| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Amino-1-methyl-5H-imidazol-4-one | |

| Other names

2-Amino-1-methylimidazol-4-ol | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| 3DMet | |

| 112061 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.424 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Creatinine |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1789 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H7N3O | |

| Molar mass | 113.120 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White crystals |

| Density | 1.09 g cm−3 |

| Melting point | 300 °C (572 °F; 573 K)[1] (decomposes) |

| 1 part per 12[1]

90 mg/mL at 20°C[2] | |

| log P | -1.76 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 12.309 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 1.688 |

| Isoelectric point | 11.19 |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C) |

138.1 J K−1 mol−1 (at 23.4 °C) |

Std molar entropy (S⦵298) |

167.4 J K−1 mol−1 |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−240.81–239.05 kJ mol−1 |

Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−2.33539–2.33367 MJ mol−1 |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 290 °C (554 °F; 563 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Creatinine (/kriˈætɪnɪn, -niːn/; from Ancient Greek: κρέας (kréas) 'flesh') is a breakdown product of creatine phosphate from muscle and protein metabolism. It is released at a constant rate by the body (depending on muscle mass).[3][4]

Biological relevance

Serum creatinine (a blood measurement) is an important indicator of kidney health, because it is an easily measured byproduct of muscle metabolism that is excreted unchanged by the kidneys. Creatinine itself is produced[5] via a biological system involving creatine, phosphocreatine (also known as creatine phosphate), and adenosine triphosphate (ATP, the body's immediate energy supply).

Creatine is synthesized primarily in the liver from the methylation of glycocyamine (guanidino acetate, synthesized in the kidney from the amino acids arginine and glycine) by S-adenosyl methionine. It is then transported through blood to the other organs, muscle, and brain, where, through phosphorylation, it becomes the high-energy compound phosphocreatine.[6] Creatine conversion to phosphocreatine is catalyzed by creatine kinase; spontaneous formation of creatinine occurs during the reaction.[7]

Creatinine is removed from the blood chiefly by the kidneys, primarily by glomerular filtration, but also by proximal tubular secretion. Little or no tubular reabsorption of creatinine occurs. If the filtration in the kidney is deficient, blood creatinine concentrations rise. Therefore, creatinine concentrations in blood and urine may be used to calculate the creatinine clearance (CrCl), which correlates approximately with the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Blood creatinine concentrations may also be used alone to calculate the estimated GFR (eGFR).

The GFR is clinically important as a measurement of kidney function. In cases of severe kidney dysfunction, though, the CrCl rate will overestimate the GFR because hypersecretion of creatinine by the proximal tubules will account for a larger fraction of the total creatinine cleared.[8] Ketoacids, cimetidine, and trimethoprim reduce creatinine tubular secretion and, therefore, increase the accuracy of the GFR estimate, in particular in severe kidney dysfunction. (In the absence of secretion, creatinine behaves like inulin).

An alternative estimation of kidney function can be made when interpreting the blood plasma concentration of creatinine along with that of urea. BUN-to-creatinine ratio (the ratio of blood urea nitrogen to creatinine) can indicate other problems besides those intrinsic to the kidney; for example, a urea concentration raised out of proportion to the creatinine may indicate a prerenal problem such as volume depletion.

Counterintuitively, supporting the observation of higher creatinine production in women compared to men, and putting into question the algorithms for GFR that do not distinguish for sex accordingly, women have higher muscle protein synthesis and higher muscle protein turnover across the life span.[9] As HDL supports muscle anabolism, higher muscle protein turnover links increased creatine to the generally higher serum HDL in women as compared to serum HDL in men and the HDL associated benefits like reduced incidence of cardiovascular complications and reduced COVID-19 severity.[10][11][12]

Antibacterial and potential immunosuppressive properties

Studies indicate creatinine can be effective at killing bacteria of many species in both the Gram positive and Gram negative as well as diverse antibiotic resistant bacterial strains.[13] Creatinine appears not to affect growth of fungi and yeast; this can be used to isolate slower growing fungi free from the normal bacterial populations found in most environmental samples. The mechanism by which creatinine kills bacteria is not presently known. A recent report also suggests that creatinine may have immunosuppressive properties.[14][15]

Diagnostic use

Serum creatinine is the most commonly used indicator (but not direct measure) of renal function. Elevated creatinine is not always representative of a true reduction in GFR. A high reading may be due to increased production of creatinine not due to decreased kidney function, to interference with the assay, or to decreased tubular secretion of creatinine. An increase in serum creatinine can be due to increased ingestion of cooked meat (which contains creatinine converted from creatine by the heat from cooking) or excessive intake of protein and creatine supplements, taken to enhance athletic performance. Intense exercise can increase creatinine by increasing muscle breakdown. Dehydration secondary to an inflammatory process with fever may cause a false increase in creatinine concentrations not related to an actual kidney injury, as in some cases with cholecystitis. Several medications and chromogens can interfere with the assay. Creatinine secretion by the tubules can be blocked by some medications, again increasing measured creatinine.[16]

Serum creatinine

Diagnostic serum creatinine studies are used to determine renal function.[4] The reference interval is 0.6–1.3 mg/dL (53–115 μmol/L).[4] Measuring serum creatinine is a simple test, and it is the most commonly used indicator of renal function.[6]

A rise in blood creatinine concentration is a late marker, observed only with marked damage to functioning nephrons. Therefore, this test is unsuitable for detecting early-stage kidney disease. A better estimation of kidney function is given by calculating the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). eGFR can be accurately calculated without a 24-hour urine collection using serum creatinine concentration and some or all of the following variables: sex, age, weight, and (no longer https://www.kidney.org/content/laboratory-implementation-nkf-asn-task-force-reassessing-inclusion-race-diagnosing-kidney) race, as suggested by the American Diabetes Association.[17] Many laboratories will automatically calculate eGFR when a creatinine test is requested. Algorithms to estimate GFR from creatinine concentration and other parameters are discussed in the renal function article.

A concern as of late 2010 relates to the adoption of a new analytical methodology, and a possible impact this may have in clinical medicine. Most clinical laboratories now align their creatinine measurements against a new standardized isotope dilution mass spectrometry (IDMS) method to measure serum creatinine. IDMS appears to give lower values than older methods when the serum creatinine values are relatively low, for example 0.7 mg/dL. The IDMS method would result in a comparative overestimation of the corresponding calculated GFR in some patients with normal renal function. A few medicines are dosed even in normal renal function on that derived GFR. The dose, unless further modified, could now be higher than desired, potentially causing increased drug-related toxicity. To counter the effect of changing to IDMS, new FDA guidelines have suggested limiting doses to specified maxima with carboplatin, a chemotherapy drug.[18]

A 2009 Japanese study found a lower serum creatinine concentration to be associated with an increased risk for the development of type 2 diabetes in Japanese men.[19]

Urine creatinine

Males produce approximately 150 μmol to 200 μmol of creatinine per kilogram of body weight per 24 h while females produce approximately 100 μmol/kg/24 h to 150 μmol/kg/24 h. In normal circumstances, all this daily creatinine production is excreted in the urine.

Creatinine concentration is checked during standard urine drug tests. An expected creatinine concentration indicates the test sample is undiluted, whereas low amounts of creatinine in the urine indicate either a manipulated test or low initial baseline creatinine concentrations. Test samples considered manipulated due to low creatinine are not tested, and the test is sometimes considered failed.

Interpretation

In the United States and in most European countries creatinine is usually reported in mg/dL, whereas in Canada, Australia,[20] and a few European countries, μmol/L is the usual unit. One mg/dL of creatinine is 88.4 μmol/L.

The typical human reference ranges for serum creatinine are 0.5 mg/dL to 1.0 mg/dL (about 45 μmol/L to 90 μmol/L) for women and 0.7 mg/dL to 1.2 mg/dL (60 μmol/L to 110 μmol/L) for men. The significance of a single creatinine value must be interpreted in light of the patient's muscle mass. Patients with greater muscle mass have higher creatinine concentrations.

The trend of serum creatinine concentrations over time is more important than absolute creatinine concentration.

Serum creatinine concentrations may increase when an ACE inhibitor (ACEI) is taken for heart failure and chronic kidney disease. ACE inhibitors provide survival benefits for patients with heart failure and slow the disease progression in patients with chronic kidney disease. An increase not exceeding 30% is to be expected with ACEI use. Therefore, usage of ACEI should not be stopped unless an increase of serum creatinine exceeded 30% or hyperkalemia develops.[21]

Chemistry

In chemical terms, creatinine is a lactam and an imidazolidinone, so a spontaneously formed cyclic derivative of creatine.[22]

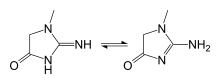

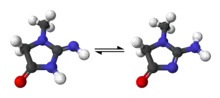

Several tautomers of creatinine exist; ordered by contribution, they are:

- 2-Amino-1-methyl-1H-imidazol-4-ol (or 2-amino-1-methylimidazol-4-ol)

- 2-Amino-1-methyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-4-one

- 2-Imino-1-methyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-imidazol-4-ol (or 2-imino-1-methyl-3H-imidazol-4-ol)

- 2-Imino-1-methylimidazolidin-4-one

- 2-Imino-1-methyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-4-ol (or 2-imino-1-methyl-5H-imidazol-4-ol)

Creatinine starts to decompose around 300 °C.

See also

- Cystatin C, novel marker of kidney function

- Jaffe reaction, an example of creatinine assay methodology

- Rhabdomyolysis, may be diagnosed using creatinine levels

- Nephrotic syndrome

References

- 1 2 Merck Index, 11th Edition, 2571

- ↑ "Creatinine, anhydrous - CAS 60-27-5". Scbt.com. Archived from the original on 2016-10-22. Retrieved 2016-10-21.

- ↑ "Creatinine tests - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Archived from the original on 2022-06-05.

- 1 2 3 Lewis SL, Bucher L, Heitkemper MM, Harding MM, Kwong J, Roberts D (September 2016). Medical-surgical nursing : assessment and management of clinical problems (10th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1025. ISBN 978-0-323-37143-8. OCLC 228373703.

- ↑ "What Is a Creatinine Blood Test? Low & High Ranges". Medicinenet.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- 1 2 Taylor EH (1989). Clinical Chemistry. Wiley. pp. 4, 58–62. ISBN 0-471-85342-9. OCLC 19065010.

- ↑ Allen PJ (May 2012). "Creatine metabolism and psychiatric disorders: Does creatine supplementation have therapeutic value?". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 36 (5): 1442–62. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.03.005. PMC 3340488. PMID 22465051.

- ↑ Shemesh O, Golbetz H, Kriss JP, Myers BD (November 1985). "Limitations of creatinine as a filtration marker in glomerulopathic patients". Kidney International. 28 (5): 830–8. doi:10.1038/ki.1985.205. PMID 2418254.

- ↑ Henderson GC, Dhatariya K, Ford GC, Klaus KA, Basu R, Rizza RA, et al. (February 2009). "Higher muscle protein synthesis in women than men across the lifespan, and failure of androgen administration to amend age-related decrements". FASEB Journal. 23 (2): 631–41. doi:10.1096/fj.08-117200. PMC 2630787. PMID 18827019.

- ↑ Lewis GF, Rader DJ (June 2005). "New insights into the regulation of HDL metabolism and reverse cholesterol transport". Circulation Research. 96 (12): 1221–32. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000170946.56981.5c. PMID 15976321. S2CID 2050414.

- ↑ Lehti M, Donelan E, Abplanalp W, Al-Massadi O, Habegger KM, Weber J, et al. (November 2013). "High-density lipoprotein maintains skeletal muscle function by modulating cellular respiration in mice". Circulation. 128 (22): 2364–71. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001551. PMC 3957345. PMID 24170386.

- ↑ Masana L, Correig E, Ibarretxe D, Anoro E, Arroyo JA, Jericó C, et al. (March 2021). "Low HDL and high triglycerides predict COVID-19 severity". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 7217. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.7217M. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-86747-5. PMC 8010012. PMID 33785815.

- ↑ McDonald T, Drescher KM, Weber A, Tracy S (March 2012). "Creatinine inhibits bacterial replication". The Journal of Antibiotics. 65 (3): 153–156. doi:10.1038/ja.2011.131. PMID 22293916.

- ↑ Smithee S, Tracy S, Drescher KM, Pitz LA, McDonald T (October 2014). "A novel, broadly applicable approach to isolation of fungi in diverse growth media". Journal of Microbiological Methods. 105: 155–61. doi:10.1016/j.mimet.2014.07.023. PMID 25093757.

- ↑ Leland KM, McDonald TL, Drescher KM (September 2011). "Effect of creatine, creatinine, and creatine ethyl ester on TLR expression in macrophages". International Immunopharmacology. 11 (9): 1341–7. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2011.04.018. PMC 3157573. PMID 21575742.

- ↑ Samra M, Abcar AC (2012). "False estimates of elevated creatinine". The Permanente Journal. 16 (2): 51–2. doi:10.7812/tpp/11-121. PMC 3383162. PMID 22745616.

- ↑ Gross JL, de Azevedo MJ, Silveiro SP, Canani LH, Caramori ML, Zelmanovitz T (January 2005). "Diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment". Diabetes Care. 28 (1): 164–76. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.1.164. PMID 15616252.

- ↑ "Carboplatin dosing". Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 2011-11-19.

- ↑ Harita N, Hayashi T, Sato KK, Nakamura Y, Yoneda T, Endo G, Kambe H (March 2009). "Lower serum creatinine is a new risk factor of type 2 diabetes: the Kansai healthcare study". Diabetes Care. 32 (3): 424–6. doi:10.2337/dc08-1265. PMC 2646021. PMID 19074997.

- ↑ Faull R (2007). "Prescribing in renal disease". Australian Prescriber. 30 (1): 17–20. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2007.008.

- ↑ Ahmed A (July 2002). "Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with heart failure and renal insufficiency: how concerned should we be by the rise in serum creatinine?". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 50 (7): 1297–300. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50321.x. PMID 12133029. S2CID 31459410.

- ↑ "Creatinine". Archived from the original on 2022-04-09. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

External links

- Marshall W (2012). "Creatinine: analyte monograph" (PDF). The Association for Clinical Biochemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2020.