| Interatherium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of Interatherium rodens in the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | †Notoungulata |

| Family: | †Interatheriidae |

| Subfamily: | †Interatheriinae |

| Genus: | †Interatherium Ameghino 1887 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

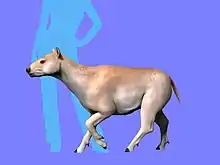

Interatherium is an extinct genus of interatheriid notoungulate from the Early to Middle Miocene (Colhuehuapian-Mayoan). Fossils have been found in the Santa Cruz, Collón Curá and Sarmiento Formations in Argentina.[1]

Description

This animal, of the size similar to that of today's American Mink (it was about 40 centimeters long excluding the tail), was equipped with a rather unusual morphology if related to that of its closest relatives. Contrary to shapes like Protypotherium, Interatherium possessed short and robust legs, and a long body and similar to that of a weasel. The front legs were equipped with four fingers. The ointment phalanges were compressed laterally, and some of these were divided.

The Interatherium skull was equally aberrant: it was in fact much more compact than that of other archaic types, and the muzzle was as if it had been crushed. The jaw, in particular, was very deep and tall, protruded backwards and owned considerable notches for the insertion of powerful masses masses (one of the main muscles capable of chewing in mammals). The Masseter muscle was anchored to a large bony flange placed in the lower part of the jaw, known as the descending process. This process is greatly reduced in related interatheres: Interatherium's well developed process was superficially similar to the ones seen in glyptodonts, a taxon of giant armadillos. Like the other interactors, Interatherium possessed a complete teeth, including 44 teeth, but differ in having a diastema between the incisors and premolars. The space was accentuated by the dimensions of the last incisive and the canine, so small as to be absent in some specimens.[2][3]

Classification

Interatherium was described for the first time in 1887 by Florentino Ameghino, on the basis of fossil remains found in the province of Santa Cruz, Argentina, in strata dating to the lower Miocene.[4] The type species is Interatherium rodens, which was named on the basis of a right maxilla that was first collected by Francisco P. Moreno in 1876-77. Several other species were described by Ameghino in 1894 (I. anguliferum, I. brevifrons, I. dentatum, I. interruptum, I. rodens, I. supernum, I. excavatus),[5] many of which were then considered synonyms of I. rodens, though many of their holotypes have been lost.[2][3]

Interatherium is the eponymous genus of the Interatheriidae family, a family that includes numerous medium-sized species from the Miocene of South America; Interatherium was most closely related to another Interathere from Santa Cruz, Cochilius.[3]

Paleobiology

Due to the short legs and the elongated body, some paleontologists believe that Interatherium may have been an animal that lived in underground dens, but the legs do not show particular adaptations to digging. It was certainly a herbivorous animal that fed on leaves, grass and vegetation that grew at the ground level, perhaps close to bodies of water.[6]

References

- ↑ Interatherium at Fossilworks.org

- 1 2 Fernández, M., Fernicola, J. C., & Cerdeño Serrano, M. E. (2019). On the type materials of the genera Interatherium Ameghino, 1887 and Icochilus Ameghino, 1889 (Interatheriidae, Notoungulata, Mammalia) from early Miocene of the Santa Cruz Province, Argentina.

- 1 2 3 Fernández, M. (2015). Revisión taxonómica de Interatherium Ameghino 1887 e Icochilus Ameghino 1889 (Interatheriidae, Notoungulata) de la Edad Mamífero Santacrucense (Mioceno Temprano) de la Provincia de Santa Cruz, Argentina. Luján: Departamento de Ciencias Básicas, Universidad Nacional de Luján.

- ↑ Ameghino, F. (1887). Enumeración sistemática de las especies de mamíferos fósiles coleccionados por Carlos Ameghino en los terrenos eocenos de la Patagonia austral y depositados en el Museo de La Plata. Boletín del Museo de la Plata.

- ↑ Ameghino, F. (1894). Enumération synoptique des espèces de mammifères fossiles des formations éocènes de Patagonie. Imp. de PE Coni é hijos.

- ↑ Kramarz, A. G., Vucetich, M. G., Carlini, A. A., Ciancio, M. R., Alejandra, M., Abello, C. M. D., & Gelfo, J. N. (2010). 18 A new mammal fauna at the top of the Gran Barranca sequence and its biochronological significance. The paleontology of Gran Barranca: evolution and environmental change through the middle Cenozoic of Patagonia, 264.

.jpg.webp)