The Labour Party has been part of the political scene in Ireland throughout the state's existence. Although never attracting majority support, it has repeatedly participated in coalition governments. The party was established in 1912 by James Connolly, James Larkin, and William O'Brien and others as the political wing of the Irish Trades Union Congress.[1] It intended to participate in a Dublin Parliament that would follow passage of the Home Rule Act 1914, which was suspended on the outbreak of World War I. Connolly was executed following the Easter Rising in 1916, and was succeeded as leader by Thomas Johnson. The party stood aside from the elections of 1918 and 1921,[2] but despite divisions over acceptance of the Anglo-Irish Treaty it took approximately 20% of the vote in the 1922 elections,[3] initially forming the main opposition party in the Dáil Éireann (parliament) of the Irish Free State. Farm labourers already influenced by D.D. Sheehan's Irish Land and Labour Association (ILLA) factions were absorbed into urban-based unions, which contributed significantly to the expansion of the Irish trade union movement after the First World War. For much of the 20th century, the Irish Labour Party derived the majority of its Dáil strength from TDs who were relatively un-ideological and independent-minded, and were supported by agricultural labourers.[4] It was originally organised, and contested elections as, the Irish Labour Party and Trades Union Congress, until a formal separation between the ITUC and the political party occurred in March 1930.[5]

The subsequent years were marked by rivalry between factions led by William O'Brien and James Larkin, with William Norton becoming leader. Between 1932 and 1938 the Labour Party supported Éamon de Valera's minority Fianna Fáil government. From 1948 to 1951 and from 1954 to 1957 the Labour Party entered government alongside Fine Gael and other parties, with Norton as Tánaiste. During this period the party also stood for elections in Northern Ireland, after a split in the Northern Ireland Labour Party. In 1960 Brendan Corish became the new Labour leader. As leader he advocated and introduced more socialist policies to the party. Between 1973 and 1987 Labour three times more went into coalition governments with Fine Gael. Dick Spring became leader in 1982, amid growing controversy within the party over these coalitions and the growth of parties to the left of Labour.

In 1990 Mary Robinson became President of Ireland with Labour support.[2] After mergers with the Democratic Socialist Party and the Independent Socialist Party, Labour performed well in the 1992 general election and formed a coalition with Fianna Fáil, with Spring as Tánaiste. then in 1994 without a further election joined a coalition with Fine Gael and Democratic Left (the "Rainbow Coalition").[2] After defeat in the 1997 general election, Labour merged with Democratic Left, and the former Democratic Left member Pat Rabbitte became leader in 2002. Rabbitte implemented the "Mullingar Accord", a pre-election voting pact with Fine Gael, but this did not lead to greater election success for Labour in the 2007 elections, and Rabbitte resigned to be replaced by Eamon Gilmore. The 2011 general election saw one of Labour's best results, with over 19% of the first-preference votes. Labour once more entered a coalition government with Fine Gael, and the Irish presidential election later that year saw the Labour Party's candidate, Michael D. Higgins, elected as president. However, Labour in government experienced a series of dismissals and resignations among its members in the Dáil. In 2014, Gilmore resigned as party leader after Labour's poor performance in the European and local elections, and Joan Burton was elected as the new leader.

The Labour Party is regarded a party of the centre-left[6] which has been described as a social democratic party[7] but is referred to in its constitution as a democratic socialist party.[8] Its constitution refers to the party as a "movement of democratic socialists, social democrats, environmentalists, progressives, feminists (and) trade unionists".[8] It has been described as a "big tent" party by the Irish Independent.[9] The stance of the Labour Party has changed dramatically over time. The Encyclopaedia Brittanica described Labour in the past as "a cautious, conservative, and surprisingly rural party considering its origins in the trade union movement."[5] In 1964, American historian Emmet Larkin described the Irish Labour Party as "the most opportunistically conservative Labour Party anywhere in the known world", due to its Catholic outlook in an Ireland where 95 percent of the population was Roman Catholic. It was known for its longstanding unwillingness (along with Ireland's other major parties) to support any policy that could be construed as sympathetic to secularism or communism. However, from the 1980s it was associated with advocacy for socially liberal policies, with former leader Eamon Gilmore stating in 2007 that "more than any other political movement, it was Labour and its allies which drove the modernisation of the Irish state".[10]

In the past Labour has been referred to, derisively, as "the political wing of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul.”[11] That Labour was influenced by Catholicism is not unusual in the Irish context (likewise, both Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil were also products of a predominantly Catholic society). Labour's ethos and often its language was profoundly Christian. Following the official separation of the Irish Labour Party and Irish Trade Union Congress into two different organisations in 1930, early drafts of Labour's constitution referred to the responsibilities of the 'Christian state', but these had all been removed by the time the constitution was put before the new party's conference for approval. However, the Free State's commitment to a full-scale devotional revival of Catholicism was reflected in the outlook and policies of the party.[11] The ‘Starry Plough,’ the traditional symbol of Labour, reflects a Catholic tradition and biblical reference to Isaiah 2:3–4, which is integral to its design.[12] Like Fianna Fáil, Labour embraced corporatist policies, again influenced by the Catholic Church. This was deemed to be important for both in terms of winning electoral support from the lower and middle classes.[13] However, Labour later became associated with increasing secularism[14][15][16] and championing socially liberal causes in relation to contraception, divorce, LGBT rights and abortion.[17][18][19][20][21][22] Its support base also shifted greatly towards postmaterialists.[23] The Labour Party also changed its position from Euroscepticism in 1972 to pro-Europeanism and ideological integration with European social-democratic parties.[24][25]

Foundation

In the first decade of the twentieth century, considerable debate took place within the Irish Trades Union Congress on whether the organised trade union movement in Ireland should take part in political activity. James Connolly, and James Larkin as the leaders of the new and dynamic Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU), led the calls for political action and representation for trade unionists. Opposition came from northern trade unionists and others who wanted links with the British Labour Party, and from supporters of the Irish Parliamentary Party. The majority of the ITUC favoured the creation of an Irish labour movement, which was separate from that in Great Britain. The Dublin Trades Council had already constituted a Dublin Labour Party (DLP), and had members elected to Dublin Corporation, including Richard O'Carroll (who died in the Easter Rising in 1916) and Larkin.[26]

The catalyst for the launch of a congress-sponsored party was the introduction and successful progress of the Third Home Rule Bill in 1912.[27] At its meeting in Clonmel, Co. Tipperary, in 1912, the congress took up the question of a political party. James Connolly presented the resolution that the congress establish its own party. He argued that since Home Rule was imminent and would take place once the House of Lords' delaying powers were exhausted in two years' time, that this period should be used to organise the new party. Connolly's resolution was carried by a wide margin with 49 voting for; 19 against; and 19 abstaining.[28]

.jpg.webp)

In August 1912, William Partridge, a nationalist city councillor on Dublin Corporation, was dismissed from employment by the Great Southern & Western Railway for protesting against preferential promotion of Protestants over Catholics in the Inchicore works. He became a full time paid-official for the IT&GWU, and organised in Co. Dublin and Cork City. Partridge, a prolific contributor to the IT&GWU organ, the Irish Worker, was known for combining his fervent Catholic beliefs with radical syndicalist convictions. He won a seat for the newly launched Labour Party in the January 1913 municipal elections in Dublin.[29]

The new congress also supported the introduction of salaries for members of parliament, public funding of elections and female suffrage. The founding of the Labour Party was disrupted by personality differences between Larkin and his fellow leaders, including Connolly (Connolly also distrusted Larkin).[30] Nevertheless, the 1913 congress meeting under William O'Brien's chairmanship instructed the executive to proceed with the writing of a party constitution. The ITUC took no part in the 1913 lock-out struggle in Dublin, and labour candidates did poorly in local elections in Dublin in January 1914.

During this period, George William Russell (also known as 'AE') and Connolly engaged in a public written discussion, where they read and responded to each other's concepts on social and political structure. This dialogue took place by means of the Irish Homestead newspaper, and Connolly's works on labour in Ireland. Each individual presented the other with an otherwise difficult-to-reach audience: urban workers for Russell, and agricultural labourers and smallholders for Connolly. Russell regarded Connolly as a "really intellectual leader."[31]

Irishmen! Join the Citizen Army NOW and help us to build an Irish Co-operative Commonwealth

https://bid.whytes.ie/lots/view/1-5V6YRV/1916-recruiting-poster-for-the-irish-citizen-army

The proposed constitution limited party membership to affiliated trade unions and councils only and excluded individual membership and other involvement, such as by co-operative societies and other socialist groups. Thomas Johnson argued that Labour would be "swamped" by farmer co-operatives and that individuals might join through trade councils. Connolly argued that there should be just one body and that a separate Labour Party as in Britain would encourage the "professional politician". At the 1914 Congress, it was agreed for the first time to seek the reconstruction of society: "the Congress urges that labour unrest can only be ended by the abolition of the capitalist system of wealth production with its inherent injustice and poverty." The same congress changed the name to add "and Labour Party" to its name and became the Irish Trades Union Congress and Labour Party (ITUC[&]LP),[28] changed in 1918 to "Irish Labour Party and Trades Union Congress" (ILP[&]TUC).[32] In party-political contexts it was usually the "Irish Labour Party", or simply "Labour". Upon Larkin's relocation to the US in 1914, his sister Delia (first general secretary of the Irish Women's Workers' Union) found that she did not get on well with James Connolly, Larkin's successor as honorary secretary of the IT&GWU.[33]

The party was seriously troubled by the proposals in 1914 to exclude certain Ulster counties from Home Rule as this would undermine the potential of the new party by excluding the substantial industrial areas of northeast Ulster. Fourteen of the 34 urban seats in the Home Rule parliament were to be in Belfast alone. The start of the First World War in the summer of 1914 transformed the political situation in Ireland. The Home Rule Bill became law but its operation was postponed until after the war. The official Labour position did not directly oppose Irish support for the British war effort, but it was critical of the war in general terms. Labour skirted the issue in an attempt to avoid division between unionist and nationalist trade unionists. Larkin opposed the war before he left for the US and Connolly condemned John Redmond's support for Irish nationalists involvement in army recruitment. Gradually, Labour opposition to the spectre of conscription moved the party's position closer to that of the separatists. To avoid making a decision on the war, Labour called off its congress in 1915.

During the period of the First World War, there existed distinct views and strategies between the organised, unskilled urban labour force in Ireland and the craft-based, co-operative heritage. Nonetheless, the Labour Party and ITUC, as well as the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), sought to establish a "Co-operative Commonwealth."[34][35]

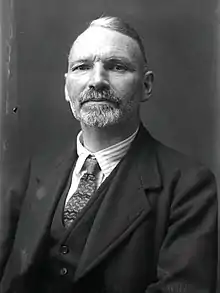

James Connolly was the only leading Labour figure to take part in the Easter Rising in 1916. His execution after the rebellion left the labour movement in some disarray. Liberty Hall, the physical symbol of the labour movement, was destroyed, and the files of the ITUCLP were seized. Many trade union leaders, in Dublin, who had not taken part in the Rising were interned, such as William O'Brien, but they were released later when the British realised that they had no direct involvement. Their absence allowed non-nationalist leaders to come to the fore, especially Thomas Johnson, who was not charismatic, but was a moderate and hardworking man.

Despite his English background, his sheer diligence and devotion to his duties gave him the leading position in labour politics for the next decade. He managed to persuade the authorities to release the trade union leaders in time for the congress meeting in Sligo in August 1916. In his chairman's address, Johnson avoided taking a stand on the Rising and instead called for a minute's silence to honour the memory of Connolly and his comrades. He mourned the dead in the trenches and expressed personal support for the Allies. Johnson's stance in refusing to accept any responsibility for the Rising was regarded as a success as it avoided division between north and south, and laid the stress on economic and social issues.

Early history

In Larkin's absence and Connolly's demise, William O'Brien became the dominant figure in the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union joining it in January 1917, and quickly becoming the leader of that union and wielding considerable influence in the Labour Party. O'Brien, along with Johnson, also dominated the ITUCLP. O'Brien took a leading role in the growing separatist movement that would become the revitalised Sinn Féin. The Labour Party, now led by Thomas Johnson, as successor to such organisations as D.D. Sheehan's (independent labour MPs) Irish Land and Labour Association (ILLA), found itself marginalised by the preeminence that Sinn Féin gave to the national question. De Valera and others expressed sympathy for the labour movement's objectives but made clear that "Labour must wait." The congress-party strongly opposed the moves to introduce conscription into Ireland in 1918, and a twenty-four-hour strike was successfully called on 23 April 1918. Only the Belfast area ignored the strike call. That spring, Labour announced that it would take part in the general election to be held immediately after the war ended. De Valera and other Sinn Féin leaders were highly critical of what they saw as a divisive step by the ITUCLP. At the congress held in August 1918, the executive reported that Labour's hour of destiny had struck and it found the movement ready. O'Brien urged the development of electoral machinery. At this moment, the first signs of the split between O'Brien and the Larkinites became evident. PT Daly, the protégé of Larkin, was locked in a struggle with O'Brien and was beaten by 114 votes to 109 for the post of secretary of the Congress. Daly was later to be purged by O'Brien from the leadership of the ITGWU, setting the scene for a long-lasting split in Irish trade unionism. Following the congress, Labour was finally forced to deal with the issues of national self-determination and abstention from parliament.

Sinn Féin entered into discussions with Labour to secure its abstention from the forthcoming election. Labour was again faced with the dilemma that it might win some seats by entering into a pact with Sinn Féin at the price of alienation of northern unionist workers. Labour offered a radical election programme. Among other objectives, it declared that it would win for the workers the collective ownership and control of the whole produce of their work; adopt the principles of the Russian Revolution; secure the democratic management of all industries in the interest of the nation; and abolish all privileges which were based on property or ancestry.

.jpg.webp)

In the end, a special party conference voted by 96 votes to 23 that the ILPTUC would not contest the 1918 general election, to allow the election to take the form of a plebiscite on Ireland's constitutional status. Sinn Féin won 73 of the 105 seats in the election and convened the First Dáil in January 1919. The Democratic Programme of the First Dáil was jointly drafted by Seán T. O'Kelly of Sinn Féin and Thomas Johnson of Labour. Despite being eventually pruned of much of its socialist content, some of the original radical elements survived. Sinn Féin paid its debt of honour to the Labour Party for its abstention by including in the Programme that every citizen was to be entitled to an adequate share of the produce of the nation's labour; the government would concern itself with the welfare of children, and would care for the aged and infirm; and it would seek "a general and lasting improvement in the conditions under which the working classes live and labour".

However, while Johnson based the initial content of the Democratic Programme on the works of 1916 Rising leader, Pádraig Pearse, its content appeared to be too radical and revolutionary in tone for the Sinn Féin and IRB delegation. Its adoption was only permitted following drastic removals and changes at the insistence of Michael Collins, Harry Boland and Sean T. Ó Ceallaigh. The most significant deletion by Sinn Féin was Labour's original proposal for the "Government to encourage the organisation of people into trade unions and co-operative societies with a view to the control and administration of the industries by the workers engaged in the industries."[36] History Ireland writes that "Labour’s consolation prize of the Democratic Programme was grudgingly conceded, with Michael Collins the biggest begrudger of all."[37]

The Labour Party played a key role in the Anti-Conscription Campaign of 1918. An extensive work stoppage in opposition to compulsory military service took place on 23 April 1918. With the exception of government offices, nearly all businesses shut down outside of Belfast. Catholic workers in particular were warned that they would be unemployed if they participated in the strike. Rallies were organised in 59 districts, including major urban areas like Dublin, Cork, Limerick, and Derry. Priests presided over all except three of the demonstrations, where they issued the anti-conscription vow. A meeting organised by Archbishop Walsh for senior clergy to address strategies for effectively combating the proliferation of "anarchism, republicanism, and Bolshevism" had to be cancelled due to their preoccupation with conducting commemorative Masses in honour of trade unionists.[38]

The cause appears to have gained widespread popularity. Concerning the Bricklayers' union, also known as AGIBSTU, all members of the union unanimously agreed to follow its request to refrain from working on 23 April and to establish a specific fee for the purpose of defence. On Tuesday 23 April, all members of the bricklayers' union in Dublin and throughout the country suspended work as scheduled. A total of three hundred individuals gathered at the union offices located on Cuffe Street in order to formally endorse the anti-conscription vow. The solitary individual who did attend work on that particular day was subjected to a substantial penalty. Although the Bricklayers were a relatively tiny trade union, they were affiliated with larger unions. The largest among them was the ITGWU, which boasted a membership of 40,000, while the Railway union had an additional 20,000 members. Across the nation, nearly all activities came to a sudden stop; transportation, including the companies producing weapons for the conflict, halted their operations for the day. Interestingly, the walkout garnered such widespread backing that some businesses compensated their workers for the day, rendering the collected strike cash unnecessary.[39]

The anti-conscription crusade may be considered as nationalist Ireland's most significant and non-violent triumph over British imperialism in the 20th century. However, Labour's prominent position in the campaign resulted in a hollow triumph, causing internal conflicts within labour organisations and eliciting animosity from their British equivalents. The conscription issue of April 1918 exposed the underlying divisions within the ILP&TUC and its relationship with the British labour movement, as well as the conflicts between the Irish Nationalist Party and the British government. Arthur Henderson, the leader of the British Labour Party and a member of the War Cabinet, frequently received grievances from the ILP&TUC on the special treatment bestowed upon the Irish Nationalist Party. At grassroots levels, British trade unionists frequently harboured resentment towards what they perceived as the Irish evading their proportionate share of the war responsibilities. Mr. A. Beech, the secretary of the Leather Workers Union in Walsall, expressed grievances upon receiving a letter from ILP&TUC president Bill O'Brien, in which he requested assistance for the anti-conscription campaign in Ireland. Jim Connell, the creator of the 'Red Flag,' informed O'Brien that even the controversial Independent Labour Party supporters in London were responding unfavourably to the anti-conscription movement. The harm inflicted upon the internal relations of ILP&TUC was of a lasting kind. Paradoxically, the initial protest against compulsory military service was orchestrated in Belfast by Thomas Johnson and David Campbell, who served as representatives of the city on the executive committee of the Irish Labour Party and Trades Union Congress. The incident occurred at the Custom House on 14 April, prior to the enactment of the Military Service Bill. However, when they attempted to replicate the event three days later at City Hall, loyalist shipyard employees disrupted the debate and Johnson was terminated by his company for "disloyalty".[38][40]

The commencement of the War of Independence in January 1919 redirected the focus of the working class towards the national conflict in an unprecedented manner. Amidst the escalating conflict in Ireland, the British government issued the Motor Permits Order, a regulation stating that starting from 29 November 1919, motor vehicles could only be driven if they had a permit. The purpose of the directive was to facilitate the surveillance of private transportation, which was being used to smuggle weapons. Motor drivers were deeply angered and promptly initiated a strike. The trades council provided unambiguous backing to them. By early 1920, the strike started to weaken and on 8 February 1920, it was terminated. The defiance of the Labour Party against the directive strengthened its dedication to national sovereignty.[41]

University College Cork notes the strong republican rhetoric of the Labour Party during this period. In late 1918, Éamonn O'Mahony, an Irish republican, became president of the Cork Trades Council. The process of Labour in Cork becoming more aligned with republican ideals reached its peak during the municipal elections on 15 January 1920. The British Government had introduced proportional representation in order to undermine the influence of the Republicans, however, they ran with Labour on a joint-ticket in the city council election. The IT&GWU had requested that the nominees of the trades council make a commitment to republicanism, which greatly irritated the Typographical Association. As a result, the Typographical Association declined to financially support the campaigns of these candidates. This coalition won 30 seats out of a possible 49 on Cork Corporation, consequently giving it a four-seat majority. During a special assembly of the Cork Trades Council held on 21 March 1920, the Royal Irish Constabulary was denounced for the murder of Lord Mayor, Tomás Mac Curtain. A general strike was dutifully conducted. The trades council had taken autonomous action in a particular field without being requested by the Irish Trades Union Congress. Despite having previously shown sympathy for nationalist political concerns, Cork Labour's participation in this event marked their initial autonomous demonstration of forthright camaraderie with the republicans.[41]

In a 1919 article in The Watchword of Labour, Fr. Peter Finlay, S.J, was criticised for his condemnation of Labour policy, with the writer describing the similarities between Catholic social teaching and the Labour Party policy, stating that the system proposed by Labour was "perfectly permissible in light of the papal encyclicals." Promoting distributist views, it appealed to the Catholic Archbishop of Dublin to prevent further attacks by clergymen on the party.[42]

Labour took part in the 1920 local elections and won a significant role in local government for the first time. It gained 394 seats compared to 550 for Sinn Féin, 355 for the unionists, 238 for the old nationalists, and 161 independents.

Nonetheless, Padraig Yeates notes that, when Sinn Féin took control of councils and city corporations, and declared their allegiance to Dáil following the 1920 elections, they dismantled the majority of the Poor Law system, including workhouses and hospitals, while also discharging inmates, refusing admissions, and reducing staffing levels, food and pay. These new administrations recommended that the "work shy" should emigrate, and "fallen women" were given to religious orders. Despite this, the subsequent cuts were greeted by ratepayers as an extra victory along the path to independence.[36]

Throughout Ireland, the most notable labour strikes all exhibited prominent republican elements. The fact that the largest demonstration during the time of Irish Labour's political transition was a political action is a clear indication. This protest was the general strike organised by the ITUC on April 13, 1920, with the objective of securing the immediate release of republican hunger-strikers held at Mountjoy Prison and Wormwood Scrubs. The walkout, spanning a duration of two days, achieved spectacular success. While not as extensive as the April 1920 strike, the most significant labour effort of the era was another political action: the blockade imposed by Irish railwaymen and dockers on the transit of military forces and supplies. On a national scale, the embargo persisted until 21 December 1920, and severely hindered the British government's efforts to combat the IRA rebellion. Labour had no hesitation in serving as a supporting entity for the republican cause. The rise of republicanism among workers resulted in the interconnection of ideas such as class awareness, labour union activism, political autonomy, and opposition to imperialism. Labour perceived its struggle as primarily a political issue, rather than one centred on industrial relations.[41]

At the beginning of December 1920, approximately one week preceding the burning of Cork City, a British Labour Party delegation, including their party leader, Arthur Henderson, had arrived in Cork City, accompanied by Tom Johnson. Later, on 14 December, only days following the burning, Johnson returned to Cork City with another two British Labour MPs, John Lawson and William Lunn, and they traversed the city centre's ruins. Johnson donated £200 of Irish Labour Party finances to support, amongst other initiatives, the publication of a pamphlet by Alfred O’Rahilly, titled Who Burnt Cork City?. More than 2,000 copies of O’Rahilly’s pamphlet were sold by March 1921. Seán T. Ó Ceallaigh, the Dáil Éireann representative in Paris, conceded to the Labour Party and Irish Trades Union Congress for their publishing effort.[43]

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 effected the partition of Ireland with elections in June 1921 planned for the lower houses of the parliaments of Northern Ireland and of Southern Ireland. The Labour national executive decided to leave the field to Sinn Féin, although its 1921 report suggested that it was unaware that Sinn Féin intended to use the elections to replace the First Dáil with a Second Dáil.[44] The executive reprimanded Richard Corish and the Wexford Trades Council for accepting his Sinn Féin election nomination. When the truce of July 1921 ended the Irish War of Independence, Labour was not involved in any way in the negotiations that led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921, by which a new Irish Free State would be established as a Dominion of the British Empire equivalent in status to Canada.

Labour in the Irish Free State

The Anglo-Irish Treaty & main opposition party, 1922–1927

The Anglo-Irish Treaty divided the Labour party. It did not take an official stand. From his American prison cell, Jim Larkin opposed the Treaty while the only Labour member of the Dáil, Richard Corish of Wexford spoke and voted for the Treaty. Johnson, never a republican, privately supported the Treaty, while O'Brien did not oppose it. Following the approval of the Treaty by the Dáil in January 1922, the executive of the ILPTUC succeeded at a special conference held in February, in passing a motion to participate in the forthcoming general election. Successful Labour candidates were required to take their seats in the new Free State Dáil, and a reformist programme was adopted.

Johnson and the other Labour leaders tried to stop the slide to civil war to no avail,[45] including holding a one-day national strike across the 26 counties on 24 April. Labour candidates were nominated for the election on 16 June, despite the difficulties of poor organisation, internal opposition to participation and limited finance. When The Collins/De Valera Pact was agreed on 20 May, the pressure on the party was intensified. The Pact provided for the pro and anti Treaty sides to have one agreed slate of candidates with a coalition government to be established afterwards. Other parties and groups, including Labour, were asked to stand down again in the national interest. Effectively, the old Sinn Féin was about to deny a democratic election from being held and to prevent the public expressing their preferences. While de Valera had a notable success in persuading Patrick Hogan, a future Labour Ceann Comhairle, from standing in Clare, 18 other Labour candidates resisted the pressures on them from the IRA and went forward for election. These were perceived as pro-Treaty, and when Michael Collins repudiated the Pact four days before the election, it benefited the Labour Party as well as the pro-Treaty party. Seventeen of the eighteen Labour candidates won seats, with the 18th losing only by 13 votes. Some candidates had nearly twice the quota but had no running mates to transfer their surplus votes.

As well as being a triumph for the Labour Party, the election confirmed the popular acceptance of the Treaty. The Civil War broke out shortly later, between the IRA and the new National Army, and ravaged the country in the following months. The new Dáil did not meet until September preventing Labour from having any influence over events. Public opinion and voting habits crystallised in a deeply polarised fashion in this period between the two sides of the national movement, and led to the effective marginalisation of the Labour Party and of social and economic issues that was to last for the rest of the twentieth century. When the third Dáil eventually met in September, Labour attempted to amend the new Free State Constitution to remove the elements imposed by the Treaty but pragmatically accepted the new order when it was adopted. The Labour deputies took the controversial oath of fidelity to the British monarch, viewing it as a formality.

Labour and Johnson were mocked as naive "do-gooders." Johnson was held in contempt by both sides of the war. His most significant intervention during the Civil War related to events in Kerry in 1923, when contested the government's assurances that the killing of prisoners in Ballyseedy had been accidental. Labour contended that the political and the martial had become too closely connected. Labour strongly opposed the 1922 Public Safety Bill, which permitted death sentences for a range of offences. The first executions under the Act occurred in mid-November provoking a hostile response from Labour Deputies in Dáil. The Voice of Labour, which was heavily censored by the Free State, was highly critical of Black and Tan tactics being used by Provisional Government troops against workers who played no role in the conflict.[46]

Labour had threatened to resign its Dáil seats, but effectively served as the official opposition following the outbreak of the civil war.[47]

.jpg.webp)

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, an economic slump and collapse in union membership led to a loss in support for the party. In the 1923 election Labour only won 14 seats, seeing its share of the vote halved. However, from 1922 until Fianna Fáil TDs took their seats in 1927, Labour was the major opposition party in the Dáil. It attacked the lack of social reform by the Cumann na nGaedheal government. Johnson became the leading figure in the Parliamentary Labour Party and the leader of the Opposition to the new Government. From 1927, a large number of the Labour Party's voters were pre-empted by Fianna Fáil, with its almost identical policies. Labour lacked Fianna Fáil's 'republican' image, which was a contributing factor to this loss.[48] The Irish Labour Party and the Irish Trades Union Congress separated in 1930.[49][50]

Larkin returned to Ireland in April 1923, attacking Labour and the ITUC in his rhetoric.[51] He hoped to resume the leadership role in the ITGWU which he had previously left, but O'Brien resisted him. Larkin also created a pro-communist party called the Irish Worker League. O'Brien regarded Larkin as a "loose cannon." Following a failed challenge to O'Brien's leadership and association with communist militancy, Larkin was expelled from the ITGWU and created the WUI, a communist alternative to the ITGWU, in 1924. Two-thirds of the Dublin membership of the ITGWU defected to the new union. O'Brien blocked the WUI from admission to the ITUC. Larkin was elected to Dáil Éireann at the September 1927 general election. However, the Labour Party prevented him from taking his seat as an undischarged bankrupt for losing a libel case against Labour leader Tom Johnson.[52][53][54][55][56][57][58]

During the period from 1927 to 1933, the political groups of the Irish Free State saw significant and volatile shifts in their fortunes. The decade was characterised by significant transformation for the Labour Party. It was not simply a period of transition for Labour as they adjusted to a government led by de Valera instead of Cosgrave. It was a time of significant change as Labour reassessed its stance on various issues: its association with the two main parties, its role with regard to trade unions, its public perception, its leadership, and even its basic comprehension of politics. Labour expressed strong disapproval of the extreme actions used by both sides during the Civil War, while simultaneously highlighting the importance of socio-economic matters. In the 1920s, Labour persistently criticised the emphasis on constitutional issues that were inherited from the Treaty and Civil War. The Party had an unforeseen advantage in this matter, since Labour became the official Opposition in the Dáil opposite to the CnG administration. Labour's standing underwent a significant transformation with the arrival of Fianna Fáil to the Dáil in August 1927. Labour's status was diminished to that of a minority party, a fact emphasised by the Party's reduction of nine seats in the September 1927 general election.[59]

Party representatives in the 1920s expressed dissatisfaction with the insufficient backing from trade union members during electoral campaigns. Trade unions had mostly focused on social and economic matters, suggesting that political concerns should be approached differently, despite the presence of Labour as the 'Congress Party'. There was, then, an abnormality in a political party that primarily, if not exclusively, received support from entities whose objectives were categorised as social and economic, rather than political. An instance illustrating this was the demeanour shown by the Irish National Teachers' Organisation (INTO). Following the September 1927 election, the INTO, a prominent union within the party, corresponded with the Labour Party, stating that "it should be considered but reasonable on the part of the teachers to request the Labour Party to adopt an attitude of strict neutrality on the 'purely political' questions (as many members will not agree with the Party's stance) and to devote all their attention to social and economic problems." Ironically, it was INTO General Secretary, Thomas J. O'Connell, to become Johnson's successor as party leader, who wrote the letter, without explaining how a political party could be politically neutral.[59]

In a 1930 article of The Watchword, the Rev. Malcolm MacColl, a British Catholic priest, praised the Irish labour movement and criticised the attitudes of the "traditional [Protestant] Ascendancy" towards Irish Catholics and the Catholic Church, promoting the Catholic Action movement for the up-liftment of working-class Catholics in Ireland.[60] In the same year, an article condemned the use of "girl and juvenile labour" in Co. Cork by employers "who call themselves Christians, and, in fact, Catholics."[61]

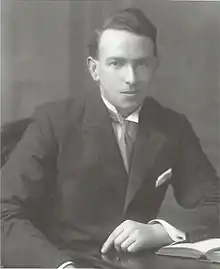

William Norton becomes leader, 1932

William 'Bill' Norton, youngest of the seven sitting Labour TDs, was chosen as party leader on 26 February 1932, succeeding Thomas J. O'Connell, who had lost his seat.[50] In 1932, the Labour Party supported Éamon de Valera's first Fianna Fáil government, which had proposed a programme of social reform with which the party was in sympathy.[62] As the Fianna Fáil developed and distanced itself from being seen as just an isolated component of the larger republican movement, socio-economic issues became more significant inside the party. The resolutions passed at the 1929 Ard Fheis started with addressing the issue of unemployment and concluded with a call for the provision of homes for workers. A contemporaneous conservative commentator noted that there was a growing focus on the advancement of domestic industry, making it a greater challenge to distinguish between the policies of Fianna Fáil and Labour. Despite often aligning with Fianna Fáil to oppose the Cosgrave led government at the time, Labour Party representatives saw FF and CnG as essentially equivalent. Undoubtedly, the resemblance of the two parties was so evident that anger within Labour regarding the widespread backing that they received could be observed.[59]

Assuming leadership of a party which had had its representation heavily reduced, Norton provided energetic leadership, defining a clearer party identity which placed greater emphasis on Catholicism, Irish republicanism, and, was initially more socialistic. However, the party retreated from the latter not long later.[50] Quoting economists such as John Maynard Keynes, the party lobbied for financial reform. It condemned debt-based credit, usury and private control of the money system. In an article on private banking in The Watchword, for example, it declared that "this fictitious gold basis; private-bank made money system, promotes a debt building process that robs the producer and wage-earner, and finally breaks down on its own weight."[63][64]

The issues around image and organisation that plagued the Labour Party diminished following 1932. After Norton assumed the role of Party Leader, any such instances of humiliating divisions were expressly outlawed. The Party's crucial stance in 1932 emphasised the need for stringent discipline, which was also reflected in the attitude of the freshly appointed leader. Superficially, Norton seemed to be an unlikely candidate to succeed O'Connell. Norton only had a brief stint of Dail experience during the term of 1926-27. He suffered a resounding loss in a by-election in 1931. William Davin, James Everett, and Richard Corish were more probable candidates for succession, due to their extensive legislative experience. Davin was perhaps the most exceptional prospect due to his consistent and very effective speaking skills. One advantage Norton had was that he held the position of General Secretary of the Post Office Workers' Union, which was one of the main unions associated with the Labour Party. Nevertheless, Norton was not only a trade unionist. In fact, he initiated the proposal to detach the Party from the ITUC. By advocating for the creation of a "real-life Labour Party," he displayed a directness that set him apart from most Party representatives, and definitely from past Party Leaders. Norton not only exhibited an aesthetic that differed from his predecessors, but he also embodied a new age. Johnson was born in 1872, O'Connell in 1882, and Norton in 1900, with the latter coming of age at the peak of the War of Independence. He was indeed a member of the revolutionary generation responsible for pursuing Irish independence. His history is obviously apparent in his endorsement of de Valera's stance on matters involving the elimination of the Oath of Allegiance, and particularly on the matter of land annuities. Norton's republican affiliation was underscored by his strong personal rapport with Valera, which he often highlighted in his public discourses.[59]

In the 1930s, the Labour Party received adverse publicity and was accused of tacitly supporting Soviet Communism, and the Irish Trades Union Congress was accused of circulating an article which proclaimed the Roman Catholic Church as an enemy of the workers. These were extremely negative accusations in an Ireland that was ardently anti-communist. William Norton wrote a letter to Pope Pius XII (then known as Cardinal Pacelli, Secretary of State at the Vatican), stating that "as a Catholic and the accepted leader of the Irish Labour Party, I desire most empathetically to repudiate both statements". A pamphlet was produced, entitled Cemeteries of Liberty, which asserted that the Labour Party viewed both Communism and Fascism as "Cemeteries of Liberty". In an article, the Rev. Dr. George Clune, at the suggestion of the Rev. Fr. Edward Cahill, stated in support of the Labour Party that "the Irish Labour Party never at any time construed the term 'A Workers' Republic' as meaning a Republic of the Russian sort. This phrase was evolved by Connolly more than forty years ago, long before the establishment of Russian Bolshevism. This term was used by him, and subsequently accepted by the Irish Labour Party to denote a republic within which working men would have family security as contra-distinguished from the Republics of France and America, which suffered from the excesses of Capitalism... The Party does not stand for (nor did it ever stand) for the nationalisation of private property, but for the nationalisation of certain services such as transport and flour-milling. Hence, this comes within the pronouncements of Pope Pius XI".[65]

“The Labour Party aims at the establishment of a Democratic Republic for all Ireland. Not a replica of those republics which compete with monarchies in the exploitation of the workers, in which wealth, power and privilege are in the hands of a self-seeking few while misery, poverty and economic servitude are the lot of the mass of the people. A republic which perpetuates the exploitation of the many for the advantage of the few would merely be a change in nomenclature; the economic and social ills of the people would still be unsolved and the paradox would continue of a social system in which well-endowed financial institutions exist side-by-side with the poorhouse, and the mansion towers over the slums and mud-cabins as a reminder of the power of wealth over the people.”

Labour News (19/6/1937)

At a mass meeting held in Limerick city in 1936, Michael J. Keyes, a Labour TD, president of the ITUC and Mayor of Limerick, hailed the work of the pro-Franco Irish Christian Front organisation in its efforts “to bring into existence in this country a social and economic system based on the Christian ideals of life as expressed in the papal encyclicals and thereby to overcome the evils of socialism which are altogether contrary to Christian principles.”[66] Labour also promoted the creation of a 'Christian State.'[67]

Ahead of the 1937 general election, Labour News, the party's main publication, ran a feature spread of its programme, featuring the slogan Put Real Human Interest Before the Exactions of Financiers![68] The party representatives also described themselves in this period as "Catholics first and politicians afterwards."[69] In that same year, the party praised the Catholic Action movement.[70] William Norton would attack what he called 'Godless Communism.'[69]

In September 1938, Maud Gonne MacBride endorsed Labour's Social Outlook, a party policy platform written and presented by former Cork TD, Timothy Quill.[71] It described Labour's financial policy, by which banking and credit would be made a State function, so that "the credit of the country would be used to benefit all the people."[72]

At the 1936 party conference, Wexford Labour politician Richard Corish said of himself; "I am neither a socialist, syndicalist or communist. I am a Catholic, thank God, and am prepared to take my teaching from the Church".[73] In August 1939, Cork politician Richard Anthony told the forty-fifth ITUC that he would prefer "fascism to a dictatorship of the proletariat".[74] In February 1939, Cork TD, James Hickey, then serving as Lord Mayor of Cork, snubbed the crew of the Nazi warship, the Schleisen, (then docked at Cork Harbour) on the basis that Adolf Hitler had insulted the Pope. The incident grabbed international headlines. Relations between the Vatican and Nazi Germany were toxic at the time.[75]

During the 1930s, the party's publications criticised the Irish Catholic newspaper for harbouring right-wing views, claiming that they had contradicted the teaching of the Catholic encyclicals. In one such article, Labour News accused the publication of spreading "anti-Labour falsehoods" and of "cashing in on Christianity."[76][77][78]

Split with National Labour, establishment in Northern Ireland, and the first coalition governments

In the 1942 local elections, Co. Kildare (home of party leader, Bill Norton) became the first county in which the Labour party won an over all majority.[79] Labour also won a then-record of five seats on Cork Corporation that year.[80] Encouraged by a strong performance nationally in the August 1942 local elections, Labour campaigned in the June 1943 general election on the slogan ‘Labour to power.' It won seventeen seats on 16% of the vote, its best showing in sixteen years. The party elected its first TD in Co. Kerry, Dan Spring, for the Kerry North constituency. However, the re-emergence of James Larkin in the Labour Party would present Norton with his gravest crisis to date.[50][81]

Despite efforts in the 1930s to sternly downplay the idea of Communist influence over the party, by the 1940s internal conflict and complementary allegations of communist infiltration caused a split in the Labour Party and the Irish Congress of Trade Unions. Tensions peaked in 1941 when party founder Jim Larkin and a number of his supporters were re-admitted to the party and subsequently accused of "taking over" Labour branches in Dublin. In response William X. O'Brien left with six TDs in 1944, founding the National Labour Party (NLP), whose leader was James Everett. O'Brien also withdrew the ITGWU[82] from the Irish Trades Unions Congress and set up his own congress. The split damaged the Labour movement in the 1944 general election. The ITGWU attacked "Larkinite and Communist Party elements" which it claimed had taken over the Labour Party. The split and the anti-communist assault put Labour on the defensive. It launched its own inquiry into communist involvement, which resulted in the expulsion of six members (Spanish Civil War veteran, Michael O'Riordan, future chair of the Communist Party of Ireland, was notably expelled by veteran Cork politicians Timothy Quill and T.J Murphy). Alfred O'Rahilly in The Communist Front and the Attack on Irish Labour widened the assault to include the influence of British-based unions and communists in the ITUC. The National Labour Party juxtaposed itself against this by emphasising its commitment to Catholic Social Teaching. However, Labour also continued to emphasise its anti-communist credentials. Speaking at a National Labour delegate conference in October 1944, Everett stated that the Labour Party's attitude "to the new organisation, 'The Vanguard,' showed how helplessly the party leaders were caught in the Communist web" and "the individuals running the Vanguard were the same people who crashed into the party in 1942, founded the notorious Dublin Central branch and caused the party constitution to be torn up."[83] It was only after Larkin's death in 1947 that an attempt at unity could be made.[84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91] Norton delivered a graveside oration at Larkin's funeral.[92] However, National Labour criticised Labour's renewed calls for unity and that "failure to maintain unity within the Party occurred in 1943 when some members of the Administrative Council of the Party allowed themselves to be frightened or fooled into handing over control to a self-styled Dublin Executive, from whom they took their orders." They also stated that "those who wrecked the Labour Party four years ago, and had previously, by their policy of intrigue sought to make it their mouthpiece for Communist propaganda, cannot be permitted to continue their activities under cover of a democratic political organisation." National Labour also condemned the alleged influence of British trade unions in the Labour Party.[93]

Before his death Larkin, having become disillusioned with both communism and revolutionary trade unionism, was attended by Archbishop John Charles McQuaid and reconciled with the Catholic Church.[94]

During this period the party also occasionally stood for election in Northern Ireland, on occasion winning the odd seat at both the Westminster Parliament and Stormont Parliament in the Belfast area. However the party is not known to have contested an election in the region since Gerry Fitt, then the party's sole Stormont MP, left the party to form the Republican Labour Party in 1964.

From 1948 to 1951 and from 1954 to 1957 the Labour Party was the second-largest partner in the two inter-party governments. William Norton, the Labour leader, became Tánaiste and Minister for Social Welfare on both occasions.[95]

In March 1949, Norton sued the Irish Press (against legal advice) when it accused him of "occupying most of his time with Party matters and (leaving) the Department to run itself." Norton won a pyrrhic victory, with the jury awarding him £1 in damages. This lead Fianna Fáil's Sean MacEntee to dub Norton as "Billy the Quid." This case simply lead credence to the notion that Norton had indeed been neglecting his ministerial duties.[96]

History Ireland gives Norton a favourable assessment, writing that he "achieved much. The old age pension had stood at ten shillings a week for decades. There had been appeals for an extra shilling or two in the 1946 and 1947 budgets, but to no avail. Norton increased the rate by five shillings (50%) in his first year. The sums involved seem ridiculous today, but they represented real money 60 years ago. The tánaiste also proportionately increased pensions for widows, orphans and the blind. Furthermore, the means test (by which entitlements were assessed) was modified."[97]

As minister for local government, West Cork based Labour politician T.J Murphy was preoccupied with a housing drive, transforming 'local government into a virtual department of housing'. He was largely responsible for the huge increase in government expenditure on housing under the first inter-party government, in spite of strong opposition from the Department of Finance. Dublin was the chief target of his housing plans, and he was instrumental in the appointment of the Dublin assistant city and county manager, T. C. O'Mahony as a full-time director of housing. The blueprint for his housing scheme, Ireland is building (1949), set a target of building 100,000 new houses in ten years. Murphy did not live to see the completion of his plans, dying suddenly in 1949.[98]

Dr. David McCullagh has stated that the "Second Inter-Party Government has a reasonable claim to being the worst Government in the history of the State. Which, when you think about the competition, is quite a claim to make." Norton took over the Department of Industry and Commerce. McCullagh is critical of Norton's time in this portfolio, writing that "He claimed, apparently as a good thing, that they had 'given the country quiet'; but what the country needed was a kick up the… well, let’s just say, the country needed a more dynamic approach. Part of the problem was Norton, who had gone native in Industry and Commerce. In June 1954, shortly after returning to the Taoiseach’s office, Costello asked Industry and Commerce to examine changes to the Control of Manufactures Act. Norton replied in September that no changes were required, and warning that allowing uncontrolled access to foreign capital would be 'a grave threat to existing and future industrial development'".[99]

A large amount of animosity and venom was voiced and written against Norton, particularly during the vicious splits in the trade union and labour movement in the 1940s, was regularly featured in the editorials of the Irish Press and among the break-away Congress of Irish Unions (CIU) leadership, who did not forgive him as a key figure in the formation of the first inter-party government. In 1959, Norton held a private audience with Pope John XXIII.[92]

Ideological shift and coalition, 1960–1981

Leadership of Brendan Corish, 1960–1977

Brendan Corish became the new Labour leader in 1960. As leader, he advocated for more socialist policies to be adopted by the party; although initially tempering by this describing these policies as "a form of Christian socialism",[100] he would later feel comfortable enough to drop the "Christian" prefix. In contrast to his predecessors, Corish adopted an anti-coalition stance. Labour promoted a Eurosceptic outlook in the 1961 general election, and in 1972, the party campaigned against membership of the European Economic Community (EEC).[101]

A member of the Knights of St. Columbanus, in 1953 Corish had stated that "I am a Catholic first and an Irishman second."[102][103] However, future leader Michael O'Leary held a strong personal influence over him on pushing for the separation of church and state (O'Leary himself engaged in catholic devotional practices; cynical observers assumed these were adopted for electoral reasons, but in later life, after leaving politics, he was a regular attender at papally-approved Tridentine masses in Dublin).[6] He attempted to give his fractious, divided party a coherent national identity, lurched it to the left and insisted Labour was the natural party of social justice.[104] In the late 1960s, Labour began to embrace the New Left, and Corish presented his A New Republic document at the 1967 Labour national conference, alongside a famous speech which declared that "The seventies will be socialist", which later became a Labour campaign slogan.[105] Corish's new socialist direction for Labour was generally well-received internally; the membership's faith in Corish had already been bolstered by encouraging election results in 1965 and 1967.[106] However, there were a number of notable and vocal dissidents: Patrick Norton, Labour politician and son of former leader William 'Bill' Norton, accused the party of embracing "Cuban socialism" and left Labour in 1967, insisting it had been captured by "a small but vocal group of fellow travellers". He joined Fianna Fáil.[107] Following further accusations of being sympathetic to communism ahead of the 1969 general election, Labour politician Brendan Halligan cited papal encyclicals, such as St. John XXIII's Mater at Magistra, to support Labour's position.[108][109][110][111] At the party conference in January 1969, Cork politician Eileen Desmond stated that “as a Catholic mother,” she found nothing objectionable to Labour's proposals for greater state involvement in the provision of education and healthcare. However, she partly attributed her defeat in the Mid-Cork constituency at the 1969 general election to the party having moved “too far to the left.”[112]

Although Labour's share of the vote improved to 17% in the 1969 Irish general election, the best in 50 years, the party only won 17 seats – 5 fewer than in the 1965 general election. The result dented Corish's confidence and caused him to reconsider his anti-coalition stance.[104]

The seventies will be socialist. At the next general election Labour must . . . make a major breakthrough in seats and votes. It must demonstrate convincingly that it has the capacity to become the Government of this country. Our present position is a mere transition phase on the road to securing the support of the majority of our people. At the next general election (we) must face the electorate with a clear-cut alternative to the conservatism of the past and present; and emerge . . . . as the Party which will shape the seventies. What I offer now is the outline of a new society, a New Republic.[105]

Brendan Corish, The 1967 Labour national conference

Between 1973 and 1977, the Labour Party formed a coalition government with Fine Gael. With the change of government in March 1973, Corish became tánaiste and minister for health and social welfare. His conception of Labour in government can be summed up as the provision of decent social welfare provision. This led him to regard possession of the social welfare and health portfolios as the most important for Labour. While there was of course nothing aberrant in the view that social welfare and health were crucial areas of advance for ordinary people, it prevented larger policy prizes being won in the two-party government lottery of March 1973. It had the strange result that Corish turned down Cosgrave's offer of the Department of Finance, though his innate modesty also played a part in this decision. His greatest achievement within the 1973–7 government was to maintain its unity and in particular to maintain discipline among the ranks of the Labour ministers. It was a time of rising unemployment and inflation against the backdrop of a world oil crisis. The new government had to contend with IRA and Loyalist terrorism, facilitate negotiations leading to the Sunningdale Agreement, and manage Ireland's arrival on the European stage. As minister he introduced reforms in the social welfare system by reducing the qualifying age for old age pensions from 70 to 66 years, and modifying the means test for non-contributory pensions. He provided for a deserted wives benefit and unmarried mother's allowance, as well as new allowances for single women aged over 58 and made improvements under the adoption acts. More generally he supported legislation to amend the law against subversives and legislation which strengthened and extended certain provisions of the Offences Against the State Act.[104]

The liberal activist politician, Dr Noël Browne, was admitted as a Labour Party member on 27 November 1963, and was to remain a member until 1977 – the longest period by far that he was to be a member of any political organisation. His entry into the party occurred following the resignation of his nemesis, William Norton, from the leadership role in 1960. He was regarded as a lodestone for the nascent left-wing enthusiasm in sections of the electorate, and among younger members of Labour in particular. When Labour went into the 1973 election on the basis of a pre-election pact with Fine Gael, Noel Browne refused to sign the party pledge and was accordingly deselected as a party candidate for Dublin South-East. Immediately afterwards, however, he stood as an independent in the Dublin University constituency in the Seanad election, and was successful. For the next four years he spoke, often eloquently, on a range of issues which principally included matters like the role of the Catholic church, contraception, divorce and – on one occasion – therapeutic abortion, none of which endeared him greatly to his fellow party members, with whom he was now in an increasingly distant relationship.[113]

Cluskey succeeds as leader, 1977-1981

Following the defeat of the coalition in the 1977 general election, Corish resigned as leader and was succeeded in the role by Frank Cluskey.[104] O'Leary and Cluskey both stood for the leadership. They had been rivals for some time and the contest mirrored divisions within the party going back to the 1940s. Cluskey was a member of the Workers' Union of Ireland, and was supported by the two other WUI dáil deputies. Six of the eight ITGWU deputies, strongly encouraged by their general secretary, Michael Mullen, supported O'Leary. Most traditionalist, rural TDs favoured O'Leary, despite disagreement with many of his views, while most Dublin TDs backed Cluskey.[6] In October of the same year, Noel Browne and his allies formed a new party – the Socialist Labour Party.[113]

A sharp and effective critic of Charles Haughey, on the latter's election as Taoiseach in 1979, Cluskey gave a blistering Dáil speech, castigating Haughey's close relationship with wealthy and influential individuals who operated in "a grey area of Irish business and commercial life." However, in lacking natural charisma or a studied polish, Cluskey was less successful in dealings with the news media. His dour, 'shop steward's exterior' failed to appeal to television audiences or the broad electorate. Under Cluskey's leadership, Labour adopted a new policy programme in 1980, which re-affirmed the party's socialist aspirations. It advocated for major reforms in healthcare, education, and banking. However, the most radical proposals were diluted in the 1981 election manifesto, which mainly concentrated on proposals to address unemployment. Cluskey hesitated in forming clear positions on such social issues as contraception and divorce. He told lobbyists in favour of constitutional amendment banning abortion that Labour would consider the need for the amendment, but also suggested that a group purporting to be ‘pro-life,’ should in the same way also be advocating for improved facilities for poor and single-parent families.[114]

In the 1981 general election, Labour dropped under 10% of the national vote for the first time in a quarter century. Cluskey lost his seat in this election. His distaste for constituency work, which he regarded as part of the patronage system, as well as the contesting of former Labour TD, John O'Connell, as an independent in the same constituency, were the main contributors to his defeat.[114]

The 1981-1990: coalition, internal feuding, electoral decline and regrowth

O'Leary finally became party leader after Cluskey lost his seat in the 1981 general election. He agreed, reluctantly, to resign his European seat in favour of Cluskey. After achieving several concessions on economic policy in negotiating a programme for government with FitzGerald, he became tánaiste and minister for energy in the short-lived Fine Gael–Labour coalition of 1981–2. He had sought, but failed to obtain, a commitment that the government would hold a referendum on the existing constitutional ban on divorce. O'Leary also declared his personal opposition to the proposed eighth or 'pro-life' amendment to the constitution (about which Cluskey had been non-committal), claiming its wording was legally flawed and represented Catholic sectarianism. This represented the first breach in the apparent party consensus on the abortion issue and moved the Labour party towards opposing a constitutional referendum.[6]

From 1982 to 1987, under the leadership of Dick Spring, Labour participated in coalition governments with Fine Gael. In the later part of the second of these coalition terms, the country's poor economic and fiscal situation required strict curtailing of government spending, and Labour bore much of the blame for unpopular cutbacks in health and other social services. In the 1987 general election it received only 6.4% of the vote, and its vote was increasingly threatened by the growth of the Workers' Party. Fianna Fáil formed a minority government from 1987 to 1989 and then a coalition with the Progressive Democrats.

The 1980s saw fierce disagreements between left and right wings of the party. The more radical elements, led by figures including Emmet Stagg, opposed the idea of going into coalition government with either of the major centre-right parties. At the 1989 Labour conference in Tralee a number of socialist and Marxist activists, organised around the Militant newspaper, were expelled. These expulsions continued during the early 1990s and those expelled, including Joe Higgins went on to found the Socialist Party.

These rows ended with the defeat of the anti-coalition left. In the period since, there have been further discussions about coalitions in the Party but these disagreements have primarily been over the merits of different coalition partners rather than over the principle of coalition. Related arguments have taken place from time to time over the wisdom of entering into pre-election voting pacts with other parties. Indeed, former radicals like Stagg himself and Michael D. Higgins now themselves support coalition.

1990-1999: Mary Robinson and coalitions of different hues

.jpg.webp)

In 1990 Mary Robinson became the first President of Ireland to have been proposed by the Labour Party, although she contested the election as an independent candidate. Not only was it the first time a woman held the office but it was the first time, apart from Douglas Hyde, that a non-Fianna Fáil candidate was elected. Mary Robinson became one of the most outspoken and active presidents in the history of the state. In 1990 the Party merged with the Limerick East TD Jim Kemmy's Democratic Socialist Party and in 1992 it merged with Sligo–Leitrim TD Declan Bree's Independent Socialist Party.

At the 1992 general election on 25 November Labour won a record 19.3% of the first-preference votes, more than twice its share in the 1989 election. The party's representation in the Dáil doubled to 33 seats and, after a period of negotiations, Labour formed a coalition with Fianna Fáil, taking office in January 1993 as the 23rd Government of Ireland.[3] Fianna Fáil leader Albert Reynolds remained as Taoiseach, and Labour leader Dick Spring became Tánaiste and Minister for Foreign Affairs.

After less than two years the government fell in a controversy over the appointment of Attorney General, Harry Whelehan, as president of the High Court.[3] The parliamentary arithmetic had changed as a result of Fianna Fáil's loss of two seats in by-elections in June and Labour negotiated a new coalition, the first time in Irish political history that one coalition replaced another without a general election. Between 1994 and 1997 Fine Gael, the Labour Party, and Democratic Left governed in the so-called Rainbow Coalition. Dick Spring of Labour became Tánaiste and Minister for Foreign Affairs again.

Merger with Democratic Left

Labour presented the 1997 election, held just weeks after spectacular victories for the French Parti Socialiste and Tony Blair's New Labour, as the first-ever choice between a government of the left and one of the right, but the party, as had often been the case following its participation in coalitions, lost support and failed to retain half of its Dáil seats. A poor performance by Labour candidate Adi Roche in the subsequent election for President of Ireland led to Spring's resignation as party leader.

In 1997 Ruairi Quinn became the new Labour leader. Negotiations started almost immediately and in 1999 the Labour Party merged with Democratic Left, keeping the name of the larger partner.

21st century

Quinn resigned as leader in 2002 following the poor results for the Labour Party in the general election, when the Labour Party was returned with only 21 seats, the same number of seats as it had held before that general election. Former Democratic Left TD Pat Rabbitte became the new leader, the first to be elected directly by the members of the party.

In the 2004 European Parliament election, Proinsias De Rossa retained his seat for Labour in the Dublin constituency. This was Labour's only success in the election.

In 2004, Labour entered into an election pact in advance of the 2004 Local and European elections. Known as the "Mullingar Accord", and undertaken with Fine Gael,[115] a number of mutually acceptable and compatible policy documents were published in the lead up to the elections.

At the 2005 Labour Party conference in Tralee, a pre-election voting transfer pact was also endorsed with the Fine Gael party. This saw increased co-operation between the party leaders, Pat Rabbitte and the Fine Gael leader, Enda Kenny, as well as the party's front benches. The two parties formed the "Alliance for Change" in the run-up to the election and pursued joint policies and economic costings in some policy areas. However, though Fine Gael gained 20 seats in the election in 2007, Labour's vote continued to stagnate at 10.13%, a marginal decline from 2002 and it returned with 20 seats, one less than before.

Rabbitte resigned as leader in August 2007, a year ahead of his six-year term came to an end. Éamon Gilmore, TD for Dún Laoghaire, replaced Rabbitte, and expressed a preference for an independent strategy, emphasising the need for Labour to concentrate on itself, rather than following media interest in its alliance with other parties.

In the 2011 Irish general election, the Labour Party had its "best ever showing", winning 37 Dáil seats.[116] At the 2016 Irish general election, the party had the "worst election in its 104-year history", dropping from 37 seats to just 7.[116]

In the February 2020 Irish general election, this number fell to just 6 seats (4.4% of the popular vote), with longstanding TDs Joan Burton and Jan O'Sullivan losing their seats, and Longford-Westmeath being lost to the retirement of Willie Penrose. However, Labour improved upon this in the subsequent Seanad elections, winning 5 seats. New senators Mark Wall, Annie Hoey, Rebecca Moynihan and Marie Sherlock, as well as the re-election of Ivana Bacik made Labour the third largest party in the Seanad.

On the same day as the final count of voting in the Seanad elections on 3 April, Alan Kelly edged out Dáil colleague Aodhán Ó Ríordáin to become Labour leader in the 2020 Labour Party leadership election

Historical archives

The Labour Party donated its archives to the National Library of Ireland in 2012, and is catalogued under call number: MS 49,494.[117]

See also

- Labour Party (Ireland)

- Category:Labour Party (Ireland) politicians

References

Citations

- ↑ "Annual Report" (PDF). Irish Trades Union Congress. 1912. p. 12.

- 1 2 3 Labour Party 2011.

- 1 2 3 Labour Party (Ireland) at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ "Sheehan, Daniel Desmond ('D. D.') | Dictionary of Irish Biography". www.dib.ie. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- 1 2 "Labour Party | History, Ideology & Policies | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "O'Leary, Michael | Dictionary of Irish Biography". dib.ie. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ↑ Dimitri Almeida (2012). The Impact of European Integration on Political Parties: Beyond the Permissive Consensus. CRC Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-136-34039-0. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Party Constitution". labour.ie. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ↑ "Labour working hard to get all kinds of political refugees into its big tent". independent. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ↑ "Labour in Name Only". jacobinmag.com. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- 1 2 Purcell, Niamh. "Catholic Stakhanovites? Religion and the Irish Labour Party" (PDF).

- ↑ "The Starry Plough Flag – Irish Studies". irishstudies.sunygeneseoenglish.org. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ↑ Allen, Kieran (1995). Fianna Fail and Irish Labour Party: From Populism to Corporatism. Pluto P.

- ↑ "Sacred or secular?". BBC News. 12 January 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ↑ "Lord, Make Me Good – But Not Yet!". The Phoenix Magazine. 19 January 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ↑ "Labour working hard to get all kinds of political refugees into its big tent". independent. 22 August 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ↑ Huesker, Constantin (7 July 2014). Why are Ireland's Principal Political Parties so Similar?. GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-656-69178-5.

- ↑ Hug, C. (2016). The Politics of Sexual Morality in Ireland. Springer. ISBN 9780230597853.

- ↑ O'Connell, Hugh (25 August 2014). "It looks like Labour's next manifesto will commit to widening Ireland's abortion laws". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ↑ "Women's Rights and Catholicism in Ireland" (PDF). New Left Review.

- ↑ Clancy, Patrick (1995). Irish Society: Sociological Perspectives. Institute of Public Administration. ISBN 978-1-872002-87-3.

- ↑ McDonagh, Patrick (7 October 2021). Gay and Lesbian Activism in the Republic of Ireland, 1973-93. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-19748-0.

- ↑ Sinnott, Richard (1995). Irish Voters Decide: Voting Behaviour in Elections and Referendums Since 1918. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4037-5.

- ↑ Ní Choncubhair, Sinéad (2014). "Brendan Corish: a life in politics, 1945–1977". Saothar. 39: 33–43. ISSN 0332-1169. JSTOR 24897248.

- ↑ Moxon-Browne, Edward. "The Europeanisation of Political Parties: The Case of the Irish Labour Party" (PDF). Centre for European Studies (University of Limerick).

- ↑ "O'Carroll, Richard | Dictionary of Irish Biography". dib.ie. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ↑ Daly, O'Brien & Rouse 2012, p. 5.

- 1 2 Gallagher 1985, p. 68.

- ↑ "Partridge, William Patrick ('Bill') | Dictionary of Irish Biography". www.dib.ie. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ↑ "Carney, Winifred ('Winnie') | Dictionary of Irish Biography". www.dib.ie. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ↑ "Russell, George William ('Æ') | Dictionary of Irish Biography". www.dib.ie. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ↑ Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress (1918). Report of the Annual Congress, City Hall Waterford, 5–7 August 1918 and the Special Congress, Mansion House Dublin, November 1–2 1918 (PDF). Dublin: ILPTUC National Executive. p. 122. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ↑ Broderick, Marian (15 November 2012). Wild Irish Women: Extraordinary Lives from History. The O'Brien Press. ISBN 978-1-84717-461-1.

- ↑ "Labour, British radicalism and the First World War", Labour, British radicalism and the First World War, Manchester University Press, pp. 182–200, 26 February 2018, doi:10.7765/9781526109316/html, ISBN 978-1-5261-0931-6, retrieved 3 January 2024

- ↑ "The story of the Irish Citizen Army, 1913-1916 - Sean O'Casey | libcom.org". libcom.org. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- 1 2 "Centenary of the first meeting of Dáil Éireann - Padraig Yeates". The Irish Congress of Trade Unions. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ Maxwell, Nick (28 December 2015). "Bitter freedom: Ireland in a revolutionary world 1918–1923". History Ireland. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- 1 2 "Anti-conscription campaign Ireland's most complete, and bloodless, victory over British imperialism". The Irish Times. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ↑ "'A Declaration of War on the Irish People' The Conscription Crisis of 1918 – The Irish Story". Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ↑ "Irish citizens campaign against conscription by the British Government, 1918 | Global Nonviolent Action Database". nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- 1 2 3 "How the Cork Labour movement defined the struggle for Irish independence". University College Cork. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ↑ "Wholesale Excommunication: Catholic Writer Appeals to Archbishop". The Watchword of Labour. 13 December 1919. p. 1.

- ↑ Rising From the Ashes. Cork City Council

- ↑ Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress (August 1921). Official Report of Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh Annual Meeting (PDF). Dublin: ILP & TUC National Executive. pp. 17–19, 110–115. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ↑ Gallagher 1985, p. 71.

- ↑ Purséil, Niamh (13 June 2022). "Labour offered an alternative voice of peace as nation tore itself apart". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ↑ Kissane, Bill (7 July 2022). "How did the Civil War impact civil society?".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Allen, Kieran (1997). Fianna Fáil and Irish Labour: 1926 to the Present. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-0865-4.

- ↑ Gallagher 1985, pp. 73–74.

- 1 2 3 4 "Norton, William Joseph ('Bill') | Dictionary of Irish Biography". dib.ie. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ↑ Dictionary of Irish Biography entry for James Larkin https://www.dib.ie/biography/larkin-james-a4685

- ↑ "Larkin, James | Dictionary of Irish Biography". dib.ie. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ↑ Watts, Gerry (2017). "Delia Larkin and the game of 'House'". History Ireland. 25 (5): 36–38. ISSN 0791-8224. JSTOR 90014602.

- ↑ "Big Jim Larkin: Hero and Wrecker". History Ireland. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2021.