First combined edition (publ. Ted Smart, 2000) | |

| Author | Philip Pullman |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy novel |

| Publisher | Scholastic |

| Published | 1995–2000 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

His Dark Materials is a trilogy of fantasy novels by Philip Pullman consisting of Northern Lights (1995; published as The Golden Compass in North America), The Subtle Knife (1997), and The Amber Spyglass (2000). It follows the coming of age of two children, Lyra Belacqua and Will Parry, as they wander through a series of parallel universes. The novels have won a number of awards, including the Carnegie Medal in 1995 for Northern Lights and the 2001 Whitbread Book of the Year for The Amber Spyglass. In 2003, the trilogy was ranked third on the BBC's The Big Read poll.[1]

Although His Dark Materials has been marketed as young adult fiction, and the central characters are children, Pullman wrote with no target audience in mind. The fantasy elements include witches and armoured polar bears; the trilogy also alludes to concepts from physics, philosophy, and theology. It functions in part as a retelling and inversion of John Milton's epic Paradise Lost,[2] with Pullman commending humanity for what Milton saw as its most tragic failing, original sin.[3] The trilogy has attracted controversy for its criticism of religion.

The London Royal National Theatre staged a two-part adaptation of the trilogy in 2003–2004. New Line Cinema released a film adaptation of Northern Lights, The Golden Compass, in 2007. A HBO/BBC television series based on the novels was broadcast between November 2019 and February 2023.[4][5]

Pullman followed the trilogy with three novellas set in the Northern Lights universe: Lyra's Oxford (2003), Once Upon a Time in the North (2008), and Serpentine (2020). La Belle Sauvage, the first book in a new trilogy titled The Book of Dust, was published on 19 October 2017; the second book of the new trilogy, The Secret Commonwealth, was published in October 2019. Both are set in the same universe as Northern Lights.

Setting

The trilogy takes place across a multiverse, moving between many parallel worlds. In Northern Lights, the story takes place in a world with some similarities to our own: dress-style resembles that of the UK's Edwardian era; the technology does not include cars or fixed-wing aircraft, but zeppelins feature as a mode of transport.

The dominant religion has parallels with Christianity.[6] The Church (governed by the "Magisterium", the same name as the authority of the Catholic Church) exerts a strong control over society and has some of the appearance and organisation of the Catholic Church, but one in which the centre of power had been moved from Rome to Geneva, moved there by Pullman's fictional "Pope John Calvin" (Geneva was the home of the historical John Calvin).[7]

In The Subtle Knife, the story moves between our own world, the world of the first novel, and a third world containing the city of Cittàgazze. In The Amber Spyglass, several other worlds appear alongside those three.

Titles

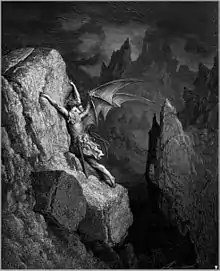

The title of the series comes from 17th-century poet John Milton's Paradise Lost:[8]

Into this wilde Abyss,

The Womb of nature and perhaps her Grave,

Of neither Sea, nor Shore, nor Air, nor Fire,

But all these in their pregnant causes mixt

Confus'dly, and which thus must ever fight,

Unless th' Almighty Maker them ordain

His dark materials to create more Worlds,

Into this wilde Abyss the warie fiend

Stood on the brink of Hell and look'd a while,

Pondering his Voyage; for no narrow frith

He had to cross.— Paradise Lost, Book 2, lines 910–920

Pullman chose this particular phrase from Milton because it echoed the dark matter of astrophysics.[9]

Pullman earlier proposed to name the series The Golden Compasses, also a reference to Paradise Lost,[10] where they denote God's circle-drawing instrument used to establish and set the bounds of all creation:

_British_Museum.jpg.webp) |

|

| God as architect, wielding the golden compasses, by William Blake (left) and Jesus as geometer in a 13th-century medieval illuminated manuscript. | |

Then staid the fervid wheels, and in his hand

He took the golden compasses, prepared

In God's eternal store, to circumscribe

This universe, and all created things:

One foot he centred, and the other turned

Round through the vast profundity obscure...— Paradise Lost, Book 7, lines 224–229

Despite the confusion with the other common meaning of compass (the navigational instrument), The Golden Compass became the title of the American edition of Northern Lights (the book features an "alethiometer", a rare truth-telling device that one might describe as a "golden compass").

Plot

Northern Lights (or The Golden Compass)

In Jordan College, Oxford, 11-year-old Lyra Belacqua and her dæmon Pantalaimon witness the Master attempt to poison Lord Asriel, Lyra's rebellious and adventuring uncle. She warns Asriel, then spies on his lecture about Dust, mysterious elementary particles. Lyra's friend Roger is kidnapped by child abductors known as Gobblers. Lyra is adopted by a charming socialite, Mrs Coulter. The Master secretly entrusts Lyra with an alethiometer, a truth-telling device. Lyra discovers that Mrs Coulter is the leader of the Gobblers, and that it is a project secretly funded by the Church. Lyra flees to the Gyptians, canal-faring nomads, whose children have also been abducted. They reveal to Lyra that Asriel and Mrs Coulter are actually her parents.

The Gyptians form an expedition to the Arctic with Lyra to rescue the children. Lyra recruits Iorek Byrnison, an armoured bear, and his human aeronaut friend, Lee Scoresby. She also learns that Lord Asriel has been exiled, guarded by the bears on Svalbard.

Near Bolvangar, the Gobbler research station, Lyra finds an abandoned child who has been cut from his dæmon; the Gobblers are experimenting on children by severing the bond between human and dæmon, a procedure called intercision.

Lyra is captured and taken to Bolvangar, where she is reunited with Roger. Mrs Coulter tells Lyra that the intercision prevents the onset of troubling adult emotions. Lyra and the children are rescued by Scoresby, Iorek, the Gyptians, and Serafina Pekkala's flying witch clan. Lyra falls out of Scoresby's balloon and is taken by the panserbjørne to the castle of their usurping king, Iofur Raknison. She tricks Iofur into fighting Iorek, who arrives with the others to rescue Lyra. Iorek kills Iofur and takes his place as the rightful king.

Lyra, Iorek, and Roger travel to Svalbard, where Asriel has continued his Dust research in exile. He tells Lyra that the Church believes Dust is the basis of sin, and plans to visit the other universes and destroy its source. He severs Roger from his dæmon, killing him and releasing enough energy to create an opening to a parallel universe. Lyra resolves to stop Asriel and discover the source of Dust for herself.

The Subtle Knife

Lyra journeys through Asriel's opening between worlds to Cittàgazze, a city whose denizens discovered a way to travel between worlds. Cittàgazze's reckless use of the technology has released Spectres which destroy adult souls but to which children are immune, rendering the world empty of adults. Here Lyra meets and befriends Will Parry, a twelve-year-old boy from our world's Oxford. Will, who recently killed a man to protect his ailing mother, has stumbled into Cittàgazze in an effort to locate his long-lost father. Venturing into Will's (our) world, Lyra meets Dr. Mary Malone, a physicist who is researching dark matter, which is analogous to Dust in Lyra's world. Lyra encourages Dr. Malone to attempt to communicate with the particles, and when she does they tell her to travel into the Cittàgazze world. Lyra's alethiometer is stolen by Lord Boreal alias Sir Charles Latrom, an ally of Mrs Coulter who has found a way to Will's Oxford and established a home there.

Will becomes the bearer of the Subtle Knife, a tool forged three hundred years before by Cittàgazze's scientists from the same alloy used to make the guillotine in Bolvangar. One edge of the knife can divide subatomic particles and form subtle divisions in space, creating portals between worlds; the other edge easily cuts through any form of matter. Using the knife's portal-creating powers, Will and Lyra are able to retrieve her alethiometer from Latrom's mansion in Will's world.

Meanwhile, in Lyra's world, Lee Scoresby seeks out the Arctic explorer Stanislaus Grumman, who years before entered Lyra's world through a portal in Alaska. Scoresby finds him living as a shaman under the name Jopari and he turns out to be Will's father, John Parry. Parry insists on being taken through the opening into the Cittàgazze world in Scoresby's balloon, since he has foreseen that he should meet the wielder of the Subtle Knife there. In that world, Scoresby dies defending Parry from the forces of the Church, while Parry succeeds in reuniting with his son moments before being murdered by Juta Kamainen, a witch whose love John had once rejected. After his father's death, Will discovers that Lyra has been kidnapped by Mrs Coulter, and he is approached by two angels requesting his aid.

The Amber Spyglass

At the beginning of The Amber Spyglass, Lyra has been kidnapped by her mother, Mrs Coulter, an agent of the Magisterium who has learned of the prophecy identifying Lyra as the next Eve. A pair of angels, Balthamos and Baruch, tell Will that he must travel with them to give the Subtle Knife to Lyra's father, Lord Asriel, as a weapon against The Authority. Will ignores the angels; with the help of a local girl named Ama, the Bear King Iorek Byrnison, and Lord Asriel's Gallivespian spies, the Chevalier Tialys and the Lady Salmakia, he rescues Lyra from the cave where her mother has hidden her from the Magisterium, which has become determined to kill her before she yields to temptation and sin like the original Eve.

Will, Lyra, Tialys and Salmakia journey to the Land of the Dead, temporarily parting with their dæmons to release the ghosts from their captivity. Mary Malone, a scientist from Will's world interested in "shadows" (or Dust in Lyra's world), travels to a land populated by strange sentient creatures called Mulefa. There, she comes to understand the true nature of Dust, which is both created by and nourishes life that has become self-aware. Lord Asriel and the reformed Mrs Coulter work to destroy the Authority's Regent Metatron. They succeed, but themselves suffer annihilation in the process by pulling Metatron into the abyss.

The Authority himself dies of his own frailty when Will and Lyra free him from the crystal prison wherein Metatron had trapped him, able to do so because an attack by cliff-ghasts kills or drives away the prison's protectors. When Will and Lyra emerge from the land of the dead, they find their dæmons.

The book ends with Will and Lyra falling in love but realising they cannot live together in the same world, because all windows – except one from the underworld to the world of the Mulefa – must be closed to prevent the loss of Dust, because with every window opening, a Spectre would be created and that means Will must never use the knife again. They must also be apart because both of them can only live full lives in their native worlds. During the return, Mary Malone learns how to see her own dæmon, who takes the form of a black Alpine chough. Lyra loses her ability to intuitively read the alethiometer and determines to learn how to use her conscious mind to achieve the same effect.

Characters

All humans in Lyra's world, including witches, have a dæmon. It is the physical manifestation of a person's 'inner being', soul or spirit. It takes the form of a creature (moth, bird, dog, monkey, snake, etc.) and is usually the opposite sex to its human counterpart. The dæmons of children have the ability to change form - from one creature to another - but during a child's puberty, their dæmon "settles" into a permanent form, which reflects the person's personality. When a person dies, the dæmon dies too. Armoured bears, cliff ghasts, and other creatures do not have dæmons. An armoured bear's armour is his soul.

- Lyra Belacqua, a wild 12-year-old girl, has grown up in the fictional Jordan College, Oxford. She prides herself on her capacity for mischief, especially her ability to lie, earning her the epithet "Silvertongue" from Iorek Byrnison. Lyra has a natural ability to use the alethiometer, which is capable of answering any question when properly manipulated and read.

- Pantalaimon is Lyra's dæmon. Like all children's dæmons, he changes form from one creature to another frequently. When Lyra reaches puberty, he assumes the permanent form of a pine marten.

- Will Parry, a sensible, morally conscious, assertive 12-year-old boy from our world. He becomes the bearer of the subtle knife. Will is independent and responsible for his age, having looked after his mentally ill mother for several years. Will's dæmon is Kirjava.

- The Authority is the first angel to have emerged from Dust. He told the later-arriving angels that he created them and the universe, but this is a lie. Although he is the overarching antagonist of the series, the Authority remains in the background; he makes his only appearance late in The Amber Spyglass. The Authority has grown weak and transferred most of his powers to his regent, Metatron.

- Lord Asriel, ostensibly Lyra's uncle, is actually her father. He opens a rift between the worlds in his pursuit of Dust. His dream of establishing a Republic of Heaven leads him to use his power to raise a grand army from across the multiverse to rise up in rebellion against the forces of the Church.

- Marisa Coulter is the beautiful and manipulative mother of Lyra, and the former lover of Lord Asriel. She serves the Church by kidnapping children for research into the nature of Dust, in the course of which she separates them from their dæmons - a procedure known as intercision. Initially hostile to Lyra, she realises that she loves her daughter and seeks to protect her from agents of the Church who want to kill Lyra. Her dæmon is a golden monkey with a cruel streak.

- Metatron, Asriel's principal adversary, was a human, Enoch, in biblical times, but was later transfigured into an angel. The Authority, his health declining, appointed Metatron his Regent. As Regent, Metatron has implanted the monotheistic religions across the universes.

- Lord Carlo Boreal - or Sir Charles Latrom, CBE, as he is known as in Will Parry's world-is a minor character in Northern Lights, but the main antagonist in The Subtle Knife. He is an old Englishman, appearing to be in his sixties.

- Mary Malone, is a physicist and former nun from Will's world. She meets Lyra during Lyra's first visit to Will's world. Lyra provides Mary with insight into the nature of Dust. Agents of the Church force Mary to flee to the world of the Mulefa. There she constructs the amber spyglass, which enables her to see the otherwise invisible Dust. Her purpose is to learn why Dust, which Mulefa civilisation depends on, is flowing out of the universe.

- Iorek Byrnison is a massive armoured bear. An armoured bear's armour is his soul. Iorek's armour is stolen, so he becomes despondent. With Lyra's help he regains his armour, his dignity, and his kingship over the armoured bears. In gratitude, and impressed by her cunning, he dubs her "Lyra Silvertongue". A powerful warrior and blacksmith, Iorek repairs the Subtle Knife when it shatters. He later goes to war against The Authority and Metatron.

- Lee Scoresby, a rangy Texan, is a balloonist. He helps Lyra in an early quest to reach Asriel's residence in the North, and he later helps John Parry reunite with his son Will.

- Serafina Pekkala is the beautiful queen of a clan of Northern witches. Her snow-goose dæmon Kaisa, like all witches' dæmons, can travel much farther apart from her than the dæmons of humans, without feeling the pain of separation.

- The Master of Jordan heads Jordan College, part of Oxford University in Lyra's world. Helped by other Jordan College employees, he is raising the supposedly orphaned Lyra. Faced with difficult choices that only later become apparent, he tries unsuccessfully to poison Lord Asriel.

- Roger Parslow is the kitchen boy at Jordan College and Lyra's best friend.

- John Parry is Will's father. He is an explorer from our world who discovered a portal to Lyra's world and became the shaman known as Stanislaus Grumman or Jopari, a variation of his original name.

- The Four Gallivespians—Lord Roke, Madame Oxentiel, Chevalier Tialys, and Lady Salmakia—are tiny people (a hand-span tall) with poisonous heel spurs.

- Ma Costa: A Gyptian woman whose son, Billy Costa, is abducted by the Gobblers. She rescues Lyra from Mrs Coulter and takes her to John Faa. Ma Costa nursed Lyra when she was a baby.

- John Faa: The King of all the Gyptians. He journeys with Lyra to the North with his companion Farder Coram. Faa and Costa rescue Lyra when she runs away from Mrs Coulter. Then they take her to Iorek Byrnison.

- Father Gomez is a priest sent by the Church to assassinate Lyra.

- Fra Pavel Rašek is an alethiometrist of the Consistorial Court of Discipline, but a sluggish reader of the device.

- Balthamos is a rebel angel who, with his lover Baruch, join in Will's journey to find the captured Lyra. Near the end of the story, he saves their lives by killing Father Gomez.

- Mulefa are four-legged wheeled animals; they have one leg in front, one in back, and one on each side. Their "wheels" are large, round, hard seed-pods from trees; an axle-like claw at the end of each leg grips a seed-pod.

Dæmons

.jpg.webp)

One distinctive aspect of Pullman's story is the presence of "dæmons" (pronounced "demon"). In the birth-universe of the story's protagonist Lyra Belacqua, a human individual's inner-self[12] manifests itself throughout life as an animal-shaped "dæmon" that almost always stays near its human counterpart. During the childhood of its associated human, a dæmon can change its animal shape at will, but with the onset of adolescence it settles into a fixed, final animal form.

Influences

Pullman has identified three major literary influences on His Dark Materials: the essay On the Marionette Theatre by Heinrich von Kleist,[13] the works of William Blake, and, most important, John Milton's Paradise Lost, from which the trilogy derives its title.[14] In his introduction, he adapts a famous description of Milton by Blake to quip that he (Pullman) "is of the Devil's party and does know it".

Critics have compared the trilogy with C. S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia, which Pullman despises,[15][16] and also with such fantasy books as Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson and A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L'Engle.[17][18]

Awards and recognition

The first volume, Northern Lights, won the Carnegie Medal for children's fiction in the UK in 1995.[19] In 2007, the judges of the CILIP Carnegie Medal for children's literature selected it as one of the ten most important children's novels of the previous 70 years. In an online June 2007 poll, it was voted the best Carnegie Medal winner in the 70-year history of the award, the Carnegie of Carnegies.[20][21] The Amber Spyglass won the 2001 Whitbread Book of the Year award, the first time that such an award has been bestowed on a book from their "children's literature" category.[22]

The trilogy came third in the 2003 BBC's Big Read, a national poll of viewers' favourite books, after The Lord of the Rings and Pride and Prejudice.[1]

On 19 May 2005, Pullman attended the British Library in London to receive formal congratulations for his work from culture secretary Tessa Jowell "on behalf of the government".[23] On 25 May 2005, Pullman received the Swedish government's Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award for children's and youth literature (sharing it with Japanese illustrator Ryōji Arai).[24] Swedes regard this prize as second only to the Nobel Prize in Literature; it has a value of 5 million Swedish Kronor or approximately £385,000. In 2008, The Observer cites Northern Lights as one of the 100 best novels.[25] Time magazine in the US included Northern Lights (The Golden Compass) in its list of the 100 Best Young-Adult Books of All Time.[26] In November 2019, the BBC listed His Dark Materials on its list of the 100 most influential novels.[27]

Christian opposition

His Dark Materials has occasioned controversy, primarily among some Christian groups.[28][29][30]

Cynthia Grenier, in the Catholic Culture, said: "In the world of Pullman, God Himself (the Authority) is a merciless tyrant. His Church is an instrument of oppression, and true heroism consists of overthrowing both".[31] William A. Donohue of the Catholic League described Pullman's trilogy as "atheism for kids".[32] Pullman said of Donohue's call for a boycott, "Why don't we trust readers? [...] Oh, it causes me to shake my head with sorrow that such nitwits could be loose in the world".[33]

In a November 2002 interview, Pullman was asked to respond to the Catholic Herald calling his books "the stuff of nightmares" and "worthy of the bonfire". He replied: "My response to that was to ask the publishers to print it in the next book, which they did! I think it's comical, it's just laughable".[34] The original remark in Catholic Herald (which was "there are numerous candidates that seem to me to be far more worthy of the bonfire than Harry Potter") was written in the context of parents in South Carolina pressing their Board of Education to ban the Harry Potter books.[35]

Pullman expressed surprise over what he considered to be a relatively low level of criticism for His Dark Materials on religious grounds, saying "I've been surprised by how little criticism I've got. Harry Potter's been taking all the flak... Meanwhile, I've been flying under the radar, saying things that are far more subversive than anything poor old Harry has said. My books are about killing God".[36] Others support this interpretation, arguing that the series, while clearly anticlerical, is also anti-theological because the death of God is represented as a fundamentally unimportant question.[37]

Pullman found support from some other Christians, most notably from Rowan Williams, the former archbishop of Canterbury (spiritual head of the Anglican Communion), who argued that Pullman's attacks focus on the constraints and dangers of dogmatism and the use of religion to oppress, not on Christianity itself.[38] Williams also recommended the His Dark Materials series of books for inclusion and discussion in Religious Education classes, and stated that "To see large school-parties in the audience of the Pullman plays at the National Theatre is vastly encouraging".[39] Pullman and Williams took part in a National Theatre platform debate a few days later to discuss myth, religious experience, and its representation in the arts.[40]

Related works

Lyra's Oxford

The 2003 novella Lyra's Oxford takes place two years after the timeline of The Amber Spyglass. A witch who seeks revenge for her son's death in the war against the Authority draws Lyra, now 15, into a trap. Birds mysteriously rescue her and Pan, and she makes the acquaintance of an alchemist, formerly the witch's lover.

Once Upon a Time in the North

This 2008 novella serves as a prequel to His Dark Materials and focuses on the Texan aeronaut Lee Scoresby as a young man. After winning his hot-air balloon, Scoresby heads to the North, landing on the Arctic island Novy Odense, where he is pulled into a conflict between the oil tycoon Larsen Manganese, the corrupt mayoral candidate Ivan Poliakov, and his longtime enemy from the Dakota Country, Pierre McConville. The story tells of Lee and Iorek's first meeting and of how they overcame these enemies.[41]

The Collectors

A short story originally released exclusively as an audiobook by Audible in December 2014, narrated by actor Bill Nighy. The story refers to the early life of Mrs Coulter and is set in the senior common room of an Oxford college.[42] The story was released by Penguin Books as a physical book in September 2022.[43]

The Book of Dust

The Book of Dust is a second trilogy of novels set before, during and after His Dark Materials. The first book, La Belle Sauvage, was published on 19 October 2017.[44] The second book, The Secret Commonwealth, was published on 3 October 2019.[45]

Serpentine

A novella that was released in October 2020. Set after the events of The Amber Spyglass and before The Secret Commonwealth, Lyra and Pantalaimon journey back to the far North to meet with the Consul of Witches.[46]

The Imagination Chamber

In January 2022, Pullman announced the release of the book The Imagination Chamber: Cosmic Rays from Lyra's Universe, which would include new scenes set during the events of His Dark Materials and The Book of Dust. It was published on 28 April 2022.[47]

Adaptations

Radio

BBC Radio 4 broadcast a radio play adaptation of His Dark Materials in 3 episodes, each lasting 2.5 hours. It was first broadcast in 2003, and re-broadcast in both 2008-9 and in 2017, and was and released by the BBC on CD and cassette. Cast included Terence Stamp as Lord Asriel and Lulu Popplewell as Lyra.[48]

Also in 2003 a radio dramatisation of Northern Lights was made by RTÉ (Irish public radio).[49]

Theatre

Nicholas Hytner directed a theatrical version of the books as a two-part, six-hour performance for London's Royal National Theatre in December 2003, running until March 2004. It starred Anna Maxwell-Martin as Lyra, Dominic Cooper as Will, Timothy Dalton as Lord Asriel, Patricia Hodge as Mrs Coulter and Niamh Cusack as Serafina Pekkala, with dæmon puppets designed by Michael Curry. The play was successful and was revived (with a different cast and a revised script) for a second run between November 2004 and April 2005. It has since been staged by several other theatres in the UK and elsewhere.

A new production was staged at Birmingham Repertory Theatre in March and April 2009, directed by Rachel Kavanaugh and Sarah Esdaile and starring Amy McAllister as Lyra. This version toured the UK and included a performance in Pullman's hometown of Oxford; Pullman made a cameo appearance.

Film

New Line Cinema released a film adaptation, titled The Golden Compass, on 7 December 2007. Directed by Chris Weitz, the production had a mixed reception, and though worldwide sales were strong, its U.S. earnings were not as high as the studio had hoped.[50]

The filmmakers obscured the explicitly Biblical character of the Authority to avoid offending viewers. Weitz declared that he would not do the same for the planned sequels. "Whereas The Golden Compass had to be introduced to the public carefully", he said, "the religious themes in the second and third books can't be minimised without destroying the spirit of these books. ...I will not be involved with any 'watering down' of books two and three, since what I have been working towards the whole time in the first film is to be able to deliver on the second and third".[51]

The Golden Compass film stars Dakota Blue Richards as Lyra, Nicole Kidman as Mrs Coulter, and Daniel Craig as Lord Asriel. Eva Green plays Serafina Pekkala, Ian McKellen voices Iorek Byrnison, and Freddie Highmore voices Pantalaimon. While Sam Elliott blamed the Catholic Church's opposition for forcing the cancellation of any adaptations of the rest of the trilogy, The Guardian's film critic Stuart Heritage believed disappointing reviews may have been the real reason.[52]

Television

In November 2015, the BBC commissioned a television adaptation of His Dark Materials.[53] The eight-part adaptation had a planned premiere date in 2017.[54] By July 2018, Dafne Keen had been provisionally cast as Lyra Belacqua, Ruth Wilson as Marisa Coulter, James McAvoy as Lord Asriel, Lin-Manuel Miranda as Lee Scoresby and Clarke Peters as the Master of Jordan College.[55] The series received its premiere in London on 15 October 2019.[55] Broadcast began on BBC One in the United Kingdom and in Ireland on 3 November and on HBO in the United States on 4 November 2019.[56] In 2020 the second series of His Dark Materials began streaming on BBC One in the United Kingdom on 8 November and on HBO Max in the United States on 16 November.[57] The third and final eight-episode series premiered first on HBO on 5 December 2022, and on 18 December 2022 in the UK.

Audiobooks

Random House produced unabridged audiobooks of each His Dark Materials novel, read by Pullman, with parts read by actors including Jo Wyatt, Steven Webb, Peter England, Stephen Thorne and Douglas Blackwell.[58]

See also

References

- 1 2 "BBC – The Big Read". BBC. April 2003. Retrieved 26 July 2019

- ↑ Robert Butler (3 December 2007). "An Interview with Philip Pullman". The Economist. Intelligent Life. Archived from the original on 5 March 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- ↑ Freitas, Donna; King, Jason Edward (2007). Killing the imposter God: Philip Pullman's spiritual imagination in His Dark Materials. San Francisco, CA: Wiley. pp. 68–9. ISBN 978-0-7879-8237-9.

- ↑ "His Dark Materials". BBC One. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ↑ "His Dark Materials". HBO. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ↑ Squires (2003: 61): "Religion in Lyra's world...has similarities to the Christianity of 'our own universe', but also crucial differences…[it] is based not in the Catholic centre of Rome, but in Geneva, Switzerland, where the centre of religious power, narrates Pullman, moved in the Middle Ages under the aegis of John Calvin".

- ↑ Northern Lights p. 31: "Ever since Pope John Calvin had moved the seat of the papacy to Geneva … the Church's power over every aspect of life had been absolute"

- ↑ Highfield, Roger (27 April 2005). "The quest for dark matter". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ↑

Dodd, Celia (8 May 2004). "Debate: Human nature: Universally acknowledged". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

He explains how the title came about: "The notion of dark matter struck me as an intensely poetic idea, that the vast bulk of the universe is made up of stuff we can't see at all and have no idea what it is. It's intoxicatingly exciting. Then, when I was looking in Paradise Lost for the title of the trilogy, I came across this marvellous phrase, 'His dark materials', which fits in so well with dark matter. So I hoped and prayed that no one would discover what this stuff is before I finished the books. And, thank goodness, they didn't."

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". BridgeToTheStars.net. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- ↑ Robert Butler (3 December 2007). "An Interview with Philip Pullman". The Economist. Intelligent Life. Archived from the original on 5 March 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- ↑ "Pullman's Jungian concept of the soul": Lenz (2005: 163)

- ↑ Parry, Idris. "Online Traduction". Southern Cross Review. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ Fried, Kerry. "Darkness Visible: An Interview with Philip Pullman". Amazon.com. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ↑ Ezard, John (3 June 2002). "Narnia books attacked as racist and sexist". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ↑ Abley, Mark (4 December 2007). "Writing the book on intolerance". The Star. Toronto. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ↑ Crosby, Vanessa. "Innocence and Experience: The Subversion of the Child Hero Archetype in Philip Pullman's Speculative Soteriology" (PDF). University of Sydney. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ↑ Miller, Laura (26 December 2005). "Far From Narnia: Philip Pullman's secular fantasy for children". The New Yorker. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ↑ "Living Archive: Celebrating the Carnegie and Greenaway Winners". CarnegieGreenaway.org.uk. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ↑ Pauli, Michelle (21 June 2007). "Pullman wins 'Carnegie of Carnegies'". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ↑ "70 years celebration the publics favourite winners of all time". Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ↑ "Children's novel triumphs in 2001 Whitbread Book Of The Year" (Press release). 23 January 2002. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ↑ "Minister congratulates Philip Pullman on Swedish honour". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ↑ "SLA – Philip Pullman receives the Astrid Lindgren Award". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- ↑ "The best novels ever (version 1.2)". The Guardian. London. 19 August 2008. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ↑ "100 Best Young-Adult Books". Time. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ↑

"100 'most inspiring' novels revealed by BBC Arts". BBC News. 5 November 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

The reveal kickstarts the BBC's year-long celebration of literature.

- ↑ Overstreet, Jeffrey (20 February 2006). "Reviews:His Dark Materials". Christianity Today. Archived from the original on 18 March 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ↑ Thomas, John (2006). "Opinion". Librarians' Christian Fellowship. Archived from the original on 6 August 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ↑ BBC News 29 November 2007

- ↑ Grenier, Cynthia (October 2001). "Philip Pullman's Dark Materials". The Morley Institute Inc. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ↑ Donohue, Bill (9 October 2007). ""The Golden Compass" Sparks Protest". The Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights. Archived from the original on 4 January 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- ↑ Byers, David (27 November 2007). "Philip Pullman: Catholic boycotters are 'nitwits'". The Times. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- ↑ "A dark agenda?". Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- ↑ Catholic Herald - The stuff of nightmares - Leonie Caldecott (29 October 1999) |

- ↑ Meacham, Steve (13 December 2003). "The shed where God died". Sydney Morning Herald Online. Retrieved 13 December 2003.

- ↑ Schweizer, Bernard (2005). ""And he's a-going to destroy him": religious subversion in Pullman's His Dark Materials". In Lenz, Millicent; Scott, Carole (eds.). His Dark Materials Illuminated: Critical Essays on Philip Pullman's Trilogy. Wayne State University Press. pp. 160–173. ISBN 0814332072.

- ↑ Petre, Jonathan (10 March 2004). "Williams backs Pullman". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ↑ Rowan, Williams (10 March 2004). "Archbishop wants Pullman in class". BBC News Online. Retrieved 10 March 2004.

- ↑ Oborne, Peter (17 March 2004). "The Dark Materials debate: life, God, the universe...". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- ↑ "Once upon a time... in Oxford". Cittàgazze. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ↑ Flood, Alison (17 December 2014). "Baddies in books: Mrs Coulter, the mother of all evil". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ Bayley, Sian (24 March 2022). "Penguin to publish Pullman's The Collectors in print for the first time". The Bookseller. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ↑ Saner, Emine (17 February 2017). "The Book of Dust: after 17 years, Pullman's latest work has new relevance". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ↑ "Philip Pullman announces new book The Secret Commonwealth". Penguin Books. 26 February 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ↑ His Dark Materials: Serpentine

- ↑ The Bookseller

- ↑ "Philip Pullman: His Dark Materials author announces new trilogy The Book of Dust". The Independent. 15 February 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ↑ Eames, Tom; Jeffery, Morgan (27 July 2018). "His Dark Materials TV series: All you need to know". Digital Spy. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ↑ Dawtrey, Adam (13 March 2008). "'Compass' spins foreign frenzy". Penske Media Corporation. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ "'Golden Compass' Director Chris Weitz Answers Your Questions: Part I by Brian Jacks". MTV Movies Blog. Archived from the original on 15 November 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ↑ Heritage, Stuart (15 December 2009). "Who killed off The Golden Compass?". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ↑ "BBC One commissions adaptation of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials". 3 November 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ↑ "Jack Thorne opens up about His Dark Materials TV Series".

- 1 2 "His Dark Materials: Behind the scenes of the TV adaptation". BBC. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ↑ "'His Dark Materials' Release Date". AV Club. 12 September 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ↑ McCreesh, Louise (24 October 2020). "His Dark Materials season 2 will launch in the US on November 16". Digital Spy. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "His Dark Materials TV series on the BBC: Casting, characters, start date - everything you need to know". Digital Spy. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

Further reading

Books

- Frost, Laurie; et al. (2006). The Elements of His Dark Materials: A Guide to Philip Pullman's trilogy. Buffalo Grove, IL: Fell Press. ISBN 0-9759430-1-4. OCLC 73312820.

- Gribbin, John and Mary (2005). The Science of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials. Knopf Books for Young Readers. ISBN 0-375-83144-4.

- Lenz, Millicent and Carole Scott (2005). His Dark Materials Illuminated: Critical Essays on Phillip Pullman's Trilogy. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3207-2.

- Raymond-Pickard, Hugh (2004). The Devil's Account: Philip Pullman and Christianity. London: Darton, Longman & Todd. ISBN 978-0-232-52563-2.

- Squires, Claire (2003). Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials Trilogy: A Reader's Guide. New York, N.Y.: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-1479-6.

- Squires, Claire (2006). Philip Pullman, Master Storyteller: A Guide to the Worlds of His Dark Materials. New York, N.Y.: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1716-9. OCLC 70158423.

- Tucker, Nicholas (2003). Darkness Visible: Inside the World of Philip Pullman. Cambridge: Wizard Books. ISBN 978-1-84046-482-5. OCLC 52876221.

- Wheat, Leonard F. (2008). Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials: A Multiple Allegory: Attacking Religious Superstition in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and Paradise Lost. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-59102-589-4. OCLC 152580912.

- Yeffeth, Glenn (2005). Navigating the Golden Compass: Religion, Science and Daemonology in His Dark Materials. Dallas: Benbella Books. ISBN 1-932100-52-0.

Articles

- "His Dark Materials". BBC Radio 4. Arts and Drama. BBC. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019.

- Horobin, Simon (21 November 2019). "The mysterious world of His Dark Materials: how to decode the story's linguistic secrets". The Conversation.

- Pullman, Philip. "The Republic of Heaven".

The Horn Book Magazine,1 November 2001 (from a lecture given in 2000).