Iterative and incremental development is any combination of both iterative design or iterative method and incremental build model for development.

Usage of the term began in software development, with a long-standing combination of the two terms iterative and incremental[1] having been widely suggested for large development efforts. For example, the 1985 DOD-STD-2167[2] mentions (in section 4.1.2): "During software development, more than one iteration of the software development cycle may be in progress at the same time." and "This process may be described as an 'evolutionary acquisition' or 'incremental build' approach." In software, the relationship between iterations and increments is determined by the overall software development process.

| Part of a series on |

| Software development |

|---|

Overview

The basic idea behind this method is to develop a system through repeated cycles (iterative) and in smaller portions at a time (incremental), allowing software developers to take advantage of what was learned during development of earlier parts or versions of the system. Learning comes from both the development and use of the system, where possible key steps in the process start with a simple implementation of a subset of the software requirements and iteratively enhance the evolving versions until the full system is implemented. At each iteration, design modifications are made and new functional capabilities are added.[3]

The procedure itself consists of the initialization step, the iteration step, and the Project Control List. The initialization step creates a base version of the system. The goal for this initial implementation is to create a product to which the user can react. It should offer a sampling of the key aspects of the problem and provide a solution that is simple enough to understand and implement easily. To guide the iteration process, a project control list is created that contains a record of all tasks that need to be performed. It includes items such as new features to be implemented and areas of redesign of the existing solution. The control list is constantly being revised as a result of the analysis phase.

An iteration involves redesign and implementation, which is meant to be simple, straightforward, and modular, supporting redesign at that stage or as a future task added to the project control list. The level of design detail is not dictated by the iterative approach. In a light-weight iterative project the code may represent the major source of documentation of the system; however, in a critical iterative project a formal Software Design Document may be used. The analysis of an iteration is based upon user feedback and the program analysis facilities available. It involves analysis of the structure, modularity, usability, reliability, efficiency, and achievement of goals. The project control list is modified in light of the analysis results.

Phases

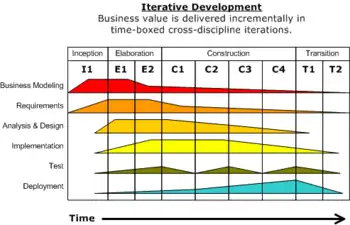

Incremental development slices the system functionality into increments (portions). In each increment, a slice of functionality is delivered through cross-discipline work, from the requirements to the deployment. The Unified Process groups increments/iterations into phases: inception, elaboration, construction, and transition.

- Inception identifies project scope, requirements (functional and non-functional) and risks at a high level but in enough detail that work can be estimated.

- Elaboration delivers a working architecture that mitigates the top risks and fulfills the non-functional requirements.

- Construction incrementally fills-in the architecture with production-ready code produced from analysis, design, implementation, and testing of the functional requirements.

- Transition delivers the system into the production operating environment.

Each of the phases may be divided into 1 or more iterations, which are usually time-boxed rather than feature-boxed. Architects and analysts work one iteration ahead of developers and testers to keep their work-product backlog full.

Usage/History

Many examples of early usage are provided in Craig Larman and Victor Basili's article "Iterative and Incremental Development: A Brief History",[4] with one of the earliest being NASA's 1960s Project Mercury.

Some of those Mercury engineers later formed a new division within IBM, where "another early and striking example of a major IID success [was] the very heart of NASA’s space shuttle software—the primary avionics software system, which [they] built from 1977 to 1980. The team applied IID in a series of 17 iterations over 31 months, averaging around eight weeks per iteration. Their motivation for avoiding the waterfall life cycle was that the shuttle program’s requirements changed during the software development process."[4]

Some organizations, such as the US Department of Defense, have a preference for iterative methodologies, starting with MIL-STD-498 "clearly encouraging evolutionary acquisition and IID".

The DoD Instruction 5000.2 released in 2000 stated a clear preference for IID:

There are two approaches, evolutionary and single step [waterfall], to full capability. An evolutionary approach is preferred. … [In this] approach, the ultimate capability delivered to the user is divided into two or more blocks, with increasing increments of capability...software development shall follow an iterative spiral development process in which continually expanding software versions are based on learning from earlier development. It can also be done in phases.

Recent revisions to DoDI 5000.02 no longer refer to "spiral development," but do advocate the general approach as a baseline for software-intensive development/procurement programs.[5] In addition, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) also employs an iterative and incremental developmental approach to its programming cycle to design, monitor, evaluate, learn and adapt international development projects with a project management approach that focuses on incorporating collaboration, learning, and adaptation strategies to iterate and adapt programming.[6]

Contrast with Waterfall development

The main cause of the software development projects failure is the choice of the model, so should be made with a great care.[7]

For example, the Waterfall development paradigm completes the project-wide work-products of each discipline in one step before moving on to the next discipline in a succeeding step. Business value is delivered all at once, and only at the very end of the project, whereas backtracking is possible in an iterative approach. Comparing the two approaches, some patterns begin to emerge:

- User involvement: In the waterfall model, the user is involved in two stages of the model, i.e. requirements and acceptance testing, and possibly creation of user education material. Whereas in the incremental model, the client is involved at each and every stage.

- Variability: The software is delivered to the user only after the build stage of the life cycle is completed, for user acceptance testing. On the other hand, every increment is delivered to the user and after the approval of user, the developer is allowed to move towards the next module.

- Human resources: In the incremental model fewer staff are potentially required as compared to the waterfall model.

- Time limitation: An operational product is delivered after months while in the incremental model the product is given to the user within a few weeks.

- Project size: Waterfall model is unsuitable for small projects while the incremental model is suitable for small, as well as large projects.

Implementation guidelines

Guidelines that drive software implementation and analysis include:

- Any difficulty in design, coding and testing a modification should signal the need for redesign or re-coding.

- Modifications should fit easily into isolated and easy-to-find modules. If they do not, some redesign is possibly needed.

- Modifications to tables should be especially easy to make. If any table modification is not quickly and easily done, redesign is indicated.

- Modifications should become easier to make as the iterations progress. If they are not, there is a basic problem such as a design flaw or a proliferation of patches.

- Patches should normally be allowed to exist for only one or two iterations. Patches may be necessary to avoid redesigning during an implementation phase.

- The existing implementation should be analyzed frequently to determine how well it measures up to project goals.

- Program analysis facilities should be used whenever available to aid in the analysis of partial implementations.

- User reaction should be solicited and analyzed for indications of deficiencies in the current implementation.

Use in hardware and embedded systems

While the term iterative and incremental development got started in the software industry, many hardware and embedded software development efforts are using iterative and incremental techniques.

Examples of this may be seen in a number of industries. One sector that has recently been substantially affected by this shift of thinking has been the space launch industry, with substantial new competitive forces at work brought about by faster and more extensive technology innovation brought to bear by the formation of private companies pursuing space launch. These companies, such as SpaceX[8] and Rocket Lab,[9] are now both providing commercial orbital launch services in the past decade, something that only six nations had done prior to a decade[10] ago. New innovation in technology development approaches, pricing, and service offerings—including the ability that has existed only since 2016 to fly to space on a previously flown (reusable) booster stage—further decreasing the price of obtaining access to space.[11][8]

SpaceX has been explicit about its effort to bring iterative design practices into the space industry, and uses the technique on spacecraft, launch vehicles, electronics and avionics, and operational flight hardware operations.[12]

As the industry has begun to change, other launch competitors are beginning to change their long-term development practices with government agencies as well. For example, the large US launch service provider United Launch Alliance (ULA) began in 2015 a decade-long project to restructure its launch business—reducing two launch vehicles to one—using an iterative and incremental approach to get to a partially-reusable and much lower-cost launch system over the next decade.[13]

See also

- Adaptive management

- Agile software development

- Continuous integration

- DevOps § Incremental adoption

- Dynamic systems development method

- Goal-Driven Software Development Process

- Interaction design

- Kaizen

- Microsoft Solutions Framework

- Object-oriented analysis and design

- OpenUP/Basic

- PDCA

- Rapid application development

- Release early, release often

Notes

- ↑ Larman, Craig (June 2003). "Iterative and Incremental Development: A Brief History" (PDF). Computer. 36 (6): 47–56. doi:10.1109/MC.2003.1204375. ISSN 0018-9162. S2CID 9240477.

We were doing incremental development as early as 1957, in Los Angeles, under the direction of Bernie Dimsdale [at IBM's ServiceBureau Corporation]. He was a colleague of John von Neumann, so perhaps he learned it there, or assumed it as totally natural. I do remember Herb Jacobs (primarily, though we all participated) developing a large simulation for Motorola, where the technique used was, as far as I can tell ...'

- ↑ DOD-STD-2167 Defense Systems Software Development (04 JUN 1985) on everyspec.com

- ↑ Farcic, Viktor (January 21, 2014). "Software Development Models: Iterative and Incremental Development". Technology Conversations.

- 1 2 Iterative and Incremental Development: A Brief History, Craig Larman and Victor Basili, IEEE Computer, June 2003

- ↑ Kendall, Frank; Gilmore, J. Michael; Halvorsen, Terry (2017-02-02). "Operation of the Defense Acquisition System" (PDF). DoD Issuances. Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics. pp. 12–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ↑ USAID. "ADS Chapter 201 Program Cycle Operational Policy" Archived 2019-10-23 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 19, 2017

- ↑ "Difference between Waterfall and Incremental Model". May 19, 2016.

- 1 2 Belfiore, Michael (9 December 2013). "The Rocketeer". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ↑ "Exclusive Inside Look at Rocket Lab's Previously-secret new Mega Factory!". Everyday Astronaut. 11 October 2018. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ↑

Clark, Stephen (28 September 2008). "Sweet Success at Last for Falcon 1 Rocket". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

the first privately developed liquid-fueled rocket to successfully reach orbit.

- ↑

Berger, Eric (2018-06-25). "Russia's Proton rocket, which predates Apollo, will finally stop flying Technical problems, rise of SpaceX are contributing factors". arsTechica. Retrieved 2018-06-26.

the rapid rise of low-cost alternatives such as SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket, have caused the number of Proton launches in a given year to dwindle from eight or so to just one or two.

- ↑

Fernholz, Tim (21 October 2014). "What it took for Elon Musk's SpaceX to disrupt Boeing, leapfrog NASA, and become a serious space company". Quartz. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

But SpaceX always thought of itself as a tech firm, and its clashes with NASA often took a form computer developers—or anyone familiar with the troubled roll-out of healthcare.gov—would recognize as generational. SpaceX followed an iterative design process, continually improving prototypes in response to testing. Traditional product management calls for a robust plan executed to completion, a recipe for cost overruns.

- ↑

Gruss, Mike (2015-04-24). "Evolution of a Plan : ULA Execs Spell Out Logic Behind Vulcan Design Choices". Space News. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

ULA's April 13 announcement that it would develop a rocket dubbed Vulcan using an incremental approach whose first iteration essentially is an Atlas 5 outfitted with a new first stage.

References

- Dr. Alistair Cockburn (May 2008). "Using Both Incremental and Iterative Development" (PDF). STSC CrossTalk. USAF Software Technology Support Center. 21 (5): 27–30. ISSN 2160-1593. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-26. Retrieved 2011-07-20.

- Craig Larman, Victor R. Basili (June 2003). "Iterative and Incremental Development: A Brief History" (PDF). IEEE Computer. IEEE Computer Society. 36 (6): 47–56. doi:10.1109/MC.2003.1204375. ISSN 0018-9162. S2CID 9240477. Retrieved 2009-01-10.