I Modi (The Ways), also known as The Sixteen Pleasures or under the Latin title De omnibus Veneris Schematibus, is a famous erotic book of the Italian Renaissance that had engravings of sexual scenes.[1] The engravings were created in a collaboration between Giulio Romano and Marcantonio Raimondi.[3][4] They were thought to have been created around 1524 to 1527.[3]

There are now no known copies of the first two editions of "I modi" by Giulio Romano and Marcantonio Raimondi.[1]

In around 1530[2] Agostino Veneziano is thought to have created a replacement set of engravings for the engravings in I modi by Giulio and Marcantonio.[1]

Giulio Romano and Marcantonio Raimondi edition - Around 1524 - 1527

The first edition of I modi was created in a collaboration between Giulio Romano and Marcantonio Raimondi.[3]

One idea is that this collaboration occurred when Giulio Romano was doing a series of erotic paintings as a commission for Federico II Gonzaga’s new Palazzo Te in Mantua and Marcantonio Raimondi based the engravings for I modi on these paintings.[5]

The engravings were published by Marcantonio in 1524, and led to his imprisonment by Pope Clement VII and the destruction of all copies of the engravings.

Giulio Romano did not become aware of the engravings by Marcantonio until the poet Pietro Aretino came to see his paintings. These are the paintings that Marcantonio is thought to have based his engravings on and Romano was still working on these paintings when Aretino came to visit. Romano was not prosecuted since—unlike Marcantonio—his images were not intended for public consumption, and he was not in the Papal States.

Aretino then composed sixteen explicit sonnets to accompany the engravings, and secured Marcantonio's release from prison.[6]

I modi was then published a second time in 1527, now with the sonnets that have given them the traditional English title Aretino's Postures. It is thought that this is the first time erotic text and images were combined, though the papacy once more seized all the copies it could find. It is thought Marcantonio escaped prison on this second occasion, but the suppression on both occasions was comprehensive.

There are presently no remaining copies of the first or second edition of I modi.[1]The images that were in these two editions of I modi are thought to have been copied several times.[1][7]

Agostino Veneziano copy - Around 1530

It is thought that Agostino Veneziano may have created a single replacement set of engravings for the images created by Giulio and Marcantonio in I modi.[1] There is one whole image and nine fragments cut from seven engravings that are in the British Museum and it is thought that all of these images come from this replacement set of engravings by Agostino.[1] These engravings by Agostino are dated to around 1530.[2]

There is an engraving of Leda and the Swan in the British Museum that is thought to be by Agostino Veneziano and it is thought to have been created in around 1524 to 1527.[7] It is speculated that this engraving has been based on an engraving from "I modi" by Giulio and Marcantonio.[7]The engraving is the same size and format as the "I modi" engravings[7] and it is speculated that it may be based on a design by Giulio Romano.[8][7]

It is thought that as well as Agostino Veneziano there were other people who contributed to the creation of this replacement set of engravings.[1]

Copies of the Agostino Veneziano copy of "I modi"

Woodcut booklet copy - Around 1555

A possibly infringing[9] copy of I modi with crude illustrations created using woodcut relief printing was created around 1555.[1][10][11]

This woodcut booklet was bound in with some contemporary texts[1] and was discovered in the 1920s. The artist who created the woodcut prints in the booklet is unknown.[1]

It is thought that this woodcut booklet is "...several generations removed from the original engravings..."[1] of Marcantonio. It is thought that these generations of I modi copies have been based on the Agostino Veneziano edition of I modi.[1]

It has been speculated that this woodcut booklet from around 1555 may have been copied from a second woodcut copy of I modi that is speculated to have been created around 1540. [12]

It is thought the woodblocks that were used to print the woodcut booklet may have been reused multiple times.[12] The images have borders that were frequently broken indicating wear and breakage in the woodblocks.[12]

One of the leaves is missing from this woodcut booklet[2] and there were I modi related images on these leaf.[1]

This woodcut booklet shows that there were more images in Giulio and Marcantonio's edition of "I modi" than is shown by the nine remaining fragments and the one whole image that are thought to be by Agostino Veneziano.[1]

It has been described that for this woodcut booklet there are two images "...in the abbreviated final signature...[that] seem to come from different traditions."[1] For one of these two images it has been commented that "...both image and text differ markedly in style from those that precede them..." in the woodcut booklet.[13]

When the images in the woodcut booklet are compared to the engravings thought to be by Agostino it is thought they have been changed to suit the woodcut medium with the images being square and reduced in size.[2]

Engraving in the Albertina Museum - 16th century

There is one engraving in the Albertina museum[14][1] that is thought to have been copied from Agostino Veneziano's edition of "I modi".[1] It matches an oval fragment in the British museum[1] and the 11th image in the woodcut booklet.

It is thought that this single engraving comes from a set of engravings[1] and only this one engraving presently remains from this set.[1]

It is dated to the 16th century and the artist is unknown.[14] It is numbered in the bottom right corner with two.[1]

Francesco Xanto Avelli Maiolica dish

It is thought that between 1531 and 1535 Francesco Xanto Avelli saw Agostino Veneziano's copy of I modi.[1] Xanto painted a maiolica dish titled The Tiber in Flood and the figures on this dish have the same postures as those in four of the images in the woodcut booklet.[1]

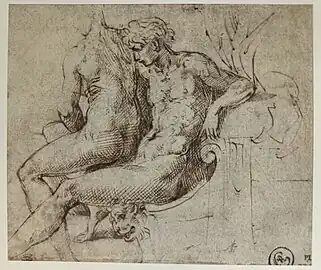

Parmigianino drawing

Parmigianino drew a copy of one of the engravings in the "I modi" with sex occurring between two figures who are seated. This drawing is similar to the 10th image in the woodcut booklet.[7] It includes similar postures of the figures and details of drapery and furniture.[7]

Engraving in the National Library of Spain

An engraving in the National Library of Spain copies one scene from the "I modi".[15] The engraving shows two figures seated having sex with a wooden cradle lying on the ground next to them and the foot of one of the figures is rocking the cradle.[15]

This image of two people seated having sex is by an unknown artist and dated to after 1530.[15]

Henry Wellesley engravings

Henry Wellesley owned two engravings that they are now in the collection of the National Library of France[1] and both engravings are related to I modi images.[1] One engraving was similar to the whole single image in the British Museum and was numbered and the other engraving was similar to the image in the Albertina Museum and was numbered two.[1]

Delaborde and Bartsch descriptions

Henri Delaborde and Adam Bartsch gave descriptions of images as belonging to the "I modi".[1] The descriptions that they gave do not relate to any existing images and perhaps are examples of additional images that may have been in the original "I modi".[1]

Images with similarities to I modi

The image in the woodcut booklet numbered 16 has similarities to two drawings that are in the Fosombrone scketchbook.[16] The figures in these drawings have a similar position to the figures that are in the woodcut booklet.[16] Differences include differences between the figures and the furniture.[16]

17th century printing

In the 17th century Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford, engaged in the surreptitious printing at the University Press of Aretino's Postures, Aretino's De omnis Veneris schematibus and the indecent engravings after Giulio and Marcantonio. The Dean, Dr. John Fell, impounded the copper plates and threatened those involved with expulsion.[17] The text of Aretino's sonnets, however, survives.

Images from I modi copies

Image 1 woodcut booklet

Image 1 woodcut booklet The corresponding image by Agostino Veneziano.

The corresponding image by Agostino Veneziano.

_02._-_Extracted_image.jpg.webp) Image 2 woodcut booklet

Image 2 woodcut booklet.jpg.webp) Corresponding fragment to image 2 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano

Corresponding fragment to image 2 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano

_03._-_Extracted_image.jpg.webp) Image 3 woodcut booklet

Image 3 woodcut booklet

Image 4 woodcut booklet

Image 4 woodcut booklet.jpg.webp) Corresponding fragment to image 4 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano . Two fragments cut from the one engraving.

Corresponding fragment to image 4 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano . Two fragments cut from the one engraving..jpg.webp) Corresponding fragment to image 4 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano

Corresponding fragment to image 4 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano

Image 7 woodcut booklet

Image 7 woodcut booklet.jpg.webp) Corresponding fragment to image 7 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano

Corresponding fragment to image 7 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano

Image 8 woodcut booklet

Image 8 woodcut booklet

Image 9 woodcut booklet

Image 9 woodcut booklet.jpg.webp) Corresponding fragment to image 9 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano

Corresponding fragment to image 9 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano This image is made from two images. One is the image from the woodcut booklet. The second is the engraving thought to be by Agostino Veneziano.[7]

This image is made from two images. One is the image from the woodcut booklet. The second is the engraving thought to be by Agostino Veneziano.[7]

Image 10 woodcut booklet

Image 10 woodcut booklet.jpg.webp) Corresponding fragment to image 10 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano

Corresponding fragment to image 10 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano

Image 11 woodcut booklet

Image 11 woodcut booklet.jpg.webp) Corresponding fragment to image 11 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano

Corresponding fragment to image 11 thought to be by Agostino Veneziano.jpg.webp) Anonymous engraving, Albertina Museum, 16th century

Anonymous engraving, Albertina Museum, 16th century This image has been made from two engravings. The first engraving is from the Albertina museum and the second is thought to be by Agostino Veneziano.[7]

This image has been made from two engravings. The first engraving is from the Albertina museum and the second is thought to be by Agostino Veneziano.[7]

Image 12 woodcut booklet

Image 12 woodcut booklet Image 13 woodcut booklet

Image 13 woodcut booklet Image 14 woodcut booklet

Image 14 woodcut booklet

![Image 15 woodcut booklet. It has been described that for this woodcut booklet there are two images "...in the abbreviated final signature...[that] seem to come from different traditions." For the image with the standing figure it has been commented that "...both image and text differ markedly in style from those that precede them" in the woodcut booklet.](../I/Posture_15_-_Woodblock_cut_copy_-_after_Marcantonio_Raimondi_-_around_1550_-_Final_two_images_-_3.jpg.webp) Image 15 woodcut booklet. It has been described that for this woodcut booklet there are two images "...in the abbreviated final signature...[that] seem to come from different traditions."[1] For the image with the standing figure it has been commented that "...both image and text differ markedly in style from those that precede them" in the woodcut booklet.[13]

Image 15 woodcut booklet. It has been described that for this woodcut booklet there are two images "...in the abbreviated final signature...[that] seem to come from different traditions."[1] For the image with the standing figure it has been commented that "...both image and text differ markedly in style from those that precede them" in the woodcut booklet.[13] Image 16 woodcut booklet. In the Fossombrone sketchbook there are drawings of two scenes that have a similar position to this image from the woodcut booklet.[16]

Image 16 woodcut booklet. In the Fossombrone sketchbook there are drawings of two scenes that have a similar position to this image from the woodcut booklet.[16]

.jpg.webp) Two fragments cut from the one engraving. These fragments not present in the woodcut booklet. Both fragments are thought to be by Agostino Veneziano.

Two fragments cut from the one engraving. These fragments not present in the woodcut booklet. Both fragments are thought to be by Agostino Veneziano..jpg.webp)

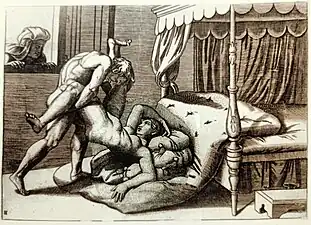

Engravings of sexual positions for a reprint of Aretino's poems

A new series of graphic and explicit engravings of sexual positions was produced by Camillo Procaccini[18] or more likely by Agostino Carracci for a later reprint of Aretino's poems.[19]

Erotic frescos of Annibale Carracci

Annibale Carracci also completed the elaborate fresco the Loves of the Gods for the Palazzo Farnese in Rome (where the Farnese Hercules which influenced both him and Agostino Carraci was housed). These images were drawn from Ovid's Metamorphoses and include nudes, but (in contrast to the sexual engravings) are not explicit, intimating rather than directly depicting the act of lovemaking.

Augustine Carracci's The Aretin or Collection of Erotic Postures - Jacques Joseph Coiny

In 1798 in Paris a collection of engravings of sexual scenes were published under the title Augustine Carracci's The Aretin or Collection of Erotic Postures.[20][21][22] The engravings were created by Jacques Joseph Coiny.

One theory is that these images were basd on the erotic poses in 'The Loves of the Gods' which was created at the start of the 17th century in Antwerp by Pieter de Jode I with the use of burin. [23] It presently remains uncertain what images these engravings were based on. It is thought that Coiny had a set of six anonymous prints and it is difficult to say which prints these were.[24]

Classical guise in Augustine Carracci's The Aretin or Collection of Erotic Postures

Several factors were used to cloak these engravings from Augustine Carracci's The Aretin or Collection of Erotic Postures in classical scholarly respectability:

- The images nominally depicted famous pairings of lovers (e.g. Antony and Cleopatra) or husband-and-wife deities (e.g. Jupiter and Juno) from classical history and mythology engaged in sexual activity, and were entitled as such. Related to this were:

- Portraying them with their usual attributes, such as:

- Cleopatra's banquets, bottom left

- Achilles's shield and helmet, bottom left

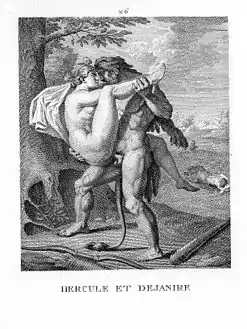

- Hercules in his lion-skin and club

- Mars with his cuirass

- Paris as a shepherd

- Bacchus with his vine-leaf crown and (bottom right) grapes

- Referring to the best known myths or historical events in which they appeared e.g.:

- Mars and Venus under the net which her husband Vulcan has designed to catch them

- 'Aeneas' and 'Dido' in the cave in which their sexual intercourse is alluded in Aeneid, Book 4

- Theseus abandoning Ariadne on Naxos, where Bacchus finds and marries her.[25]

- the wide adultery of Julia

- Messalina's participation in prostitution, as criticised in Juvenal's Satire VI.

- Referring to other Renaissance and classical tropes in the depiction of these people and deities, such as

- Portraying them with their usual attributes, such as:

- the frontispiece image is entitled Venus Genetrix,[28] and the goddess is nude and drawn in a chariot by doves, as in the classical sources.

- the bodies of those depicted show clear influences from classical statuary known at the time, such as:

- the over-muscled torsos and backs of the men[29](drawn from sculptures such as the Laocoön and his Sons, Belvedere Torso, and Farnese Hercules).[30]

- the women's clearly defined though small breasts (drawn from examples such as the Venus de' Medici and Aphrodite of Cnidus)[31]

- the elaborate hairstyles of some of the women, such as his Venus, Juno or Cleopatra (derived from Roman Imperial era busts such as this one).

- Portraying the action in a classical 'stage set' such as an ancient Greek sanctuary or temple.

- The large erect penis on the statue of Priapus or Pan atop a puteal in 'The Cult of Priapus' is derived from examples in classical sculpture and painting (like this fresco) which were beginning to be found archaeologically at this time.[32]

Differences from antique art

Augustine Carracci's The Aretin or Collection of Erotic Postures has various points of deviation from classical literature, erotica, mythology and art which suggest its classical learning is lightly worn, and make clear its actual modern setting:

- The male sexual partners' large penises (though not Priapus's) are the artist's invention rather than a classical borrowing – the idealised penis in classical art was small, not large (large penises were seen as comic or fertility symbols, as for example on Priapus, as discussed above).

- The title 'Polyenus and Chryseis' pairs the fictional Polyenus with the actual mythological character Chryseis.

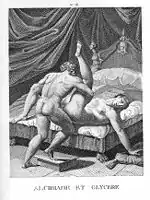

- The title 'Alcibiades and Glycera' pairs two historical figures from different periods – the 5th century BC Alcibiades and the 4th century BC Glycera

- Female satyrs did not occur in classical mythology, yet they appear twice in this work (in 'The Satyr and his wife' and 'The Cult of Priapus').[33]

- All the women and goddesses in this work (but most clearly its Venus Genetrix) have a hairless groin (like classical statuary of nude females) but also a clearly apparent vulva (unlike classical statuary).[34]

- The modern furniture, e.g.

- The various stools and cushions used to support the participants or otherwise raise them into the right positions (e.g. here)

- The other sex aids (e.g. a whip, bottom right)

- The 16th-century beds, with ornate curtains, carvings, tasselled cushions, bedposts, etc.

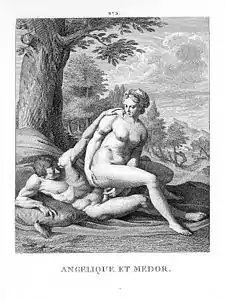

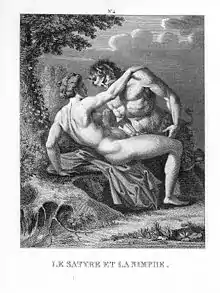

Engravings from Augustine Carracci's The Aretin or Collection of Erotic Postures

The images in the table below are the engravings from Augustine Carracci's The Aretin or Collection of Erotic Postures.[20]

These engravings have inspired the creation of erotic art from other artists including Paul Avril.[35]

| Image | No. | Title (English translation) | Male partner | Female partner | Sexual position | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 | Venus Genetrix | - | Venus Genetrix | Female figure study of nude in frontal disposition | - |

|

2 | Paris and Oenone | Paris | Oenone | Side-by-side, man on top | |

|

3 | Angelique and Medor | Medor | Angelique | Reverse cowgirl | Characters from Roland |

|

4 | The satyr and the nymph | Satyr | Nymph | Missionary position (man on top and standing, woman lying) | |

|

5 | Julia with an athlete | An athlete | Julia the Elder | Reverse cowgirl (woman standing) | Woman guiding in penis |

|

6 | Hercules and Deianaira | Hercules | Deianira | Standing missionary (woman supported by man) | |

|

7 | Mars and Venus | Mars | Venus | Missionary (woman on top[36]) | |

|

8 | The Cult of Priapus | Pan, or a male satyr | A female satyr | Missionary (male standing, woman sitting) | Statue of Priapus with characteristically disproportionate erection |

|

9 | Antony and Cleopatra | Mark Antony | Cleopatra | Side-by-side missionary | Woman guiding in penis |

|

10 | Bacchus and Ariadne | Bacchus | Ariadne | Leapfrog - woman entirely supported | Woman's legs up not kneeling as usual in this position |

|

11 | Polyenos and Chriseis | Polyenos (fictional) | Chryseis | Missionary (man on top and standing, woman lying) | |

|

12 | A satyr and his wife | Male satyr | Female satyr | Missionary (man standing, woman sitting) | |

|

13 | Jupiter and Juno | Jupiter | Juno | Standing (man standing/kneeling, woman supported [37]) | |

|

14 | Messalina in the booth of 'Lisica' | Brothel client | Messalina | Missionary (female lying, male standing) | |

|

15 | Achilles and Briseis | Achilles | Briseis | Standing (man entirely supporting woman) | |

|

16 | Ovid and Corinna | Ovid | Corinna | Missionary (man on top, woman guiding erect penis into her vagina) | Woman deepening penetration by having her legs outside his. |

|

17 | Aeneas and Dido [accompanied by a Cupid] | Aeneas | Dido | Fingering with left hand index finger (thus little nudity relative to other images) | Lesser nudity, though wet T-shirt effect round breasts; Cupid is erect |

|

18 | Alcibiades and Glycera | Alcibiades | Glycera | Missionary (man on top and standing, woman lying and legs up) | Man also raised up to right level for vagina by right foot on step |

|

19 | Pandora | ?Epimetheus (crowned figure) | Pandora | Side by side | The boy with the candle may be a classical reference.[38] |

Cultural References

The Restoration closet drama Farce of Sodom is set in "an antechamber hung with Aretine's postures. In the 1989 novel, The Sixteen Pleasures by Robert Hellenga, a copy of the book is discovered in a convent following the 1966 flood of the Arno.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 James Grantham Turner (December 2004). "Marcantonio's Lost Modi and their Copies". Print Quarterly. 21 (4): 363–364, 366, 369, 373, 375, 379, 382–384. JSTOR 41826241. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 James Grantham Turner (June 2009). "Woodcut Copics of the "Modi"". Print Quarterly. 26 (2): 115, 116–117. JSTOR 43826068. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- 1 2 3 James Grantham Turner (June 2009). "Woodcut Copics of the "Modi"". Print Quarterly. 26 (2): 117. JSTOR 43826068. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ↑ Walter Kendrick, The Secret Museum, Pornography in Modern Culture (1987:59)

- ↑ I Modi: the sixteen pleasures. An erotic album of the Italian renaissance / Giulio Romano … [et al.] edited, translated from the Italian and with a commentary by Lynne Lawner. Northwestern University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-7206-0724-8

- ↑ Sample quote: “both in your pussy and your behind, my cock will make me happy, and you happy and blissful”

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 James Grantham Turner (2017). Eros Visible: Art, Sexuality and Antiquity in Renaissance Italy. Yale University Press. pp. 37, 38, 39, 155, 156, 309, 357–358, 367, 377–378. ISBN 978-0-300-21995-1.

- ↑ James Grantham Turner (September 2007). "Notes". Print Quarterly. 24 (3): 279. JSTOR 43826068. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ↑ A History of Erotic Literature, P.J. Kearney, Macmillan 1982.

- ↑ "I MODI : 1550 WOODBLOCK EDITION". eroti-cart.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ↑ Formerly owned by the son of Toscanini, now in a private collection. See the article "Marcantonio's Lost Modi and their Copies" by James Grantham Turner, Print Quarterly. December 2004

- 1 2 3 James Grantham Turner (June 2009). "Woodcut Copics of the "Modi"". Print Quarterly. 26 (2): 116–117. JSTOR 43826068. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- 1 2 James Grantham Turner (Spring 2009). "STANDING BRONZES, RICCIO, AND "I MODI"". Source: Notes in the History of Art. 28 (3): 8. JSTOR 43826068. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- 1 2 "A couple making love". Albertina. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 James Grantham Turner (2017). Eros Visible: Art, Sexuality and Antiquity in Renaissance Italy. Yale University Press. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-0-300-21995-1.

- 1 2 3 4 James Grantham Turner (June 2009). "Woodcut Copics of the "Modi"". Print Quarterly. 26 (2): 121–122. JSTOR 43826068. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ↑ R. W. Ketton-Cremer, "Humphrey Prideaux", Norfolk Assembly (London: Faber & Faber) 1957:65.

- ↑ Francis Haskell, Taste and the Antique, (ISBN 0-300-02641-2).

- ↑ IRONIE, article on Carracci’s engravings (in French)

- 1 2 The frontispiece states À la nouvelle Cythère, without a date or place of publication.

- ↑ Venus Erotic Art Museum

- ↑ Erotica in Art — Agostino Carracci in the “History of Art” Archived 2006-11-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ (in French) Louis Dunand and Philippe Lemarchand, Augustin Carrache. Les amours des Dieux, Genève, Slatkine, 1990, pp. 1009–1033.

- ↑ (in French) Nathalie Strasser in Éros invaincu. La Bibliothèque Gérard Nordmann, Genève, Cercle d'art, 2004, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Theseus's departing ship is visible on the horizon, top right.

- ↑ This trope did not fully exist in classical art - in frescoes and polychromatic sculptures, Venus was always fair-skinned, but her hair colour could vary from brown through to blond – but became fixed due to medieval and Renaissance art (e.g. Botticelli's Venus and Mars).

- ↑ A trope copied from classical and Renaissance sources.

- ↑ An attested epithet of the love/lust goddess Venus, although under that name she was more a mother goddess than a love/lust goddess.

- ↑ Also, in one or two cases, the women's, though this has far less, if any, precedent in classical sculpture.

- ↑ See also the modern phenomenon of the beefcake in erotic art.

- ↑ Though their thighs are often larger than in the examples from classical statuary.

- ↑ On the other hand, the posture in the engraving is not to be found in any known examples and is probably Caracci's own invention. Certainly archaeological examples usually (though not always) tend to show Priapus's erect and oversized penis hanging down, not standing up parallel with his chest as here, and give less importance to large or oversized testicles than in this engraving.

- ↑ Male satyrs having sex with nymphs, on the other hand, did appear in Greek myth – as has been taken up in Renaissance art – , though this was more frequently rape in the myths rather than the apparent consensual sex in the engraving.

- ↑ The men's pubic hair in the engravings does not pose a problem, since pubic hair was depicted on ancient nudes.

- ↑ "Paul Avril". arterotisme.com. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ↑ Though lying not sitting, and with left foot supported by stool

- ↑ Or, more precisely, woman partly lying, partly supported by bed, and partly supported on left arm.

- ↑ To the classical "'Puer sufflans ignes" in Pliny. Also, the satyr who has attempted to join the lovemakers (but been kicked in the groin by the male) has an erection as a result of his voyeurism.

Notes

Talvacchia, Bette "Taking Positions: On the Erotic in Renaissance Culture" Princeton University Press 1999 Page: 250 ISBN 978-0691026329

External links

![]() Media related to I modi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to I modi at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg.webp)