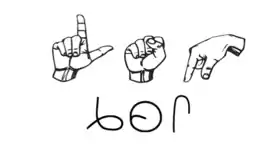

| Quebec Sign Language (LSQ) | |

|---|---|

| Langue des signes québécoise | |

| |

| Native to | Canada |

| Region | Quebec, parts of Ontario and New Brunswick. Some communities within francophone groups in other regions of Canada. |

Native speakers | 990 (2021)[1] L2 speakers: 6,195[1] |

| none si5s, ASLwrite | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | none |

Recognised minority language in | Ontario only in domains of: legislation, education and judiciary proceedings[2]

Government of Canada only on federal level, as a primary language of deaf persons in Canada [3] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | fcs |

| Glottolog | queb1245 |

| ELP | Quebec Sign Language |

Quebec Sign Language, known in French as Langue des signes québécoise or Langue des signes du Québec (LSQ), is the predominant sign language of deaf communities used in francophone Canada, primarily in Quebec. Although named Quebec sign, LSQ can be found within communities in Ontario and New Brunswick as well as certain other regions across Canada. Being a member of the French Sign Language family, it is most closely related to French Sign Language (LSF), being a result of mixing between American Sign Language (ASL) and LSF. As LSQ can be found near and within francophone communities, there is a high level of borrowing of words and phrases from French, but it is far from creating a creole language. However, alongside LSQ, signed French and Pidgin LSQ French exist, where both mix LSQ and French more heavily to varying degrees.

LSQ was developed around 1850[4] by certain religious communities to help teach children and adolescents in Quebec from a situation of language contact. Since then, after a period of forced oralism, LSQ has become a strong language amongst Deaf communities within Quebec and across Canada. However, due to the glossing of LSQ in French and a lack of curriculum within hearing primary and secondary education, there still exist large misconceptions amongst hearing communities about the nature of LSQ and sign languages as a whole, which negatively impacts policy making on a larger scale.

History

In the mid-1800s, Catholic priests took the existing LSF and ASL and combined the two to promote education of deaf children and adolescents. Several decades later, under the influence of Western thought, oralism became the primary mode of instruction in Quebec and the rest of North America. There, students were subjected to environments that discouraged and often outright banned LSQ use, instead promoting the use of whatever residual hearing the student had if any.[5] Such an approach had varying effects where audism lead to lower literacy rates as well as lower rates of language acquisition seen in children sent to residential schools at an early age.[6][7]

Around the 1960s, several schools for the Deaf were established in Montreal in response to the failed audistic education: Montreal Institute for the Deaf and Mute, Institution des Sourdes-Muettes, Institut des Sourds de Charlesbourg, none of which exist any longer. However, the MacKay School for the Deaf has existed since 1869 serving the anglophone and ASL-speaking communities in Montreal. Since the 1960s, there has been a growing population of LSQ speakers in Quebec and spreading across Canada. Due to the close nature of French and LSQ, Deaf members of francophone communities tend to learn LSQ even though ASL tends to be the majority language around those communities.[8] In 2007, Ontario passed legislation making it the only region in Canada that recognized LSQ in any capacity, noting that "The Government of Ontario shall ensure that [ASL, LSQ and First Nations Sign Language] may be used in the courts, in education and in the Legislative Assembly."[2]. In 2019, Canada passed federal legislature which recognized ASL, LSQ, and Indigenous sign languages as the primary languages for communication by deaf persons in Canada." This new legislature established the requirement of all federal information and services to be available in these languages.[3]

There have been calls to modify Quebec's Charter of the French Language to include provisions for LSQ. However, all bills have been rejected for one reason or another leaving the status of LSQ up in the air for Quebec and the rest of Canada.

Official status

LSQ is recognized as an official language in Ontario only in domains of education, legislation and judicial activities after the passing of Bill 213 within the Ontario Legislative Assembly. Across the rest of Canada, there is no protection or oversight for the language as neither federal, provincial nor territorial governments recognize LSQ as a language other than Ontario.

In Quebec in 2002 following the passing of Bill 104, recommendations presented to Commission of the Estates-General were rejected. In 2013, the Québec Cultural Society for the Deaf presented additional recommendations during discussions on the update of Bill 14 which would ultimately modify the Charter of the French Language. Three recommendations were proposed modifying the Charter such that LSQ is recognized along the same lines as done for the language and culture of North American Aboriginal Peoples and the Inuit of Quebec. The first was noting that LSQ is the primary language of communication for Deaf Quebecois, the second that deaf youths be taught bilingually (French/LSQ) in all cadres of education and the third that French be rendered accessible to all d/Deaf people within the province. Bill 14 was never voted on by the National Assembly due to the minority party being unable to amass enough support from other parties.[9]

Population

The population of any sign-language-speaking community is difficult to ascertain due to a variety of factors, namely imprecise census data and lack of connection with the communities themselves. The same is true in Canada with LSQ speakers where census data through StatsCan captures basic information that renders comprehension of the situation difficult as the numbers do not accurately portray the language population. StatsCan reports as of 2011 just 455 speakers of LSQ, however it is estimated that 2.6% (or 5,030 people) of Quebec’s population possessed hearing deficiency.

Geographic distribution

LSQ is used primarily within Quebec. Outside, the largest communities of LSQ users are in Sudbury, Ottawa and Toronto with smaller notable communities in parts of New Brunswick. Additionally, LSQ can be found in francophone communities across the country, but no real data has been collected on hard numbers.

In Montreal, LSQ is displaced in certain areas by ASL where it co-habitates. Generally, ASL can be found in anglophone communities, however it is not uncommon to meet people bilingual in ASL and LSQ in much the same way one would meet a bilingual English-French person. While ASL is growing within Montreal, LSQ is still a strong language in the city, supported by speakers from across the province.

See also

References

- 1 2 Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2022-02-09). "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - Canada [Country]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- 1 2 Province of Ontario (2007). "Bill 213: An Act to recognize sign language as an official language in Ontario". Archived from the original on 2018-12-24. Retrieved 2015-07-22.

- 1 2 Naef, B.; Perez-Leclerc, M. (2019). "Legislative Summary of Bill C-81: An Act to ensure a barrier-free Canada".

- ↑ Frenette, Agathe (1 September 2007). "Tribune : La langue des signes québécoise" (in French). Archived from the original on 11 March 2016.

- ↑ Gallaudet University. "Oral Schools". Archived from the original on 2013-07-07. Retrieved 2015-07-22.

- ↑ Jinx. "Residential Schools for the Deaf".

- ↑ Reach Canada. "Educational Abuse in Residential Schools for the Deaf". Archived from the original on 2016-01-11. Retrieved 2015-07-22.

- ↑ Office des personnes handicapées du Québec (1 November 2014). "La reconnaissance officielle des langues des signes : état de la situation dans le monde et ses implications" (PDF) (in French).

- ↑ Assemblée Nationale du Québec (2013). "Projet de loi n°14 : Loi modifiant la Charte de la langue française, la Charte des droits et libertés de la personne et d'autres dispositions législatives".

External links

- Centre de Communication Adaptée (in French)

- Office des personnes handicapées (in French)