Mythology of the Haudenosaunee includes the creation stories and folktales of the Native Americans who formed the confederacy of the Five Nations, later the Six Nations (Iroquois) Historically, these stories were recorded in wampum and recited, only being written down later. In the written versions, the spellings of names differ due to transliteration and spelling variations in European languages that were not yet standardized. Variants of the stories exist, reflecting different localities and times.

Oral traditions

The Haudenosaunee have passed down their stories as a centuries-old oral tradition. Through these stories, listeners learn values, laws, and acceptable behaviors in their communities [1] For example, "Girl Who Was Not Satisfied" is a traditional story about a girl who runs off with a man for his looks.[2] The moral of the story is to judge people based on their character, not their looks. The story also teaches people the importance of valuing what they already have.

Haudenosaunee storytelling is also entertainment and a way to preserve culture. The stories reflect the Iroquois' perception and understanding of the world.[3] Traditionally, the stories were poetic and delivered in metaphors. However, translations often lose the expressive qualities which existed in the original language.[4]: 10 It is also possible that Christianity influenced the written mythologies.[5]

In 1923, historian Arthur C. Parker wrote, "There is an amazing lack of authentic material on Iroquois-folklore, though much of what arrogates this name itself has been written. The writers, however, have in general so glossed the native themes with poetic and literary interpretations that the material has shrunken in value and can scarcely be considered without many reservations."[6]

Each Haudenosaunee village had a Hage'ota or storyteller who was responsible for learning and memorizing the ganondas'hag or stories.[7] Traditionally, no stories were told during the summer months in accordance with the law of the dzögä́:ö’ (transl. Little People).[7] Violators were said to suffer an omen or great evils, such as a being stung on the lips by a bee or being strangled by a snake while sleeping.[7][4]: 17 The Haudenosaunee believed that telling the stories in summer would make the animals, plants, trees, and humans lazy, as work stops for a good story..[7]

Stories

Following are examples of Iroquois myths, as recorded by Harriet Maxwell Converse in 1908, Arthur C. Parker in 1923, and others.[4]

Creation

The Earth was a thought in the mind of Hawëni:yo’ (transl. He Who Governs or The Ruler), the ruler of a great island floating above the clouds.[8] The floating island is a place of calm where all needs are provided and there is no pain or death. The island's inhabitants hold council under a great apple tree.[lower-alpha 1]

Hawëni:yo’ says, "Let us make a new place where another people can grow. Under our council tree is a great sea of clouds which calls out for light." He orders the uprooting of the council tree and he looks through the hole, down into the depths. He tells Awëöha’i’ (Mohawk:Atsi’tsaká:ion)[lower-alpha 2] (transl. Sky Woman) to look down. Hearing the voice of the sea below calling, Hawëni:yo’ tells Awëöha’i’, who was pregnant, to bring it life. He wraps her in light and drops her down through the hole.

All the birds and animals who live in the great cloud sea are panicked. The Duck asks, "Where can it rest?" The Beaver replies, "Only the oeh-dah (transl. earth) from the bottom of our great sea can hold it. I will get some." The Beaver dives down but never returns. Then, the Duck tries, but its dead body floats to the surface. Many of the other birds and animals try and fail.

Finally, the Muskrat returns with some Oeh-dah in his paws. He says, "It's heavy. Who can support it?" The Turtle volunteers and the oeh-dah is placed on top of his shell. The birds fly up and carry Awëöha’i’ on their wings to the Turtle's back. This is how Hah-nu-nah, the Turtle, came to be the earth bearer. When he moves, the sea gets rough and the earth shakes.[4]

The Do-yo-da-no

Once brought to the surface, the oeh-dah from the sea floor grows and forms an island. Ata-en-sic (transl. Sky Woman) goes to the island, knowing her time to give birth is near. She hears two voices under her heart. One voice is calm and quiet, but the other is loud and angry. Her children are the Do-yo-da-no or the Twin Gods. The good twin, Hah-gweh-di-yu or Teharonhiakwako, is born in the normal way.[9] The evil twin, Hä-qweh-da-ět-gǎh or Sawiskera, forces his way out from under his mother's arm, killing her.[9][lower-alpha 3]

After the death of Ata-en-sic, the island is shrouded in gloom. Hah-gweh-di-yu shapes the sky and creates the Sun from his mother's face saying, "You shall rule here where your face will shine forever." However, Hä-qweh-da-ět-gǎh sets the great darkness in the west to drive down the Sun. Hah-gweh-di-yu then takes the Moon and stars, his sisters, from his mother's breast and places them to guard the night sky. He gives his mother's body to the earth, the Great Mother from whom all life came.

Ga-gaah, the Crow, comes from the sun land carrying a grain of corn in his ear. Hah-gweh-di-yu plants the corn above his mother's body and it becomes the first grain. Ga-gaah hovers over the corn fields, guarding them against harm and claiming his share.[4]

Aid by assistants or subordinate spirits such as the Huron spirit Ioskeha, Hah-gweh-di-yu creates the first people, heals disease, defeats demons, and gives the Iroquois many magical and ceremonial rituals. Another of his gifts is tobacco, a central part of the Iroquois religion. In contrast, Hä-qweh-da-ět-gǎh brings dangerous and destructive things to the world. Thus, the Do-yo-da-no creation myth is also about the behaviors and morals of people.[10]

Notes

- ↑ Parker says "The central tree in the heaven world was the apple." The apple tree was introduced to North America by European settlers. Elsewhere, Parker suggests that the story refers to the crab apple (wild apple).

- ↑ Parker says: "Ata'-en'sic...s the Huron name for the first mother, and not that of the (confederated) Iroquois, The Senecas usually give this character no name other than Ea-gen'-tci, literally old woman or ancient body. This name is not a personal one, however. Mrs. Converse has therefore substituted the Huronian personal name for the Iroquoian common name."

- ↑ Other versions of the story say that Ata-en-sic gave birth to a daughter. This daughter was impregnated by the wind and gives birth to twins. After her death giving birth, she leaves her sons in the care of Ata-en-sic.

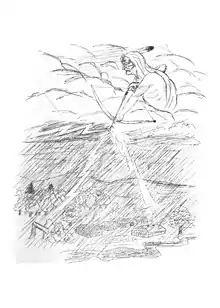

Hé-no

Iroquois mythology tells of Hé-no, the spirit of thunder who brings rain to nourish the crops. The Iroquois address Hé-no as Tisote (transl. Grandfather). He appears as a warrior, wearing on his head a magic feather that makes him invulnerable to the attacks of Hah-gweh-di-yu. On his back, he carries a basket filled with pieces of chert which he throws at evil spirits and witches.

Hé-no lives in a cave under Niagara Falls. At that time, a young girl lives above the falls and is engaged to marry a disagreeable old man. Rather than marry, she climbs into a canoe and heads down the river. The girl and the canoe are carried over the falls; the canoe is seen falling to destruction, but the girl disappears. Hé-no and his two assistants catch her in a blanket and take her to his cave. One of the assistants is taken with her beauty and marries her.

Later, Hé-no rescues her village from a huge serpent that was devastating it with diseases. He lures the serpent to a spot on Buffalo Creek where he strikes it with a thunderbolt. Fatally wounded, the serpent tries to escape to the safety of Lake Erie but dies before he gets away. His body floats downstream to the head of Niagara Falls, stretching nearly across the river and arching backward to form a dam. The dammed water breaks the rocks, and the snake's body falls onto the rocks below. This forms Horseshoe Falls but destroys Hé-no's home in the process.[8]

De-oh-há-ko

The Iroquois name De-oh-há-ko means Our Life or Our Supporters. Often called the Three Sisters, the De-oh-há-ko are the spirits of corn, beans, and squash. The sisters have the form of beautiful maidens. They are fond of each other and like to live near each other. This is an analogy to the three plants which are historically grown from the same mound.[8]

One day while O-na-tah, the spirit of the corn, is wandering alone, she is captured by Hä-qweh-da-ět-gǎh, the evil Twin God. Hä-qweh-da-ět-gǎh sends one of his monsters to devastate the fields, and the other sisters run away. Hä-qweh-da-ět-gǎh holds O-na-tah captive in darkness under the earth until a searching ray of sunlight reached the surface. Back on the Earth's surface, she weeps over the devastation to her fields and her abandonment by her sisters. She vows to never again leave her fields, which she guards alone, without her sisters.[4]

Jo-ga-oh

Iroquois myths tell of the dzögä́:ö’ (Jo-gä-oh) or the Little People. The dzögä́:ö’ are invisible nature spirits, similar to the fairies of European myth. They protect and guide the natural world and protect people from unseen hidden enemies. There are three tribes of dzögä́:ö’.

The first tribe is the Ga-hon-ga who inhabit rivers and rocks. They live in rocky caves beside streams and have great strength despite their small stature. The Ga-hon-ga enjoy feats of strength and enjoy inviting people to their habitations to compete in contests. They enjoy playing ball with rocks, tossing the rocks high in the air, so they are often called Stone Throwers.

The second tribe is the Gan-da-yah who protect and advise the fruits and grains. Throughout the growing season, the Gan-da-yah guards crops against disease and other pests. Their special gift is the strawberry plant; in the spring they loosen the earth so it can grow. They turn strawberry leaves toward the sun and guide their runners. When the strawberries ripen, the Honödí:ön (transl. Company of Faith Keepers) hold the spring festival with its nighttime dances of thanksgiving to the dzögä́:ö’. They sometimes visit the people in the form of a robin for good news, an owl for a warning, or a bat for an imminent life-and-death struggle. Believers in the Gan-da-yah say, "The most minute harmless insect or worm may be the bearer of important 'talk' from the 'Little People' and is not destroyed for the 'trail is broad enough for all'"..[4]

The third tribe of dzögä́:ö’ are the Oh-do-was, who inhabit the shadowy places under the earth. In this underworld, there are forests and animals, including a white buffalo. The Oh-do-was guard against poisonous snakes and creatures of death that try to escape from the underworld. Occasionally, the Oh-do-was emerge from the underworld at night and visit the world above where they hold festivals and dance in rings around trees. Afterward, grass will not grow in the ring.[4]: 101–107

Gǎ-oh

Iroquois myths tell of Gaoh, the personification of the wind. He is a giant and an "instrumentality through whom the Great Spirit moves the elements".[8] His home is in the far northern sky.[4][lower-alpha 1] He controls the four winds: north wind (Bear), west wind (Panther), east wind (Moose), and south wind (Fawn).[4]

The North Wind is personified by a bear spirit named Ya-o-gah. Ya-o-gah can destroy the world with his fiercely cold breath but is kept in check by Gǎ-oh. Ne-o-ga, the south wind, is as "gentle, and kind as the sunbeam". The West Wind, the panther Da-jo-ji, "can climb the high mountains, and tear down the forests...carry the whirlwind on [his] back, and toss the great sea waves high in the air, and snarl at the tempests". O-yan-do-ne, the east wind, blows his breath "to chill the young clouds as they float through the sky".

So-son-do-wah

According to Iroquois mythology, So-son-do-wah is a great hunter, known for stalking a supernatural elk. He is captured by Dawn, a goddess who needs him as a watchman. So-son-do-wah falls in love with the human woman Gendenwitha (transl. She Who Brings the Day, alternate spelling: Gendewitha). He tried to woo her with song. In spring, he sings as a bluebird, in summer as a blackbird, and in autumn as a hawk. The hawk tries to take Gendenwitha into the sky with him. However, Dawn ties So-son-do-wah to her doorpost. She changes Gendenwitha into the Morning Star, so the hunter can watch her all night but never be with her.

Flying Head

Iroquois mythology tells of the Flying Head (Mohawk Kanontsistóntie), a monster in the form of a giant disembodied head as tall as a man. It is covered with thick hair and has long black wings and long sharp claws. At night, the Flying Head comes to the homes of widows and orphans, beating its wings on the walls of the houses and issuing terrifying cries in an unknown language. A few days after the Flying Head visits, a death claims one of the family.[11] The Seneca name for the Flying Head is Takwánö'ë:yët, meaning whirlwind.

Djodi'kwado

According to Iroquois mythology, Djodi'kwado' is a horned serpent who inhabits the depths of rivers and lakes. He is capable of taking the form of a man and seducing young women. He is prominent in the tales "Thunder Destroys Horned Snake".[12] and "The Horned Serpent Runs Away with a Young Wife who is Rescued by the Thunderer".[13]: 218–222 In the latter, he appears as a helpful being, although his help is less than useful. Hé-no attacks and may have killed Djodi'kwado'.[13]: 223–227

Tuscarora legend

William Byrd II recorded a tradition of a former religious leader from the Tuscarora tribe, in his History of the Dividing Line Betwixt North Carolina and Virginia (1728), The Tuscarora are an Iroquoian-speaking tribe, historically settled in North Carolina, that migrated to the Iroquois Confederacy in New York because of warfare. According to Byrd:

[H]owever, their God, being unwilling to root them out for their crimes, did them the honour to send a Messenger from Heaven to instruct them, and set Them a perfect Example of Integrity and kind Behavior towards one another. But this holy Person, with all his Eloquence and Sanctity of Life, was able to make very little Reformation amongst them. Some few Old Men did listen a little to his Wholesome Advice, but all the Young fellows were quite incorrigible. They not only Neglected his Precepts, but derided and Evil Entreated his Person. At last, taking upon him to reprove some Young Rakes of the Conechta Clan very sharply for their impiety, they were so provok'd at the Freedom of his Rebukes, that they tied him to a Tree, and shot him with Arrows through the Heart. But their God took instant vengeance on all who had a hand in that Monstrous Act, by Lightning from Heaven, & has ever since visited their Nation with a continued Train of Calamities, nor will he ever leave off punishing, and wasting their people, till he shall have blotted every living Soul of them out of the World.[14]

The Three Brothers

This is an Iroquois sun myth about three brothers who tire of being on Earth and decide to chase the Sun into the sky. Two of the brothers succeed, with the third succeeding in spirit only. The Sun Spirit remakes and tests the two brothers, who stay in the realm of the sky for many years. They eventually miss their home and return, only to find that many years have passed. With everything they knew either changed or gone, they long to return to the realm of the sky. They return to the sky when they are struck by lightning, as earthly perils could not harm them.[15]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Parker says Gǎ-oh lives in the west.

References

- ↑ "The Boy Who Lived With the Bears". Indigenous People. Retrieved 2021-10-13.

- ↑ "Iroquois: The Girl Who Was Not Satisfied With Simple Things". Bedtime-Story For the Busy Business-Parent. Retrieved 2021-10-13.

- ↑ Wonderley, Anthony (2004). Oneida Iroquois Folklore, Myth, and History: New York Oral Narrative from the Notes of H. E. Allen and Others. Syracuse University Press. pp. xviii. ISBN 9780815608301.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Converse, Harriet Maxwell (Ya-ie-wa-no); Parker, Arthur Caswell (Ga-wa-so-wa-neh) (December 15, 1908). "Myths and Legends of the New York State Iroquois". Education Department Bulletin. University of the State of New York: 10–17. Retrieved Nov 9, 2014.

- ↑ Richter, Daniel K. (1985). "Iroquois versus Iroquois: Jesuit Missions and Christianity in Village Politics, 1642-1686". Ethnohistory. 32 (1): 1–16. doi:10.2307/482090. JSTOR 482090.

- ↑ Parker, Arthur Caswell (1923). Seneca Myths and Folk Tales. Buffalo, New York: Buffalo Historical Society. pp. xvii. Retrieved May 26, 2015 – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 Parker, Arthur Caswell (1923). Seneca Myths and Folk Tales. Buffalo, New York: Buffalo Historical Society. pp. xxv-xxvi. Retrieved May 26, 2015 via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 Morgan, Lewis Henry (1995). The League of the Iroquois. J G Press. pp. 141–174. ISBN 1-57215-124-2.

- 1 2 Louellyn White (2015). Free to Be Mohawk: Indigenous Education at the Akwesasne Freedom School. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780806153254.

- ↑ Gilan, Amir (2021-04-30), "'Let Those Important Primeval Deities Listen'", Gods and Mortals in Early Greek and Near Eastern Mythology, Cambridge University Press, pp. 19–36, doi:10.1017/9781108648028.003, ISBN 9781108648028, S2CID 233595010, retrieved 2021-10-13

- ↑ Canfield, William W. (1902). The Legends of the Iroquois: Told by "the Cornplanter". New York: A. Wessels Company. pp. 125–126. Retrieved Jan 27, 2016.

- ↑ "Thunder Destroys Horned Snake". Internet Sacred Text Archive. Retrieved Jan 2, 2020.

- 1 2 Parker, Arthur C. (1923). Seneca Myths and Folk Takes. Buffalo, New York: Buffalo Historical Society. Retrieved Jan 2, 2020.

- ↑ William Byrd II, History of the Dividing Line, entry for Nov. 12, 1728.

- ↑ Parker, Arthur C. (1910-01-01). "Iroquois Sun Myths". The Journal of American Folklore. 23 (90): 473–478. doi:10.2307/534334. JSTOR 534334.

External links

| Mythology |

|---|