| Infarction | |

|---|---|

| |

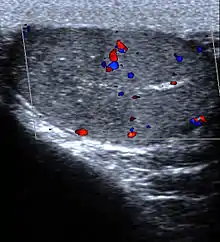

| Micrograph of a pulmonary infarct (right of image) beside relatively normal lung (left of image). H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Pathology |

Infarction is tissue death (necrosis) due to inadequate blood supply to the affected area. It may be caused by artery blockages, rupture, mechanical compression, or vasoconstriction.[1] The resulting lesion is referred to as an infarct[2][3] (from the Latin infarctus, "stuffed into").[4]

Causes

Infarction occurs as a result of prolonged ischemia, which is the insufficient supply of oxygen and nutrition to an area of tissue due to a disruption in blood supply. The blood vessel supplying the affected area of tissue may be blocked due to an obstruction in the vessel (e.g., an arterial embolus, thrombus, or atherosclerotic plaque), compressed by something outside of the vessel causing it to narrow (e.g., tumor, volvulus, or hernia), ruptured by trauma causing a loss of blood pressure downstream of the rupture, or vasoconstricted, which is the narrowing of the blood vessel by contraction of the muscle wall rather than an external force (e.g., cocaine vasoconstriction leading to myocardial infarction).[5]

Hypertension and atherosclerosis are risk factors for both atherosclerotic plaques and thromboembolism. In atherosclerotic formations, a plaque develops under a fibrous cap. When the fibrous cap is degraded by metalloproteinases released from macrophages or by intravascular shear force from blood flow, subendothelial thrombogenic material (extracellular matrix) is exposed to circulating platelets and thrombus formation occurs on the vessel wall occluding blood flow. Occasionally, the plaque may rupture and form an embolus which travels with the blood-flow downstream to where the vessel narrows and eventually clogs the vessel lumen.

Classification

By histopathology

Infarctions are divided into two types according to the amount of blood present:

- White infarctions (anemic infarcts) affect solid organs such as the spleen, heart and kidneys wherein the solidity of the tissue substantially limits the amount of nutrients (blood/oxygen/glucose/fuel) that can flow into the area of ischaemic necrosis. Similar occlusion to blood flow and consequent necrosis can occur as a result of severe vasoconstriction as illustrated in severe Raynaud's phenomenon that can lead to irreversible gangrene.

- Red infarctions (hemorrhagic infarcts) generally affect the lungs or other loose organs (testis, ovary, small intestines). The occlusion consists more of red blood cells and fibrin strands. Characteristics of red infarcts include:

- occlusion of a vein

- loose tissues that allow blood to collect in the infarcted zone

- tissues with a dual circulatory system (lung, small intestines)

- tissues previously congested from sluggish venous outflow

- reperfusion (injury)[6] of previously ischemic tissue that is associated with reperfusion-related diseases,[7] such as myocardial infarction, stroke (cerebral infarction), shock-resuscitation, replantation surgery, frostbite, burns, and organ transplantation.

By localization

- Heart: Myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, is an infarction of the heart, causing some heart cells to die. This is most commonly due to occlusion (blockage) of a coronary artery following the rupture of a vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque, which is an unstable collection of lipids (fatty acids) and white blood cells (especially macrophages) in the wall of an artery. The resulting ischemia (restriction in blood supply) and oxygen shortage, if left untreated for a sufficient period of time, can cause damage or kill heart muscle tissue (myocardium).

- Brain: Cerebral infarction is the ischemic kind of stroke due to a disturbance in the blood vessels supplying blood to the brain. It can be atherothrombotic or embolic.[8] Stroke caused by cerebral infarction should be distinguished from two other kinds of stroke: cerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebral infarctions vary in their severity with one third of the cases resulting in death. In response to ischemia, the brain degenerates by the process of liquefactive necrosis.[9]

- Lung: Pulmonary infarction or lung infarction

- Spleen: Splenic infarction occurs when the splenic artery or one of its branches are occluded, for example by a blood clot. Although it can occur asymptomatically, the typical symptom is severe pain in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen, sometimes radiating to the left shoulder. Fever and chills develop in some cases.[10] It has to be differentiated from other causes of acute abdomen.

- Limb: Limb infarction is an infarction of an arm or leg. Causes include arterial embolisms and skeletal muscle infarction as a rare complication of long standing, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus.[11] A major presentation is painful thigh or leg swelling.[11]

- Bone: Infarction of bone results in avascular necrosis. Without blood, the bone tissue dies and the bone collapses.[12] If avascular necrosis involves the bones of a joint, it often leads to destruction of the joint articular surfaces (see osteochondritis dissecans).

- Testicle: an infarction of a testicle is commonly caused by testicular torsion and may require removal of the affected testicle(s) if not undone by surgery quickly enough.[13]

- Eye: an infarction can occur to the central retinal artery which supplies the retina causing sudden visual loss.

- Bowel: Bowel infarction is generally caused by mesenteric ischemia due to blockages in the arteries or veins that supply the bowel.

Associated diseases

Diseases commonly associated with infarctions include:

- Peripheral artery occlusive disease (the most severe form of which is gangrene)

- Antiphospholipid syndrome

- Sepsis

- Giant-cell arteritis (GCA)

- Hernia

- Volvulus

- Sickle-cell disease

References

- ↑ "Definition of Infarction". MedicineNet. WebMD. April 27, 2011. Archived from the original on January 23, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ↑ "infarct". TheFreeDictionary.com. Citing:

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Updated in 2009.

- The American Heritage Science Dictionary 2005 by Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ↑ infract. CollinsDictionary.com. Collins English Dictionary – Complete & Unabridged 11th Edition. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ↑ "Infarct | Origin and meaning of infarct by Online Etymology Dictionary".

- ↑ "Infarction - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- ↑ Sekido, Nobuaki; Mukaida, Naofumi; Harada, Akihisa; Nakanishi, Isao; Watanabe, Yoh; Matsushima, Kouji (1993). "Prevention of lung reperfusion injury in rabbits by a monoclonal antibody against interleukin-8". Nature. 365 (6447): 654–7. Bibcode:1993Natur.365..654S. doi:10.1038/365654a0. PMID 8413628. S2CID 4282441.

- ↑ Sands, Howard; Tuma, Ronald F (1999). "LEX 032: a novel recombinant human protein for the treatment of ischaemic reperfusion injury". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 8 (11): 1907–1916. doi:10.1517/13543784.8.11.1907. PMID 11139833.

- ↑ Ropper, Allan H.; Adams, Raymond Delacy; Brown, Robert F.; Victor, Maurice (2005). Adams and Victor's principles of neurology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. Division. pp. 686–704. ISBN 0-07-141620-X.

- ↑ Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. Vinay Kumar, Abul K. Abbas, Jon C. Aster, James A. Perkins (Ninth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. 2015. ISBN 978-1-4557-2613-4. OCLC 879416939.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Nores, M; Phillips, EH; Morgenstern, L; Hiatt, JR (1998). "The clinical spectrum of splenic infarction". The American Surgeon. 64 (2): 182–8. PMID 9486895.

- 1 2 Grigoriadis, E; Fam, AG; Starok, M; Ang, LC (2000). "Skeletal muscle infarction in diabetes mellitus". The Journal of Rheumatology. 27 (4): 1063–8. PMID 10782838.

- ↑ Digiovanni, CW; Patel, A; Calfee, R; Nickisch, F (2007). "Osteonecrosis in the foot". The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 15 (4): 208–17. doi:10.5435/00124635-200704000-00004. PMID 17426292. S2CID 31296534.

- ↑ "Testicular torsion - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2021-08-10.

External links

![]() Media related to Infarction at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Infarction at Wikimedia Commons

![]() The dictionary definition of infarction at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of infarction at Wiktionary