| 1911 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | February 19, 1911 |

| Last system dissipated | December 13, 1911 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Three |

| • Maximum winds | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 972 mbar (hPa; 28.7 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 9 |

| Total storms | 6 |

| Hurricanes | 3 |

| Total fatalities | >27 |

| Total damage | $3 million (1911 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The 1911 Atlantic hurricane season was a relatively inactive hurricane season, with only six known tropical cyclones forming in the Atlantic during the summer and fall. There were three suspected tropical depressions, including one that began the season in February and one that ended the season when it dissipated in December. Three storms intensified into hurricanes, two of which attained Category 2 status on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale. Storm data is largely based on the Atlantic hurricane database, which underwent a thorough revision for the period between 1911 and 1914 in 2005.

Most of the cyclones directly impacted land. A westward-moving hurricane killed 17 people and severely damaged Charleston, South Carolina, and the surrounding area in late August. A couple of weeks earlier, the Pensacola, Florida area had a storm in the Gulf of Mexico that produced winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) over land. The fourth storm of the season struck the coast of Nicaragua, killing 10 and causing extensive damage.

Season summary

The Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT) officially recognizes six tropical cyclones from the 1911 season. Only three attained hurricane status, with winds of 75 mph (121 km/h) or greater. The third hurricane of the season was the most intense storm, with a minimum central air pressure of 972 mbar (28.7 inHg). A week after its dissipation, another hurricane formed with wind speeds that matched the previous storm, but with unknown air pressure. Three weak tropical depressions developed and remained below tropical storm force; the first formed in February and the third in December. The first storm to reach tropical storm intensity developed on August 4, and the final tropical storm of the year dissipated on October 31.[1]

The early 1900s lacked modern forecasting and documentation. The hurricane database from these years is sometimes found to be incomplete or incorrect, and new storms are continually being added as part of the ongoing Atlantic hurricane reanalysis. The period from 1911 through 1914 was reanalyzed in 2005. Two previously unknown tropical cyclones were identified using records including historical weather maps and ship reports, and information on the known storms was amended and corrected.[2] These storms are referred to simply by their number in chronological order, since tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Ocean were not given official names until much later.[3]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 35,[4] below the 1911–1920 average of 58.7.[5] ACE is a metric used to express the energy used by a tropical cyclone during its lifetime. Therefore, a storm with a longer duration will have high values of ACE. It is only calculated at six-hour increments in which specific tropical and subtropical systems are either at or above sustained wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm intensity. Thus, tropical depressions are not included here.[4]

Timeline

Systems

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 4 – August 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); <1007 mbar (hPa) |

Identified by its lack of associated frontal boundaries and closed circulation center, the first tropical cyclone of the 1911 season formed on August 4 over southern Alabama in the United States.[2] At only tropical depression strength, it tracked eastward and emerged into the Atlantic Ocean the next day. Several days later, while located near Bermuda, the depression became a tropical storm and turned northeastward. The storm lasted several more days until dissipating on August 11.[1] The storm produced heavy rainfall on the Bermuda, but no gale-force winds were reported. The storm was unknown until the 2005 Atlantic hurricane database revision recognized it as a tropical storm.[2]

Hurricane Two

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 8 – August 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 982 mbar (hPa) |

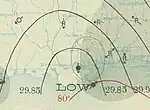

Based on ship observations in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico, a low-pressure area developed north of Key West in early August.[6] It developed into a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on August 8,[3] and strengthened into a tropical storm at 06:00 UTC on August 9 while moving northwestward off the west coast of Florida.[3] Gradual intensification continued, and at 06:00 UTC on August 11 the storm strengthened to hurricane status.[3] At 22:00 UTC on August 11, the hurricane reached its peak intensity and concurrently made landfall near the border between Alabama and Florida as a small tropical cyclone.[6] During this time, the storm's maximum sustained winds were estimated at 80 mph (130 km/h), making it the equivalent of a Category 1 hurricane on the modern day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.[3] A lull in the storm accompanied the nearby passage of its eye before conditions once again deteriorated.[7] Although the lowest barometric pressure measured on land was 1007 mbar (hPa; 29.74 inHg) in Pensacola, Florida, the storm's pressure was estimated to be much lower at 982 mbar (hPa: 29.00 inHg).[6] After making landfall, the hurricane weakened and slowly drifted westward, weakening to a tropical depression over Louisiana on August 13, before dissipating over Arkansas by 12:00 UTC the next day.[3]

While developing in the Gulf of Mexico, the tropical cyclone brought light rainfall to Key West, amounting to 1.82 in (46 mm) over two days.[8] The hurricane's outer rainbands affected the Florida panhandle as early as August 10, producing winds as strong as 80 mph (130 km/h) in Pensacola,[6] where it was considered the worst since 1906.[9] During the afternoon of August 11, the United States Weather Bureau issued storm warnings for coastal areas of the gulf coast where the hurricane was expected to impact.[10] Upon making landfall, the storm brought heavy precipitation, peaking at 10 in (250 mm) in Molino, Florida, although the heaviest rainfall was localized from Mississippi to central Alabama.[11] Some washouts occurred during brief episodes of heavy rain as the storm drifted westward after landfall.[10] Strong winds in the Pensacola area downed telecommunication lines and disrupted power,[12] cutting off communication to outside areas for 24 hours.[13] A pavilion on Santa Rosa Island had a third of its roof torn, and some other buildings inland were also unroofed. Offshore, twelve barges were grounded after being swept by the rough surf. Heavy losses were reported to timber after they were swept away when log booms failed.[9] Damage figures from the Pensacola area were conservatively estimated at US$12,600,[10] considered lighter than expected, although there were some deaths.[13]

Hurricane Three

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 23 – August 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 972 mbar (hPa) |

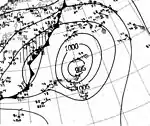

Over a week after the dissipation of the previous hurricane, the third storm of the season developed on August 23 and slowly tracked west-northwestward. After attaining hurricane status, the storm turned more towards the northwest, and several days later reached its peak wind speeds of 100 mph (155 km/h); a barometric pressure of 972 mbar (hPa) was reported.[1] The center passed inland a few miles north of Savannah, Georgia, on August 28; upon making landfall, the hurricane rapidly degenerated.[7] It deteriorated into a tropical depression on August 29 and persisted over land until dissipating a couple of days later.[1]

The hurricane, relatively small in size, caused widespread damage between Savannah and Charleston, South Carolina. Savannah itself received only minor damage, although the storm's center passed close by. Along the coast of Georgia, torrential rainfall caused numerous washouts on railroads. Crops, livestock and roads in the area took heavy damage. At Charleston, winds were estimated at 106 mph (171 km/h) after an anemometer, last reporting 94 mph (151 km/h), failed, and 4.90 in (124 mm) of precipitation fell over three days.[7]

The storm raged for more than 36 hours, causing severe damage;[14] the winds unroofed hundreds of buildings, demolished many houses and had an extensive impact on power and telephone services. Tides 10.6 ft (3.2 m) above normal left a "confused mass of wrecked vessels and damaged wharfs", according to a local forecaster in Charleston,[7] while six navy torpedo boats were ripped from their moorings and blown ashore.[15] In total, 17 people were killed in the hurricane, and property damage in Charleston was estimated at $1 million (1911 USD, $31.4 million 2014 USD).[7]

Hurricane Four

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 3 – September 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); <990 mbar (hPa) |

The next storm formed well to the east of the Lesser Antilles on September 3 and moved westward, attaining tropical storm status about a day later. The storm slowed and curved toward the southwest, nearing the northern coast of Colombia before pulling away from land and strengthening into a hurricane. It further intensified to Category 2 status before striking Nicaragua on September 10. Quickly weakening to a tropical storm, the cyclone continued westward across Central America and briefly entered the eastern Pacific Ocean. It dissipated shortly thereafter.[1] In the town of Corinto, a report indicated the deaths of 10 people and 50 additional injuries. About 250 houses were destroyed, leaving approximately $2 million (1911 USD, $62.8 million 2014 USD) in damage.[16] Data on this storm is extremely scarce; as such, only minor revisions could be made to its chronology in the hurricane database.[2]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 15 – September 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); <995 mbar (hPa) |

The fifth official tropical cyclone of the year was also previously unknown until contemporary reassessments. It exhibited some hybrid characteristics, and may have qualified for subtropical cyclone status according to the modern classification scheme.[2] On September 15, the storm formed over the central Atlantic and initially moved westward. It gradually intensified as it turned northwestward, and on September 19 it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone southeast of New England.[1] The system was subsequently absorbed by a more powerful frontal boundary approaching from the northwest.[2]

Tropical Storm Six

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 26 – October 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); <1006 mbar (hPa) |

The final storm was first observed as a disturbance near Puerto Rico in the Caribbean Sea in late October.[17] The disturbance was the precursor to a tropical depression which developed over the southern Bahamas and headed west-southwestward across Cuba,[1] where, at Havana, winds blew from the southeast at 44 mph (71 km/h).[17] It became a tropical storm on October 27 and drifted southwestward. Near the eastern tip of the Yucatán Peninsula, the storm turned sharply northward.[1] An area of high pressure over the United States prevented the cyclone from turning eastward toward Florida, and it continued into the Gulf of Mexico. However, on October 31, the storm curved eastward and moved ashore over northern Florida. The storm decreased in intensity as it passed into the Atlantic.[17] The storm's circulation center remained poorly defined throughout its course. It was long believed to have developed south of Cuba, although a reevaluation of ship data indicated the depression had actually formed east of the island.[2] On October 26, the Weather Bureau hoisted hurricane warnings along the east coast of Florida from Key West to West Palm Beach, and on the west coast up to Tampa.[18]

Tropical depressions

In addition to the six officially recognized tropical storms and hurricanes, three tropical depressions in the 1911 season have been identified. The first developed in February from a trough of low pressure in the open Atlantic and progressed westward. Although a ship dubiously reported winds of over 50 mph (80 km/h) in association with the system, a lack of supporting evidence precludes its designation as a tropical storm. The cyclone dissipated by February 21. The second depression evolved from an extratropical cyclone in mid- to late May, becoming a tropical cyclone on May 22 northeast of Bermuda. It persisted for three days as it meandered around the same general area before being absorbed by another non-tropical storm. The modern-day documentation of this system was also hindered by a lack of data. On December 11, the third tropical depression formed near the Turks and Caicos Islands. It progressed westward and was situated just north of eastern Cuba the next day. The system began to weaken on December 13 and dissipated shortly thereafter.[2]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hurricane Specialists Unit (2010). "Easy to Read HURDAT 1851–2009". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Landsea, Chris; et al. (2005). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT – 2005 Changes/Additions for 1911 to 1914". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. September 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ↑ Landsea, Christopher W.; et al. (May 15, 2008). "A Reanalysis of the 1911–20 Atlantic Hurricane Database" (PDF). Journal of Climate. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 21 (10): 2146. Bibcode:2008JCli...21.2138L. doi:10.1175/2007JCLI1119.1. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Landsea, Chris; et al. (April 2014). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reed, W. F. (August 1911). "The Small Hurricane of August 11–12, 1911 at Pensacola, FLA" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 39 (8): 1149–1150. Bibcode:1911MWRv...39.1149R. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1911)39<1149:TSHOAA>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0493. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ↑ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. "Observations for 1911 Storm #2" (.xls). Raw Tropical Storm/Hurricane Observations. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- 1 2 "Big Storm Hits State Of Florida". Morning Tribune. Altoona, Pennsylvania. August 11, 1911. p. 1. Retrieved 11 August 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 Reed, W.F. (August 1911). "The Small Hurricane Of August 11–12, 1911, At Pensacola, FLA" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 39 (8): 1149–1151. Bibcode:1911MWRv...39.1149R. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1911)39<1149:TSHOAA>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ↑ Schoner, R.W.; Molansky, S. Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (And Other Tropical Disturbances) (PDF) (Report). United States Weather Bureau's National Hurricane Research Project. p. 81. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ↑ "Pensacola Is Cut Off World By Storm". The Indianapolis News. Vol. 42, no. 114. Indianapolis, Indiana. August 12, 1911. p. 1. Retrieved 11 August 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Pensacola Storm Loss Big.; No Lives Lost in City, but Much Damage to Property". The New York Times. August 13, 1911. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Charleston in Grip of Fatal Hurricane; At Least Seven Lives Taken and $1,000,000 Damage Done by Wind and Water". The New York Times. August 29, 1911. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Wind Hurls Ships Ashore Like Toys". The Nevada Daily. August 30, 1911. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ↑ Bowe, Edward H (September 1911). "Weather, Forecasts and Warnings for the Month" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 39 (9): 1453. Bibcode:1911MWRv...39.1453B. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1911)39<1453:WFAWFT>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0493. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Frankenfield, H. C. (October 1911). "Weather, Forecasts and Warnings, October, 1911" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 39 (10): 1617–1620. Bibcode:1911MWRv...39.1617F. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1911)39<1617:WFAWO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Hurricane Off Florida Coast" (PDF). The New York Times. October 26, 1911. Retrieved March 3, 2011.