| Babanki | |

|---|---|

| Kejom, Finge | |

| Kəjòm[1] | |

| Native to | Cameroon |

| Region | Northwest |

| Ethnicity | Kejom |

Native speakers | 39,000 (2011)[2] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | bbk |

| Glottolog | baba1266 |

| ELP | Babanki |

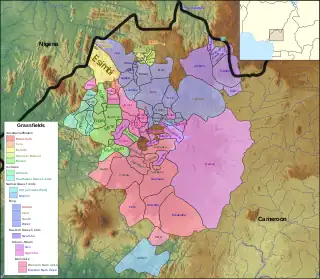

Linguistic map of the Grassfields languages of northwestern Cameroon. | |

Babanki, or Kejom (Babanki: Kəjòm [kɘ̀d͡ʒɔ́m]), is a Bantoid language that is spoken by the Babanki people of the Western Highlands of Cameroon.

Geography and classification

Babanki is a member of the Center Ring subfamily of the Grassfields languages, which is in turn a member of the extensive Southern Bantoid subfamily of the Atlantic-Congo branch of the hypothetical Niger-Congo language family.

According to Ethnologue, there were 39,000 speakers of Babanki as of 2011, although the Endangered Languages Project states that the 39,000 figure represents the ethnic population while actual speakers of the language number around 20,000.[3]

It is mainly spoken in the villages of Kejom Ketinguh and Kejom Keku (also known as Babanki Tungo and Big Babanki, respectively),[4][5] which are located in the Mezam department of the Northwest region of Cameroon. Languages spoken nearby include the closely related Ring languages Kom, Vengo, and Nsei to the east, and the more distantly related Eastern Grassfields languages Bafut, Mbili-Mbui, and Awing to the west. English, in particular Cameroonian Pidgin English, is commonly spoken as well, to the extent that the latter is beginning to replace Babanki in all domains, including the home.[5] Additionally, some speakers may speak French, Cameroon's other official language besides English, and speakers living in Kejom Keku may also speak the nearby Kom language, depending on their level of interaction with the Kom community.[5]

It has two main varieties, based on the two villages it is spoken in. They exhibit slight phonetic, phonological, and lexical differences but are mutually intelligible.[5] A distinct variety spoken by some members of a group of ethnic Fula who live in the hills surrounding Kejom Ketinguh has also been attested.[6]

Phonology

Consonants

Babanki has 25 consonant phonemes. Most consonants also appear in phonemic prenasalized, labialized, and palatalized forms, although it remains ambiguous as to whether Babanki actually has these secondary articulations or if they are simply consonant clusters of simple consonants with placeless nasals, /w/, or /j/, respectively.[5]

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Labial- velar |

Velar | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | b | t | d | k | ɡ | |||||||||

| Affricate | p͡f | b͡v | t͡s | d͡z | t͡ʃ | d͡ʒ | ||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||||||||||

| Approximant | j | w | ɰ[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||

| Lateral approximant | l | |||||||||||||

Babanki has some allophonic palatalization before front vowels /i e/. The velar plosives /k g/ are realized as palatalized [kʲ gʲ], respectively, and the labial-velar approximant /w/ is realized as a labial-palatal approximant [ɥ]. This variation also applies to labialized consonants (e.g. /kʷì/→[kᶣì] "up"), although labialized bilabials and labiodentals retain labial-velar secondary articulation.

Prenasalized consonants in Babanki (all oral consonants but /v/ can appear as prenasalized) are realized in several ways depending upon the manner of articulation of the consonant in question. Preceding an obstruent and following a vowel, prenasalization is generally realized as a homorganic nasal stop (e.g. /kɘ̀ⁿt͡ʃík/→[kɘ̀ɲt͡ʃíʔ] "lid"), while preceding a sonorant and following a vowel, prenasalization is generally realized without full oral closure which tends to cause the preceding vowel to be nasalized (e.g. /fɘ̀ⁿʃìk/→[fɘ̃̀ʃìʔ] "grass beetle"). Additionally, when a prenasalized consonant is word initial and has no preceding vowel, the nasal portion is often audibly syllabic and using the low tone (e.g. /ⁿdɔ̏ŋ/→[ǹdɔ̏ŋ] "potato").

Vowels

Babanki has eight vowel phonemes contrasting in height, roundness, and backing. Length distinction and nasalization also occur non-contrastively. Babanki is unusual in that it contrasts both the rounded and the unrounded close central vowels and the close and close-mid central unrounded vowels.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ɨ • ʉ | u |

| Close-mid | e | ɘ | o |

| Open-mid | (ɛː)[lower-alpha 2] | (ɔː)[lower-alpha 2] | |

| Open | a |

In open syllables, vowels /e/ and /o/ are realized as close-mid [e] and [o], while in closed syllables they are realized as open-mid [ɛ] and [ɔ] (compare [àbé] "liver" and [bɛ̀ʔ] "snatch", [ɘ̀kó] "money" and [kɔ́ʔ] "chop").

Tone

Babanki has both lexical tone and grammatical tone. At the phonological level it is described as simply having a distinction between low /˨/ and high /˦/ tonemes,[5] although a number of derived surface tonal sequences have been observed. Rarely, contour tones can occur in non-derived environments.

| Name | Notation |

|---|---|

| High | ˦ |

| Downstepped high | ꜜ˦ |

| Mid | ˧ |

| Low | ˨ |

| Low falling | ˨˩ |

| High-mid falling | ˦˧ |

| High-low falling | ˦˨ |

| Low-high rising | ˨˦ |

The downstepped high and mid tones are phonetically identical, but are otherwise distinct; the downstepped high tone [ꜜ˦] occurs much more freely and creates a tone ceiling for successive high tones in the same tonal phrase, while the mid tone [˧] must precede a high tone and is restricted to a few specific environments.[7]

Phonotactics

Typically, Babanki words are composed of a CV(C) stem with optional (C)V prefixes and suffixes.[5] The stem-initial onset is where the majority of Babanki consonants occur exclusively;[lower-alpha 3] onsets of affixes and function words only permit the phonemes /t k f v s ʃ m n j ɰ/, and the only permissible coda consonants are /m n ŋ f s k/. Allophony is much more distinct in coda consonants; /k/ is realized as a glottal stop [ʔ], and rimes ending in the alveolar nasal /n/ whose nuclei are the non-high vowels /a e o/ (i.e. /an en on/) diphthongize, surfacing as [aɪ̯n~aɪ̯̃ ɛɪ̯n~ɛɪ̯̃ ɔɪ̯n~ɔɪ̯̃].[5]

Vowel coalescence is also quite significant in Babanki. It occurs in /Vɘ/ and /VCɘ/ sequences (excluding those where /C/ is /m/), where the final close-mid central unrounded vowel and (in the case of the latter) the coda consonant coalesce to a single phonetically long vowel [Vː], the quality of which cannot necessarily be determined by either vowel (although in /Vɘ/ sequences the phonetic long vowel is usually of the same quality as the phonemic first vowel). For example, the phrase [kɘ̀zɔ̀ː kɔ́m] "my speargrass" would be phonemically parsed:

Here, the sequence /ònɘ́/ coalesces into the long vowel [ɔː]. Although virtually all long vowels that occur in Babanki are due to this process, there are a few instances of long vowels that are not clearly derived, such as in the words [ɘ̀kɔ̀ː] "which" and [ⁿbɛ̀ː] "term of address for fon".[5]

Sample

| Phonetic transcription[lower-alpha 4] | Translation |

|---|---|

| ɘ̀fʷɔ́fꜜɘ́ gɘ̀ː kᶣì wɛ̂ː t͡ʃᶣìt͡ʃᶣì ǹtáŋmɘ́ lá à tóː ndɘ̀ t͡ʃòː ndɘ̀ ló sɘ́t͡sɛ̀ɪ̯n wùd͡ʒèʔ mû ɰ mɔ̀ʔ dàlɘ́ lɨ̀mtɘ́ vȉ

vwě ꜜɰʉ́mɘ́ lá ɥìʔ á ɰɘ́ t͡ʃòː mbȉ ɘ̀ nɘ̀ lá wùd͡ʒèʔ nájì t͡súʔ dàlɘ́ lɨ̀mtɘ́ː wɛ́ɪ̯n mwâ tóː wɛ́ɪ̯n t͡ʃòː wút͡sɛ́ɪ̯n ɘ̀fɔ́fꜜɘ́ gɘ̀ː kᶣìː mɘ̀ zìtɘ̀ sɘ̀ t͡ʃǒ nôː nàntô ɰɘ̌ lì t͡ʃǒː ɰɔ́ʔtɘ̀ wùd͡ʒèʔ jí bɔ̀ŋsɘ̀ fʷɔ́mtɘ̀ dàlɘ́ lɨ̀mtɘ́ː wɛ́ɪ̯n á wɛ́ː wɛ̏ɪ̯n kɘ̀ɲʉ̃ː kʲíkɘ́ ɰɔ́ʔ ɘ̀fʷɔ́fꜜɘ́ gɘ̀ː kᶣì ɰɘ̀ kʲé t͡ʃᶣìt͡ʃᶣǐː zìtɘ̀ báɪ̯n ɘ̀ lɨ̀mɘ̀ vȉ wùd͡ʒèʔ jí zàŋsɘ̀ t͡sùʔ dàlɘ́ lɨ̀mtɘ́ː wɛ́ɪ̯n kɘ́ t͡ʃòː ɘ̀fɔ́fꜜɘ́ gɘ̀ː kᶣì ɰɘ̀ bʲɨ́mɘ́ lá t͡ʃᶣìt͡ʃᶣǐː ꜜtóː t͡ʃòː jȉ |

The North Wind and the Sun were arguing about who was stronger than who, until a traveler wearing a warm gown came.

They agreed that the person who would first make the traveler take off his gown was stronger than the other. The North Wind then began to blow with great force. As he blew stronger, the traveler instead wrapped his warm gown around his body. This thing was too much, and the North Wind gave up. Then the Sun began to shine and make places hot, and the traveler quickly took off his gown. This surpassed the North Wind; he accepted that the Sun was stronger than him. |

| Phonemic transcription with interlinear gloss | |

ɘ̀-fʷóf C3-wind ɘ ASS.C3 gɘ̀ part ɘ̀ DIR kʷì above wénɘ̀ with t͡ʃʷìt͡ʃʷì sun(C1) ǹ-táŋmɘ́ PST-quarrel lá COMP à FOC tó-ɘ be.strong-PROG ndɘ̀ who t͡ʃò-ɘ pass-PROG ndɘ̀ who ló, EMPH sɘ́t͡sèn until wù-d͡ʒèk C1.NMLZ-travel mú while ɰɘ̀ 3SG.C1 mòk wear dálɘ̀ gown(C1) lɨ̀mtɘ́ hot vì. come The North Wind and the Sun were arguing about who was stronger than who, until a traveler wearing a warm gown came. vɘ̀wé 3PL.C2 ɰʉ́mɘ́ agree lá COMP ɥìk person(C1) á REL ɰɘ́ 3SG.C1 t͡ʃò-ɘ pass-PROG mbì first ɘ̀ CONJ nè cause lá COMP wù-d͡ʒèk C1.NMLZ-travel nájì DEM t͡súk remove dálɘ̀ gown(C1) lɨ̀mtɘ́ hot ɘ́ ASS.C1 wén 3SG.POSS.C1 mú so à FOC tó-ɘ be.strong-PROG wén 3SG.C1 t͡ʃò-ɘ pass-PROG wú-t͡sén. C1.NMLZ-certain They agreed that the person who would first make the traveler take off his gown was stronger than the other. ɘ̀-fʷóf C3-wind ɘ ASS.C3 gɘ̀ part ɘ̀ DIR kʷì above ɘ́ SUBJ.C3 mɘ̀ then zìtɘ̀ start sɘ̀ PRS t͡ʃò-ɘ pass-PROG nókɘ̀ really nàntô. much The North Wind then began to blow with great force. ɰɘ̀ 3SG.C3 ɘ́ SUBJ.C3 lì so t͡ʃò-ɘ pass-PROG ɰóktɘ̀ be.big wù-d͡ʒèk C1.NMLZ-travel jí DEM bòŋsɘ̀ instead fʷómtɘ̀ fold dálɘ̀ gown(C1) lɨ̀mtɘ́ hot ɘ́ ASS.C1 wén 3SG.POSS.C1 á to wén 3SG.POSS.C3 ɘ̀-wén. C3-body As he blew stronger, the traveler instead wrapped his warm gown around his body. kɘ̀-ɲʉ́ C7-thing ɘ̀ ASS.C7 kí-kɘ́ this-C7 ɰɔ́k be.big ɘ̀-fʷóf C3-wind ɘ ASS.C3 gɘ̀ part ɘ̀ DIR kʷì above ɰɘ̀ 3SG.C3 ké. allow This thing was too much, and the North Wind gave up. t͡ʃʷìt͡ʃʷì sun(C1) zìtɘ̀ start bán shine ɘ̀ CONJ lɨ̀mɘ̀ hot-PROG vì come wù-d͡ʒèk C1.NMLZ-travel jí DEM zàŋsɘ̀ hurry t͡sùk remove dálɘ̀ gown(C1) lɨ̀mtɘ́ hot ɘ́ ASS.C1 wén. 3SG.POSS.C1 Then the Sun began to shine and make places hot, and the traveler quickly took off his gown. kɘ́ 3SG.C7 t͡ʃò pass ɘ̀-fʷóf C3-wind ɘ ASS.C3 gɘ̀ part ɘ̀ DIR kʷì above ɰɘ̀ 3SG.C3 bʲɨ́mɘ́ accept lá COMP t͡ʃʷìt͡ʃʷì sun(C1) ɘ́ SUBJ.C1 tó-ɘ be.strong-PROG t͡ʃò-ɘ pass-PROG jì. 3SG.C3 This surpassed the North Wind; he accepted that the Sun was stronger than him. | |

Linguistic studies

Linguistic research has been conducted in the Babanki community since the late 1970s. SIL Cameroon and the Cameroon Association for Bible Translation and Literacy (CABTAL) have been actively engaged with the Babanki language and community since 1988 and 2004, respectively.[4]

Babanki phonology

Akumbu, Pius W. (1999). Nominal phonological processes in Babanki (MA thesis). University of Yaoundé.

Hyman, Larry M. (July 1979). "Tonology of the Babanki noun". Studies in African Linguistics. 10 (2): 159–178.

Mutaka, Ngessimo M.; Phubon Chie, Esther (2006). "Vowel raising in Babanki". Journal of West African Languages. 33 (1): 71–88.

Phubon, Esther (1999). Aspects of Babanki phonology (BA thesis). University of Buea.

Phubon, Esther (2002). Phonology of the Babanki verb (MA thesis). University of Buea.

Phubon, Esther (2007). Lexical phonology of Babanki (DEA thesis). University of Yaoundé I.

Phubon, Esther (2014). Phrasal phonology of Babanki: An outgrowth of other components of the grammar (PhD thesis). University of Yaoundé I.

Tamanji, Pius N. (1987). Phonology of Babanki (MA thesis). University of Yaoundé.

Babanki grammar

Akumbu, Pius W. (2008). Blench, Roger M. (ed.). Kejom (Babanki) – English lexicon. KWEF Kay Williamson Educational Foundation – Languages Monographs: Local Series. Vol. 2. ISBN 978-3-89645-782-0.

Akumbu, Pius W. (2009). "Kejom tense system.". In Tanda, Vincent; Tamanji, Pius; Jick, Henry Jick (eds.). Language, literature and social discourse in Africa: Essays in honor of Emmanuel N. Chia. Buea: University of Buea. pp. 183–200.

Akumbu, Pius W.; Chibaka, Evelyn Fogwe (2012). A pedagogic grammar of Babanki. GA Grammatical Analyses of African Languages. Vol. 42. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

Fungeh Abongkeyung Landeà. (2022). Babanki for beginners.

Babanki sociolinguistics

Brye, Edward (2001). Rapid Appraisal Sociolinguistic Research Among the Babanki (PDF). ALCAM. Vol. 824. Yaoundé: SIL. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-07.

Notes

- ↑ Also transcribed as [ɣ] by some researchers.

- 1 2 The long open-mid vowels /ɛː/ and /ɔː/ are only marginally phonemic.

- ↑ A notable exception to this is the consonants /j/ and /v/, which only appear in the onsets of a few stems but are relatively common in affixes and function words.

- ↑ In this passage, the low falling tone [˨˩] is transcribed using the diacritic for extra low tone, e.g. [ȅ]

Further reading

- Faytak, Matthew and Akumbu, Pius W. (2021). "Kejom (Babanki)". Illustrations of the IPA. Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 51 (2): 333–354. doi:10.1017/S0025100319000264

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link), with supplementary sound recordings.

References

- ↑ Keyeh, Emmanuel (2007). Dzàŋ bè nyòˀ gàˀa Kəjòm (Read and also write the Kejom language). Yaounde, Republic of Cameroon: CABTAL.

- ↑ Babanki at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ↑ "Babanki". Endangered Languages Project.

- 1 2 Akumbu, Pius W. (2018-03-19). "Babanki literacy classes and community-based language research". Insights from Practices in Community-Based Research (PDF). De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 266–279. doi:10.1515/9783110527018-015. ISBN 978-3-11-052701-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Faytak, Matthew; Akumbu, Pius W. (August 2021). "Kejom (Babanki)". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 51 (2): 333–354. doi:10.1017/S0025100319000264. S2CID 235915107.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ↑ Akumbu, Pius W.; Asonganyi, Esther P. (December 2010). "Language in Contact: The Case of the Fulɓe Dialect of Kejom (Babanki)". African Study Monographs. 31 (4): 173–187. doi:10.14989/139265.

- ↑ Hyman, Larry H. (July 1979). "Tonology of the Babanki Noun". Studies in African Linguistics. 10 (2): 159–178.

External links

- ELAR archive of Multimedia Documentation of Babanki Ritual Speech

- Kejom-English Dictionary app for Android on the Google Play Store