tall with about 20–50 flowers on each panicle. Its pollen is not poisonous for honey bees.[10] Usually only 1–5 fruits develop on each panicle. The shell is a green, spiky capsule containing one (rarely two or three) nut-like seeds called conkers or horse-chestnuts. Each conker is 2–4 cm (3⁄4–1+1⁄2 in) in diameter, glossy nut-brown with a whitish scar at the base.[11]

Etymology

The common name horse chestnut originates from the similarity of the leaves and fruits to sweet chestnuts, Castanea sativa (a tree in a different family, the Fagaceae),[9] together with the alleged observation that the fruit or seeds could help panting or coughing horses.[12][13]

Although it is sometimes known as buckeye,[7] for the resemblance of the seed to a deer's eye, the term buckeye is more commonly used for New World members of the genus Aesculus.[14]

Distribution and habitat

The native distribution of Aesculus hippocastanum given by different sources varies. As of March 2023, Plants of the World Online considered it to be native to the Balkans (Albania, Bulgaria, Greece and former Yugoslavia), but also to Turkey and Turkmenistan.[15] A 2017 assessment for the IUCN Red List restricted the native distribution to the Balkan area: Albania, Bulgaria, mainland Greece and North Macedonia.[1] It has been introduced and planted around the world. It can be found in many parts of Europe as far north as Harstad north of the Arctic Circle in Norway,[16] and Gästrikland in Sweden as well as in many parks and cities around the northern United States and Canada such as Edmonton in Canada.[17]

The compact native population of horse chestnut in Bulgaria is distinct from the horse chestnut forests of northern Greece, western North Macedonia and Albania. It is limited to an area of 9 ha in the Preslav Mountain north of the Balkan Mountains, in the valleys of the Dervishka and Lazarska rivers. Bulgaria's relict horse chestnut forests are critically endangered at the national level and protected as part of the Dervisha Managed Nature Reserve.[18]

Uses

It is widely cultivated in streets and parks throughout the temperate world, and has been particularly successful in places like Ireland, Great Britain and New Zealand, where they are commonly found in parks, streets and avenues. Cultivation for its spectacular spring flowers is successful in a wide range of temperate climatic conditions provided summers are not too hot, with trees being grown as far north as Edmonton, Alberta, Canada,[19] the Faroe Islands,[20] Reykjavík, Iceland and Harstad, Norway.

In Britain and Ireland, the seeds are used for the popular children's game conkers. During the First World War, there was a campaign to ask for everyone (including children) to collect the seeds and donate them to the government. The conkers were used as a source of starch for fermentation using the Clostridium acetobutylicum method devised by Chaim Weizmann to produce acetone for use as a solvent for the production of cordite, which was then used in military armaments. Weizmann's process could use any source of starch, but the government chose to ask for conkers to avoid causing starvation by depleting food sources. But conkers were found to be a poor source, and the factory only produced acetone for three months; however, they were collected again in the Second World War for the same reason.[21] In the US state of Ohio, the seeds of the related Aesculus glabra are called 'buckeyes' and give rise to one of the state's symbols and nicknames, the Buckeye State.[22]

The seeds, especially those that are young and fresh, are slightly poisonous, containing alkaloid saponins and glucosides. Although not dangerous to touch, they cause sickness when eaten; consumed by horses, they can cause tremors and lack of coordination.[23]

The horse-chestnut is a favourite subject for bonsai.[24]

Though the seeds are said to repel spiders there is little evidence to support these claims. The presence of saponin may repel insects but it is not clear whether this is effective on spiders.[25]

Aesculus hippocastanum is affected by the leaf-mining moth Cameraria ohridella, whose larvae feed on horse chestnut leaves. The moth was described from North Macedonia where the species was discovered in 1984 but took 18 years to reach Britain.[26]

In Germany, they are commonly planted in beer gardens, particularly in Bavaria. Prior to the advent of mechanical refrigeration, brewers would dig cellars for lagering. To further protect the cellars from the summer heat, they would plant horse chestnut trees, which have spreading, dense canopies but shallow roots which would not intrude on the caverns. The practice of serving beer at these sites evolved into the modern beer garden.[27]

An inexpensive detergent for washing clothes can be made at home from conkers, and this is said to be an environmentally benign ('eco-friendly') detergent.[28]

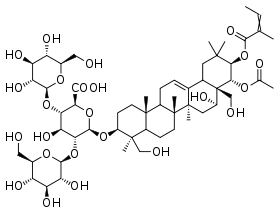

Traditional medicine

The seed extract standardized to around 20 percent aescin (escin) is possibly useful in traditional medicine for its effect on venous tone.[29][30] A Cochrane Review suggested that horse chestnut seed extract may be an efficacious and safe short-term treatment for chronic venous insufficiency, but definitive randomized controlled trials had not been conducted to confirm the efficacy.[31]

Safety

There is risk of acute kidney injury, "when patients, who had undergone cardiac surgery were given high doses of horse chestnut extract i.v. for postoperative oedema. The phenomenon was dose dependent as no alteration in kidney function was recorded with 340 μg/kg, mild kidney function impairment developed with 360 μg/kg and acute kidney injury with 510 μg/kg".[32]

Raw horse chestnut seed, leaf, bark and flower are toxic due to the presence of aesculin and should not be ingested. Horse chestnut seed is classified by the FDA as an unsafe herb.[33] The glycoside and saponin constituents are considered toxic.[33]

Other chemicals

Quercetin 3,4'-diglucoside, a flavonol glycoside can also be found in horse chestnut seeds.[34] Leucocyanidin, leucodelphinidin and procyanidin A2 can also be found in horse chestnut.

Anne Frank tree

A fine specimen of the horse-chestnut was the Anne Frank tree in the centre of Amsterdam, which she mentioned in her diary and which survived until August 2010, when a heavy wind blew it over.[35][36] Eleven young specimens, sprouted from seeds from this tree, were transported to the United States. After a long quarantine in Indianapolis, each tree was shipped off to a new home at a notable museum or institution in the United States, such as the 9/11 Memorial Park, Central H.S. in Little Rock, and two Holocaust Centers. One of them was planted outdoors in March 2013 in front of the Children's Museum of Indianapolis, where they were originally quarantined.[37]

Symbol of Kyiv

The horse chestnut tree is one of the symbols of Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine.[38]

Diseases

_in_Parma%252C_Italy.jpg.webp)

- Bleeding canker. Half of all horse-chestnuts in Great Britain are now showing symptoms to some degree of this potentially lethal bacterial infection.[39][40]

- Guignardia leaf blotch, caused by the fungus Guignardia aesculi

- Wood rotting fungi, e.g. such as Armillaria and Ganoderma

- Horse chestnut scale, caused by the insect Pulvinaria regalis

- Horse-chestnut leaf miner, Cameraria ohridella, a leaf mining moth.[41] The larvae of this moth species bore through the leaves of the horse chestnut, causing premature colour changes and leaf loss.[40]

- Phytophthora bleeding canker, a fungal infection.[42]

Gallery

Planted as a feature tree in a park

Planted as a feature tree in a park Leaves and trunk

Leaves and trunk Foliage and flowers

Foliage and flowers Close-up of flowers

Close-up of flowers Trunk

Trunk Germination on lawn

Germination on lawn

Other sources

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Leach, M (2001). "Aesculus hippocastanum". Australian Journal of Medical Herbalism. 13 (4).

- "Castanea sativa (European chestnut, Spanish Chestnut, Sweet chestnut) | North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox". plants.ces.ncsu.edu. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "Horse Chestnut | Winchester Hospital". www.winchesterhospital.org. Archived from the original on 2021-06-05. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "Horse Chestnut | Index of Herbs". indexofherbs.com. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

References

- 1 2 3 Allen, D.J.; Khela, S. (2017). "Horse Chestnut, Aesculus hippocastanum" [errata version published in 2018]. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2017: e.T202914A122961065. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS (n.d.). "Aesculus hippocastanum". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ↑ Brouillet L, Desmet P, Coursol F, Meades SJ, Favreau M, Anions M, Bélisle P, Gendreau C, Shorthouse D, et al. "Aesculus hippocastanum Linnaeus". data.canadensys.net. Database of Vascular Plants of Canada (VASCAN). Archived from the original on 2018-02-17. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ↑ "Aesculus hippocastanum: Reproduction". Archived from the original on 2015-01-30.

- ↑ BSBI List 2007 (xls). Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Archived from the original (xls) on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ↑ "Aesculus hippocastanum (Common Horsechestnut, European Horsechestnut, Horsechestnut) | North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox". plants.ces.ncsu.edu. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- 1 2 "Horse Chestnut". NCCIH.

- ↑ Coles, Jeremy. "Why we love conkers and horse chestnut trees". BBC Earth. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Stace, C. A. (2010). New Flora of the British Isles (Third ed.). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521707725.

- ↑ "Bee Trees - Horse Chestnut | Beespoke Info". beespoke.info.

- ↑ Rushforth, K. (1999). Trees of Britain and Europe. Collins ISBN 0-00-220013-9.

- ↑ Lack, H. Walter. "The Discovery and Rediscovery of the Horse Chestnut" (PDF). Arnoldia. 61 (4). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-27.

- ↑ Little, Elbert L. (1994) [1980]. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Trees: Western Region (Chanticleer Press ed.). Knopf. p. 541. ISBN 0394507614.

- ↑ Wott, John A. "The Many Faces of Aesculus" (PDF). Washington Park Arboretum Bulletin.

- ↑ "Aesculus hippocastanum L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- ↑ "Hestekastanje".

- ↑ "Holowach Tree".

- ↑ "Forests of Horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum) :: Red Data Book of Bulgaria". e-ecodb.bas.bg. Retrieved 2023-02-10.

- ↑ Edmonton

- ↑ Højgaard, A., Jóhansen, J., & Ødum, S. (1989). A century of tree planting on the Faroe Islands. Ann. Soc. Sci. Faeroensis Supplementum 14.

- ↑ "Conkers - collected for use in two world wars". Making history. BBC. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ↑ "Ohio State Nickname | The Buckeye State". statesymbolsusa.org. 5 September 2014. Retrieved 2021-09-08.

- ↑ Lewis, Lon D. (1995). Feeding and care of the horse. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780683049671. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ D'Cruz, Mark. "Ma-Ke Bonsai Care Guide for Aesculus hippocastanum". Ma-Ke Bonsai. Archived from the original on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- ↑ Edwards, Jon (2010). "Spiders vs conkers: the definitive guide". Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 2013-09-06. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ↑ Lees, D.C.; Lopez-Vaamonde, C.; Augustin, S. 2009. Taxon page for Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dimic 1986. In: EOLspecies, http://www.eol.org/pages/306084. First Created: 2009-06-22T13:47:37Z. Last Updated: 2009-08-10T12:57:23Z.

- ↑ Schäffer, Albert (2012-05-21). "120 Minuten sind nicht genug" [120 minutes aren't enough]. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 2016-10-11.

- ↑ "How to Make Laundry Detergent from Conkers (Horse Chestnuts)".

- ↑ Diehm, C.; Trampisch, H. J.; Lange, S.; Schmidt, C. (1996). "Comparison of leg compression stocking and oral horse-chestnut seed extract therapy in patients with chronic venous insufficiency". Lancet. 347 (8997): 292–4. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90467-5. PMID 8569363. S2CID 20408233.

- ↑ "Horse chestnut". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. 1 October 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ↑ Pittler MH, Ernst E. (2012). "Horse chestnut seed extract for chronic venous insufficiency". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11 (11): CD003230. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003230.pub4. PMC 7144685. PMID 23152216.

- ↑ Parfitt, Kathleen (1999). Martindale: The complete drug reference.: Das komplette Arzneimittelverzeichnis. pp. 1543–4. ISBN 085369429X.

- 1 2 "Horse chestnut". Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. 29 March 2022. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ↑ Wagner, J. (1961). "Quercetin-3,4?-diglukosid, ein Flavonolglykosid des Roßkastaniensamens". Die Naturwissenschaften. 48 (2): 54. Bibcode:1961NW.....48Q..54W. doi:10.1007/BF00603428. S2CID 29060667.

- ↑ Sterling, Toby (24 August 2010). "Anne Frank's 'beautiful' tree felled by Amsterdam storm". The Scotsman. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Gray-Block, Aaron (23 August 2010). "Anne Frank tree falls over in heavy wind, rain". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 August 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Pamela Engel (24 March 2013). "Saplings from Anne Frank's tree take root in US". Retrieved 26 July 2018 – via Yahoo News.

- ↑ "Thujoy Khreshchatyk". Why Kyivans miss chestnuts and how they became a symbol of the capital, Ukrayinska Pravda (29 May 2019) (in Ukrainian)

- ↑ "Extent of the bleeding canker of horse chestnut problem". UK Forestry Commission. Archived from the original on 2009-12-09. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- 1 2 "Horse chestnut pest and disease problems". www.suffolkcoastal.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 23 September 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ↑ "Other common pest and disease problems of horse chestnut". UK Forestry Commission. Archived from the original on 2009-12-09. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ↑ "Bleeding Canker". Royal Horticultural Society. 11 November 2009. Archived from the original on 16 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-09.