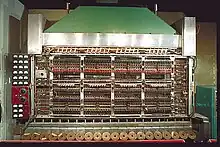

The IAS machine an early computer on display at the Smithsonian Institution | |

| Developer | John von Neumann |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) |

| Release date | June 10, 1952 |

| Lifespan | 1952–1958 |

| CPU | 1,700 vacuum tubes |

| Memory | 1,024 words (5.1 kilobytes) (Williams tubes) |

| Mass | 1,000 pounds (450 kg) |

| Computer architecture bit widths |

|---|

| Bit |

| Application |

| Binary floating-point precision |

| Decimal floating-point precision |

The IAS machine was the first electronic computer built at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, New Jersey. It is sometimes called the von Neumann machine, since the paper describing its design was edited by John von Neumann, a mathematics professor at both Princeton University and IAS. The computer was built under his direction, starting in 1946 and finished in 1951.[1] The general organization is called von Neumann architecture, even though it was both conceived and implemented by others.[2] The computer is in the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History but is not currently on display.[3]

History

Julian Bigelow was hired as chief engineer in May 1946.[4] Hewitt Crane, Herman Goldstine, Gerald Estrin, Arthur Burks, George W. Brown and Willis Ware also worked on the project.[5] The machine was in limited operation in the summer of 1951 and fully operational on June 10, 1952.[6][7][8] It was in operation until July 15, 1958.[9]

Description

The IAS machine was a binary computer with a 40-bit word, storing two 20-bit instructions in each word. The memory was 1,024 words (5 kilobytes in modern terminology). Negative numbers were represented in two's complement format. It had two general-purpose registers available: the Accumulator (AC) and Multiplier/Quotient (MQ). It used 1,700 vacuum tubes (triode types: 6J6, 5670, 5687, a few diodes: type 6AL5, 150 pentodes to drive the memory CRTs, and 41 CRTs (type: 5CP1A): 40 used as Williams tubes for memory plus one more to monitor the state of a memory tube).[10] The memory was originally designed for about 2,300 RCA Selectron vacuum tubes. Problems with the development of these complex tubes forced the switch to Williams tubes.

It weighed about 1,000 pounds (450 kg).[11]

It was an asynchronous machine, meaning that there was no central clock regulating the timing of the instructions. One instruction started executing when the previous one finished. The addition time was 62 microseconds and the multiplication time was 713 microseconds.

Although some claim the IAS machine was the first design to mix programs and data in a single memory, that had been implemented four years earlier by the 1948 Manchester Baby.[12] The Soviet MESM also became operational prior to the IAS machine.

Von Neumann showed how the combination of instructions and data in one memory could be used to implement loops, by modifying branch instructions when a loop was completed, for example. The requirement that instructions, data and input/output be accessed via the same bus later came to be known as the Von Neumann bottleneck.

IAS machine derivatives

Plans for the IAS machine were widely distributed to any schools, businesses, or companies interested in computing machines, resulting in the construction of several derivative computers referred to as "IAS machines", although they were not software compatible.[5]

Some of these "IAS machines" were:[13]

- AVIDAC (Argonne National Laboratory)

- BESK (Stockholm)

- BESM (Moscow)[5]

- Circle Computer (Hogan Laboratories, Inc.),[14][15][16] 1954[17][18]

- CYCLONE (Iowa State University)

- DASK (Regnecentralen, Copenhagen 1958)

- GEORGE (Argonne National Laboratory)

- IBM 701 (19 installations)

- ILLIAC I (University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign)

- JOHNNIAC (RAND)

- MANIAC I (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

- MISTIC (Michigan State University)

- ORACLE (Oak Ridge National Laboratory)

- ORDVAC (Aberdeen Proving Ground)

- PERM (Munich)[19]

- SARA (SAAB)

- SEAC (Washington, D.C.)[19]

- SILLIAC (University of Sydney)

- SMIL (Lund University)

- TIFRAC (Tata Institute of Fundamental Research)

- WEIZAC (Weizmann Institute)

See also

References

- ↑ "The IAS Computer, 1952". National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ Deepali A.Godse; Atul P.Godse (2010). Computer Organization. Technical Publications. pp. 3–9. ISBN 978-81-8431-772-5.

- ↑ Smithsonian IAS webpage

- ↑ John Markoff (February 22, 2003). "Julian Bigelow, 89, Mathematician and Computer Pioneer". The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 "Electronic Computer Project". Institute for Advanced Study. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ↑ Goldstein, Herman (1972). The Computer: From Pascal to von Neumann. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 317–318. ISBN 0-691-02367-0.

- ↑ Macrae, Norman (1999). John Von Neumann: The Scientific Genius who Pioneered the Modern Computer, Game Theory, Nuclear Deterrence, and Much More. American Mathematical Soc. p. 310. ISBN 9780821826768.

- ↑ "Automatic Computing Machinery: News - Institute for Advanced Study". Mathematics of Computation. 6 (40): 245–246. Oct 1952. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-52-99384-8. ISSN 0025-5718.

- ↑ Dyson, George (March 2003), "George Dyson at the birth of the computer", TED (Technology Entertainment Design) (Video), TED Conferences, LLC, archived from the original on 2012-03-17, retrieved 2012-03-21

- ↑ The history and development of the electronic computer project at the Institute for Advanced Study. Ware. 1953

- ↑ Weik, Martin H. (December 1955). "IAS". ed-thelen.org. A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems.

- ↑ "Manchester Baby Computer". Archived from the original on 2012-06-04.

- ↑ "The IAS computer family scrapbook | 102693640 | Computer History Museum". www.computerhistory.org. 2003. Retrieved 2018-05-23.

- ↑

- ↑ "Commercially Available General-Purpose Electronic Digital Computers of Moderate Price: THE CIRCLE COMPUTER".

- ↑ IAS type machine:

- "Automatic Computing Machinery: Technical Developments - THE CIRCLE COMPUTER". Mathematics of Computation. 7 (44): 249–255. 1953. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-53-99352-1. ISSN 0025-5718.

- ↑ Weik, Martin H. (Dec 1955). "CIRCLE". ed-thelen.org. A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems.

- ↑

- "COMPUTERS: 9. The Circle Computer". Digital Computer Newsletter. 6 (1): 5–6. Jan 1954.

- "COMPUTERS: 13. Circle Computer". Digital Computer Newsletter. 6 (3): 8–9. Jul 1954.

- 1 2 Turing's Cathedral, by George Dyson, 2012, p. 287

Further reading

- Gilchrist, Bruce, "Remembering Some Early Computers, 1948-1960", Columbia University EPIC, 2006, pp. 7–9. (archived 2006) Contains some autobiographical material on Gilchrist's use of the IAS computer beginning in 1952.

- Dyson, George, Turing's Cathedral, 2012, Pantheon, ISBN 0-307-90706-6 A book about the history of the Institute of Advanced Study around the making of this computer. Chapters 6 onward deal with this computer specifically.

- "Automatic Computing Machinery: Technical Developments - THE ELECTRONIC COMPUTER AT THE INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY". Mathematics of Computation. 7 (42): 108–114. 1953. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-53-99368-5. ISSN 0025-5718.

- "Documents related to IAS computer". www.bitsavers.org.

External links

- Oral history interviews concerning the Institute for Advanced Study—see also individual interviews with Willis H. Ware, Arthur Burks, Herman Goldstine, Martin Schwarzschild, and others. Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota.

- Ware, Willis H. (1953). The History and Development of the Electronic Computer Project at the Institute for Advanced Study (PDF). RAND.

- First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC – Copy of the original draft by John von Neumann

- Photos: JvN standing in front of IAS machine and another view of IAS machine from "CPSC 231 -- Mark Smotherman". people.cs.clemson.edu.