| Lusitanian | |

|---|---|

One of the inscriptions of Arroyo de la Luz | |

| Native to | Inland central-west Iberian Peninsula |

| Region | Beira Alta, Beira Baixa and Alto Alentejo Portugal and Extremadura and part of province of Salamanca Spain |

| Extinct | 2nd century AD |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xls |

xls | |

| Glottolog | lusi1235 |

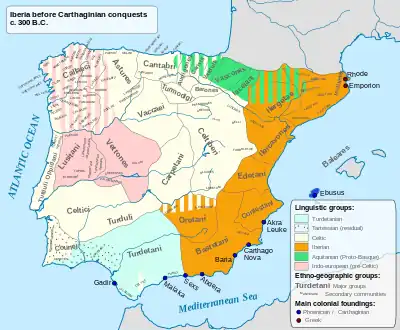

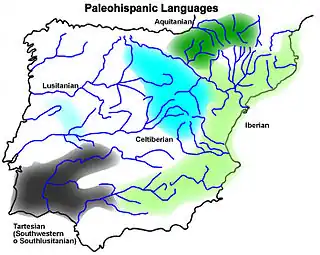

Lusitanian (so named after the Lusitani or Lusitanians) was an Indo-European Paleohispanic language. There has been support for either a connection with the ancient Italic languages[1][2] or Celtic languages.[3][4] It is known from only six sizeable inscriptions, dated from c. 1 CE, and numerous names of places (toponyms) and of gods (theonyms). The language was spoken in the territory inhabited by Lusitanian tribes, from the Douro to the Tagus rivers, territory that today falls in central Portugal and western Spain.[5]

Classification and related languages

Celtic

Scholars like Untermann[6] have identified toponymic and anthroponymic radicals which are clearly linked to Celtic materials: briga ‘hill, fortification’, bormano ‘thermal’ (Cf. theonym Bormo), karno ‘cairn’, krouk ‘hillock, mound’, crougia ‘monument, stone altar’, etc. Others, like Anderson,[7] after inscriptional materials of Lusitania, and Gallaecia have been under closer scrutiny, with the results suggesting albeit somewhat indirectly; believe that Lusitanian and Gallaecian formed a fairly homogeneous linguistic group displaying closely affiliated inscriptions.[8] Indigenous divine names in Portugal and Galicia frequently revolve around the gods or goddesses Bandu (or Bandi), Cossu, Nabia and Reve:

- Bandei Brialcacui (Beira-Baixa)

- Coso Udaviniago (A Coruña)

- Cosiovi Ascanno (Asturias)

- deo domeno Cusu Neneoeco (Douro)

- Reo Paramaeco (Lugo)

- Reve Laraucu (Ourense)

- Reve Langanidaeigui (Beira-Baixa)

The Lusitanian and Gallaecian divine name Lucubos, for example, also occurs outside the peninsula, in the plural, in Celtic Helvetia, where the nominative form is Lugoves. Lug was also an Irish god, and the ancient name of Lyon was Lug dunum and may have a connection with the Lusitanian and Gallaecian word, suggesting therefore a north-western Iberian sprachbund with Lusitanian as a dialect, not a language isolate.[9] Prominent linguists such as Ellis Evans believe that Gallaecian-Lusitanian were one same language (not separate languages) of the “P” Celtic variant.[10][11]

While chronology, migrations and diffusion of Hispanic Indo-European peoples are still far from clear, it has been argued there is a case for assuming a shared Celtic dialect for ancient Portugal and Galicia-Asturias. Linguistic similarities between these Western Iberian Indo-Europeans, the Celtiberians, the Gauls and the Celtic peoples of Great Britain indicate an affiliation in vocabulary and linguistic structure.[8]

Furthermore, scholars such as Koch say there is no unambiguous example of the reflexes of the Indo-European syllabic resonants *l̥, *r̥, *m̥, *n̥ and the voiced aspirate stops *bʱ, *dʱ, *ɡʱ.[5] Additionally, names in the inscriptions can be read as undoubtedly Celtic, such as AMBATVS, CAELOBRIGOI and VENDICVS.[5] Dagmar Wodtko argues that it is hard to identify Lusitanian personal or place-names that are actually not Celtic.[12] These arguments contradict the hypothesis that the p- in PORCOM alone excludes Lusitanian from the Celtic group of pre-Roman languages of Europe[13] and that it can be classed as a Celtic dialect but one that preserved Indo-European *p (or possibly an already phonetically weakened [ɸ], written P as an archaism).[5][14][15] This is based largely on numerous Celtic personal, deity, and place names.[16][17]

Lusitanian possibly shows /p/ from Indo-European *kʷ in PVMPI, pronominal PVPPID from *kʷodkʷid,[18] and PETRANIOI derived from *kʷetwor- 'four',[19] but that is a feature found in many Indo-European languages from various branches (including P-Celtic/Gaulish, Osco-Umbrian, and partially in Germanic where it subsequently evolved into /f/, but notably not Celtiberian), and by itself, it has no bearing on the question of whether Lusitanian is Celtic.[20] Bua Carballo suggests that pairings on different inscriptions such as Proeneiaeco and Proinei versus Broeneiae, and Lapoena versus Laboena, may cast doubt on the presence of a P sound in Lusitanian.[21]

Para-Celtic

Some scholars have proposed that it may be a para-Celtic language, which evolved alongside Celtic or formed a dialect continuum or sprachbund with Tartessian and Gallaecian. This is tied to a theory of an Iberian origin for the Celtic languages.[22][23][24] It is also possible that the Q-Celtic languages alone, including Goidelic, originated in western Iberia (a theory that was first put forward by Welsh historian Edward Lhuyd in 1707) or shared a common linguistic ancestor with Lusitanian.[25]

Secondary evidence for this hypothesis has been found in research by biological scientists, who have identified (firstly) deep-rooted similarities in human DNA found precisely in both the former Lusitania and Ireland[26][27] and (secondly) the so-called "Lusitanian distribution" of animals and plants unique to western Iberia and Ireland. Both of these phenomena are now generally believed to have resulted from human emigration from Iberia to Ireland during the late Paleolithic or early Mesolithic eras.[28]

Non-Celtic

In general, philologists consider Lusitanian to be an Indo-European language, but not Celtic.[29]

Villar and Pedrero (2001) propose a connection between Lusitanian and contemporaneous ancient Ligurian, which was spoken mostly in north-west Italy, between the Gaulish and Etruscan sprachraums). There are two major, unresolved lacunae in this hypothesis. Firstly, Ligurian remains unclassified and is usually considered to be either Celtic,[30] or "Para-Celtic", which does not resolve the question of dissimilarities between Lusitanian and canonical Celtic languages (including Iberoceltic). Secondly, the hypothesis is based partly on shared grammatical elements, parallels in theonyms and possible cognate lexemes, between Lusitanian and third languages that have no known connection to Ligurian, such as Umbrian, an Italic language. (Villar and Pedrero report possible cognates including e.g. Lusitanian comaim and Umbrian gomia.[2]) It is therefore at least as likely that Lusitanian had a closer connection to Italic languages (than it did to Ligurian).

Krzysztof (1999) is highly critical of the name-correspondences of Lusitanian and Celtic by Anderson (1985) and Untermann (1987), describing them as "unproductive" and agrees with Karl Horst Schmidt that they are insufficient proof of a genetic relationship because they could have come from language contact [with Celtic]. He concludes that Lusitanian is an Indo-European language, likely of a western but non-Celtic branch, as it differs from Celtic speech by some phonological phenomena, e.g. in Lusitanian Indo-European *p is preserved but Indo-European *d is changed into r; Common Celtic, on the contrary, retains Indo-European *d and loses *p.[31]

Jordán Colera (2007) does not consider Lusitanian or more broadly Gallo-Lusitanian, as a Celtic corpus, although he claims it has some Celtic linguistic features.[32]

According to Prósper (1999), Lusitanian cannot be considered a Celtic language under existing definitions of linguistic celticity because, along with other non-Celtic features, it retains Indo-European *p in positions where Celtic languages would not, specifically in PORCOM 'pig' and PORGOM.[33] More recently, Prósper (2021) has confirmed her earlier readings of inscriptions with the help of a newly discovered inscription from Plasencia, showing clearly that the morphs of the dative and locative endings definitely separates Lusitanian from Celtic and approaches it to Italic.[34][35]

Prósper (1999) argues that Lusitanian predates the arrival of Celtic in the Iberian Peninsula and points out that it retains elements of Old European, making its origins possibly even older.[36] This provides some support to the proposals of Mallory and Koch et al., who have postulated that the ancient Lusitanians originated from either Proto-Italic or Proto-Celtic speaking populations who spread from Central Europe into Western Europe after new Yamnaya migrations into the Danube valley, while Proto-Germanic and Proto-Balto-Slavic may have developed east of the Carpathian Mountains, in present-day Ukraine,[37] moving north and spreading with the Corded Ware culture in Middle Europe (third millennium BCE).[38][39] Alternatively, a European branch of Indo-European dialects, termed "North-west Indo-European" and associated with the Beaker culture, may have been ancestral to not only Italic and Celtic but also Germanic and Balto-Slavic.[40]

Luján (2019) follows a similar line of thought but places the origin of Lusitanian even earlier. He argues that the evidence shows that Lusitanian must have diverged from the other western Indo-European dialects before the kernel of what would then evolve into the Italic and Celtic language families had formed. This points to Lusitanian being so ancient that it predates both the Celtic and Italic linguistic groups. Contact with subsequent Celtic migrations into the Iberian Peninsula are likely to have led to the linguistic assimilation of the Celtic elements found in the language.[41]

Geographical distribution

Inscriptions have been found Cabeço das Fráguas (in Guarda), in Moledo (Viseu), in Arroyo de la Luz (in Cáceres) and most recently in Ribeira da Venda. Taking into account Lusitanian theonyms, anthroponyms and toponyms, the Lusitanian sphere would include modern northern Portugal and adjacent areas in southern Galicia,[43] with the centre in Serra da Estrela.

The most famous inscriptions are those from Cabeço das Fráguas and Lamas de Moledo in Portugal and Arroyo de la Luz in Spain. Ribeira da Venda is the most recently discovered (2008).

A bilingual Lusitanian–Latin votive inscription is reported to attest the ancient name of Portuguese city of Viseu: Vissaîegobor.[44]

Writing system

All the known inscriptions are written in the Latin alphabet, which was borrowed by bilingual Lusitanians, who were literate in Latin, to write Lusitanian since Lusitanian had no writing system of its own. It is difficult to determine if the letters have a different pronunciation than the Latin values but the frequent alternations of c with g (porcom vs. porgom) and t with d (ifadem vs. ifate), and the frequent loss of g between vowels, points to a lenis pronunciation compared to Latin. In particular, between vowels and after r, b may have represented the sound /β/, and correspondingly g was written for /ɣ/, and d for /ð/.

Inscriptions

RUFUS ET

TIRO SCRIP

SERUNT

VEAMINICORI

DOENTI

ANGOM

LAMATICOM

CROUCEAI

MAGA

REAICOI PETRANIOI R[?]

ADOM PORGOMIOUEA [or ...IOUEAI]

CAELOBRIGOI

Cabeço das Fráguas:[46]

OILAM TREBOPALA

INDO PORCOM LAEBO

COMAIAM ICONA LOIM

INNA OILAM USSEAM

TREBARUNE INDI TAUROM

IFADEM REUE...

Translation:[17]

A sheep [lamb?] for Trebopala

and a pig for Laebo,

[a sheep] of the same age for Iccona Loiminna,

a one year old sheep for

Trebaruna and a fertile bull...

for Reve...

Arroyo de la Luz (I & II):[47]

AMBATVS

SCRIPSI

CARLAE PRAISOM

SECIAS ERBA MVITIE

AS ARIMO PRAESO

NDO SINGEIETO

INI AVA INDI VEA

VN INDI VEDAGA

ROM TEVCAECOM

INDI NVRIM INDI

VDEVEC RVRSENCO

AMPILVA

INDI

LOEMINA INDI ENV

PETANIM INDI AR

IMOM SINTAMO

M INDI TEVCOM

SINTAMO

Arroyo de la Luz (III):[48]

ISACCID·RVETI ·

PVPPID·CARLAE·EN

ETOM·INDI·NA.[

....]CE·IOM·

M·

Ribeira da Venda:[1]

[- - - - - -] AM•OILAM•ERBAM [---]

HARASE•OILA•X•BROENEIAE•H[------]

[....]OILA•X•REVE AHARACVI•TAV[---]

IFATE•X•BANDI HARACVI AV[---]

MVNITIE CARIA CANTIBIDONE•[--

APINVS•VENDICVS•ERIACAINV[S]

OVGVI[-]ANI

ICCINVI•PANDITI•ATTEDIA•M•TR

PVMPI•CANTI•AILATIO

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 Prósper, Blanca Maria; Villar, Francisco (2009). "Nueva inscripción lusitana procedente de Portalegre". Emerita. LXXVII (1): 1–32. doi:10.3989/emerita.2009.v77.i1.304. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 Villar, Francisco (2000). Indoeuropeos y no indoeuropeos en la Hispania Prerromana (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. ISBN 84-7800-968-X. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- 1 2 Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. p. 55.

- 1 2 Stifter, David (2006). Sengoídelc (Old Irish for Beginners). Syracuse University Press. pp. 3, 7. ISBN 0-8156-3072-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Koch, John T (2011). Tartessian 2: The Inscription of Mesas do Castelinho ro and the Verbal Complex. Preliminaries to Historical Phonology. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-1-907029-07-3. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011.

- ↑ "Lusitanisch, Keltiberisch, Keltisch", Studia Palaeohispanica. Jurgen Untermann, 1987. Vitoria 1987, pp. 57-76.

- ↑ Anderson, JM. "Preroman indo-european languages of the hispanic peninsula". Revue des Études Anciennes Année 1985. 87 (3–4): 319–326..

- 1 2 Anderson, James M. (1985). "Preroman indo-european languages of the hispanic peninsula". Revue des Études Anciennes. 87 (3): 319–326. doi:10.3406/rea.1985.4212.

- ↑ https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/bitstream/10216/72404/2/28609.pdf

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A-Celti. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781851094400.

- 1 2 Wodtko, Dagmar S (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 11: The Problem of Lusitanian. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 335–367. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ↑ Ballester, X. (2004). "Hablas indoeuropeas y anindoeuropeas en la Hispania prerromana". Real Academia de Cultura Valenciana, Sección de Estudios Ibéricos. Estudios de Lenguas y Epigrafía Antiguas –ELEA. 6: 114–116.

- ↑ Anderson, J. M. 1985. «Pre-Roman Indo-European languages of the Hispanic Peninsula», Revue des Études Anciennes 87, 1985, pp. 319–326.

- ↑ Untermann, J. 1987. «Lusitanisch, Keltiberisch, Keltisch», in: J. Gorrochategui, J. L. Melena & J. Santos (eds.), Studia Palaeohispanica. Actas del IV Coloquio sobre Lenguas y Culturas Paleohispánicas (Vitoria/Gasteiz, 6–10 mayo 1985). (= Veleia 2–3, 1985–1986), Vitoria-Gasteiz ,1987, pp. 57–76.

- ↑ Pedreño, Juan Carlos Olivares (2005). "Celtic Gods of the Iberian Peninsula". E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6 (1). Archived from the original on 24 September 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- 1 2 Quintela, Marco V. García (2005). "Celtic Elements in Northwestern Spain in Pre-Roman times". E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. Center for Celtic Studies, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. 6 (1). Archived from the original on 6 January 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ↑ Koch, John T (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 9: Paradigm Shift? Interpreting Tartessian as Celtic. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. p. 293. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ↑ Zair, Nicholas. "Latin Bardus and Gurdus". Glotta 94 (2018): 311-18. doi:10.2307/26540737.

- ↑ Wodtko 2010, p.252

- ↑ Búa Carballo., D. Carlos (2014). "I". III CONGRESSO INTERNACIONAL SOBRE CULTURA CELTA "Os Celtas da Europa Atlântica". Instituto Galego de Estudos Célticos (IGEC). p. 112. ISBN 978-84-697-2178-0.

- ↑ Wodtko, Dagmar S (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 11: The Problem of Lusitanian. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 360–361. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry (2003). The Celts – A Very Short Introduction – see figure 7. Oxford University Press. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-19-280418-9.

- ↑ Ballester, X. (2004). ""Páramo" o del problema del la */p/ en celtoide". Studi Celtici. 3: 45–56.

- ↑ Asmus, Sabine; Braid, Barbara (2014). Unity in Diversity, Volume 2: Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4438-6589-0.

- ↑ Hill, E. W.; Jobling, M. A.; Bradley, D. G. (2000). "Y chromosome variation and Irish origins". Nature. 404 (6776): 351–352. Bibcode:2000Natur.404..351H. doi:10.1038/35006158. PMID 10746711. S2CID 4414538.

- ↑ McEvoy, B.; Richards, M.; Forster, P.; Bradley, D. G. (2004). "The longue durée of genetic ancestry: multiple genetic marker systems and Celtic origins on the Atlantic facade of Europe". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75 (4): 693–702. doi:10.1086/424697. PMC 1182057. PMID 15309688.

- ↑ Masheretti, S.; Rogatcheva, M. B.; Gündüz, I.; Fredga, K.; Searle, J. B. (2003). "How did pygmy shrews colonize Ireland? Clues from a phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences". Proc. R. Soc. B. 270 (1524): 1593–1599. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2406. PMC 1691416. PMID 12908980.

- ↑ Alejandro G. Sinner (ed.), Javier Velaza (ed.), Palaeohispanic Languages and Epigraphies, OUP, 2019: Chapter 11, p.304

- ↑ Markey, Thomas (2008). Shared Symbolics, Genre Diffusion, Token Perception and Late Literacy in North-Western Europe. NOWELE.

- ↑ Krzysztof Tomasz Witczak, On the Indo-European origin of two Lusitanian theonyms ("Laebo" and "Reve"), 1999, p.67

- ↑ "In the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, and more specifically between the west and north Atlantic coasts and an imaginary line running north-south and linking Oviedo and Merida, there is a corpus of Latin inscriptions with particular characteristics of its own. This corpus contains some linguistic features that are clearly Celtic and others that in our opinion are not Celtic. The former we shall group, for the moment, under the label northwestern Hispano-Celtic. The latter are the same features found in well-documented contemporary inscriptions in the region occupied by the Lusitanians, and therefore belonging to the variety known as LUSITANIAN, or more broadly as GALLO-LUSITANIAN. As we have already said, we do not consider this variety to belong to the Celtic language family." Jordán Colera 2007: p.750

- ↑ Blanca María Prósper The inscription of Cabéço das Fraguas revisited. Lusitanian and Alteuropäisch populations in the west of the Iberian Peninsula. Transactions of the Philological Society 97, 1999, 151-83,

- ↑ Blanca Maria Prósper, The Lusitanian oblique cases revisted: New light on the dative endings, 2021

- ↑ Eustaquio Sánchez Salor, Julio Esteban Ortega, Un testimonio del dios Labbo en una inscripción lusitana de Plasencia, Cáceres. ¿Labbo también en Cabeço das Fráguas?, 2021

- ↑ Prósper, BM (1999). "The inscription of Cabeço das Fráguas revisited. Lusitanian and Alteuropäisch populations in the West of the Iberian Peninsula". Transactions of the Philological Society. Wiley. 97 (2): 151–184. doi:10.1111/1467-968X.00047.

- ↑ Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. Princeton University Press. pp. 368, 380. ISBN 978-0-691-14818-2.

- ↑ Mallory, J.P. (1999). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth (reprint ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 108, 244–250. ISBN 978-0-500-27616-7.

- ↑ Anthony 2007, p. 360.

- ↑ James P. Mallory (2013). "The Indo-Europeanization of Atlantic Europe". In J. T. Koch; B. Cunliffe (eds.). Celtic From the West 2: Rethinking the Bronze Age and the Arrival of Indo–European in Atlantic Europe. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 17–40. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ↑ "The number of inscriptions written totally or partially in Lusitanian is limited: only six or seven with Lusitanian vocabulary and/or grammatical words, usually dated to the first two centuries CE. All are written in the Latin alphabet, and most are bilingual, displaying code-switching between Latin and Lusitanian. There are also many deity names in Latin inscriptions. The chapter summarizes Lusitanian phonology, morphology, and syntax, though entire categories are not attested at all. Scholarly debate about the classification of Lusitanian has focused on whether it should be considered a Celtic language. The chapter reviews the main issues, such as the fate of Indo-European */p/ or the outcome of voiced aspirate stops. The prevailing opinion is that Lusitanian was not Celtic. It must have diverged from western Indo-European dialects before the kernel of what would evolve into the Celtic and Italic families had been constituted. An appendix provides the text of extant Lusitanian inscriptions and representative Latin inscriptions displaying Lusitanian deity names and/or their epithets." E.R. Luján 2019: p.304-334

- ↑ Luján, E. R. (2019). "Language and writing among the Lusitanians". Palaeohispanic Languages and Epigraphies. Oxford University Press. p. 318. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198790822.003.0011. ISBN 978-0-19-879082-2. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ↑ Wodtko, Dagmar (2020). "Lusitanisch". Palaeohispanica. Revista sobre lenguas y culturas de la Hispania Antigua (20): 689–719. doi:10.36707/palaeohispanica.v0i20.379. ISSN 1578-5386. S2CID 241467632. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ↑ Ruiz, J. Siles. "Sobre la inscripción lusitano-latina de Visseu". In: Nuevas interpretaciones del Mundo Antiguo: papers in honor of professor José Luis Melena on the occasion of his retirement / coord. por Elena Redondo Moyano, María José García Soler, 2016. pp. 347-356. ISBN 978-84-9082-481-8

- ↑ Hübner, E. (ed.) Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum vol. II, Supplementum. Berlin: G. Reimer (1892)

- ↑ Untermann, J. Monumenta Linguarum Hispanicarum (1980–97)

- ↑ Cardim Ribeiro, José (2021). «La Inscripción Lusitana De Sansueña ("Arroyo I"»). In: Palaeohispanica. Revista Sobre Lenguas Y Culturas De La Hispania Antigua 21 (diciembre), pp. 237-99. https://doi.org/10.36707/palaeohispanica.v21i0.420.

- ↑ Villar, F. and Pedrero, R. La nueva inscripción lusitana: Arroyo de la Luz III (2001) (in Spanish)

Further reading

General studies

- Anderson, James M. (1985). "Preroman indo-european languages of the hispanic peninsula". Revue des Études Anciennes. 87 (3): 319–326. doi:10.3406/rea.1985.4212..

- Anthony, David W. (2007): The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. Princeton, NJ. pp. 360–380.

- Blažek, Václav (2006). "Lusitanian language". Sborník prací Filozofické fakulty brněnské univerzity. N, Řada klasická = Graeco-Latina Brunensia. 55 (11): 5–18. hdl:11222.digilib/114048. ISSN 1211-6335..

- Gorrochategui, Joaquín (1985–1986). "En torno a la clasificación del lusitano". Veleia: Revista de prehistoria, historia antigua, arqueología y filología clásicas. 2–3: 77–92. ISSN 0213-2095..

- Luján, Eugenio (2019). "Language and writing among the Lusitanians". Paleohispanic Languages and Epigraphies. Oxford University Press. pp. 304–334. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198790822.003.0011. ISBN 9780191833274..

- Mallory, J.P. (2016): Archaeology and language shift in Atlantic Europe, in Celtic from the West 3, eds Koch, J.T. & Cunliffe, B.. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 387–406.

- Vallejo, José M.ª (2013). "Hacia Una Definición Del Lusitano". Palaeohispanica. Revista Sobre Lenguas y Culturas de la Hispania Antigua. 13: 273–91. doi:10.36707/palaeohispanica.v0i13.165 (inactive 1 August 2023).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link). - Untermann, Jürgen (1985–1986). "Lusitanisch, Keltiberisch, Keltisch" (PDF). Veleia: Revista de prehistoria, historia antigua, arqueología y filología clásicas. 2–3: 57–76. ISSN 0213-2095.

- Wodtko, Dagmar S. (2020). "Lusitanisch". Palaeohispanica: Revista sobre lenguas y culturas de la Hispania antigua. 20 (20): 689–719. doi:10.36707/palaeohispanica.v0i20.379. ISSN 1578-5386. S2CID 241467632..

Studies on epigraphy

- Cardim Ribeiro, José (2014). "We give you this lamb, o Trebopala!": the lusitanian invocation of Cabeço das Fráguas (Portugal)". Conímbriga. 53: 99–144. doi:10.14195/1647-8657_53_4..

- Cardim Ribeiro, José (2009). "Terão certos teónimos paleohispânicos sido alvo de interpretações (pseudo-)etimológicas durante a romanidade passíveis de se reflectirem nos respectivos cultos?". Acta Paleohispanica X - Paleohispanica. 9: 247–270. ISSN 1578-5386.

- Cardim, José, y Hugo Pires (2021). «Sobre La Fijación Textual De Las Inscripciones Lusitanas De Lamas De Moledo, Cabeço Das Fráguas Y Arronches: La Contribución Del "Modelo De Residuo Morfológico" (MRM), Resultados Y Principales Consecuencias Interpretativa»s. In: Palaeohispanica. Revista Sobre Lenguas Y Culturas De La Hispania Antigua 21 (diciembre), 301-52. https://doi.org/10.36707/palaeohispanica.v21i0.416.

- Prósper, Blanca M.; Villar, Francisco (2009). "NUEVA INSCRIPCIÓN LUSITANA PROCEDENTE DE PORTALEGRE". EMERITA, Revista de Lingüística y Filología Clásica. LXXVII (1): 1–32. doi:10.3989/emerita.2009.v77.i1.304. ISSN 0013-6662..

- Prósper, Blanca Maria.The Lusitanian oblique cases revisted: New light on the dative endings. In: Curiositas nihil recusat. Studia Isabel Moreno Ferrero dicata: estudios dedicados a Isabel Moreno Ferrero. Juan Antonio González Iglesias (ed. lit.), Julián Víctor Méndez Dosuna (ed. lit.), Blanca María Prósper (ed. lit.), 2021. págs. 427-442. ISBN 978-84-1311-643-3.

- Sánchez Salor, Eustaquio; Esteban Ortega, Julio (2021). "Un testimonio del dios Labbo en una inscripción lusitana de Plasencia, Cáceres. ¿Labbo también en Cabeço das Fráguas?". Emerita, Revista de Lingüística y Filología Clásica. LXXXIX (1): 105–126. doi:10.3989/emerita.2021.05.2028. hdl:10662/18053. ISSN 0013-6662. S2CID 236256764..

- Tovar, Antonio (1966). "L'inscription du Cabeço das Fráguas et la langue des Lusitaniens". Études Celtiques. 11 (2): 237–268. doi:10.3406/ecelt.1966.2167..

- Untermann, Jürgen (1997): Monumenta Linguarum Hispanicarum. IV Die tartessischen, keltiberischen und lusitanischen Inschriften, Wiesbaden.

- Villar, Francisco (1996): Los indoeuropeos y los orígenes de Europa, Madrid.

- Villar, Francisco; Pedrero Rosa (2001): «La nueva inscripción lusitana: Arroyo de la Luz III», Religión, lengua y cultura prerromanas de Hispania, pp. 663–698.